Restoring Classic Films from Asia

Besides restoring made-in-Singapore films, the Asian Film Archive is also involved in the preservation of other seminal Asian works.

By Chew Tee Pao

Since it was established about two decades ago, the Asian Film Archive (AFA) has restored many films connected to Singapore. These include classic titles from the golden age of Malay cinema such as K.M. Basker’s Patah Hati (1952) and Hussein Haniff’s Dang Anom (1962) to more recent Singapore movies like Mee Pok Man (1995) and Money No Enough (1998). However, as the name of the organisation implies, the AFA has also been active in restoring films from around the region. In 2005, when the archive was founded, director Mike De Leon became the first Filipino filmmaker to donate his works to the AFA for preservation.

An eminent filmmaker of the second golden age of Philippine cinema from the 1970s to early 1980s, De Leon sent his films to the AFA in a variety of film formats that included 35 mm original picture and sound negatives, and his own collection of surviving 35 mm exhibition prints.

Mike De Leon’s Batch ’81

In 2014, ABS-CBN Corporation, the largest media conglomerate of the Philippines, embarked on the first restorations of De Leon’s filmography beginning with Hindi Nahahati ang Langit (An Indivisible Heaven, 1985) – about two stepsiblings who fall in love – using the negative it acquired. In 2015, ABS-CBN loaned from the AFA the 35 mm original camera and sound negatives of De Leon’s 1980 musical comedy Kakabakaba Ka Ba? (Will Your Heart Beat Faster?) and subsequently the surviving 35 mm release prints of the 1979 Kung Mangarap Ka’t Magising (Moments in a Stolen Dream), a coming-of-age romantic drama, for digitisation and restoration.

Both films were produced by LVN Pictures, one of the biggest film studios of Philippine cinema since its inception in 1938. The LVN studio ceased operations in 2005, and ABS-CBN Corporation acquired the assets to maintain the legacy of LVN Pictures and the films it made. The rights to De Leon’s other works belonged to either the director or multiple parties.

Considering and navigating the legal and copyright issues are essential in preparing for any film restoration. With the approval and support from the film’s executive producer Marichu Vera-Perez Maceda in 2016, the AFA assessed and determined the urgency to digitise and restore De Leon’s 1982 critically acclaimed Alpha Kappa Omega Batch ’81 (also known as Batch ’81 or ΑΚΩ 81).

Produced at a time of great political unrest and turmoil during the period of martial law in the Philippines (1972–86) under then President Ferdinand Marcos, the psychological film chronicles fraternity Alpha Kappa Omega’s brutal initiation of new members as seen through the eyes of university student Sid Lucero. The film has been often referred to as one of the greatest Filipino films of all time and a metaphor for the Philippines under the Marcos regime.1

With the original camera and sound negatives and a surviving positive print that had been preserved by the AFA since 2005, the film became the archive’s first restoration of a Filipino title. The original camera and sound negatives of Batch ’81 exhibited critical signs of “vinegar syndrome”, where films become brittle, shrink and emit an acidic odour. It had developed haloes and mould, with major green-hued defects on the emulsion. As a result, parts of the picture negative were unusable and the laboratory – L’Immagine Ritrovata in Bologna, Italy – overseeing the restoration had to integrate shots from the positive print during the process of digital restoration.

With the assistance of a post-production company in Manila, De Leon and the film’s original cinematographer, Rody Lacap, supervised the colour grading using the restored scans. The colour-corrected restored scans were then returned to L’Immagine Ritrovata to produce new negatives of the film. The entire restoration, including generating new 35 mm negatives and print, took nearly a year.

In September 2017, the restored Batch ’81 premiered at the Venice Classics section of the 74th Venice International Film Festival. I had the privilege of attending the festival for the first time and read an opening statement from Mike De Leon to the audience. After Venice, the film screened in Manila in October 2017 as the closing film of the QCinema Film Festival.2 In Singapore, the film was shown at the AFA’s annual restored film series, “Asian Restored Classics”, on 30 August 2018.3

