Which Was Singapore's First Courthouse?

Singapore’s former Parliament building, known today as The Arts House, was used as a courthouse from 1828 to 1939. Prior to that, legal hearings were held in at least three other venues.

By Kevin Y.L. Tan

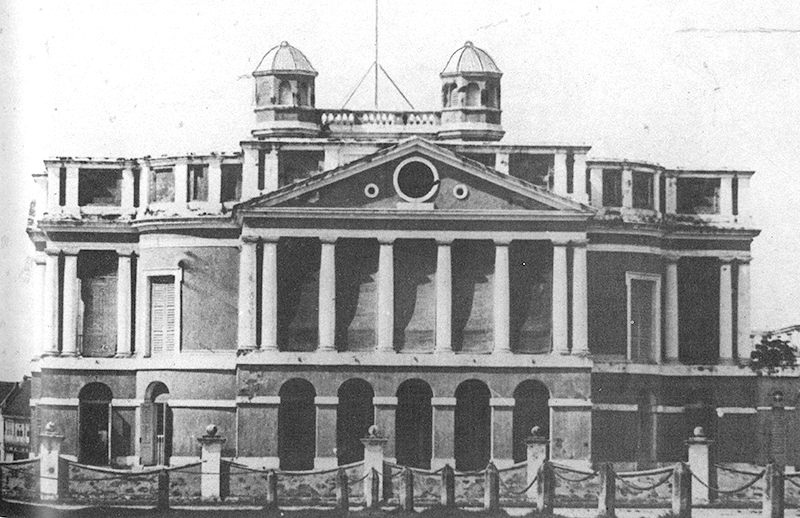

Official records establish that Singapore’s first courthouse was located in a building at Empress Place, off High Street, known today as The Arts House. While it was built for Scottish merchant John Argyle Maxwell in 1827, he never used it for his residence, and the building was leased to the government as a courthouse. On 22 May 1828, it was used for the first-ever session of the Court of Judicature of the Prince of Wales Island (Penang), Singapore and Melaka held in Singapore.

In this sense, it would be correct to say that Maxwell’s House was Singapore’s first courthouse.

However, this would imply that no courts had sat in Singapore between the time of Stamford Raffles’ arrival in January 1819 and May 1828, a period of close to 10 years. This is certainly not the case. In fact, the building at Empress Place is the fourth building in Singapore to have been used as a courthouse.

British Jurisdiction in Early Singapore

After Stamford Raffles and William Farquhar arrived in Singapore in January 1819 and determined that the Dutch had no presence on the island, the British East India Company (EIC) signed a Treaty of Friendship and Alliance (the First Charter of Justice Singapore) with Sultan Hussein Shah and Temenggong Abdul Rahman on 6 February 1819.

Under the treaty, the EIC was given “full permission” to “establish a factory or factories at Singapore, or on any other part” thereof.1 Although the treaty did not set out the territory to be governed by the new settlement, a document titled “Arrangements Made for the Government of Singapore” dated 25 June 1819 stipulated that the British would control the area stretching from Tanjong Malang on the west to Tanjong Katang (Katong) in the east, “and on the land side, as far as the range of cannon shot, all round from the factory”.2

At the time, Singapore’s population was small, with possibly between 400 and 1,000 persons on the island, the bulk of whom lived on its southern shore, near the mouth of the modern-day Singapore River and Rochor Canal. Most of the inhabitants were the Orang Laut (sea people) as well as the Malays and followers of the Temenggong, whose compound was on the bank of the Singapore River, the site of the Asian Civilisations Museum today. We have no evidence as to what law was administered by the Temenggong, but it was most probably a mix of Islamic syariah law and local Malay custom, or adat.

The new settlement occupied a small jurisdiction, stretching roughly 8 km along the southern coast of Singapore island and 1.2 km inland from the southern shore.3 Article 6 of the treaty provided that “all persons belonging to the English factory… or who shall hereafter desire to place themselves under the protection of its flag, shall be duly registered and considered as subject to the British authority”.4 As to the law applicable to the “native population”, the “mode of administering justice… shall be subject to future discussion and arrangement between the contracting parties, as this will necessarily, in a great measure, depend on the laws and usages of the various tribes who may be expected to settle in the vicinity of the English factory”, as spelt out in Article 7.5 The port of Singapore was, by Article 8, placed “under the immediate protection and subject to the regulations of the British Authorities”.6

At this point, the Treaty of Friendship and Alliance established that insofar as the British factory was concerned, the British would have jurisdiction provided the subject either “belonged” to the factory (such as employees of the EIC), or those who voluntarily submitted to British jurisdiction (most probably European and other merchants trading on the island within the factory zone). Subjects under the sovereign control of the Sultan and Temenggong were not subject to this jurisdiction, and neither were the rest of the “native population”. No further arrangements were made for the administration of justice upon Raffles’ departure on 7 February 1819, the day after he concluded the treaty.

