A Well-Choreographed Move: From Singapore Dance Theatre to Singapore Ballet

As the history of the company shows, its new name is less about breaking away from the past as it is about leaping confidently into the future.

By Thammika Songkaeo

One of Singapore’s oldest professional dance companies has become one of its newest. On 10 December 2021, Singapore Dance Theatre (SDT) announced that a little over 30 years after it was first unveiled to the public, it was jettisoning its old name and embracing a new one – Singapore Ballet.

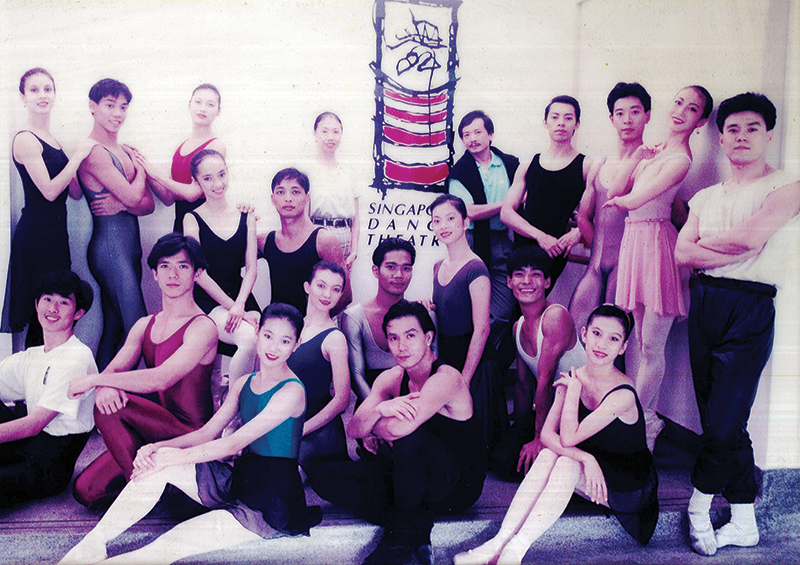

The new name is perhaps the most potent symbol of how much the company has changed and grown since its public debut at the Singapore Festival of the Arts in 1988. At the time, the company was unknown; it had just seven dancers and its future looked uncertain. Today, the company has grown to 35 dancers and apprentices of various nationalities, with a loyal following locally and an international profile as well. Janek Schergen, its artistic director, receives applications from aspiring dancers daily.1

The company has made a name for itself in numerous festivals and events such as Le Temps d’Aimer la Danse in Biarritz, France; Mexico’s Festival Internacional Cervantino; Chang Mu Arts Festival in Korea; and the Philippines Festival of Dance.

From the Get-Goh

While many individuals have played an important role in the company’s journey, no retelling of its history would be complete without considering the contributions of the Goh siblings – Goh Soo Nee (who also went by Goh Soonee and Soonee Goh), Goh Soo Khim and Goh Choo San. The three siblings played vital roles, though in very different ways: Soo Nee prepared the ground by starting an important predecessor institution to SDT; Soo Khim, on the other hand, led the company during its fledgling years; and although Choo San died prematurely, he was, and continues to be, spiritually influential, as can be seen by the fact that the company continues to restage his ballets, even till today.

Although the company was founded in the late 1980s, the seeds of the company were planted four decades earlier when Soo Nee followed her ballet teacher to Australia to train at the Francis Scully Ballet School, before moving to London where she auditioned for the highly competitive Royal Ballet School. In her oral history interview with the Oral History Centre, she recalled strongly the exhilaration then. “It was very exciting for me because the training is very intensive,” she said, “and I like[d] it very much.”2

After Soo Nee returned to Singapore in 1955, she co-founded the Malaya School of Ballet in 1956. In 1958 the school merged with the Frances School of Dancing – that was led by two well-known dancers then, Vernon Martinus and Frances Poh – to become the Singapore Ballet Academy (SBA). It soon became the home for Singapore’s aspiring dancers, including Soo Nee’s younger siblings.3

The SBA soon gained a reputation as an excellent dance school, but its dancers faced a dilemma: as Singapore did not have a local professional dance company, any student who developed a deeper interest in dance had to go abroad for further studies or to pursue a career in dance, as Soo Nee herself had done.

