Journey of Faith: Haj Pilgrimage in the Malay Archipelago Before the 20th Century

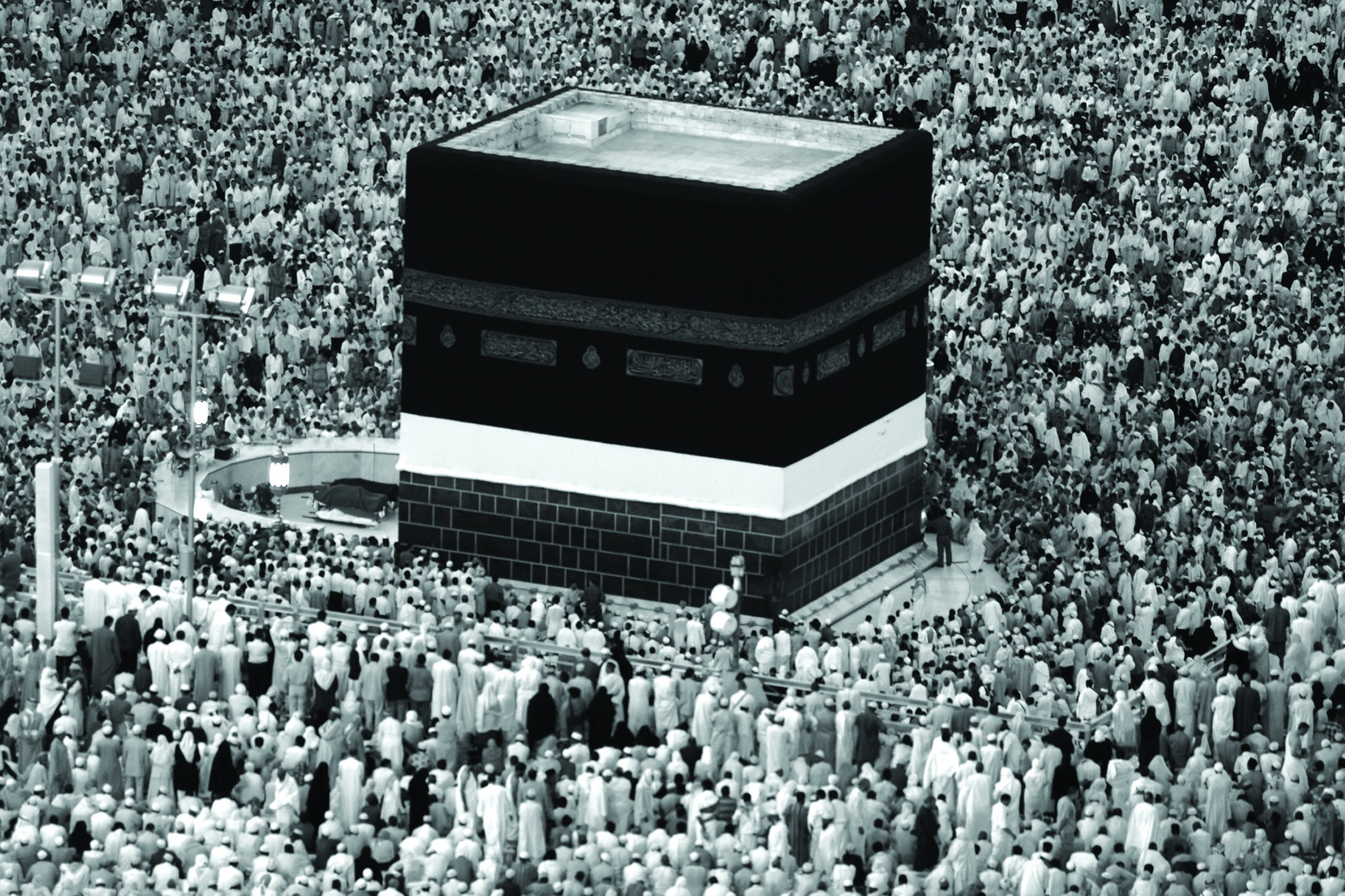

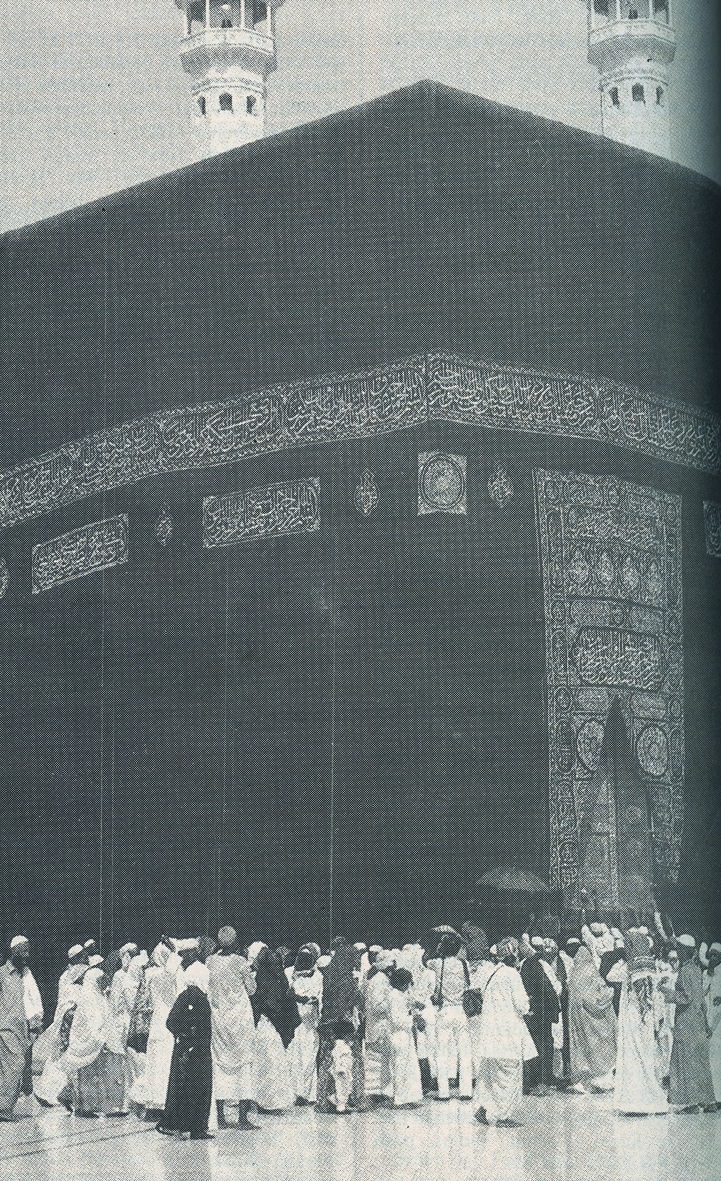

Making the journey to Mecca to fulfil the obligation of the Haj is a long and cherished ambition for most Muslims. In heeding the call of the Ka’bah (House of God) in Mecca, where all Muslims turned to in their prayers, the Haj is not for the faint-hearted or the ill-prepared.