The Rooma Bechara

On 26 June 1819, Raffles and Farquhar signed a further agreement with the Sultan and Temenggong on arrangements to be made for the “Government of Singapore”.7 Responsibility for governing the British port was conferred on a triumvirate consisting of the Sultan, the Temenggong and the Resident, while those persons residing within the British port – but “not within the campongs of the Sultan and Tumungong” – would be under the “control of the Resident”.8 Of the seven articles in this second agreement, four of them dealt specifically with the administration of justice:9

Article 3

All cases which may occur, requiring Council in his Settlement, they shall, in the first instance, be conferred and deliberated upon by the three aforesaid, and, when they shall have been decided upon, they shall be made known to the inhabitants, either by beat of gong or by proclamation.

Article 4

Every Monday morning, at 10 o’clock, the Sultan, the Tumungong, and the Resident shall meet at the Rooma Bechara; but should either of the two former be incapable of attending, they may send a Deputy there.

Article 5

Every Captain, or head of a caste, and all Panghulus of campongs and villages, shall attend at the Room Bechara, and make a report or statement of such occurrences as may have taken place in the Settlement; and represent any grievance or complaint that they may have to bring before the Council for its considerations on each Monday.

Article 6

If the Captains, or heads of castes, or the Panghulus of campongs, do not act justly towards their constituents, they are permitted to come and state their grievances themselves to the Resident at the Rooma Bechara, who is hereby authorized to examine and decide thereon.

Article 4 established the Rooma Bechara (“Rumah Bicara” in its modern-day spelling) meaning Courthouse or Council House. We have no records to show when this Rooma Bechara first came into operation but evidence suggests that it was quite soon after the making of this agreement. This was because Farquhar – whom Raffles appointed British Resident of the settlement – had written to Raffles in November 1819 suggesting the engagement of an assistant to help with the judicial process. Farquhar proposed that:

“… the Court or Bechara, consisting of the Sultan, Temenggong & British Resident, which assembles at present usually every Monday morning to hear and decide in whatever courses or complaints may be brought before it, be in future, assisted by an executive officer or agent of the Court, to be a British gentleman, appointed & paid by Government, whose duty it will be to take examination in conjunction with the Captains or Native Chiefs on the first instance, into all complaints, civil or criminal, which may be brought before him, & to present a written record in English & Malays to the Court or Bechara, at which, all parties & witnesses must attend to undergo such further examination, as may be deemed necessary; a Native Writer & a few Peons to be assigned to the Agent of the Court of Bechara for the police duties of the Settlement.”10

Farquhar recommended appointing David S. Napier to the post of Assistant or Agent in the Police Department at a monthly salary of 150 Spanish dollars to assist in the court’s work. So while we have no record of the kinds of cases brought before the Rooma Bechara each Monday morning, there would have been sufficient work to warrant such a request from Farquhar. What Farquhar had proposed was a more formalised mode of recording witness accounts and cross-examinations by appointing Napier as something akin to a registrar of the court. Raffles, however, turned down Farquhar’s request and ordered that “all the duties of police” and the court be “conducted by the Resident himself until further orders”.11

Where was this Rooma Bechara located? From the records, we know that the Bechara met at what was then known as “the Residency” – a cluster of wood and attap “bungalows and outhouses” that Farquhar erected and kept “in repair” for his accommodation as Resident, and which were also used as a treasury, public office, courthouse and church.12