That was also what her younger sister Soo Khim did, or at least tried to do. Soo Khim trained at the SBA from 1958 and then at the Australian Ballet School in Melbourne from 1964.4 Like Soo Nee at the Francis Scully Ballet School, Soo Khim was the only Asian student at the all-white Australian Ballet School.5 She had dreamt of a professional dance career in Australia, but faced discrimination there due to her ethnicity.6 Ballet, as a professional industry, had always favoured homogeneity, with a penchant for Caucasian dancers.7

After graduating in 1966, Soo Khim returned to Singapore and joined her sister Soo Nee as a principal trainer at the SBA. When Soo Nee emigrated to Canada, Soo Khim took over the reins as director and principal in 1971.8

At one point, the third Goh sibling, Choo San, had been hailed by the New York Times as “the most sought after choreographer in America”. Beyond being a successful dancer himself, he was also a renowned choreographer to the point that Mikhail Baryshnikov, one of the leading male dancers in the United States and a noted dance director, commissioned Choo San to create a work for him, which premiered in 1981.9 “From my point of view, he’s one of the few young choreographers who has musical instinct,” recalled Baryshnikov. “He works… with such happiness. He never suffers. He’s very sure.”10

Choo San went on to create works for Joffrey Ballet, Houston Ballet, Pennsylvania Ballet, Boston Ballet and Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater,11 before eventually becoming the associate artistic director of the Washington Ballet in 1984.12

That same year, Francis Yeoh, founding artistic director of the Singapore National Dance Company, approached Soo Khim and Anthony Then, a dancer and choreographer, to helm the ballet section of the National Dance Company.13 Inspired by the Washington Ballet – which had performed Choo San’s In the Glow of the Night and the internationally acclaimed14 Fives at the 1982 Singapore Festival of Arts – Soo Khim and Then decided to form a company of approximately the same size and artistic vision.15

Originally, the plan was that Choo San’s works would provide the foundation of this new company’s repertoire. Fate, however, intervened. On 28 November 1987, Choo San died from an illness. He was only 39.16

Pas De Deux: It Takes Two

In 1987, Soo Khim and Then registered the new company as Singapore Dance Theatre, a name they chose to reflect a wider repertoire for the company, which would range from modern works to classical ballets, and which would include an Asian sensibility. (Soo Khim continued in her role as director of SBA even after the dance company was set up.) They wanted to develop Singaporean dancers and interest audiences in works with an Asian influence. Goh also felt that the label of “Dance Theatre” provided the freedom to explore and experiment with more diverse works.17 Choo San’s death had been a severe blow, but the founders decided to go ahead.

Speaking at the official launch of SDT in 1988, Second Deputy Prime Minister Ong Teng Cheong described the founding of the company as “timely” and said that it was “in line with the Government’s vision to transform Singapore into a cultured society by 1999, and in promoting excellence in the arts. It therefore deserves the support of every citizen”.18

Warming Up to Challenges

The fledgling SDT struggled financially in its initial years. Fortunately, Then and Soo Khim had friends who would help form SDT’s board (though none were particularly familiar with the professional world of dance), and together they were able to secure financial support from fundraisers and government bodies, such as the Ministry of Culture, which disbursed $70,000.19

This amount, however, was not sufficient to secure all their needs, a primary one being a suitable rehearsal space. In the beginning, SDT had to share space with the SBA and schedule its rehearsals only when SBA classes were not in session. The SBA studio was also not properly equipped for rehearsals. Business Times journalist Lisa Lee described the scene she had witnessed there in 1988:

“Hey your foot almost hit my face,” says one dancer.

“I’m sorry,” croons her male neighbour in a distinct Filipino accent.

“Well, you can kick him back when we turn around to the other side,” quips another. They laugh.20

SDT needed a place of its own – and fast. To work, the studio had to be column-free with changing and bathroom facilities. But finding a suitable space was not easy, especially as limited budgets “produced some duds like an old disused warehouse” with columns.21

Refurbished barracks at Fort Canning were finally chosen in 1990, although Schergen recalls that the premises were “a bit shabby”.22 The facilities included three dance studios, a props store and workshop, a wardrobe room and a cafeteria. While the Public Works Department spent $4.62 million on renovations, SDT paid for the “fitting out of the interior of its part of the building’’, which was estimated at $500,000.23

SDT’s new premises paved the way for “Ballet Under the Stars”, first staged at Fort Canning Green in April 1995. Immediately, the inaugural event helped the company reach out to people who had never attended ballet performances and who might have been intimidated by formal theatre settings. Ticket holders were encouraged to bring picnic baskets and mats, and enjoy the ice-cream and popcorn sold at the venue. “Ballet Under the Stars” has been held almost every year since 1995, and is today a well-loved and iconic outdoor dance event enjoyed by all.