Making the journey to Mecca to fulfil the obligation of the Haj is a long and cherished ambition for most Muslims. In heeding the call of the Ka’bah (House of God) in Mecca, where all Muslims turn to in their prayers, the Haj is not for the faint-hearted or the ill-prepared. In Haj, the pursuit of spiritual upliftment transcends worldly wants and often requires stoicism in the face of hardships. During travels in strange Arab lands and in close company of multitudes of strangers, hardships are never few. As an obligation, in fact, the Haj is not demanded on those who cannot canvass the strength and earnings to leave their routines and family dependants behind in order to complete the intense Haj rituals.

For far-flung devotees such as Muslims in Southeast Asia, just traversing parts of the globe to reach Mecca was once a severe test to their mettle. Today, because of advanced transportation, flights from anywhere in the world have diminished the distance to Mecca, making the trip to the Holy Land bearable. Surviving the journey to Mecca is almost a certainty and forms the least of the pilgrims’ worries. A return passage to their homeland at the end of the Haj is also guaranteed, as most pilgrims would have booked a two-way ticket. This was not the practice in the old days, as it was the custom for pilgrims to book a one-way ticket to Jeddah. They booked their ticket home from Jeddah only after they had completed their Haj. In the preflight days, many pilgrims, often due the treachery of their motowwaf (local pilgrim guides), found themselves with no money for their return passage. In one instance, in 1897, the British Consul in Jeddah had to assist 106 pilgrims to make it back to home. There were others however who were not so lucky. They became victims to shipping agents’ manipulation to secure cheap labour. Just before the turn of the 20th century, in what was to become a big scandal in Singapore, the colonial government in Singapore uncovered a syndicate, which cunningly offered destitute pilgrims an advance on their return fares in exchange for the pilgrims’ agreement to work in the shipping agent’s plantations. The debt-bondage arrangement that ensued led to the recruitment of many plantation coolies from the rank of these destitute pilgrims. They were unable to free themselves even after reaching the maximum period of their tenure.

For pilgrims in Singapore, Malaysia and Indonesia (and for the most part of the world), hassle-free journeys only came about in the 1970s when flights became regular and affordable. Prior to that, Malay pilgrims travelled to Mecca mainly by sea on sailing ships and later steamers. It would take months to reach the port at Jeddah, where the vessels would congregate and spill their contents.

Convergence of Human Waves

During the first 13 centuries of Islam, to embark for Haj was like attempting to run an endless marathon. The journey could take years, as many pilgrims were poor and had to stop en route to work and save before setting out again. Before the first half of the 19th century, a vast majority of pilgrims took the overland route to Mecca, which proved to be more arduous than the sea route. There were three slow-moving waves of pilgrims entering Mecca during the Haj season. The first arrived by an armada of ships that ploughed the vast Indian Ocean and Arabian Sea from these locations:

a. The sprinkled archipelagos of the East Indies

b. The great inverted triangle of the Indian subcontinent

c. The coast of East Africa and the horn of Africa

The next wave, slower than the first, trotted by foot or on horse/camel caravans, bringing pilgrims from the Middle East and North Africa. Even slower is the last wave, which trudged across Central Africa. Pilgrims on all these waves braved hardships; the adventurous overland folks had to conquer harsh terrains, fought off raids by moving tribes or found themselves just plain lost. For their sea-faring counterparts, the spectre of diseases loomed, or they risked their lives when their boats were overturned by ruthless waves.

In the absence of official statistics before the 19th century, it would not be too inaccurate to estimate that only a conservative number from the Archipelago went on Haj, as many would be discouraged to undertake travel due to the hazardous and protracted nature of the journey. The total number of pilgrims in Mecca before the 19th century was also relatively small to begin with, according to William Facey:1

Historical statistics are few, but travellers’ and officials’ reports indicate widely varying pilgrim numbers. One of the highest was 100,000, recorded in the year 1279. In 1383, some 17,000 pilgrims crossed Sinai in the Egyptian caravan, and in 1503 the Italian traveller di Varthema estimated about 40,000 in the Damascus caravan… In 1831, a British report estimated 120,000 pilgrims in total, about 20,000 of whom arrived at Jiddah by sea from India, Malaya, the Arabian Gulf and the Red Sea ports of Suez, Qusair, Sawakin and elsewhere – and that seems to have been the best year for half a century or more. What is striking is how small overall pilgrim numbers were.

The majority from this small number took the overland route. Ship-going pilgrims who formed the remainder came only from these places: sub-Saharan Africa, India and Malaysia. Since Malay pilgrims were represented only in the sea travellers group, the Archipelago’s overall contribution to the already small number of pilgrims was hence limited.

Haj in Malay Traditional Text

Early records of Haj pilgrimage from the Malay Archipelago showed that pilgrimage was a private enterprise and confined to certain classes of individuals. Before the commercialisation of the Haj in the late 19th century that enabled en masse pilgrimage to Mecca, Haj incumbents either individually or in small groups made their own arrangements for Mecca. Those who went were usually men of some standing in the community – either they had the resources, or they had attained a relatively high level of Islamic education.