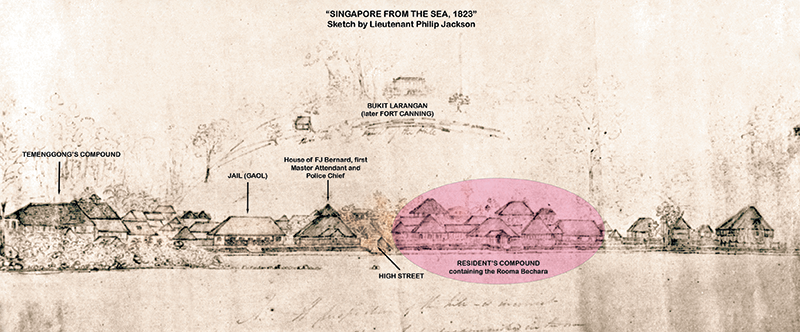

This cluster of buildings was located at what is now the junction of High Street and St Andrew’s Road, where the old Supreme Court building (it is today part of the National Gallery Singapore, along with the former City Hall building) stands.13 The structures making up the Residency can be seen in the shaded portion of the well-known sketch “Singapore from the Sea, 1823” by Assistant Engineer and Surveyor of Public Lands Lieutenant Philip Jackson. It is, however, impossible to identify exactly which of these buildings was used as the Rooma Bechara, but this would have been the location of Singapore’s very first courthouse.

The Residency was, from 1819 to 1823, the focal point of the settlement, and visitors would typically land at the Resident’s Steps and then proceed to the Residency compound. The Resident appointed “Captains” or “Chiefs” – prominent and respected community leaders – for the various ethnic groups and entrusted each with the preservation of peace and settlement of minor disputes.14 In 1820, there was a captain for the Chinese (who was assisted by two deputies), and one captain each for the Bugis, Malay and Chulia populations.15

The Second Charter of Justice in Singapore

Following the signing of the Anglo-Dutch Treaty on 17 March 1824, Singapore’s second Resident, John Crawfurd, succeeded in purchasing outright the whole of Singapore island from the Sultan and the Temenggong. This meant that the British now had jurisdiction over the entire island, and not just the settlement. For all intents and purposes, the Rooma Bechara ceased to exist since there was no further need to involve the Malay rulers in the administration of justice.

In its place, Crawfurd established the Resident’s Court, which fulfilled the same function as the old Rooma Bechara, except that he presided every Monday as sole adjudicator. Later, most probably in 1826, the Resident’s house and the Resident’s Court and Police Offices were relocated across the Singapore River to what was then known as the Government Godowns Nos. 2 and 3 at Commercial Square. These premises had been appropriated for use as the Resident’s Court and Police Offices, and Secretary and Master Attendant Offices.16 These were not purpose-built administrative buildings but temporary premises, which were sturdier than the old Residency buildings that Farquhar had erected. These buildings, temporary though they were, would have housed Singapore’s second courthouse.

With Singapore’s sovereignty now in British hands, the EIC proceeded to establish a new Charter of Justice that would extend the jurisdiction of the Court of Judicature of the Prince of Wales Island (Penang) to both Singapore and Melaka. There were delays in the promulgation of the Charter (dated 27 November 1826), which did not arrive in Penang (then the headquarters of the Straits Settlements) until August 1827. News of the arrival of the Second Charter reached Singapore about the same time it did Penang, and the arrival of the Recorder (as judges were then known) was awaited with great anticipation.

In the meantime, the Resident Councillor – first John Prince and then Kenneth Murchison – continued to run the Resident’s Court. Preparations began in Singapore in anticipation of the opening of the new Court of Judicature. One of the most urgent issues was finding a suitable building to house the court, especially since the Government Godowns at Commercial Square were wholly unsuited for use as the new court. The Singapore authorities set about scouting for a suitable building that would be large enough to accommodate the court and rooms for the Recorder while he was in the settlement.

In May 1827, the authorities identified a large house belonging to John Argyle Maxwell, which was still under construction.17 The inspector-general was tasked to inspect the building to determine if it might be adapted for use as a Government House, a Courthouse and Recorder’s Chambers. The elegant Palladian building, which came to be known as Maxwell’s House, had been designed by George Drumgold (G.D.) Coleman and was scheduled for completion in September 1827. Writing to the Recorder, John Claridge, in Penang in January 1828, Governor of the Straits Settlements Robert Fullerton apprised him on the preparations for judicial accommodations in Singapore:

“In respect to arrangements at Singapore and Malacca for the accommodation of the Recorder and Court, it may be necessary to mention that the former being a place recently established not one of the regular buildings usually maintained at a British Settlement, Government House, Court House, Jail, Church etc have yet been erected, temporary means were of necessity resorted to, and a large house was engaged for, to be ready last November, the lower part of which was every way adapted for the Court, the upper for Chambers, and a place of residence for the Recorder; no intimation has yet been received officially of its being actually ready, but as orders have been sent to have it furnished, and placed on a proper footing, we conclude all will be found in due state of preparation.”18

A note in the Resident Councillor’s diary dated 19 December 1827 suggests that there were delays in the construction of Maxwell’s House, and that Coleman had assured the authorities that it would be completed in less than three months. However, it was expected that having heard its first sessions in Penang in December 1827, the Court of Judicature would travel on circuit to Singapore in January 1828. This meant that Maxwell’s House would not be ready for use as a courthouse. An alternative would have to be found.

