Local Music Reaches a Crescendo: The Singapore Record Industry in the 1960s

In this extract from the book From Keroncong to Xinyao, the author looks at why the record industry in Singapore took off in the 1960s.

By Ross Laird!

Despite the significant changes that had taken place in Singapore’s record industry in the 1950s, few could have predicted the even more dramatic transformations to come in the 1960s. At the start of the decade, the record industry in Singapore was still dominated by EMI (which had originally been known as Electric and Musical Industries, hence the initials). The few independent record labels that existed were relatively insignificant in market terms, and no other multinational record company had yet shown an interest in establishing a presence in Singapore.

EMI was famously conservative when it came to signing up local talent in its main Asian markets of Hong Kong and Singapore. The company enjoyed a virtual monopoly in these markets in the early 1960s, and they saw little reason to expand beyond the well-established forms of local popular music.

Most Singapore recordings in the late 1950s and early 1960s were either traditional Chinese opera, or Malay and Chinese film or pop songs of the period sung in Chinese or Malay. There were very few local recordings in English aimed at the emerging youth market, which at the time was almost completely dominated by imported British and American (and some European) records.

"The Recording Industry in Singapore, 1903-1985"

New Competitive Forces Emerge

It was not until 1963 that a new multinational record company would set up operations in Singapore. After a relatively unsuccessful investment in Hong Kong in the 1950s, Philips decided to relocate to Singapore. One of its first decisions in 1963 was to release a record by a Singapore guitar band, a step that would singlehandedly kickstart a process of radical change in the local record industry. This guitar band was The Crescendos, and the rest, as they say, is history.

The Crescendos started out in early 1961 as an all-male three-piece guitar band, and made their first public appearance at the Radio Singapore Talentime Quest in January that year.1 According to press reports,2 John Chee, the leader of The Crescendos, “discovered” 15-year-old Susan Lim just before the start of the 1962 Talentime Quest competition and decided to feature her as the lead vocalist. In reality, Lim had been performing publicly since she was around 12 and was already a seasoned performer by the time she joined the band.3

The Crescendos’ first record, Mr Twister, was announced in February 1963,4 and by October had sold more than 10,000 copies. “Local dealers of Philips records confirmed that since the arrival of The Crescendos’ disc, a similar song by [famous American singer] Connie Francis on another label was ‘dropped’ by buyers who showed a marked preference for The Crescendos.”5

Within 18 months of the success of the first Crescendos release, there was a definite increase in activity within the local record industry. The Singapore branch of Philips began signing local acts quite aggressively and, in the mid-1960s, initiated a series of local records that developed into an exceptionally fine catalogue of Singapore pop releases.6

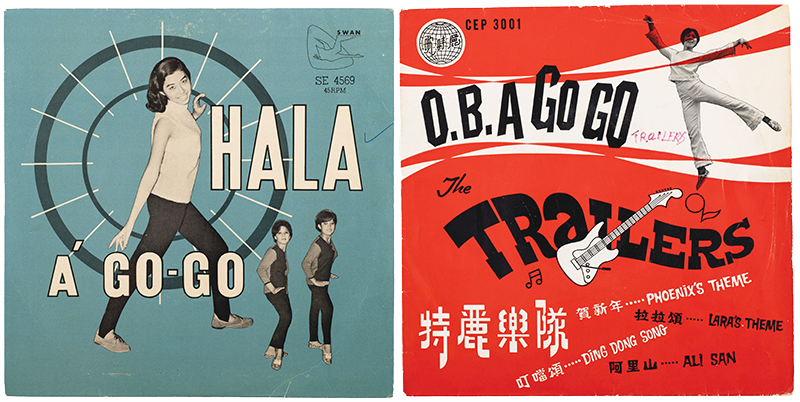

Other labels were quick to follow suit, and new startups such as Cosdel (supported by giant American label RCA that was already active in Japan) and Eagle as well as the long-established EMI began actively recording a wide range of local popular music. In 1966, several new independent Singapore labels entered the market, such as Blue Star, Camel, Olympic, Pigeon, Swan and Roxy (all of which specialised in local artistes). In 1967, the Polar Bear and Squirrel labels were established and in the same year, Decca, another multinational label, also began local recording in Singapore.