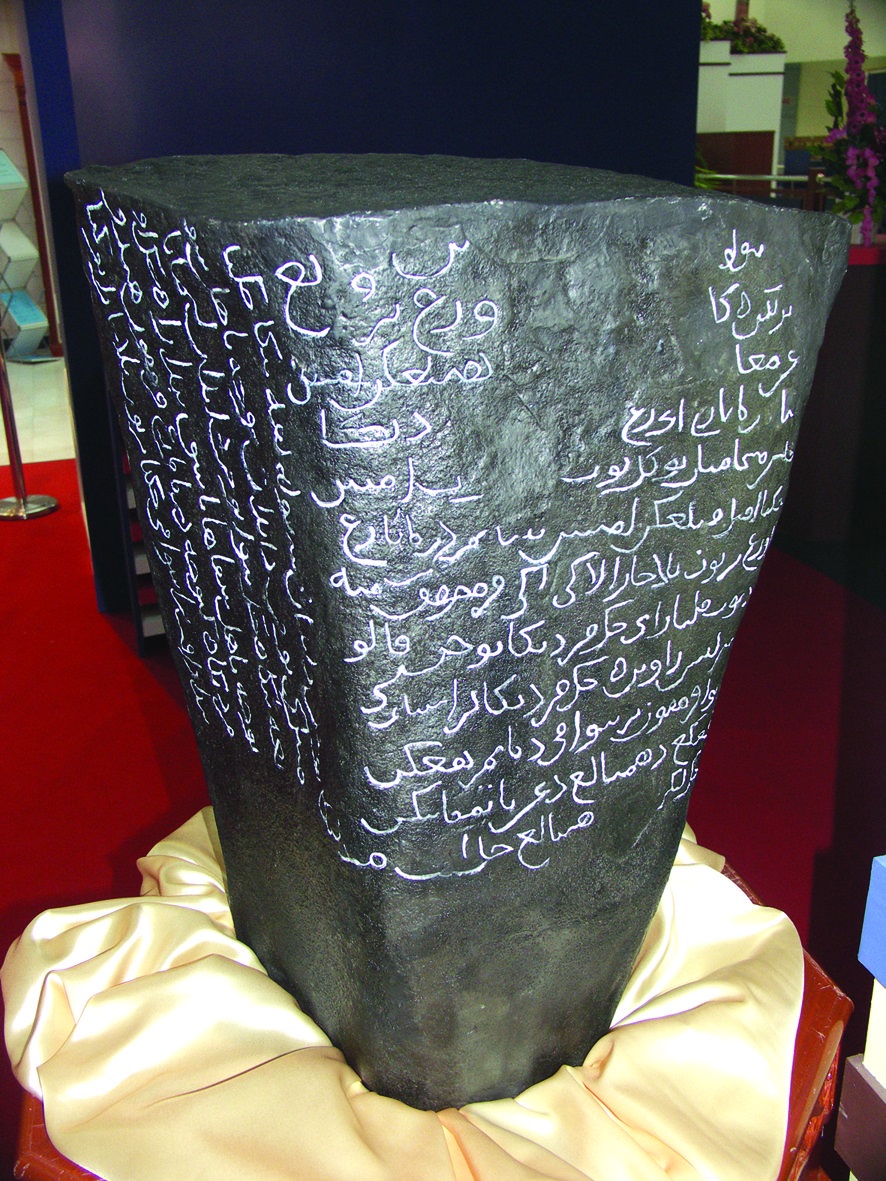

Both in Malaysia and Indonesia, the identity and period of the first Haj pilgrimage are not known, although it is likely they occurred within the backdrop of the genesis of Islam in this region. While there are more than one theory on how and when Islam came into the region, the founding of Islamic kingdoms in the Archipelago has had the effect of heightening awareness and aspirations towards the Haj. By the late 13th century, Islam had spread to Southeast Asia. The discovery of the Trengganu Stone (Batu Bersurat), dated 1303 with Arabic inscriptions in 1887 at Kuala Berang, Trengganu, attested to the influence of Islam by this date. With the founding of the Kingdom of Malacca around 1400 and the conversion of its founder, Parameswara, by 1414, Islam penetrated a major Malay state ideology and polity. In Indonesia, the earliest known conversion to Islam by a local ruler occurred in Aceh, North Sumatra, in the late 13th century. By the middle of the 17th century, the Muslim kings in Java were more than anxious to capitalise on Haj to legitimise their kingdoms. By the middle of 17th century, it was not only the Islam phenomenon that had taken over the kingdoms in Java, but also their kings were anxiously looking for Islamic symbols to legitmise their kingdoms and many capitalised on Haj.

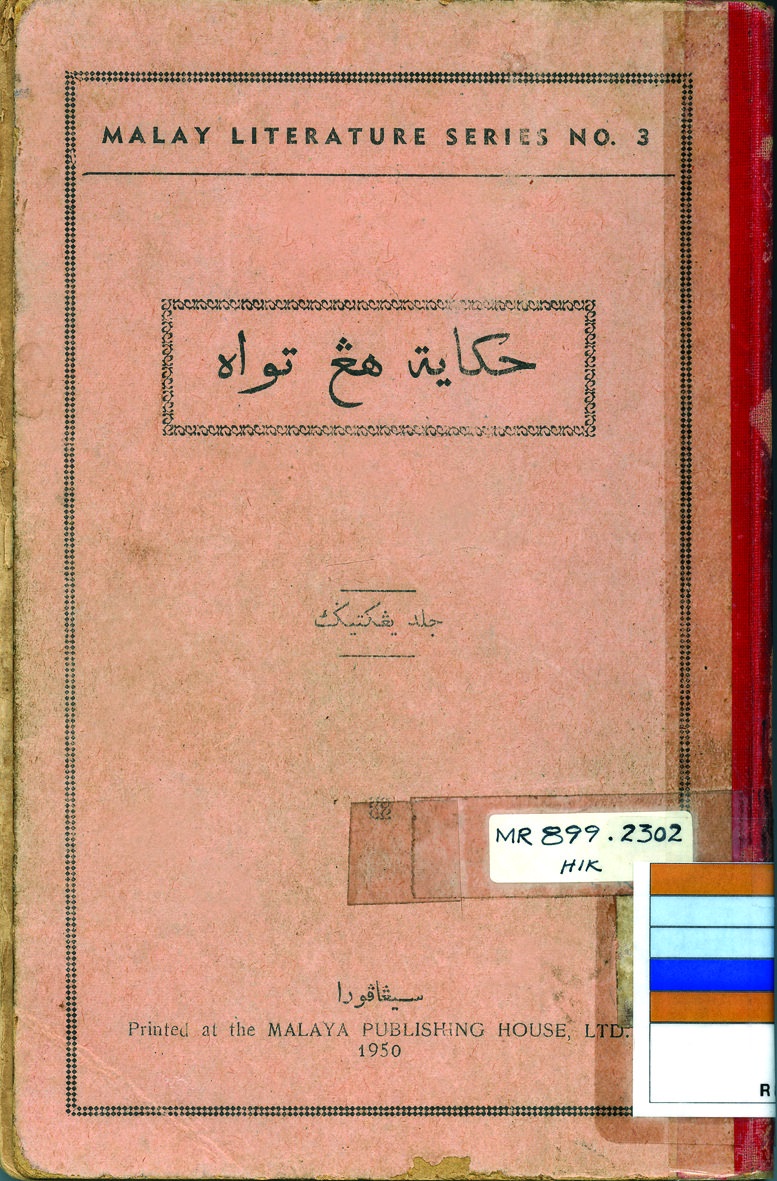

Legends and epics dominate the early literature on Haj in this region, and while they present a continuum between legend and fact, this literature is still a good source to speculate who the Haj pilgrims were before the 19th century. The Malay hikayat contain some of the earliest instances of Haj in this region. Hikayat Hang Tuah (possibly first written in the 16th century) records a Haj pilgrimage in the 15th century, undertaken by Hang Tuah, a great Malay warrior. While the authenticity of both this epic and the legendary hero is debatable, the detailed account of his deeds in the Holy Land is not too far from the rituals preached to Haj pilgrims. On this basis, there were claims that Hang Tuah’s pilgrimage in the 15th century leans more towards fact than fiction.