John Francis, proprietor of the Singapore Hotel, saw an opportunity and offered to lease his house to the authorities for use as a courthouse at 300 Sicca Rupees per month.19 The offer was left to the governor to decide. A month later, on 28 February 1828, it is recorded that the New Tavern (also run by Francis) at Commercial Square had been “engaged as a temporary Court house” and as “sundry furniture and records, connected with the Judicial Office” were “deposited therein”, the Commanding Officer of the Troops was requested to station a small military guard post there until further notice.20 In the meantime, the godown space beneath the Resident’s Office, which had hitherto served as a courthouse, was to be converted into a temporary jail for prisoners committed to stand trial.21 The New Tavern, another temporary location, thus operated as Singapore’s third courthouse, albeit, for a very short while.

By the time Fullerton and his retinue arrived in Singapore on 8 May 1828, Maxwell’s House was already completed. Fullerton was greeted by the customary salutes. Sitting with Kenneth Murchison, the Resident Councillor, Fullerton opened the first criminal hearing (known as the session of Oyer and Terminer and Gaol Delivery), and presided over the first-ever Court of Judicature of the Prince of Wales Island (Penang), Singapore and Melaka in Singapore on 22 May 1828.22 Notice of the first General Quarter Session of the court, to be held in Singapore on 2 June 1828, was published in the local newspapers.23

Fullerton and Murchison completed the first session, hearing 27 indictments brought by the Grand Jury. Six accused were found guilty of murder, one for manslaughter, and the rest for assault and offences against property. Two persons were sentenced to death, while two other persons indicted for piracy had to be released for the court’s want of admiralty jurisdiction.24

After the Singapore sessions ended on 5 June 1828, Fullerton proceeded to Melaka where he opened the Assizes and held a session of Oyer and Terminer and Gaol Delivery for the first time on 16 June 1828, sitting alongside Samuel Garling, the Resident Councillor of Melaka.25 Fullerton was back in Penang by the end of June, just in time for the next local sitting of the court.

The Court of Oyer and Terminer and Gaol Delivery was not to convene again in Singapore or Melaka during the rest of 1828, although Quarter Sessions were held in Singapore on 2 September 182826 and 2 December27 1828.

In view of history, it may said that while Maxwell’s House was the first “official” courthouse, the Court of Judicature having sat for the very first time in that building in May 1828, it was actually the fourth building in Singapore to have been used as one.

Maxwell’s House was used as the Court of Judicature and other government offices until 1839 when a separate single-storey building was erected on the side of the original building for the sole use of the court. Unfortunately, it was too noisy, being close to the adjoining shipbuilding yard. However, nothing was done until 1864 when a new building was built nearby to house the court. This building, which was completed in 1867, forms the oldest section of the Asian Civilisations Museum today, nearest to Cavenagh Bridge. This was Singapore’s first purpose-built courthouse.

In the meantime, Maxwell’s House was becoming overcrowded by the various government departments contained within. As a result, it was decided that a swap be made. The court, which had been reconstituted as the Supreme Court of the Straits Settlements in 1867, returned to Maxwell’s House as the sole occupant in 1872 while the government departments moved to the former court building.

In 1901, Maxwell’s House was completely renovated and extended to its current dimensions to accommodate an ever-enlarging court establishment. The Supreme Court remained in Maxwell’s House until 1939 when it moved to the newly built Supreme Court building at the junction of St Andrew’s Road and High Street.

After the Supreme Court moved out, Maxwell’s House was used as a government storehouse and as government offices before being renovated in the mid-1950s to become the Legislative Assembly House.

From 1965 to 1999, it was known as Parliament House until Parliament moved into its current location at 1 Parliament Place. Maxwell’s house was reopened in 2004 as an arts venue known as The Arts House. Both the main building and annex were gazetted as national monuments in 1992.

The Supreme Court, meanwhile, occupied the building at the junction of St Andrew’s Road and High Street until 2005 when it moved to its current location at 1 Supreme Court Lane. The old Supreme Court building, together with the former City Hall building next to it, now house National Gallery Singapore.