Unfortunately, in December that year, the company suffered another major blow when co-founder Then died following an illness. His death, at 51, created another void, which Soo Khim felt profoundly. “I have not only lost a great friend but also a confidant,” she said.24 With only Soo Khim left at the helm, the company needed assistance.

For help, the company looked abroad, and a number of renowned dancers, teachers and choreographers such as Timothy Gordon, David Peden, Andrea Pell, Maiqui Manosa, Paul de Masson and Edmund Stripe stepped in. They taught the company’s daily classes, ran rehearsals and took the repertoire onto the stage.

Although Then and Soo Khim had been able to contribute their own original works – such as Concerto for VII (Then), Schumann Impressions (Then), Brahm’s Sentiments (Soo Khim) and Environmental Phrases (Soo Khim) – shaping the SDT to be an internationally recognised name required more, not only in terms of the number of dancers and works performed, but also in how the works would shape and create an identity for the company.

In the beginning, SDT did not focus on works that would help define its identity, according to Schergen. Instead, engaging choreographers was more a matter of convenience and availability. At the time, the pertinent questions asked when appointing a choreographer were “Who was available? Who could they get who was not busy”, rather than “Who could really develop the company?” said Schergen. “The identity of the company is so valuable and so important that you have to know who you are first and then plan to be that,” he said. “The problem with SDT in its early years was that there wasn’t a clear idea of where the company was heading.”25

It was only after seeing the positive response to a staging of its first full-length classical ballet, The Nutcracker, in 1992 and “Ballet Under the Stars” in 1995 that the SDT decided to do more full-length ballets while keeping to an eclectic repertoire. However, this was easier said than done. “None of those things sit comfortably together,” Schergen said. “Are we a classical ballet company that does contemporary work, or are we a contemporary company that does classical work badly? What are we? And we’re called Singapore Dance Theatre, which isn’t a ballet company.”26

Growing by Leaps and Bounds

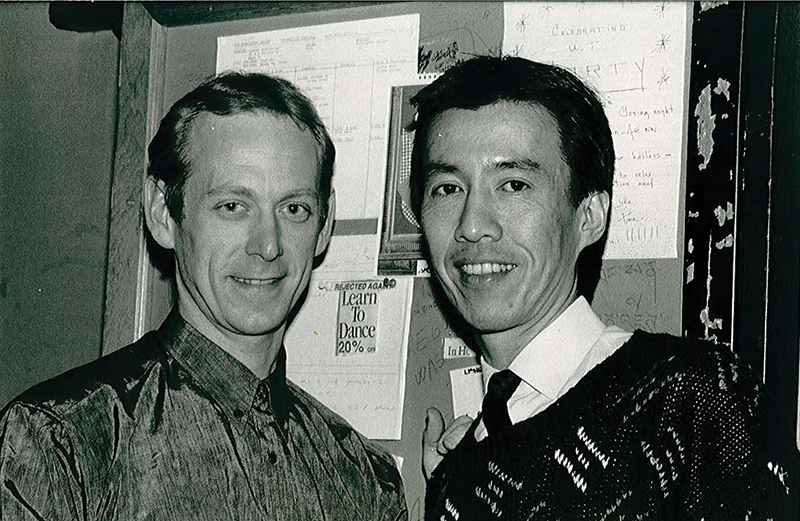

Although Schergen only officially joined SDT as its assistant artistic director in 2007 (and assumed the role of artistic director one year later), his influence dates to the very founding of the company itself.

Schergen had been involved with the company as a consultant at its inception, training its dancers for their debut performances in 1988. This involvement came as a result of a personal connection; Schergen, a Swedish American, had been a close friend and collaborator of Choo San. “What he said to me…,” Schergen recalled “was ‘Help [Soo Khim] get it started’ so that was my directive.”27

Schergen had more than the necessary qualifications: he had been the ballet master for companies such as the Washington Ballet, Royal Swedish Ballet, Pittsburgh Ballet Theatre and Norwegian National Ballet. Schergen had also staged Choo San’s works for the SDT between 1988 and 2005, flying in while being based abroad. (Schergen is also the artistic director of the Choo-San Goh & H. Robert Magee Foundation, which oversees the licensing and production of Choo San’s ballets.)