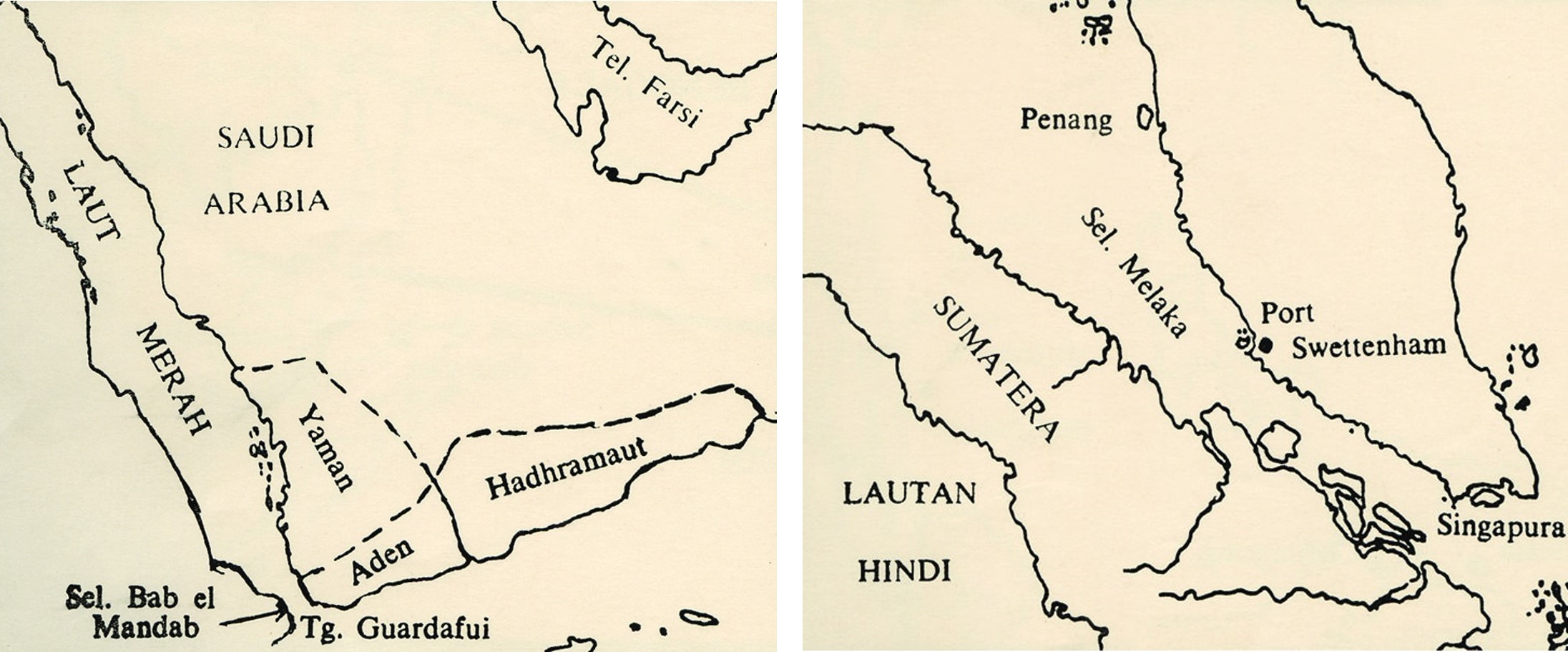

Authenticity aside, the Haj journey in Hikayat Hang Tuah is useful for its insights on the route, ports of call, places traversed and the modes of transportation. The Hikayat records Hang Tuah as taking more than two months to reach Jeddah, leading a fleet of 42 ships and bringing with him 1,600 followers and 16 officials. The route he took is below:

a. From Malacca to Aceh – 5 days and 5 nights

b. From Aceh to Pulau Dewa – 10 days

c. From Pulau Dewa to Bab Mokha (Mocha is in Yemen. The journey from Pulau Dewa to Jeddah took two months.)

According to_Hikayat Hang Tuah_, Hang Tuah’s pilgrimage was coincidental, for his ultimate quest was the quasi-mythical empire of Rome, and his imperial mission was to establish ties with the King of Rome and purchase weaponry. On his way to Rome, Hang Tuah called at Mecca just at the time when the Haj season was about to begin, and so he joined the pilgrims there for Haj. This is unlike other Islamic kingdoms in Indonesia whose kings consciously planned missions to Mecca with the desire to be conferred the title “Sultan” by the Great Sheriff (Syarif Besar). Their actions could be prompted by the belief that only the Great Sheriff, with his control over the holy cities of Mecca and Medina, had the spiritual authority to bestow supernatural aura and power on Islamic kingdoms, although there was no such tradition in Mecca. In 1630s, competition between the King of Banten and the King of Mataram led each of the kingdoms to send holy missions to Mecca. The mission from Banten returned in 1626, while that from Mataram arrived home in 1641.

The King of Makassar also sought the title of Sultan from the Sheriff of Mecca. It is more than likely that the individuals in these missions, following Hang Tuah’s example, would take the opportunity of their presence in Mecca to perform Haj.

The politicisation of Haj in the pursuit of supernatural kingdoms led the kings themselves to make their journey to Mecca. In 1674, the first Banten royalty, Abdul Qahar, who was the son of Banten king Sultan Ageng Tirtayasa, went on Haj. For his spiritual feat, he was known as Sultan Haji (Haji King). The legends Sejarah Banten (written in the second half of the 17th century) and Hikayat Hasanuddin (written around 1700) also record the Haj pilgrimage of the founder of the Islamic dynasty in Banten, Sunan Gunung Jati. Their journey to Haj, though, is couched in supernatural elements.

Haj also crept into the Sundanese literary tradition. Carita Parahyangan, a Sunda text on the history of the Galuh kingdom written around 1580, records the Haj pilgrimage of Bratalegawa, the son of the King of Galuh. According to this volume, Bratalegawa was the first person to convert to Islam in Sunda. Bratalegawa chose to lead a trader’s life and sailed to as far as Arabia. He went on Haj in the 14th century. As the first person in Galuh to complete the Haj, he was also known as Haji Purwa.

Outside the realm of legends, the honour of the earliest Haj pilgrimage reportedly rests with the rulers of Malacca. Tome Pires reported that during Sultan Mansur Syah’s reign (the sixth king of Malacca who ruled from 1456 to 1477), the Malaccan king almost left the Malay shores for Jeddah, having chartered a ship from Pegu and Jawa as part of his preparations. But his deteriorating health put a stop to his pilgrimage, notwithstanding the large funds and followers he had set aside. His son who succeeded him, Sultan Alauddin Riayat Shah (1477–88), had supposedly swore to realise his father’s Haj ambition. By this promise, scholars and historians in Malaysia concluded that Sultan Alauddin himself had gone for Haj. This is because in Islam, a living person would have to complete his own Haj before he could carry out the Haj on the wishes and behalf of another person. Although Sultan Alauddin’s Haj has not been verified by written records, the Islamic climate in Malacca by that time, with the probable presence of pious men and religious teachers, would have made it conducive for Sultan Alauddin to go on Haj.2

Of Haj and Learned Men

Real data on Haj pilgrims right until the end of the 19th century remains sketchy. In the 17th century, from Indonesia, a few names have been identified. Syaikh Yusuf Makassar left Indonesia for Arabia in 1644 for Haj and scholarly pursuit and returned only in 1670. Syaikh Yusuf not only became a religious leader on his comeback, but also acted as political advisor to Sultan Ageng Tirtayasa in Banten. Another is ‘Abd al-Ra’uf al-Sinkili who stayed for years in Mecca and Medina to deepen his religious knowledge and later became a man of high standing in Aceh.3

In the 13th century, speculations about Haj pilgrims focused on personalities whose scholarly passion and wandering spirit were believed to have inspired them to go to Mecca. Two such personalities are Sultan Muhammad Jiwa Zainal Abidin II of Kedah (1710–60) and Syeikh Abdul Jal ii alMahdani. Their combined encounters with Sumatra, Java and India, and close network with Jambi and Indian shipowners allowed them to venture far. Sultan Muhammad’s return to Kedah from India after six years gave rise to the suggestion that during this period, he did make his Haj together with Syeikh Jalil. Syeikh Jalil had two sons whom he sent to Mecca via sailing ships and who became Meccan residents for several years. In 1772, an Indonesian religious leader who resided in Mecca wrote to Sultan Hemengkubuwono I to recommend appointments for two new Hajis who had recently come back.