REFERENCES

Chong, Vince, “Old Parliament House, 4 Others Win Heritage Awards,” Straits Times, 13 October 2004, 9. (From Newslink via NLB’s eResources website)

“Dignified Pageantry at Opening of New Supreme Court,” Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, 4 August 1939, 9. (From NewspaperSG)

“Facelift for Oldest Building a Winner,” Straits Times, 13 October 2004, 2. (From Newslink via NLB’s eResources website)

Faizah Zakaria, “Supreme Court,” in Singapore Infopedia. National Library Board Singapore. Article published 2011.

Helmi Yusof, "PM Lee Unveils S$532m National Gallery," Business Times, 24 November 2015, 5. (From Newslink via NLB’s eResources website)

Makepeace, Walter, Gilbert E. Brooke and Roland St. John Braddell, eds., One Hundred Years of Singapore, vol. 1 (Singapore: Oxford University Press, 1991), 179–180. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSING 959.57 ONE-[HIS])

“Overview: About The Arts House,” Arts House Limited, accessed 6 February 2023, https://artshouselimited.sg/tah-about#section-id-1643460266223.

Tan, Clarissa, “A Supreme Makeover,” Business Times, 10 September 2010, 10. (From Newslink via NLB’s eResources website)

Dr Kevin Y.L. Tan is Adjunct Professor at the Faculty of Law, National University of Singapore, and Senior Fellow at the S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies, Nanyang Technological University. He specialises in constitutional and administrative law, Singapore legal history and international human rights. He has written and edited over 60 books on the law, history and politics of Singapore.

Dr Kevin Y.L. Tan is Adjunct Professor at the Faculty of Law, National University of Singapore, and Senior Fellow at the S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies, Nanyang Technological University. He specialises in constitutional and administrative law, Singapore legal history and international human rights. He has written and edited over 60 books on the law, history and politics of Singapore.NOTES

-

“Treaty of Friendship and Alliance concluded between the Honourable Sir Thomas Stamford Raffles Lieutenant Governor of Fort Marlborough and its Dependencies, Agent to the Most Noble Francis Marquess of Hastings Governor General of India, etc, for the Honorable English East India Company on the one part and their Highnesses Sultan Hussein Mahummud Shah Sultan of Johore and Datoo Tummungung Sree Maharajah Abdul Raman Chief of Singapoora and its Dependencies; n the other part”. See Charles Burton Buckley, An Anecdotal History of Old Times in Singapore, vol. 1 (Singapore: Fraser and Neave, 1902), 38. (From BookSG) ↩

-

“Arrangements Made for the Government of Singapore, in June 1819” as reproduced in Thomas St John Braddell, The Law of the Straits Settlements: A Commentary (Singapore: Kelly & Walsh, 1915), 148–150. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RRARE 348.5957026 BRA). Also see Buckley, An Anecdotal History of Old Times in Singapore, 58. Tanjong Malang is today the end of Shenton Way, near its junction with Prince Edward Road, while what was referred to as Tanjong Katong (or Deep Water Point) would be on the old coast where Still Road meets East Coast Road. ↩

-

This estimate is based on the fact that the 12-pounder smooth-bore British cannons of the early 19th century had a range of about 1.2 km, and Article 1 of the treaty stipulated that the jurisdiction extended “as far as the range of cannon shot, all around the factory”. ↩

-

Buckley, An Anecdotal History of Old Times in Singapore, 39. ↩

-

Buckley, An Anecdotal History of Old Times in Singapore, 39. ↩

-

Buckley, An Anecdotal History of Old Times in Singapore, 39. ↩

-

“Arrangements Made for the Government of Singapore in June 1819”. See Buckley, An Anecdotal History of Old Times in Singapore, 58. ↩

-

Article 1. See Buckley, An Anecdotal History of Old Times in Singapore, 58. ↩

-

Buckley, An Anecdotal History of Old Times in Singapore, 58–59. ↩

-

Raffles Museum and Library, “Farquhar to Raffles, 2 November 1819,” L10: Singapore: Letters to Bencoolen, Straits Settlements Records, 188–190. (From National Archives of Singapore) ↩

-

Raffles Museum and Library, “Raffles to Farquhar, 20 March 1820,” L10: Singapore: Letters to Bencoolen, Straits Settlements Records, 319. (From National Archives of Singapore) ↩