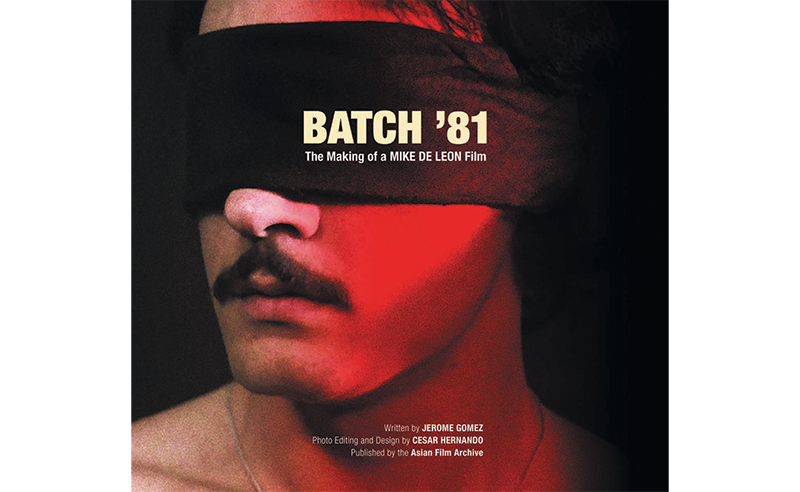

Launched in conjunction with the film’s restoration, the AFA published Batch ’81: The Making of a Mike De Leon Film to document the history behind the making of the film.4 The publication was made possible with De Leon’s collection of related materials such as photographs and memorabilia, recollections from the director, his creative team, and the actors who played both pivotal and minor roles in the film.

Garin Nugroho’s Surat Untuk Bidadari

In 2019, as the work to restore They Call Her… Cleopatra Wong got underway,5 the AFA was tackling another challenging restoration of an Indonesian film, Surat Untuk Bidadari (Letter to an Angel, 1994). This is the second feature film of director Garin Nugroho, who is considered a pioneer for a new generation of Indonesian filmmakers of the 1990s.

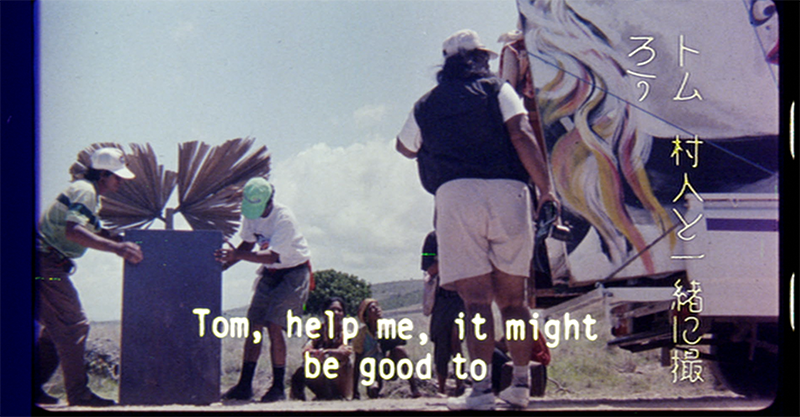

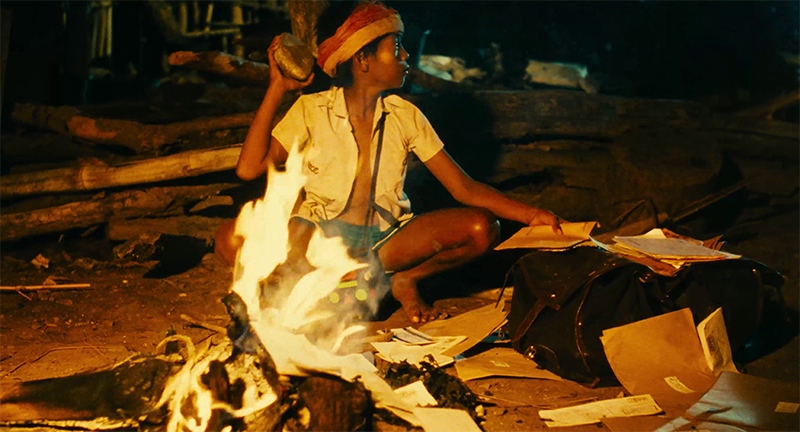

The film is about Lewa, a boy who believes in an angel that looks after the earth. Having lost his mother early, Lewa writes to the angel for answers, but is frustrated by the lack of reply. The film is notable for being the first to be shot on Sumba, one of the islands in the Nusa Tenggara, stretching from Bali to Timor. It was one of the last bastions of pre-Hindu animism. Adapting a story banned under the administration of Suharto during the New Order (1966–98), the film depicts a traditional Indonesian society at odds with modernity.6