Of Haj and Hardships

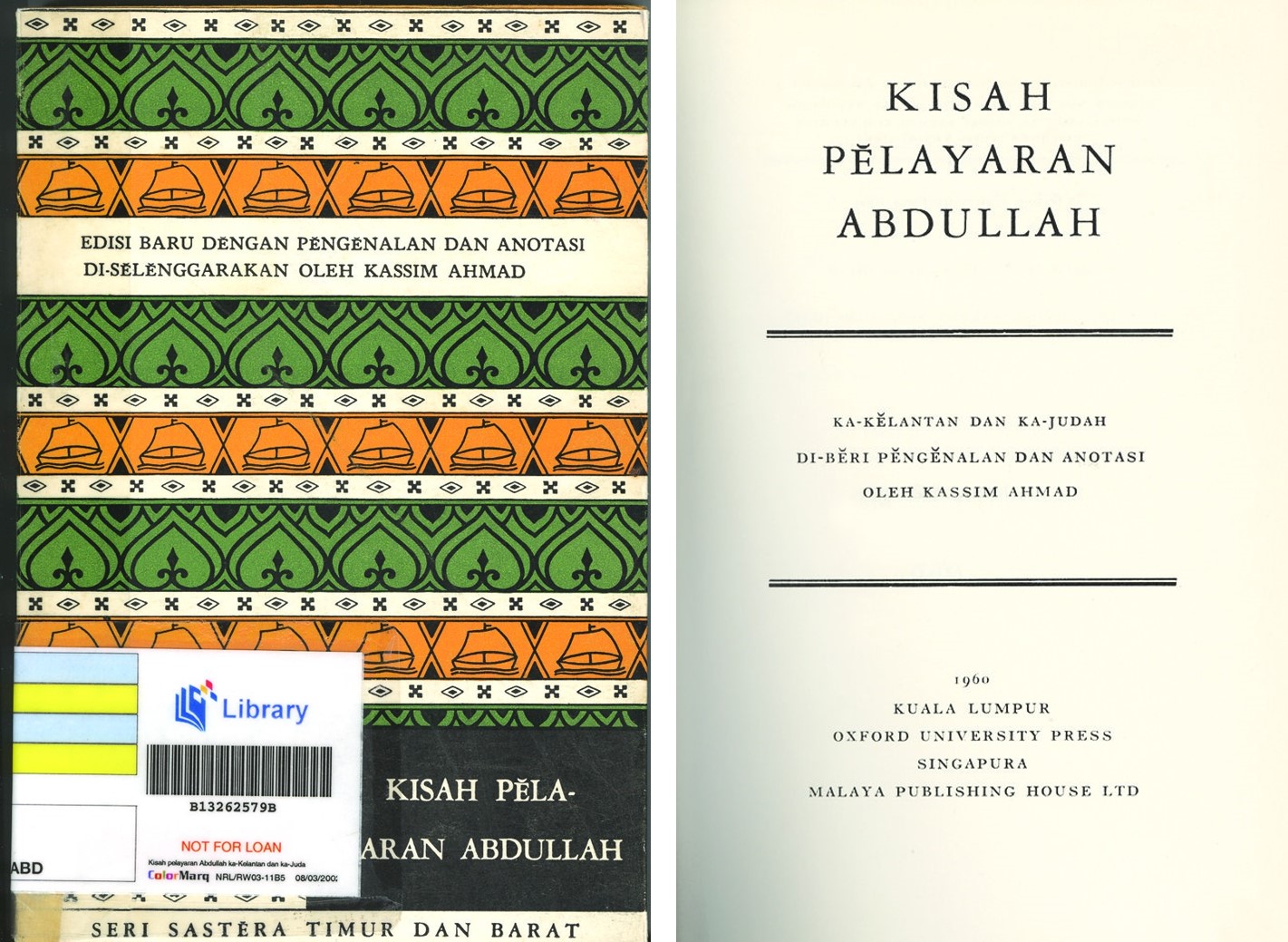

More substantial factual accounts about Haj pilgrimage in the Malay Archipelago started to appear in the 19th century. According to Michael Laffan in Islamic Nationhood and Colonial Indonesia, the first actualised account that mentions journey to Mecca is Munshi Abdullah’s Kisah Pelayaran Abdullah (The Story of Abdullah’s Voyage). Munshi Abdullah, whose literary contributions had earned him the title the father of modern Malay literature, made his journey in 1854.

