The Process of Restoring the Chappell Concert Grand

Repairing the National Library’s Chappell concert grand was no easy task. Zhivko Girginov describes the challenges he faced.

It took me three months to restore the National Library’s Chappell concert grand and I spent close to 400 hours altogether. During this process, I made some intriguing discoveries that I had not seen before in other historic pianos.

The British manufacturer Chappell had used a plastic material called Ivoette (one of the earliest acrylic applications used in the manufacture of pianos) over the white keys. Although I have spent many years restoring old pianos, this is actually the first time I’ve seen Ivoette. Ivoette is meant to resemble ivory and it explains why the keys of the Chappell appear slightly yellowish rather than completely white. The plastic covering was not only glued to the wooden keys but also reinforced with four copper pins per key. This ensured that the Ivoette would not detach due to the tropical conditions in Singapore.

I first used a sanding machine to strip off around 0.1 mm of the Ivoette to remove the uneven shades of yellow on the white keys. After polishing, the surface now appears brighter and even, while scratches have also been removed. I also painted the wooden sides of the keys in gold to match the interior cast iron plate of the piano.

To mask the deep scratches on the black keys, I covered them with floral “baroque” design strips followed by two coats of polyurethane to achieve a hard and glossy surface. I applied the same floral design feature to other parts of the piano to create some visual accents, which breaks the monotony of the even black surfaces.

Those were relatively easy to fix. What was a bigger challenge was repairing the piano’s action. The action is the mechanism that causes the hammers to strike the strings when a key is pressed. In the Chappell, it had deteriorated to the point that the keys were barely functioning.