From the mid-1960s onwards, the record industry in Singapore developed rapidly, and between 1965 and 1969 alone, over 120 different labels released local recordings.

What is interesting, and has often been overlooked, is that this prolific burst of record industry activity in the 1960s was unique to Singapore. Although Hong Kong was a similar market in many ways, it did not have the same diversity of record labels. Until the late 1960s, no major record labels had recording or pressing facilities in Malaysia, so Singapore also catered to that market. Additionally, there was a big demand for Singapore pressings in Indonesia. Although the latter had a much larger population, no international record companies had set up branches there and only a handful of Indonesian record companies existed.7

Further Developments

By the end of the 1960s, there were hundreds of labels in Singapore catering to every taste, of which about 140 of these labels released local recordings (a majority being independent companies based here).

Apart from supplying the Singapore market, many companies exported a significant percentage of their production, especially to Malaysia and Indonesia. One relatively small producer, Kwan Sia Record Company, which produced the Swan and Star Swan labels, reported that half of its 8,000 copies pressed from a single LP release was exported to Indonesia at a value of about $30,000.8

(Right) O.B. A Go Go, a record released by Cosdel for The Trailers in 1967. This was a local band popular with teenagers in Singapore. Courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

By early 1967, Singapore was producing a total of 2.45 million records annually. According to the Straits Times in May 1967, three record companies – Life Record Industries, EMI Records (Southeast Asia) and Phonographic Industries – were expected to reach a total output of 8.925 million records in five years.9

By 1970, there were at least four record manufacturers in Singapore that pressed records for their own labels as well as for other companies. There were likely other small-scale manufacturers as well, so exact figures are not available, but according to newspaper reports of the time, record production at these four major pressing plants had reached one million discs per month.10

New Markets

The 1960s saw the development of new markets because of economic and social developments as well as an emerging new youth market. While a similar demographic for popular music had existed in Singapore in the 1950s, the youth market then was relatively smaller and almost entirely focused on a diet of imported records by foreign artistes.

In contrast, young people of the 1960s had the funds to purchase records on a larger scale than ever before, and were willing consumers of a local pop culture that was targeted specifically at them. Press coverage and advertisements published on an almost daily basis point to a seemingly endless line-up of concerts, dances, stage shows and live music activities catering to this market.

There was also a rise in the standard of living in 1960s Singapore that led to the creation of a rising middle class who could afford to spend a bigger portion of their income on discretionary items like records and other luxuries. This rising affluence in turn resulted in an unprecedented volume of records of all kinds produced or distributed in Singapore in the 1960s to meet the demands of a growing market.

New Venues

New music and entertainment venues specifically aimed at the youth demographic were added to existing cabarets, nightclubs and dance halls. Some of these older venues also adapted and innovated in order to take advantage of the new group of potential customers. For instance, before the war, on-stage live performances took place before film screenings at the cinemas, but in the 1960s, these performances took the form of pop concerts, especially when they were held in conjunction with films featuring pop stars or had themes relating to pop culture.

Another example was “The Early Bird Show”, which was also held in a cinema, but at an early hour of the morning (hence its name), and not in conjunction with a film screening. “The ‘Early Bird Show’ has played to packed houses at Singapore’s Odeon Cinema. Starting at 8.45 a.m. each week, the show looks like being [sic] with us a long time yet, as it will continue as long as the fans respond,” reported Radio Weekly in July 1967.11

In addition, there were live concerts such as “A Night of Blue Beats”, “Pop Stars on Parade ’66”, “Top Talents ’66”, “What’s Up in Pops” and “Seven Sounds of Soul”. These featured all-star line-ups that differed from conventional concerts usually showcasing a single performer accompanied by one or two supporting artistes.

.png)

Apart from the many one-off concerts held in various halls, there were also regular concert series, including “The Early Bird Show” at the Odeon Cinema (1967–70) and “Musical Express” at the Capitol (1967–68).