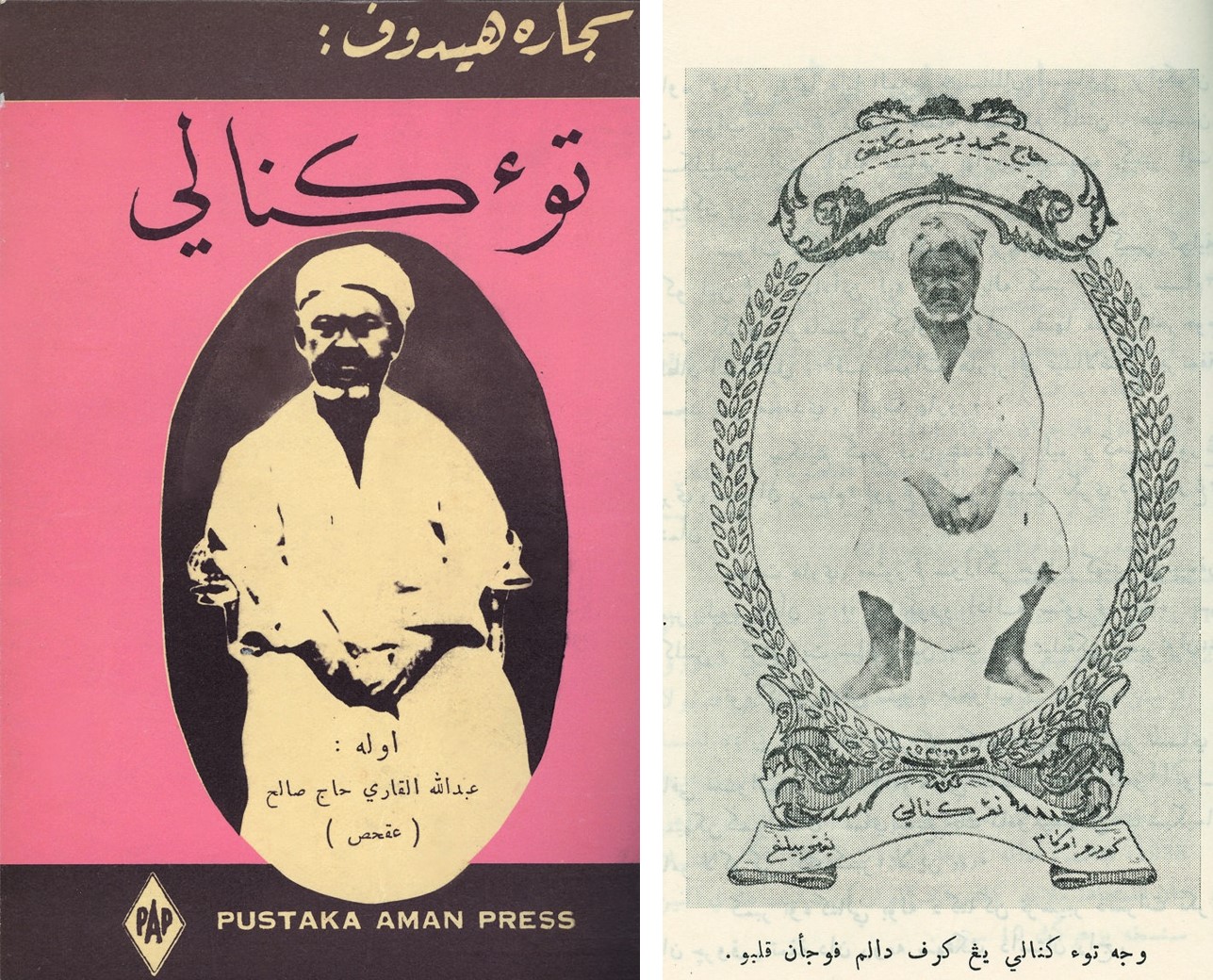

His Haj account stopped shortly before his death in Jeddah. There is also information that points to an even earlier Haj pilgrimage, made by Sayyid Muhammad bin Zainal al ldrus, a Trengganu ulama (religious leader) who is known as the father of Trengganu’s literature. Sayyid Muhammad went to Mecca around 1815 at the age of 20 and spent several years there pursuing his studies. Yet another account in the 19th century relates the story of Muhammad Yusof bin Ahmad, better known as Tok Kenali Kelantan, who went to Mecca in 1886 at the age of 18. An account of his life is found in Sejarah hidup To’ Kenali (The Life of To’ Kenali).

Two of these intellectuals, Munshi Abdullah and Tok Kenali, described a Haj journey that departed from the pompous fleet of ships and entourage-full sailing found in Hikayat Hang Tuah and even Sultan Mansur’s Haj preparations. They wrote of hardships and gave readers a more realistic version of Haj, as if to warn them of its mental and physical exertions.4 Munshi Abdullah drew up a will before he left, accepting the fact that he might not survive the Haj.

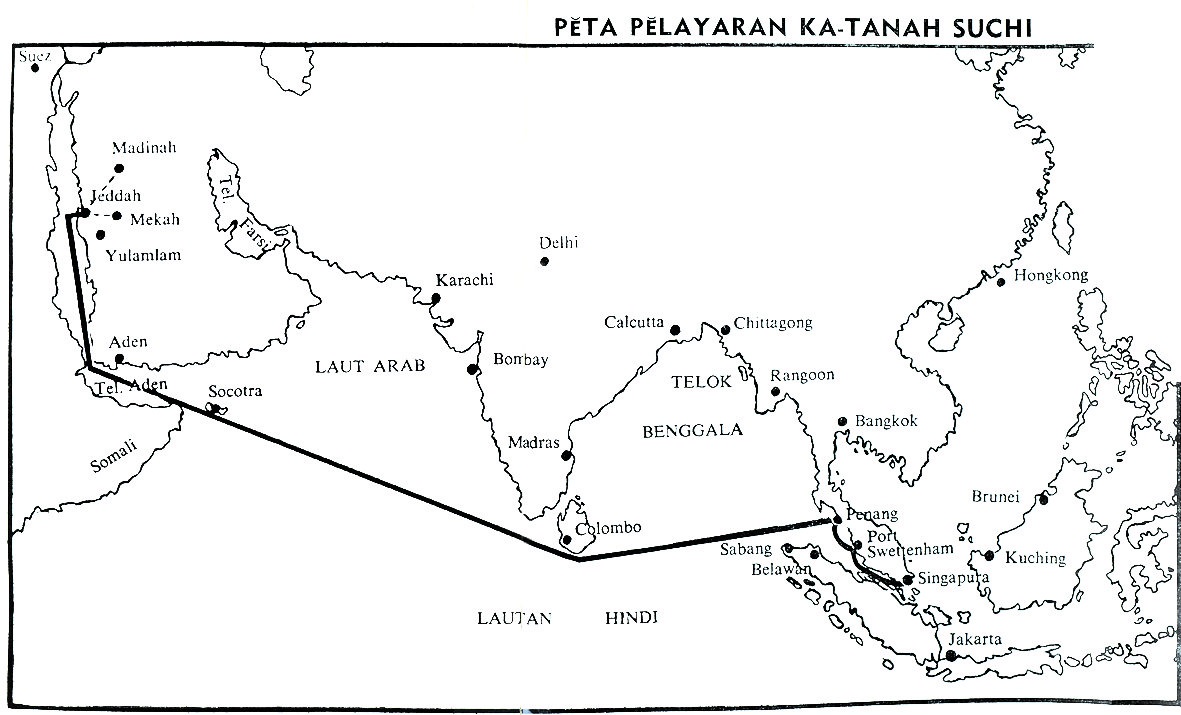

In the actualised accounts, we learn of the many stops Haj pilgrims had to make. The pilgrims also waited for ships, which in turn waited for the right winds to depart. In the days of sailing ships, the Indian Ocean and the lands along its coast lay in wait for the “trade wind”. The phrase “trade wind” is ancient and is derived from an old use of the word “trade” to mean a fixed track. In navigation, it refers to any wind that follows a predictable course. As such winds are instrumental to merchant ships making long ocean voyages, the term evolved to mean in the 18th century as winds that favour trade. In the Indian Ocean, the monsoons are the famous trade winds. They are particularly beneficial to long-distance merchants, because they change direction at different seasons of the year. The northeast monsoon blows from October to March and the southwest monsoon from April to September. As the change in the monsoon winds take months, traders and pilgrims alike had to stay in the various ports of call for the right wind to carry them to their next stop.

The dependence of Haj pilgrims on trading ships during this early period is also described by van Bruinessen in his paper Mencari Ilmu dan Pahala di Tanah Suci: Orang Nusantara Naik Haji (Seeking Knowledge and Merit Indonesians on the Haj). Pilgrims would seek out trading ships to book their passage. As trading ships had their own destination, the pilgrims had to change ships to ensure that they boarded the right ship. Their journey would bring them to various ports in the Archipelago where ships would load up on water and other supplies. The last stop in the Archipelago was Aceh (hence named “Serambi Mekkah” or Verandah of Mecca), and here the pilgrims would wait for ships bound for India. From India, the pilgrims sailed on ships that would bring them to Hadhramaut, Yemen or directly to Jeddah. The perils of sailing for months were many. The ships could sink or be stranded in unknown islands. The pilgrims could be robbed by pirates or even by the ships’ crew. They were vulnerable to diseases while both at sea and on land. Having set foot in Arabia, they could be attacked by the Bedouin tribes. In the Netherlands Indies, between 1853 and 1858, less than half of the pilgrims who went to Mecca made it back safely. This high attrition rate was attributed to mainly dying at sea or being sold as slaves.

