The Motor Millions – Towards Our Own Car: Six Years to Assembling Cars in the Peninsula 1963–1968

Traces Malaysia’s attempt to establish a local automotive assembly industry during the exciting years of industrialisation from 1963 to 1968.

Political Backdrop and Automobile Framework in the Early 1960s

In May 1961, then Malaya’s Prime Minister, Tunku Abdul Rahman, suggested the formation of Malaysia – comprising the integration of the three Borneo territories on approximately the same basis as the existing state of the Federation of Malaya, along with Singapore merging with the Federation with somewhat more autonomy. Thus, Malaysia was established on 31 August 1963 with the purpose to reduce or eliminate the threat of communism and secure independence from colonial rule. Singapore, it had been feared, would, if permitted to achieve separate independence, become a ‘Cuba’ at the bottom of the Peninsula (Deputy Prime Minister Tun Abdul Razak in Washington, Malayan Times, 27 April 1963). Independence, it seemed, would mean industrialisation would be a necessary evil.

The seeds of what was to become a major industry in Malaysia were sown by then Malaysian Minister of Commerce and Industry, Dr Lim Swee Aun, in 1963. On his way to the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade Conference (GATT) in Geneva that year, Dr Lim confirmed that his ministry had received many inquiries from foreign and local firms regarding the possibility of setting up vehicle manufacturing factories in the Federation. The bigger plan, he subsequently announced, was to establish a motor vehicle industry in Malaysia by stages – from basic assembly with some local content, to chassis build, and finally to a fully local-made car.

A Chronological Perspective 1963–1968

The Government blueprint for a local automotive market, established ahead of Malaysia’s independence in 1963, was to utilise local manufacture as much as possible – tires made by Dunlop, cushions from Dunlopillo, electric cables, batteries and paints that were already being manufactured in Malaysia.

In June 1963, the Malay Mail ran an article titled “Foreign Firms Plan to Make Cars in Malaya”. Survey teams from a number of foreign automobile manufacturers were reported to have reconnoitered the landscape for sites and were now looking for incentives such as pioneer status and tariff protection before taking the next step. This was not just press hype. Ford had just purchased 100 acres of land on top of their existing assembly plant in Singapore, and other firms had had discussions with the relevant ministries in Malaysia. Dr Lim Swee Aun had already accepted proposals from several foreign car manufacturers and while uncommitted on government findings, he did give the assurance that if the proposals were reasonable, their requests for tariff protection and pioneer status would be considered.

That year, both Malaysia and Singapore were looking to encourage the establishment of automobile assembly plans handling completely knocked down (CKD) operations, plus progressive manufacture. Cycle & Carriage Co. Ltd. (C&C), which held the franchise for Mercedes-Benz, Chrysler and Jaguar, was keen to explore their options further, initially with car assembly in Singapore and heavy vehicle assembly in the Peninsula on the basis that a “common market” existed between the two. C&C eventually did begin assembly of both Mercedes-Benz and Mitsubishi cars five years later in 1968, with Mercedes-Benz at Petaling Jaya, Selangor and Mitsubishi in Tampoi, Johore under a reorganised Group structure to incorporate the separation between Malaysia and Singapore in 1965.

At the opening of the Made-in-Malaysia trade fair in Kuala Lumpur on 29 October 1963, Dr Lim Swee Aun announced the cooperation between the Central Government and the State Government of Singapore on working out a car industry program. The exhibition featured two Ford cars – the Consul and the Cortina, both provided and assembled by Ford Motor Company (Ford) in Singapore. Dr Lim acknowledged that local content of the car was, however, modest with only tires, seat cushions, electric cables, batteries, paints and windshield weatherstrips being locally produced by Dunlop, Associated Batteries, Malayan Cable, Kinta Rubber Works, P.A.R. and Dunlopillo. Ford, which had the only car, truck and tractor assembly plant in the Federation for more than 30 years (Wearne Brothers actually had a very modest assembly operation for Ford cars in Singapore in 1916), had ensured that all local components had met with its international specifications. Ford Malaysia’s Managing Director (1947–1951, 1957–1964, 1985), Gordon W. Withell, had endorsed the use of local products as long as they met with internal quality specifications, delivery requirements and cost factors.

Ford already had an assembly plant in Bukit Timah, Singapore that had produced over 80,000 vehicles since it started production in November 1926. By 1965, Ford was assembling 16 models of cars, from the Anglia to the Cortina, although production capacity was a mere 13 units a day (with overtime they were able to push the figure up to 18 units a day).

The Central Government did realise that a Made-in-Malaysia car would take a long time to evolve. Their farsighted approach budgeted for up to 20 years before fruition of a locally manufactured car (which was exactly how long it did take), however the initial plan was to grant to a number of manufacturers/ ventures licences to assemble vehicles similar to what Ford had been doing at their Singapore facility.