Other important platforms for local performers were the regular Talentime competitions and thematic contests such as “Ventures of Singapore Competition”. In some cases, the winning artistes were offered an opportunity to make a record as part of their prize. Talentime and similar competitions had existed since 1949, but during the 1960s they became ever more popular and many winners went on to have significant careers as performers and recording artistes.

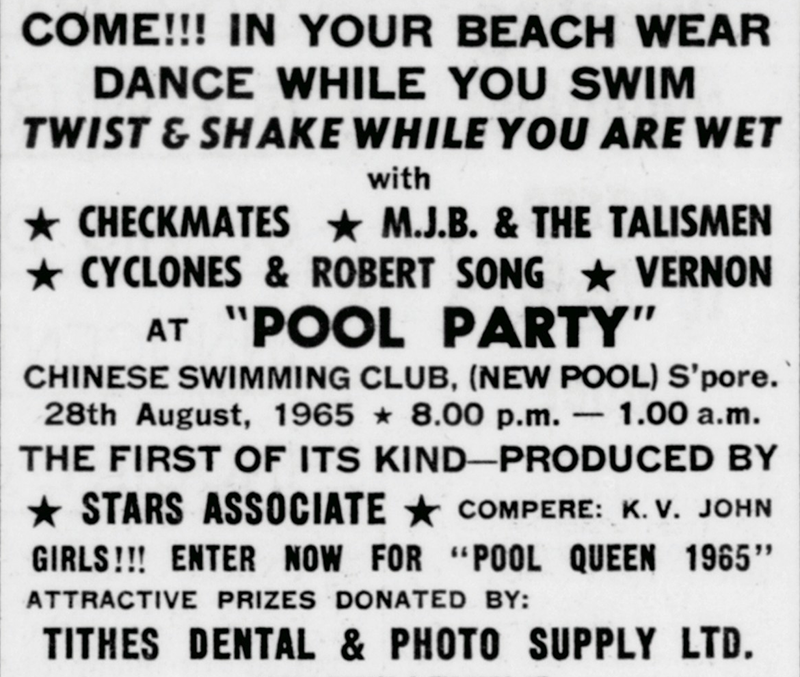

One novel event organised in the 1960s was the series of “Pool Parties” held at the Chinese Swimming Club. Everyone came in their swimsuit and could take a dip in the pool whenever they needed to cool off or in between dancing to the music of live bands.

It is possible to see connections between these modern live music performances and earlier forms of public entertainment such as Chinese street opera (wayang) and Malay opera (bangsawan) performed by travelling opera troupes on open-air stages, and even the relatively more recent getai (literally meaning “song stage”) performances associated with the Chinese Hungry Ghost festival.12

Other outlets for popular music performances in the 1960s were radio and television broadcasts, charity concerts and shows at British military establishments (which despite the more restricted audience reach were important venues for live music). Private parties also provided additional avenues for bands and vocalists to perform on the entertainment circuit.

Taken together, these opportunities to perform publicly encouraged many musically inclined younger Singaporeans to form their own bands or become singers. This, in turn, fuelled the Singapore music scene in the 1960s, as evidenced by the large number and variety of performers who were recorded here.13