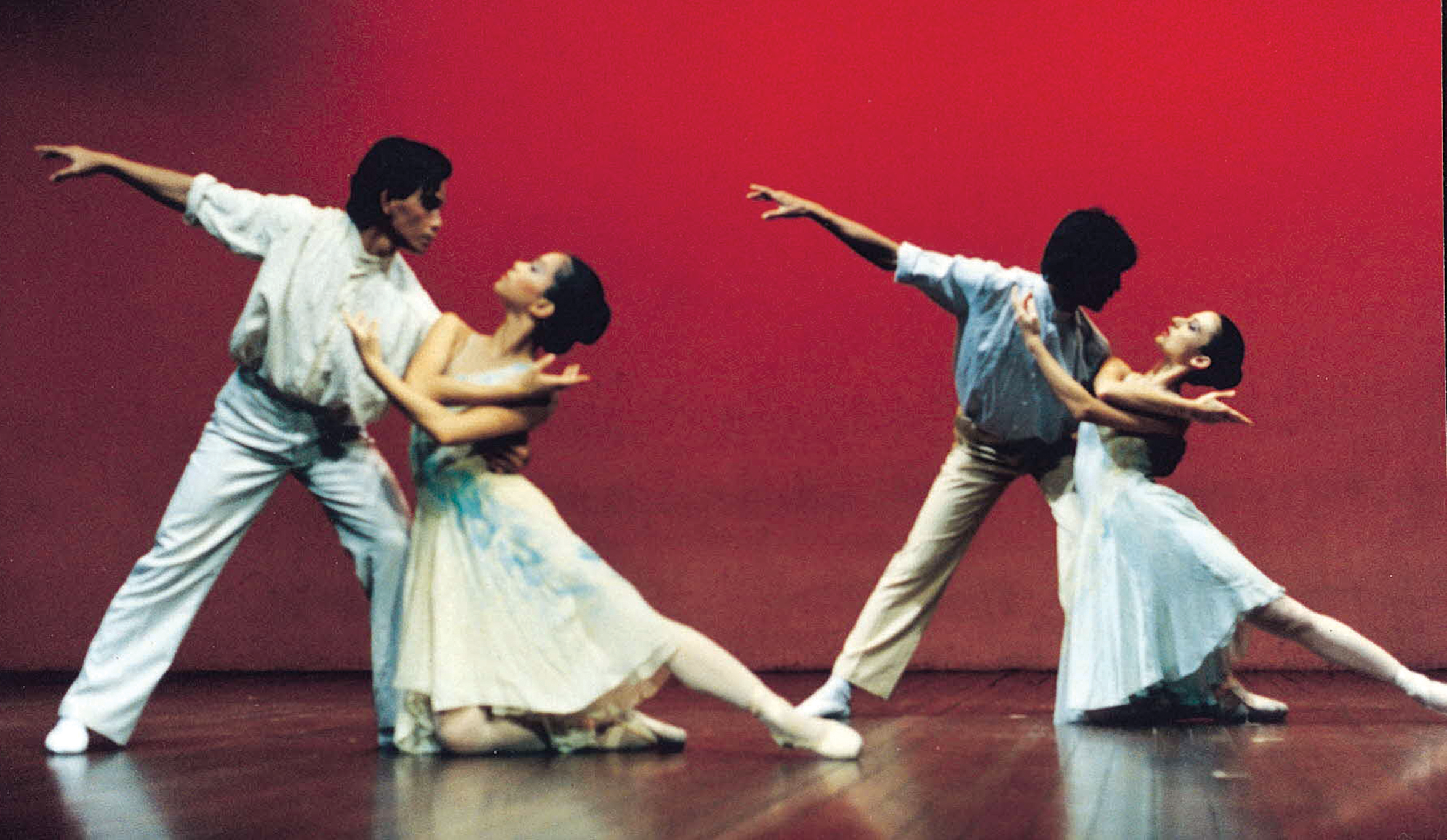

One of Schergen’s initial tasks as a consultant was to help the dancers learn Choo San’s ballets, including Beginnings, Momentum and Birds of Paradise. This was no easy task as his ballets are “marked by a first-rate command of structure and fluency”, as Choo San’s obituary in the New York Times noted.28

To push the dancers, Schergen gave them marginally difficult challenges each time. “[It] was a little bit like you [push] them a little bit harder, they’d meet that, a little bit harder, they’d meet that,” he explained.29

It was particularly challenging as some of the dancers in the company in the early years did not have the requisite training. Founding dancer Jamaludin Jalil, for instance, had taken up dance as a hobby; he was actually trained as a lawyer. Speaking to the Straits Times in 1988, he said: “Before we embarked on this, most of us danced about 12 hours a week. Now we’re doing 12 hours in two days.”30

Flying in regularly as a consultant and guest choreographer allowed Schergen to become familiar with the company and the dancers as he helped them prepare for their performances. But there is only so much that one person can do for a dance company on a part-time basis. Although Choo San had hoped for Schergen to be more involved with the company right from the beginning, enticing Schergen to move to Singapore was a challenge.31 Schergen’s career was soaring abroad, and just before he became the SDT’s assistant artistic director in 2007, he had been the ballet master of the Norwegian National Ballet.32 But when Schergen finally agreed to relocate to Singapore to take up the mantle at SDT, he made sure to run the company right.