The Federation had seen 22,000 vehicles of all sorts imported into the country in 1961. China, for example, imported an average of 1,000 passenger cars per year from 1954 to 1965, mostly from Poland! For a viable car assembly plant in the Federation, annual output was estimated to have to top 3,000 units. Word amongst industry participants circulated that there were several very interested parties, from Australia, Europe to Japan, prepared to invest in building assembly plants in Malaysia. The industry waited with bated breath to see who would be the first mover.

The Straits Times headlines on Sunday, 10 November 1963 read: “The Motor Millions: Five Assembly Plant to Go Up in Big Car Deal.”

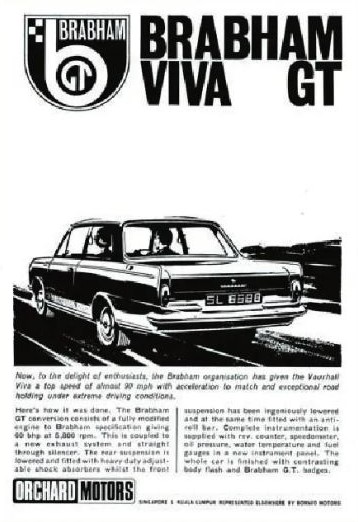

Amidst rife speculation and concern about the extent of import duties and tariff protection to be imposed on vehicle imports, the “Motor Millions” newspaper report revealed the first five motor agencies that were keen to establish assembly plants in Malaysia. The five firms were: Malayan Motors of the Wearne Brothers Group together with Borneo Motors and BMC-Far East (who would produce Austin, Morris and other BMC vehicles); Cycle & Carriage (who would produce Mercedes-Benz and Chrysler vehicles in two plants); Champion Motors (who would assemble VW and Rover, including Land Rover); and Orchard Motors (who would assemble Vauxhall and Bedford vehicles and possibly other General Motors cars and commercial vehicles).

The Japanese too were most keen to establish a foothold in Malaysia and by the end of 1963, Kah Motors, a subsidiary of Tan Sri Loh Boon Siew’s Oriental Holdings Ltd., and Toyota Motor Co. (Toyota) of Japan had begun building an assembly plant for Toyota cars in Butterworth, Penang. In Oriental Holdings’ prospectus (22 February 1964) for the public subscription of 2.6 million ordinary shares of $1 each, it was stated that negotiations were in progress for the construction and operation of the plant as a Joint Venture between Kah Motors and Toyota. Kah Motors had been appointed sole agents for the sale of Toyota cars and commercial vehicles in Malaysia, including Singapore, for five years up to September 1968.