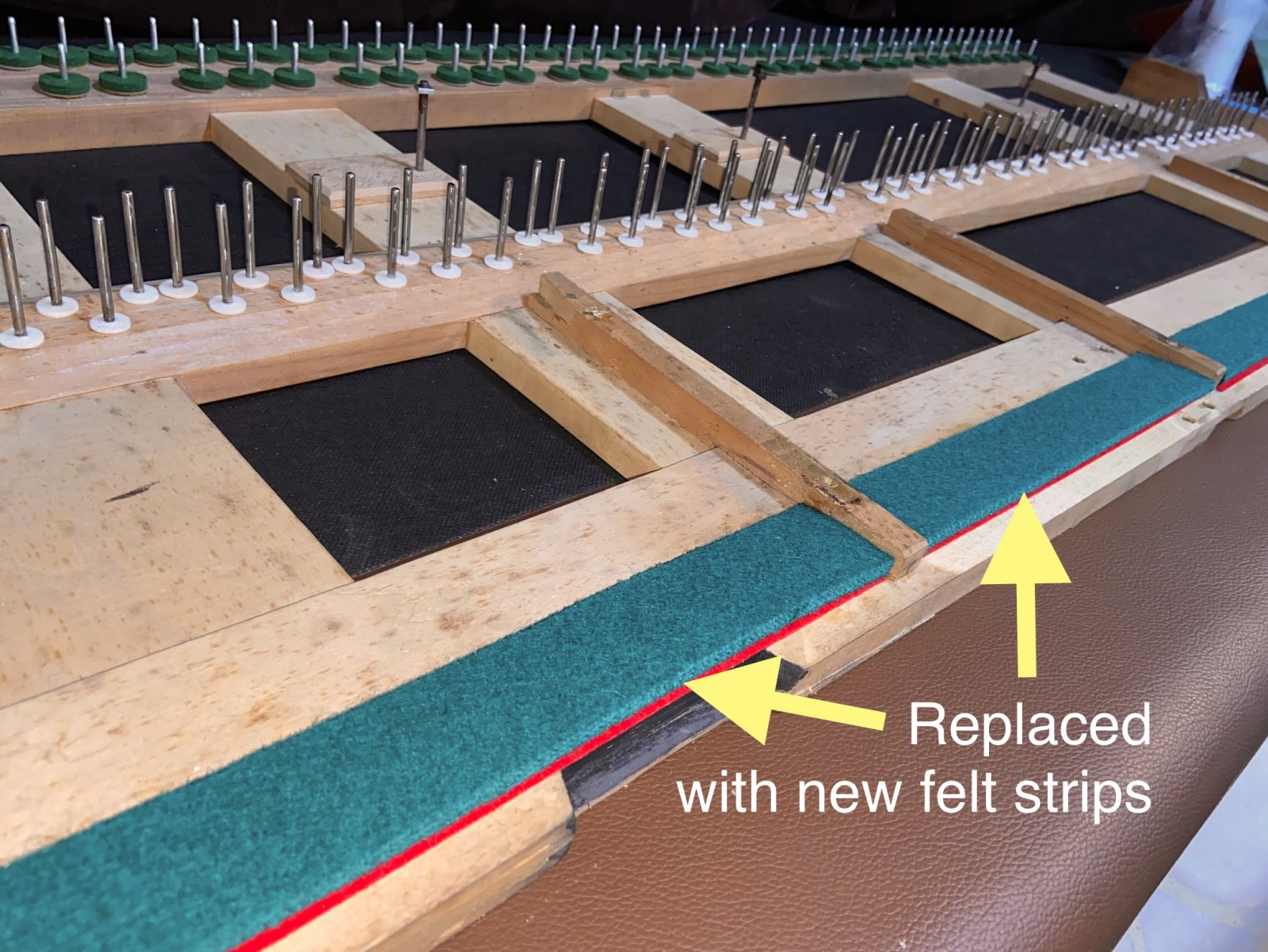

To restore the keys, I dismantled the entire action so that I could reach the parts inside to repair and lubricate. Once it was dismantled, I replaced all the felt strips and other felt parts inside the action. I also had to bring the friction levels of all the centre pins to about 4 gr. The centre pin forms the metal axis core of the wooden flange, which is the hinge of the hammer. If the friction is too great, the flange will not work and pressing the piano key will not result in any sound at all, or it will cause the key to remain depressed. I found that in some of the centre pins, the friction level was over 40 gr, which explains why some of the keys were not working initially.

During the restoration, I also noticed that the felt covering the heads of the hammers was extremely hard. After reading the BiblioAsia article “A Grand Piano’s Chequered History” about the unfortunate fate of this instrument and the criticisms surrounding it, I realised that the major mistake the piano manufacturer made in 1952 was that they applied too much lacquer onto the sides of the hammer heads.

Lacquer is commonly used to bring out a brighter and “shiny” sound during the piano voicing process (adjusting the density of the felts covering the hammers to improve tone quality). However, applying too much lacquer to the felt causes the lacquer to soak deep into the hammer heads. This is irreversible.

Today, we have special pliers with attached needles to prick the felt, which helps. Besides pricking the felt, I also applied a special chemical softener liquid that penetrated and relaxed the wool fibres of the felt. This reduced the harshness of the sound somewhat.

The main thing that particularly surprised me was to find that the piano’s manufacturer had mostly used trichords (three thin strings per key) in the lower bass register (notes below the Middle C) instead of a single thick string per key (monochords). Only the eight leftmost bass keys were monochords. Keys with three strings each will never produce a dense, long lasting and rich bass sound, compared to keys with a single string each, which are heavier and would vibrate much longer.

Furthermore, bass keys with trichords tend to get out of tune more easily than keys with monochords. This helps to explain why the top master pianists at the time had so many complaints about the sound of the Chappell. The construction of the piano was inherently wrong from the start and cannot be reversed, unless all the trichords are replaced with monochords. If only I could travel back in the time to inform the manufacturer to use monochords for the bass notes, the fate of this glorious grand piano would probably have been very different.

I am happy to be given the opportunity to restore this unique instrument and give it a new lease of life. It is a precious piece of Singapore history and ought to be preserved in a playable condition so that it can continue to bring joy and pleasure to Singaporeans in the years ahead.

All photos courtesy of Zhivko Girginov.