The original film was never commercially released within the country but won critical acclaim overseas, including the Gold Prize at the Young Cinema Competition of the 1994 Tokyo International Film Festival and the Golden Charybdis (Best Feature Film) at the 1994 Taormina International Film Festival. It was screened at the Oldham Theatre on 8 September 2019 as part of the 2019 edition of “Asian Restored Classics”.7

A landmark work in Indonesian cinema, Surat Untuk Bidadari has been an inspiration to newer generations of Indonesian filmmakers. Most notably, its screenplay provided Mouly Surya, another Indonesian director, with the premise for her widely acclaimed hit, Marlina the Murderer in Four Acts (2017), which premiered in the Directors’ Fortnight section of the 2017 Cannes Film Festival.8

In July 2016, I attended the 9th Biennial Association for Southeast Asian Cinemas Conference in Kuala Lumpur and had the opportunity to meet Garin Nugroho, who was a panellist at the conference. He shared with me that after the fall of the Suharto administration in 1998, the film laboratories that were associated with the administration closed and most of the original negatives and prints, including those of his early works, were either destroyed or lost.

There was only a single 35 mm print of Surat Untuk Bidadari residing at the Sinematek Indonesia, a film archive based in Jakarta, but it was a censored version. From the book, Indonesian Cinema After the New Order: Going Mainstream, I learnt that since the 1970s, the Suharto administration “[had taken] an active role in controlling film production and content through new laws and regulations”, and “film producers were known to submit a version of the film to the censors to be cut, but then played the uncut version in cinemas”.9 It was deduced that the film was such a case, but never got its release.

Before every restoration, it is essential to take stock of all available film elements that can be used. After weeks of investigations, the AFA located a second 35 mm print of Surat Untuk Bidadari residing with the Film and Broadcast media section of The Japan Foundation. It was subsequently ascertained that the print was the very same one screened at the Tokyo International Film Festival in 1994.

It was fortuitous that the second print was sent via a diplomatic bag through the Japan Embassy in Jakarta in 1994. If Garin had the print exported on his own, it would have needed prior clearance from the Indonesian government or would have been confiscated at customs.

“The film was made in 1994 in the era of Suharto, [an] era full of control and censor. The filmmaker cannot send their film by themselves to the foreign country [international film festival]. If the filmmaker [sends it himself], it needs permission from the government with many requirements and [would be] complicated. So this film was sent with a diplomatic bag from the embassy,” said Garin.10

Garin decided not to bring the film back to Indonesia for fear of interrogation by the Indonesian government. This was in line with the account in Indonesian Cinema After the New Order of how during the New Order, “titles exported overseas often riled bureaucrats because they did not pass domestic censorship beforehand, thus risking a negative impression of Indonesia overseas”.11

Both the 35 mm prints from Sinematek Indonesia and The Japan Foundation were sent to Éclair Cinema (now Éclair Classics), a film restorationlaboratory in France, for comparison, and it was confirmed that the one from The Japan Foundation was a complete version of the film. The latter was therefore used as a secondary source to the Indonesian print as it contained burnt-in English and Japanese subtitles.

The print from Sinematek Indonesia was affected by dirt and shrinkage and had numerous thick scratches on the emulsion and base of the material. Damage from folds, torn frames and broken perforations were uncovered during inspection. Many of the splices made with tape had deteriorated and had to be repaired to smoothen the process of digitisation. A total of 14 shots and 4,500 frames (approximately 3 minutes and 7 seconds) were also missing from the Indonesian print and had to be reconstructed using the Japanese print as a reference. Numerous scenes and shots on the Indonesian printthat were either shortened or removed from the original suggest that images depicting discord and insubordination were deliberately removed.

The restoration of Surat Untuk Bidadari took about six months. Fortunately, Garin was available to catch a work-in-progress preview of the restoration at the Oldham Theatre at the National Archives of Singapore, where the AFA holds its regular screenings. Having not seen the film play on a big screen in over 20 years, he reminisced about the making of the film and shared anecdotes as we watched the film.