New Bands and Genres

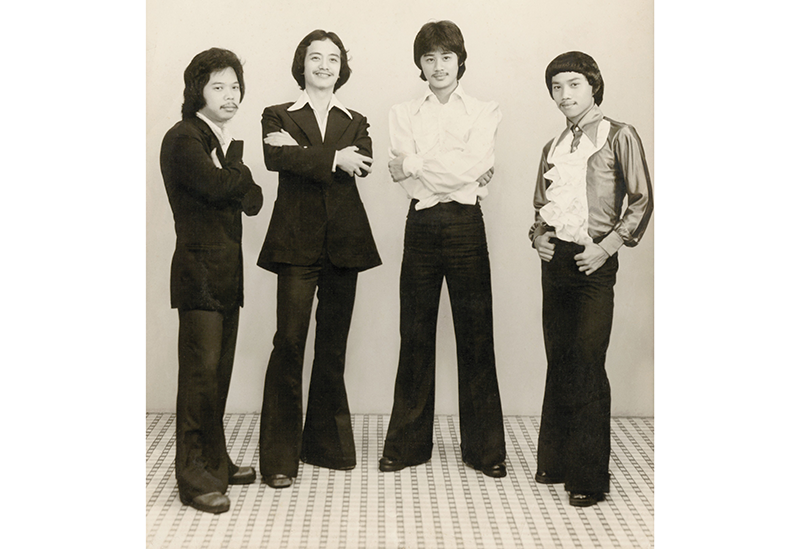

Many new groups formed every year in Singapore in the 1960s. There were over 200 local bands or vocalists who were at a sufficiently professional level to be paid to perform at nightclubs, dance halls, concerts and similar events. Many more were amateur groups or artistes who held full-time jobs and pursued their musical interests after work. While older forms of entertainment such as cabaret-style vocalists were still popular in the 1960s, it was the newer emerging styles such as guitar-driven rhythm-and-blues bands that dominated youth-oriented venues like concerts and tea dances.

A 1967 article in the Sunday Times said:

“Pop music is today a very potent force in Malaysia and Singapore…. The latest beat or sound emanating from Britain and America is heard here within weeks and even days later. Local fans take a remarkably short time to catch on to the latest trends or beat in the pops…. Every new craze is bound to make its way to Singapore and Malaysia where local guitar-twanging groups are ready always to imitate new styles…”14

From the mid-1960s onwards, even the conservative Radio Weekly began devoting several pages in each issue to the latest trends in pop music.

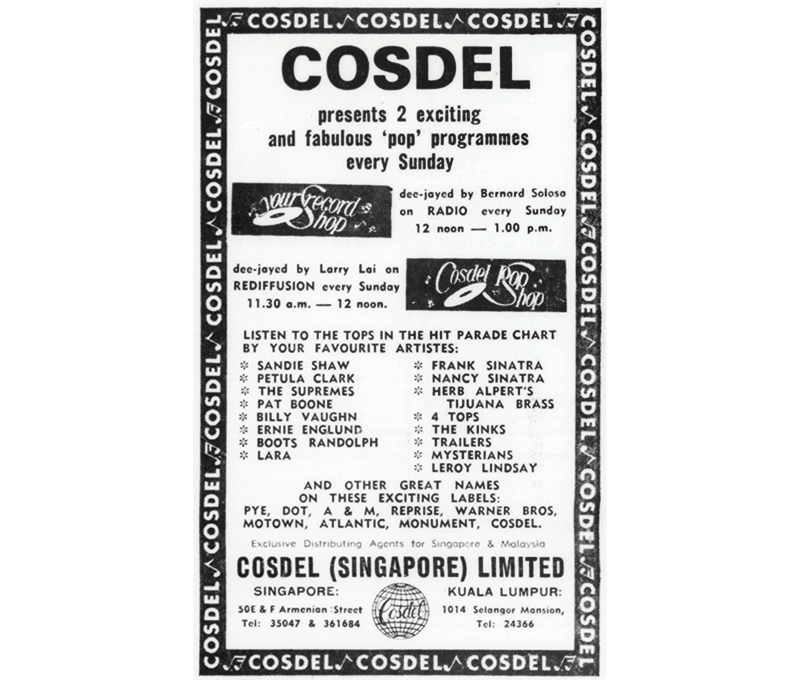

Another new development was sponsored radio programmes devoted to pop music. Cosdel Record Company, for example, promoted two radio shows: “Your Record Shop” on Radio Singapore and “Cosdel Pop Shop” on Rediffusion. These programmes played local records on the Cosdel label as well as imported labels that were distributed by Cosdel.15

By the late 1960s, local popular music was deemed important enough to be treated seriously, with regular columns appearing in daily newspapers and other print media. The lure of a much larger market in Malaysia and Indonesia also gave rise to Malay-language pop music publications that were based in Singapore.16

Many amateur bands and singers were able to develop a following via fan clubs and attracted regular patrons at their performances, even if some of their careers were short-lived. Local record companies were just as eager to tap into these markets as they were in recording the more established performers. Almost every amateur band aspired to record, and although many never did so, there were many more opportunities to cut a record in Singapore during the 1960s than ever before.