-

Raffles Museum and Library, “Farquhar to Hull, 22 March 1823,” L13: Raffles: Letters from Singapore, Straits Settlements Records, 283–87. (From National Archives of Singapore, microfilm no. NL58) ↩

-

H.F. Pearson, “Singapore from the Sea, June 1823. Notes on a Recently Discovered Sketch Attributed to Lt. Phillip Jackson,” Journal of the Malayan Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society 26, no. 1 (161) (July 1953): 54. (From JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website). This site used to lay a short distance from the seafront as the Padang – then known as The Esplanade – was only half its current width. See Kevin Y.L. Tan, “A History of the Padang,” BiblioAsia 18 no. 1 (April–June 2022). Farquhar’s Residency buildings were eventually abandoned. In 1827, Lieutenant Jackson reported that the old Residency area was “still covered with the decayed attap buildings belonging to Colonel Farquhar”. See Pearson, “Singapore from the Sea, June 1823. Notes on a Recently Discovered Sketch Attributed to Lt. Phillip Jackson,” 55. ↩

-

Chan Gaik Ngoh, “The Kapitan Cina System in the Straits Settlements,” Malaya in History 25 (1982): 74; Wong Choon San, A Gallery of Chinese Kapitans (Singapore: Dewan Bahasa dan Kebudayaan Kebangsaan, 1963). (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSING 325.25109595 WON); Mona Lohanda, The Kapitan China of Batavia, 1837–1942 (PhD diss., School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London, 1994) ↩

-

Raffles Museum and Library, “Farquhar to Raffles, 5 May 1820,” L10: Singapore: Letters to Bencoolen, Straits Settlements Records, 368–73. (From National Archives of Singapore) ↩

-

India Office Factory Records, IOR/G/34/Subseries G/34/153/File 154, “Singapore Diary, 11 May 1827” (p. 65, image 59), TROVE, accessed 3 February 2023, https://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-824111293/view. ↩

-

India Office Library Factory Records: Straits Settlements, IOR/G/34/Subseries G/34/153/File 154, “Singapore Diary, 25 May 1827” (pp. 151–53, images 102–03), TROVE, accessed 3 February 2023, https://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-824120459/view ↩

-

“Extract for a letter from the Honorable the Governor in Council, to the Recorder dated Fort Cornwallis 2d January, 1828” in Minutes and Official Correspondence Between the Government and Sir John Thomas Claridge, Recorder of the Honorable Court of Judicature, Prince of Wales Island, Malacca and Singapore, Commencing in April 1827 and Terminating in September 1829 (Penang: The Government Press, 1830), 13, Google Books, accessed 3 February 2023, https://books.google.com.sg/books?id=2j9pAAAAcAAJ&printsec=frontcover&source=gbs_ge_summary_r&cad=0#v=onepage&q&f=false. ↩

-

India Office Library Factory Records: Straits Settlements, IOR/G/34/Subseries G/34/153/File 156, “Singapore Diary, 7 January 1828” (image 2), TROVE, accessed 3 February 2023, https://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-824199118/view. ↩

-

India Office Library Factory Records: Straits Settlements, IOR/G/34/Subseries G/34/153/File 156, “Singapore Diary, 27 & 28 February 1828” (p. 100, image 126), TROVE, accessed 3 February 2023, https://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-824199118/view. ↩

-

India Office Library Factory Records: Straits Settlements, IOR/G/34/Subseries G/34/153/File 156, “Singapore Diary, 25 February 1828” (p. 98, image 125), TROVE, accessed 3 February 2023, https://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-824198985/view. ↩

-

James William Norton-Kyshe, A Judicial History of the Straits Settlements 1786–1890 (Singapore: Faculty of Law, University of Singapore, 1969), 99. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RCLOS 347.5957 NOR); “Singapore,” Singapore Chronicle and Commercial Register, 5 June 1828, 1. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Notification,” Singapore Chronicle and Commercial Register, 22 May 1828, 1. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Norton-Kyshe, A Judicial History of the Straits Settlements, 99; “Singapore”. ↩

-

Norton-Kyshe, A Judicial History of the Straits Settlements, 99; “Singapore”. ↩

-

“In the Court of Judicature of Prince of Wales Island, Singapore and Malacca,” Singapore Chronicle and Commercial Register, 28 August 1828, 1. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“The Ministry,” Singapore Chronicle and Commercial Register, 20 November 1828, 2. (From NewspaperSG) ↩