Garin told me the film serves as capsule for a time that cannot be revisited and re-experienced since Sumba has become a hotspot for local tourists in the last decade. He was appreciative that the film can now be seen as close to its original form by new audiences.12

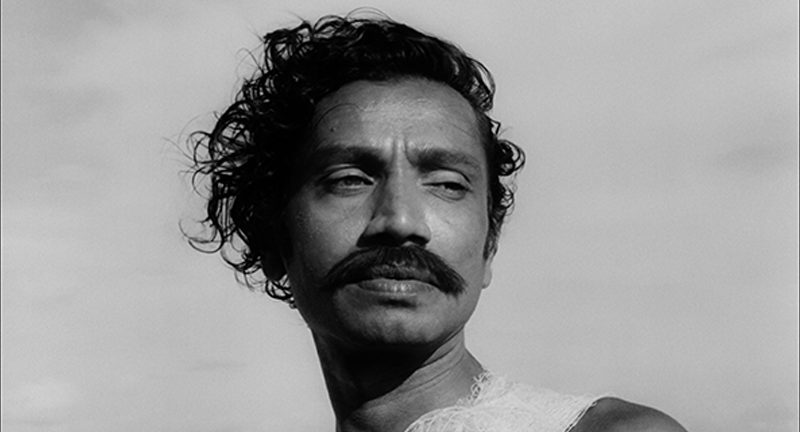

Dharmasena Pathiraja’s Bambaru Avith

Nearly two decades before Garin Nugroho began his film career in Indonesia, there was Dharmasena Pathiraja (1943–2018), a pioneer of Sri Lankan cinema’s “second revolution” in the 1970s. Having made a total of nine feature films, Pathiraja is often referred to as the “rebel with a cause” for his films that served as social commentaries on the prevailing socio-economic and political realities in Sri Lanka. The director passed away at the age of 74 on 28 January 2018.

The AFA’s first encounter with the works of Pathiraja was serendipitous. In 2017, the AFA was alerted to the existence of the 35 mm reels of three films: Ponmani (Younger Sister, 1977), Bambaru Avith (The Wasps Are Here, 1978) and Soldadu Unnahe (Old Soldier, 1981) that were found languishing below a stairwell of a local institution, which had collected the films years ago but was unable to care for them. These films, which have severely deteriorated, turned out to be among Pathiraja’s seminal works as these are among the filmmaker’s earliest films that were screened and won awards outside of Sri Lanka.13

Set in the northern city of Jaffna, Pathiraja’s only Tamil-language film, Ponmani, traces the fortunes and concerns of an economically depleted upper caste, lower middle-class family. Ponmani, the youngest daughter in the family has to wait until the marriage of the middle daughter, Saraoja, before she can escape from her life in the home. She falls in love with a boy from a lower fisherman caste but learns that her family has no money to pay for Saraoja’s dowry.

Bambaru Avith tells the story of the clash between local fishermen in Kalpitiya, a fishing village in Sri Lanka, and a group of urban entrepreneurs who arrived at the village. The city folk, headed by Victor, bring a business ethic of their own: capitalistic tendencies that anger Anton, the patriarch of the village. When Victor gets involved with a local village girl, tensions arise culminating in a series of violent events.

In Soldadu Unnahe, a World War II veteran, a prostitute, her thieving pimp and an alcoholic, who are distinctly marginalised in society, take refuge at the base of a tree as their asylum from the rousing celebrations and spectacle of Sri Lanka’s Independence Day.

Over the next few months, my team members and I took turns inspecting every reel of the three films by carefully unwinding each reel by hand. All the reels were found to be suffering from varying degrees of “vinegar syndrome” and mould infection. Physically, the reels seemed as though they had been dunked or lathered in heavy black grease. Among the film elements, there were many reels that we had to halt inspection as the emulsion of each film reel was stuck together. Unwinding it any further without the right equipment and chemical intervention could cause additional damage or smear the images. Of the three rescued titles, we could only unwind the reels of Bambaru Avith, and it became clear that this film was the most complete and in a sufficiently stable condition.

With the support of Pathiraja’s family, the AFA decided to embark on the restoration of the film and spent several months trying to locate any other film elements that might have been kept by other archives and institutions. Unfortunately, the search came to naught. It was subsequently verified by the National Film Corporation of Sri Lanka that the 35 mm release print with the AFA is likely the sole surviving copy of the film.

In mid-2019, L’Immagine Ritrovata was appointed to restore the film. The laboratory applied an intensive desiccant over the reels to reduce the stickiness and to improve the print condition so that repair work could be conducted to ensure that the film could mechanically withstand the digitisation process. After weeks of treatment, the film could finally be unwound and repair work could proceed.