Finally, the increasing availability of relatively cheap and reliable air travel within Southeast Asia in the 1960s meant that Singapore bands could frequently tour places like Sarawak, Brunei, Bangkok and Saigon (now Ho Chi Minh City). A few Singapore bands (such as The Quests and The Phantoms) were booked for lengthy appearances in Hong Kong, and even recorded there. On the other hand, bands from Indonesia, Malaysia, Sarawak, Brunei and the Philippines also came to Singapore to perform at hotels and nightclubs or to record in Singapore.17

New Technologies

One reason why multinational companies such as EMI were able to monopolise the record industry in Southeast Asia before the 1960s was due to the large investment required to establish record pressing plants that could manufacture heavy shellac 78-rpm records. At the time, independent record companies could not afford the high cost of setting up their own manufacturing facilities.

In the 1950s, however, record production was revolutionised with the introduction of lightweight vinyl records and, by the 1960s, the cost of equipment needed to produce such records was within the reach of even relatively small record companies. Also, the extensive use of tape recording machines in recording studios by the early 1960s not only reduced the cost of making recordings but simplified the process as well. In addition, record companies in Singapore now had access to privately owned recording studios such as Kinetex and Rediffusion, where they could record material without having to hire EMI’s facilities or set up their own.

All these factors meant that independent record labels were now able to record and produce their own discs at a much lower cost. This alone was a major factor in the surge of record companies in Singapore during the second half of the 1960s.

The Legacy of the 1960s

It is clear that the combination of a number of factors created a unique situation in the 1960s, which saw the Singapore record industry reach unprecedented levels of activity. As many of these factors actually began emerging in the 1950s or earlier, it is essential to view the developments that took place in the 1960s as the outcome of several different processes that fortuitously came together during this decade.

Like almost everywhere else in the world, Singapore was influenced by 1960s pop culture and garage bands (instrumental groups formed by teenagers who played more for fun than anything else) that became part of the local scene. In the 1960s, it was still possible to achieve a level of success and even make records without turning professional. This was why many recording artistes chose not to make music their full-time occupations. For instance, the Singapore all-girl band The Vampires started in 1965 when all its members were still in school.

Despite the many new developments in the entertainment scene and the dramatic spike in record industry activity, other aspects of the Singapore music scene were not that much different from what they had been in the 1950s. While there was still a limited number of professional bands and singers, there was a large pool of undiscovered amateur talent who appeared in Talentime quests and other similar events, charity concerts, parties, and occasionally professional concerts or dances.

As the local press devoted more space to its coverage of popular music, we have a more accurate picture of 1960s popular culture in Singapore compared to previous decades. Clearly, the youth culture and the dynamism of the 1960s made this period an especially fascinating one in the development of Singapore’s musical culture.

This is an edited chapter from the book, From Keroncong to Xinyao: The Record Industry in Singapore, 1903–1985, by Ross Laird and published by the National Archives of Singapore (2023). The publication is available for reference at the Lee Kong Chian Reference Library and for loan at selected public libraries (call nos. RSING 338.4778149095957 LAI and SING 338.4778149095957 LAI). It also retails at major bookstores as well as online.

Ross Laird is the author of From Keroncong to Xinyao: The Record Industry in Singapore, 1903–1985. He was formerly with the Australian National Film and Sound Archive in Canberra. In 2010, he was a Lee Kong Chian Research Fellow at the National Library, Singapore. He currently resides in Brisbane, Australia, with his wife Dao and cat Mimi.