For Tok Kenali who went on his pilgrimage in 1886, he could only embark on his journey after securing contributions for the voyages’ fare. His friends in Kelantan gave him $50, and his mother topped it up with $22. The cost of his journey was $100. He set out from Kelantan in an ailing ship that had its sail broken in the middle of the ocean. As a result, a journey that was expected to take three months extended to six months. The delay also depleted the supply of fresh water onboard, and Tok Kenali had to survive on salt-laden seawater. His journey took him along Coromandel Coast and Malabar in India, and then to Ceylon and Sokotora. Sokotora or Pulau Sokotra (Sokotra Island) is located 510 km from the Yemen coast and is the biggest island in the eastern side of the Indian Ocean. Two hundred years ago, its old Port Souk was filled with pilgrim ships mainly from Africa, which stopped there to stock up on water and wood. The pilgrims also obtained other supplies like honey, oil and meat from the people of Sokotra. Upon reaching Mecca, Tok Kenali was desolate with no one to turn to for food and clothing. He survived by serving, from time to time, as a cook for picnics arranged by his friends.

The Voyage of Munshi Abdullah

Munshi Abdullah’s contributions to Singapore history and literature are many. Kisah Pelayaran Abdullah ka-Jiddah (The Voyage of Abdullah to Jeddah) is his lesser-known work, but in view of the dearth of literature on Haj pilgrimage in this early period, this work is indeed invaluable. In his memoir Kisah Pelayaran Abdullah ka-Jiddah, Abdullah was often placed at the end of his tether by the turbulent winds and waves:5

Then at around nine o’clock on Sunday night, the seventh day of the month, the North Wind descended furiously on us. The waves and swells were immense, so much so that our large ship became merely a coconut husk that was being thrashed about by the waves, floating and sinking as it was tossed about in the middle of the sea. All the chests and goods on the left of the ship came crashing to the right, while those on the right came crashing to the left, and this carried on until the break of day.

Abdullah started his voyage to Mecca from Singapore in 1854 on the ship Sabil al-islam owned by Syeikh Abdul Karim. Abdullah made 22 stops before reaching Mecca, in between experiencing four sea storms.

One of the fiercest storm occurred when Abdullah’s ship tried to cross Kep Gamri (Cape Comorin lies at the tip of South India and is infamous for its dangerous waves). As he hung on to his dear life, the thought of death was not far from Abdullah’s mind:6

Oh God! Oh God! Oh God! I can’t even begin to describe how horrendous it was and how tremendous the waves were, only God would know how it felt, it was as if I had wanted to crawl back into my mother’s womb in fright! … All the goods, chests, sleeping-mats and pillows were flung about. Water spewed into the hold and drenched everything completely. Everyone was lost in their thoughts, thinking nothing else but that death was close at hand… In the ship’s hold, the noises made by people vomiting and urinating were indescribable as the sailors kept on hosing down the place… Everyone held fast to the ropes. The sails tore and the ropes broke many times… This continued for two days and three nights, and with God’s pity and help the winds then lessened.

Abdullah also had a chance to board a passenger ship that was transporting Indian pilgrims from Calcutta. The ship was crowded and unbearable:7

By the grace of God, a ship called Atiah Rahman arrived from Calcutta … carried some Bengalis who were making the Haj, totalling one hundred and fifty men, women and children. We went to the ship to secure a passage to Jeddah. The fare for this ship was quite expensive as all the other ships had already sailed away; each person was charged eight Ringgit… God only knew the circumstances aboard the ship and how the crowded mass of people made it so miserable for us who tried to eat, sit or sleep on board (God Willing, all these trials and tribulations will gain us meritorious blessings, for we endured this in the Path of the Righteous).

It is interesting to see the continuity of such conditions onboard pilgrim ships from Abdullah’s time right up to the late 19th–20th century, when steamships ruled the waves. Even with room for more pilgrims on board steamships, serious overcrowding and hygiene problems still haunted Haj pilgrims. Deaths on pilgrim ships en route Mecca were common; during Abdullah’s voyage, more than 20 suffered from chicken pox, and two or three died. Once pilgrims reached the Holy Land, the situation on land was no less chaotic, as according to Abdullah it resembled a “war zone”. Pilgrims’ belongings were piled in haphazard heaps, some smashed, some lost or switched. The taxation of pilgrims’ packages was another source of misery. The tax collector used his discretion, not understood by the pilgrims, to determine which items should be taxed and which should not. No one dared to protest, not even when their packages were ripped apart or ransacked. Abdullah’s writing chests were not spared, and his ink splashed across all his writing papers because too many hands dipped into his chests at the same time.8 The “war zone” scene continued into the late 19th–20th century, and one can only imagine the scale of pandemonium at Port Jeddah, since pilgrims’ arrival in Jeddah in the steamship era had grown by leaps and bounds.

According to Raimy Che-Ross in his translation of Abdullah’s voyage to Mecca, Abdullah did not get to perform his Haj rituals, for he died shortly after reaching Mecca in May 1854. The joy of reaching the Holy Land overwhelmed him that he had forgotten about the hardships he endured during his approximately 100 days’ journey from Singapore. As his heart soared, he composed a poem that became the last words to flow from his pen:9

As I entered into this exalted city

I became oblivious to all the pleasures and joys of this world

It was as if I had acquired Heaven and all that it holds

I uttered a thousand prayers of thanks to the

Most Exalted God

Thus I have forgotten all the hardships and

torments along my journey

For I have yearned and dreamed after the Baitullah

for many months.

Source: Raimy Che-Ross, “Munshi Abdullah’s Voyage to Mecca: A Preliminary Introduction and Annotated Translation,” Indonesia and the Malay World 28, no. 81 (2000): 200.

The incomplete journal of Abdullah’s journey was safely returned to his family in Singapore through one of his companions.

Haj and Arab Shipping in Singapore

The rise of Hadhrami shipping in the Malay Archipelago in the mid-19th century boded well for pilgrims in this region. Hadhrami Arab shippers hailed from Yemen and competed successfully with the Europeans and Chinese in trade and shipping in the Indian Ocean. The Alsagoffs, a prominent Arab family in Singapore, established the firm Alsagoff & Co. in 1848 to conduct trade within the islands of the Archipelago using their own vessels.

In the 1850s, Sayyid Ahmad Alsagoff extended the realm of his family business by starting a profitable business of transporting pilgrims between Southeast Asia and Jeddah. Using Singapore as the base, the Alsagoffs’ position in the pilgrim trade was tremendously strengthened by the Dutch’s restriction on the flow of pilgrims from Indonesia. Pilgrims from the Netherlands Indies during the first half of the 19th century only numbered a few hundreds, as the Dutch imposed a tax on prospective pilgrims. This is to discourage the return of religious fanatics who the Dutch feared would be groomed while performing the Haj and deepening Islamic knowledge in Mecca. Singapore, thus, became the hub of an expanding pilgrim trade from Southeast Asia partly because of this restriction, as many would pass through it by beginning their Haj from Singapore. This tax was removed in 1852.