Since there were no other film elements and good image information for comparison, automatic digital restoration tools could not be utilised. This meant that each frame had to be manually processed to remove dust and scratches. Additionally, each image had to be stabilised, de-flickered and colour-corrected. Audio restorers also had to eliminate and reduce clicks, crackles and bumps within the soundtrack to smoothen excessive noise and balance the overall tone. The restoration of the film took almost an entire year.

As part of the AFA’s preservation workflow, the raw and restored digital scans, a new 35 mm picture and sound negatives as well as a new positive print of the restored version of Bambaru Avith were produced. The film was selected for the Classics section at the 73rd Cannes Film Festival in 2020, a testament to the masterpiece waiting to be rediscovered, made possible through the successful restoration of the film.14

In 2021, the AFA embarked on the digitisation of the prints of Soldadu Unnahe and Ponmani but sadly the deterioration was so advanced that there was complete loss of images and sound in many parts of the prints. The AFA continues to be in search of surviving film elements of these two films.

With film restoration being an expensive and laborious process, there may not always be funding to restore a film. In the meantime, there is a greater number of films that are lost when they are not being preserved. My hope is that more filmmakers will realise the importance of entrusting and preserving their films with a film archive as soon as possible, and not wait until the films have deteriorated to a point that only restoration can help salvage them, if these are even salvageable at all. This is how we have lost many valuable classic films.

Chew Tee Pao is Senior Archivist at the Asian Film Archive (AFA). Since 2014, he has overseen the restoration of more than 30 films from the AFA collection.

Chew Tee Pao is Senior Archivist at the Asian Film Archive (AFA). Since 2014, he has overseen the restoration of more than 30 films from the AFA collection.Notes

-

“Batch ’81 (1982),” Asian Film Archive, last accessed 25 August 2023, https://www.asianfilmarchive.org/event-calendar/batch-81-1982/. ↩

-

“Restored ‘Batch ’81’ to Close This Year’s QCinema Festival,” Interaksyon, 5 October 2017, https://interaksyon.philstar.com/entertainment/2017/10/05/101766/restored-batch-81-to-close-this-years-qcinema-festival/. ↩

-

“Asian Restored Classics (2018),” Asian Film Archive, last accessed 25 August 2023, https://asianfilmarchive.org/event-calendar/asian-restored-classics-2018/. ↩

-

Jerome Gomez, Batch ’81: The Making of a Mike De Leon Film (Singapore: Asian Film Archive, 2017). (From PublicationSG) ↩

-

For the restoration process, see Chew Tee Pao, “Money No Enough, Passion Needed Too: Restoring Classic Singaporean Films,” BiblioAsia 19, no. 2 (July–September 2023): 20–27. ↩

-

“Letter to an Angel (Surat Untuk Bidadari) (1994),” Asian Film Archive, last accessed 25 August 2023, https://www.asianfilmarchive.org/event-calendar/letter-to-an-angel-1994/. ↩

-

“Letter to an Angel (Surat Untuk Bidadari) (1994).” ↩

-

Liz Shackleton, “Mouly Surya on Cannes title ‘Marlina the Murderer in Four Acts’,” Screen Daily, 24 May 2017, https://www.screendaily.com/features/mouly-surya-on-cannes-title-marlina-the-murderer-in-four-acts/5118425.article. ↩

-

Thomas Barker, Indonesian Cinema After the New Order: Going Mainstream (Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, 2019), 39, 41. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSEA 792.4309598 BAR) ↩

-

Garin Nugroho, email correspondence, 23 July 2019. ↩

-

Barker, Indonesian Cinema After the New Order: Going Mainstream, 41. ↩

-

Garin Nugroho, post-screening discussion, 8 September 2019. ↩

-

Chew Tee Pao, “Restoring Bambaru Avith (The Wasps Are Here),” Asian Film Archive, 16 June 2021, https://asianfilmarchive.org/restoring-bambaru-avith-the-wasps-are-here/. ↩

-

Susitha Fernando, “‘Bambaru Avith’ in Cannes Classics,” The Sunday Times, 2 August 2020, https://www.sundaytimes.lk/200802/magazine/bambaru-avith-in-cannes-classics-410914.html. ↩