Schergen brought with him a wealth of experience in running a ballet company sustainably, from hiring choreographers to fundraising and staging performances. As artistic director, Schergen was (and still is) responsible for daily classes at the company, teaching and rehearsing the company’s repertoire. By end 2020, he had commissioned 31 world premieres and launched 19 company premieres. He also developed a suite of outreach and capacity development programmes, including the Ballet Associates Course, The Ambassadors Circle, Scholars Programme, One @ the Ballet, Celebration in Dance, The SDT Choreographic Workshop and The Intensive Ballet Programme.33

In 2013, Schergen oversaw SDT’s move into spanking new premises at the Bugis+ mall on Victoria Street. Its location within the Bugis arts and cultural district allows the company to further engage the public through its education and outreach programmes.34

Most importantly, under Schergen, the company began to address the critical question of whether it is a classical ballet company that does contemporary works, or a contemporary company that does classical works. Over time, the company began adding more and more full-length classical ballets such as Giselle and Coppélia to its repertoire. While these were well received by audiences, Schergen knew that the burgeoning emphasis on classical ballet meant that the company’s name – Singapore Dance Theatre – was looking increasingly ill-fitting.

The name change in December 2021 was thus long overdue, according to Schergen. “By the time three decades had passed, a confident maturity to SDT was now in place and the company had its own unique identity,” he said. “To reflect this and show this confident maturity of the nature of our organisation, a decision has been made to rename ourselves as Singapore Ballet.”35

Always En Pointe

In 2023, Singapore Ballet celebrates its 35th anniversary. Among the highlights of its season for the year are “Masterpiece in Motion” in July, which includes Goh Choo San’s Configurations originally created for Baryshnikov that premiered in 1981, “Ballet Under the Stars” in September and the world premiere of Schergen’s Cinderella in December.36 Back in May, the company performed at Our Tampines Hub’s Festive Arts Theatre for the first time, stepping not only into the hearts of Singaporeans, but also into the heartlands.

After three and a half decades, Singapore Ballet has become a part of the nation’s artistic and cultural spirit. Today, as the company continues to carve out a path for itself, it can look towards to its future with hope. Armed with a new-found confidence in its identity, Singapore Ballet is poised to soar to greater heights.

Thammika Songkaeo is a resident of Singapore and the creative producer of Changing Room (www.twoglasses.org), a dance film and interactive screening experience. A student of ballet, Latin and street styles, she holds a Master of Fine Arts degree in creative writing from the Vermont College of Fine Arts. She is also an alumna of Williams College in Massachusetts and the University of Pennsylvania.

Thammika Songkaeo is a resident of Singapore and the creative producer of Changing Room (www.twoglasses.org), a dance film and interactive screening experience. A student of ballet, Latin and street styles, she holds a Master of Fine Arts degree in creative writing from the Vermont College of Fine Arts. She is also an alumna of Williams College in Massachusetts and the University of Pennsylvania.NOTES

-

Janek Schergen, interview, 21 December 2022. ↩

-

Goh-Lee Soonee, oral history interview by Mark Wong, 24 July 2012, MP3 audio, Reel/Disc 2 of 4, National Archives of Singapore (accession no. 003755) ↩

-

“Two Gohs With Twinkle Toes Are Returning,”Straits Times, 9 March 1955, 5; “Malaya to Have Ballet Company,” Singapore Free Press, 14 January 1956, 7; Anthony Oei, “Two Ballet Schools Merge to Form an Academy,” Straits Times, 27 April 1958, 11. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Her World Woman of the Year 2008: Goh Soo Khim,” Her World, 17 August 2008, https://www.herworld.com/gallery/woman-of-the-year/goh-soo-khim-woman-of-the-year-2008/. ↩

-

Goh-Lee Soonee, oral history interview, Reel/Disc 2 of 4. ↩

-

Janek Schergen, interview, 21 December 2022. ↩

-

Rohina Katoch Sehra, “How Ballerinas of Colour are Changing the Palette of Dance,” HuffPost, 10 February 2020, https://www.huffpost.com/entry/ballet-dancers-of-color_l_5e14b343c5b66361cb5b6b5f. ↩