When steamship arrived in the late half of the 19th century, the Arab shipping merchants capitalised on the speed and capacity of these vessels. By 1871, the Alsagoff-owned Singapore Steamship Company had ferried pilgrims to Jeddah by steamers steered by a European captain and a Chinese hand. Another Arab shipping merchant who ran steamer services for pilgrims was Syed Mohsen AI-Joofree. Towards the end of the 19th century, he was locked in fierce competition with two Dutch steamers for pilgrims. But his business flopped some time before his death in 1894.

Conclusion

By the early 20th century, the Haj had become a competitive business with serious investments by international shipping companies. The waves had been tamed by large steam-powered vessels custom built to combine pilgrim and cargo transport. While the duration to get to Jeddah had improved tremendously, the well-being and safety of Haj pilgrims still lagged behind. The number of pilgrims had swelled to a point that effective sanitation, hygiene, administration and guardianship of pilgrims could not be adequately addressed by purely commercial concerns. The British and Dutch colonial governments introduced regulations to protect Haj pilgrims, but tales of extreme overcrowding in pilgrim ships and of Haj pilgrims getting stranded without a return ticket after being manipulated by shipping agents and brokers continued to be heard. The comfort that Haj pilgrims experience today is a result of decades of reforms by various parties, helped by the advances in transportation. For a journey that is deeply spiritual, the Haj pilgrimage in the Malay Archipelago cannot be divorced from its social and economic dimensions.

Senior Reference Librarian

Lee Kong Chian Reference Library

REFERENCES

Abdullah al-Qari Haji Salleh, Sejarah Hidup To’ Kenali (Kota Bharu: Pustaka Aman Press, 1967). (From National Library, Singapore, call no. Malay RCLOS 920.0595 KEN.A)

Abdullah Munshi, Kisah Pelayaran Abdullah Ka-Kelantan Dan Ka-Judah Di-Beri Pengenalan Dan Anotasi Oleh Kassim Ahmad (Kuala Lumpur: Oxford University Press, 1960). (From National Library, Singapore, call no. Malay RCLOS 959.5 ABD)

Arsip Nasional Republik Indonesia, Biro Perjalanan Haji Di Indonesia Masa Colonial: Agen Herklots Dan Firma Alsegoff & Co (Jakarta: Arsip Nasional Republik Indonesia, 2001), xvi–xxi. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. Malay RSEA 297.352 BIR)

Dadan Wildan, “Orang-Orang Sunda Pertama Yang Naik Haji,” Blog, 14 September 2006.

Dadan Wildan, “Perjumpaan Islam Dengan Tradisi Sunda,” Blog, 26 March 2003.

David W. Tschanz, “Journeys of Faith, Roads to Civilization,” Saudi Aramco World 55, no. 1 (January–February 2004): 3–4.

Edwin Lee, The British as Rulers: Governing Multiracial Singapore 1867–1914 (Singapore: Singapore University Press, 1991), 166–67. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSING 959.57022 LEE-[HIS])

Harun Aminurrashid, Chatetan Ka-Tanah Suchi (Singapura: Pustaka Melayu, 1960). (From National Library, Singapore, call no. Malay RCLOS 297.55 HAR)

Hikayat Hang Tuah (Singapore: Malaya Publishing House, 1950). (From National Library, Singapore, call no. Malay RCLOS 899.28 HIK)

“History of Trade,” Historyworld, accessed 24 August 2006.

Martin van Bruinessen, “Mencari Ilmu Dan Pahala Di Tanah Suci: Orang Nusantara Naik Haji [Seeking knowledge and merit: Indonesians on the haj],” in Indonesia Dan Haji: Empat Karangan, ed. Dick Douwes and N. J. G. Kaptein (Jakarta: INIS, 1997).

Michael Francis Laffan, Islamic Nationhood and Colonial Indonesia: The Umma below the Winds (London: RoutledgeCurzon, 2003). (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSEA 959.8022 LAF)

Muhammad Salleh bin Haji Awang, Haji Di Semenanjung Malaysia: Sejarah Dan Perkembangannya Sejak Tahun 1300–1405H (1896–1985M) (Kuala Terengganu: Syarikat Percetakan Yayasan Islam Terengganu, 1986), 107–37.

Peter Riddell, “Arab Migrants and Islamization in the Malay World during the Colonial Period,” Indonesia and the Malay World 29, no. 84 (2001): 113–28. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSING 959.8 IMW)

Raimy Che-Ross, “Munshi Abdullah’s Voyage to Mecca: A Preliminary Introduction and Annotated Translation,” Indonesia and the Malay World 28, no. 81 (2000): 173–213. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSING 959.8 IMW)

S. M. Amin, “The Pilgrims Progress,” Saudi Aramco World 25, no. 6 (November–December 1974).

Ulrike Freitag, “Arab Merchants in Singapore: Attempt of a Collective Biography,” in Transcending Borders: Arabs, Politics, Trade and Islam in Southeast Asia, ed. Huub de Jonge and Nico Kaptein (Leiden: KITLV Press, 2002), 107–42. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. R 305.8927059 TRA)

William Facey, “Queen of the India Trade,” Saudi Aramco World 56, no. 6 (November–December 2005): 10–16.

William Gervase Clarence-Smith, “The Rise and Fall of Hadhrami Shipping in the Indian Ocean, c.1750–c.1940,” in Ships and the Development of Maritime Technology in the Indian Ocean, ed. David Parkin and Ruth Barnes (London: RoutledgeCurzon, 2002), 227–58.

NOTES

-

Wiliam Facey, “ Queen of the India Trade,” Saudi Aramco World 56, no. 6 (2005), https://archive.aramcoworld.com/issue/200506/queen.of.the.india.trade.htm. ↩

-

Haji di Semenanjung Malaysia: Sejarah dan perkembangannya sejak tahun 1300-1405H (1896-1985M) (Kuala Terengganu: Syarikat Percetakan Yayasan Islam Terengganu, 1986), 115. ↩

-

Haji di Semenanjung Malaysia,107–37; S. M. Amin, “ The Pilgrims Progress ,” Saudi Aramco World 25, no. 6 (1974). ↩

-

Abdullah al-Qari Haji Salleh, Sejarah Hidup To’ Kenali (Kota Bharu: Pustaka Aman Press, 1967) (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RCLOS 920.0595 KEN.A); Raimy Ché-Ross, “Munshi Abdullah’s Voyage to Mecca: A Preliminary Introduction and Annotated Translation,” Indonesia and the Malay World 28, no. 81 (July 2000): 173–213. (From Taylor & Francis Online via NLB’s eResources website) ↩

-

Raimy Che-Ross, “Munshi Abdullah’s Voyage to Mecca,” 186. ↩

-

Raimy Che-Ross, “Munshi Abdullah’s Voyage to Mecca,” 187. ↩

-

Raimy Che-Ross, “Munshi Abdullah’s Voyage to Mecca,” 189. ↩

-

Raimy Che-Ross, “Munshi Abdullah’s Voyage to Mecca,” 173–213. ↩

-

Raimy Che-Ross, “Munshi Abdullah’s Voyage to Mecca,” 200. ↩