Ross Laird is the author of From Keroncong to Xinyao: The Record Industry in Singapore, 1903–1985. He was formerly with the Australian National Film and Sound Archive in Canberra. In 2010, he was a Lee Kong Chian Research Fellow at the National Library, Singapore. He currently resides in Brisbane, Australia, with his wife Dao and cat Mimi.NOTES

-

These events, and the growing popularity of The Crescendos, took place well before British group The Shadows performed in Singapore in November 1961. Writer Joseph C. Pereira states that the rise of Singaporean guitar bands was sparked by The Shadows’ 1961 performances in Singapore. See Joseph C. Pereira, Apache Over Singapore: The Story of Singapore Sixties Music, Volume One (Singapore: Select Publishing, 2011), 1. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSING 781.64095957 PER) ↩

-

For example, see Ken Hammonds, “Spinning With Cutie Susan,” Straits Times, 3 March 1963, 9. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“The Three ‘Jay Walkers’ of Katong Convent,” Singapore Free Press, 17 May 1960, 5; “Popular Young Trio Had Audience Cheering at a Christmas Concert,” Singapore Free Press, 7 January 1961, 8. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Crescendos Make First Record,” Radio Weekly, 18 February 1963, 1. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RCLOS 791.44095957 RW) ↩

-

“Crescendos’ Disc Sales Top the 10,000 Mark,” Radio Weekly, 7 October 1963, 1. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RCLOS 791.44095957 RW) ↩

-

Philips was the first multinational record company to establish a record pressing plant in Singapore. It officially opened on 24 November 1967. ↩

-

One cannot directly compare Singapore’s record industry with that of Indonesia’s as there are several important differences between the two countries (Indonesia, for instance, had a relatively small middle class at the time despite its much larger population). During the 1960s, most record labels in Indonesia were produced by a few large corporate entities. There was a government-owned record label called Lokananta, which had a few subsidiaries, and almost all the other labels were owned by Indonesian Music Co. Irama Ltd. (Irama), Republic Manufacturing Co. Ltd. (Remaco, Bali, Diamond, Mutiara, etc.), Dimita Moulding Industries Ltd. (Mesra) and El Shinta Broadcasting System (El Shinta, Jasmine). EMI had no direct presence in Indonesia (except through imports) and Philips also had limited access to that market except under licence or later (from 1968) through imports from Singapore. ↩

-

“Local Made ‘Pop’ Records Go to Indonesia,” Straits Times, 24 May 1968, 14. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Chan Bong Soo, “Gramophone Record Industry in S’pore Big Business,” Straits Times, 19 May 1967, 12. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Lawrence Wee, “Singapore’s Recording Firms Hit Happy Note,” Straits Times, 11 May 1970, 10. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“The Early Bird Show,” Radio Weekly, 24 July 1967, 3. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RCLOS 791.44095957 RW) ↩

-

Getai are performances of songs staged during the seventh month of the lunar calendar. See Jamie Koh and Stephanie Ho, “Getai,” in Singapore Infopedia. National Library Board Singapore. Article published 25 February 2015. ↩

-

The author estimates that there were over 1,500 singers or bands who recorded in Singapore during the 1960s. Some of these were artistes from Malaysia and Indonesia who came here to record and were not residents (although many took the opportunity to perform publicly while they were here). ↩

-

Yeo Toon Joo, “Fanomania,” Straits Times, 21 May 1967, 10. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Page 12 Advertisements Column 2,” Straits Times, 21 May 1967, 12. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

In 1969, Radio Weekly was discontinued and replaced by a new entertainment magazine called Fanfare, which featured regular articles on new groups and trends in popular music. There was also a Malay-language magazine titled Bintang dan Lagu, which began publication in 1966 and ran until at least 1967, with well-illustrated articles on current groups and listings of new record releases. By 1967, even Malay film magazines such as Purnama Filem were featuring articles on the latest pop bands. ↩

-

For example, it was reported in 1969 that a group of 30 Indonesian singers had come to Singapore to record at Kinetex Studios. The newspaper article does not indicate the organiser of this event but states that the artistes included Vivi Sumanti, Bing Slamet and Tanti Josepha, and that they intended to record “250 songs in Malay, Indonesian, Chinese, English and several European languages”. The unnamed organiser was in fact Philips record company, and the recordings appeared on their PopSound label for sale in Indonesia (although the label was also distributed in Singapore, Malaysia and probably elsewhere). The article also states that the artistes would stay in Singapore for three months, recording almost every day and “cutting over 70 EPs and 25 LPs”. See Maureen Peters, “S’pore May Soon Become the Recording Centre for all South-east Asia,” Straits Times, 25 October 1969, 8. (From NewspaperSG) ↩