-

“The Co-Founder – Ms Goh Soo Khim (1944),” Singapore Ballet, last accessed 7 April 2023, https://singaporeballet.org/interview-goh-soo-khim/. ↩

-

“The Ascent of Goh Choo San,” Singapore Monitor, 5 June 1984, 18. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“The Dancer and the Dance (1982) (Mikhail Baryshnikov Documentary - Full HQ),” Youtube, 9 September 2022, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9piDxc-CWiE. ↩

-

Janek Schergen and Goh Soo Khim, Goh Choo San: Master Craftsman in Dance (Singapore: Singapore Dance Theatre, 1997). (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 792.82 SCH) ↩

-

Sharon Teng, “Goh Choo San,” in Singapore Infopedia. National Library Board Singapore. Article published 2016. ↩

-

Francis Kim Leng Yeoh, “The Singapore National Dance Company: Reminiscences of an Artistic Director,” SPAFA Journal 3 (19 September 2019), https://www.spafajournal.org/index.php/spafajournal/article/view/610. ↩

-

“Goh Choo San,” Off Stage, 12 October 2016, https://www.esplanade.com/offstage/arts/goh-choo-san. ↩

-

Janek Schergen, interview, 21 December 2022. ↩

-

Janek Schergen, interview, 21 December 2022; “Goh Choo San Dies,” Business Times, 1 December 1987, 20. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Janek Schergen, interview, 21 December 2022; Singapore Dance Theatre, Touches: 10 Years of the Singapore Dance Theatre (Singapore: Singapore Dance Theatre, 1988), 13. (From National Library, call no. RSING 792.8095957 TOU) ↩

-

Ong Teng Cheong, “Official Launch of the Singapore Dance Theatre,” speech, Royal Pavilion Ballroom, Inter-Continental Singapore, 4 March 1988, transcript, National Archives of Singapore (document no. otc19880304s). ↩

-

Germaine Cheng, Momentum: 25 Years of Singapore Dance Theatre (Singapore: Singapore Dance Theatre, 2015), 1. (From PublicationSG) ↩

-

Lisa Lee, “All for the Love of Dance,” Business Times, 21 March 1988, 11. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Lee, “All for the Love of Dance.” ↩

-

Ong Soh Chin, “Singapore Dance Theatre to Move into Fort Canning Home,” Straits Times, 30 March 1990, 31. (From NewspaperSG); Cheng, Momentum: 25 Years of Singapore Dance Theatre, 1. ↩

-

Ong, “Singapore Dance Theatre to Move into Fort Canning Home.” ↩

-

“Singapore Dance Theatre Co-founder Anthony Then Dies,” Straits Times, 19 December 1995, 24. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Janek Schergen, interview, 21 December 2022. ↩

-

Janek Schergen, interview, 21 December 2022. ↩

-

Janek Schergen, interview, 21 December 2022. ↩

-

Jennifer Dunning, “Choo San Goh, a Choreographer Hailed for Inventive Dance Forms,” New York Times, 30 November 1987, https://www.nytimes.com/1987/11/30/obituaries/choo-san-goh-a-choreographer-hailed-for-inventive-dance-forms.html. ↩

-

Janek Schergen, interview, 21 December 2022. ↩

-

Jennifer Koh, “And Now, a Professional Dance Group,” Straits Times, 5 March 1988, 13. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Janek Schergen, interview, 21 December 2022. ↩

-

“Janek Schergen,” Singapore Ballet, last accessed 5 May 2023, https://singaporeballet.org/artistic-team/janek-schergen/. ↩

-

Michelle Sciarrotta, “Janek Schergen: Interview with Singapore Dance Theatre’s AD,” TheatreArtLife, 25 December 2020, https://www.theatreartlife.com/dance/janek-schergen-interview-with-singapore-dance-theatres-ad/. ↩

-

Huang Lijie, “New Home for Singapore Dance Theatre,” Straits Times, 31 December 2012, 6. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Dewi Nurjuwita, “Singapore Dance Theatre Unveils Its New Name,” Timeout, 13 December 2021, https://www.timeout.com/singapore/news/singapore-dance-theatre-unveils-its-new-name-121321. ↩

-

“Singapore Ballet 2023 Season,” Ballet Herald, 17 December 2022, https://www.balletherald.com/singapore-ballet-2023-season/. ↩