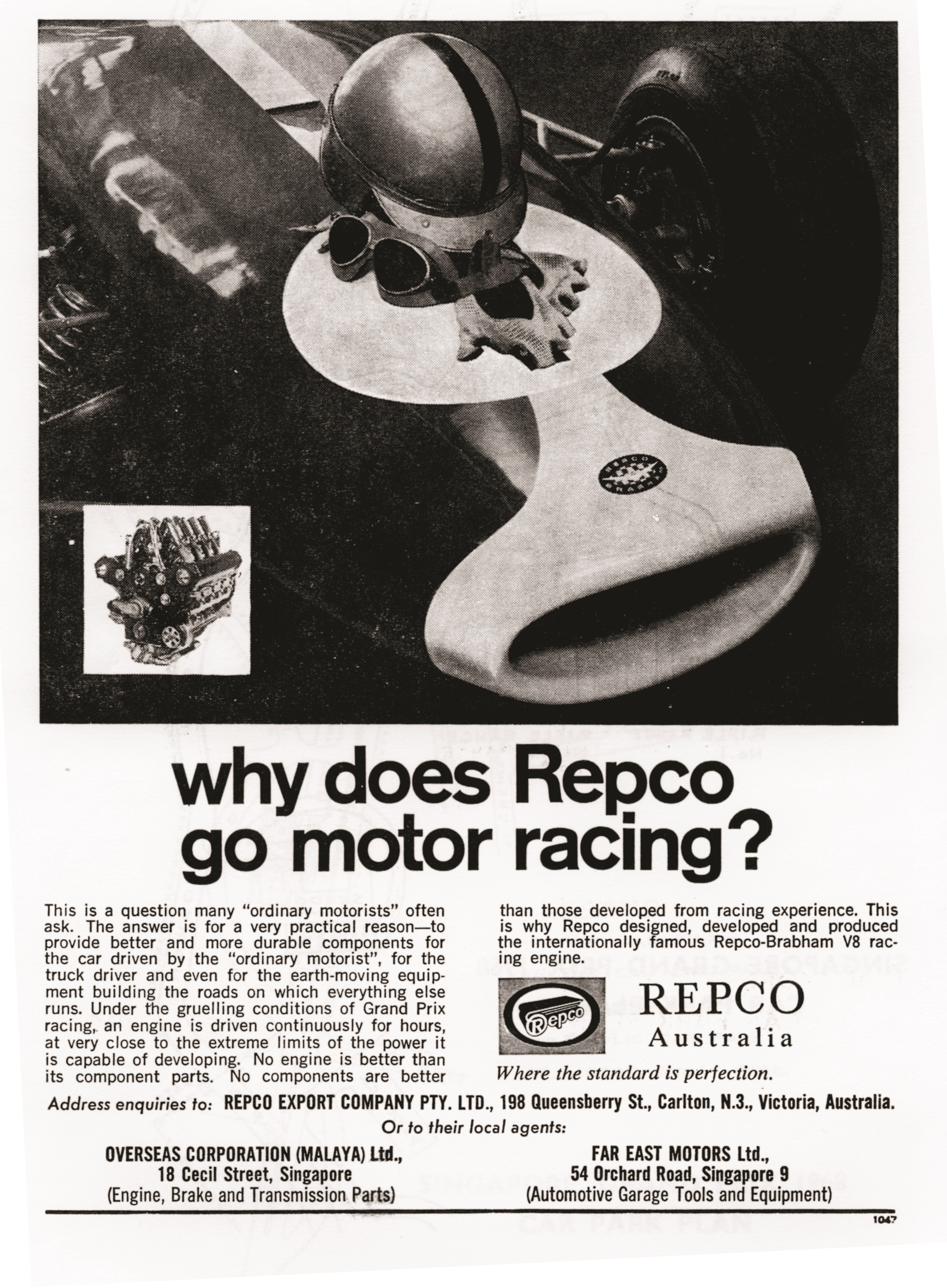

At the end of November 1963, representatives from Australia’s Repco Ltd *, the biggest automotive spare parts manufacturer in the Southern hemisphere, had spent a week in Singapore studying the possibility of setting up a spare parts plant. Repco was already supplying parts for Holden, Ford, BMC, Chrysler and General Motors vehicles.

The following year, 1964, was to be a very exciting one for car manufacturers and agencies prepared to assemble their cars in the Peninsula. The Central Government was confident that the first made-in-Malaysia (i.e. assembled) car would appear on the roads by the end of that year or in early 1965 (The Malay Mail, 24 January 1964). Several manufacturers had already invested in large tracks of land in Selangor, Perak and Penang. Toyota, as indicated earlier, was establishing their venture in Penang; Chrysler and VW were to set up theirs in a 700 acre site at Batu Tiga in Selangor; Orchard Motors, the Vauxhall and Bedford distributors, were keen on a plant in Kuala Lumpur; Asia Motors, agents for Peugeot, BMW and Borgward cars, were interested in a plant at the new Jurong Industrial part in Singapore; and Cycle & Carriage, agents of Mercedes-Benz, Auto Union, DKW, Plymouth, Valiant, Chrysler, Imperial, Simca, Jaguar, BSA, Trojan and Willys, were interested in setting up assembly plants at a couple of sites in Malaysia (The Straits Times, 9 February 1964). It seemed that all that was needed was the green light from the Central Government.

At the end of May 1964 a number of headlines flashed across the press: “Batu Tiga: 200 acres Already Booked”, “Two-government Speed Up of Car Industry”, “Motor Men Keen on Assembly Plants”.

It was now fairly clear that the Central Government and the State Government of Singapore had decided to speed up the development of the motor-vehicle industry. Applications for the setting up of such assembly plants would be opened for tender until 1 August 1964 (later extended to 1 September 1964).

Dr Lim Swee Aun reiterated the Central Government’s call for the setting up of assembly plants in Malaysia (Malayan Times, 28 May 1964). The rules were laid down that all completely-knocked- down (CKD) vehicle packs were allowed to be imported free of duty except, initially, tires, tubes and batteries. The government would give reasonable tariff protection by imposing duty up to a maximum of 30% Ad Valorem of full value and 15% Ad Valorem respectively on all completely-built-up (CBU) and semiknocked-down (SKD) passenger cars, and up to a maximum of 30% Ad Valorem and 20% Ad Valorem respectively on CBU and SKD commercial vehicles. All imported or locally assembled vehicles would have to pay the existing initial Ad Valorem registration fee that would be based on the Cost, Insurance and Freight (CIF) process of identical CBU models. To encourage local manufacturing, an assembly tax of up to 3% (rising in 2% increments per annum to 12% by 1974) of the value of the car would be imposed on assemblers who did not use at least 8% (rising to 20% by 1974) Malaysian content by February 1968.

It was also stipulated that no pioneer status would be granted in respect of motor vehicle assembly operations but the Government was prepared to grant pioneer status, and introduce the necessary tariff protection, for the local manufacture of parts and components. The Government was very much in favour of ensuring the local manufacture of the following: trimming materials, seat frames, leaf and coil springs, silencers and exhaust pipes, radiator and radiator cores, fan belts, shock absorbers, sealing materials, brake lining and related parts, safety glass, sparking plugs, canvas hoods and bumper bars. The basic consideration for the adoption of this policy was primarily to encourage the use of parts and components made in Malaysia, to keep costs and prices of vehicles assembled in Malaysia at the lowest possible level, and continue a free and competitive market in motor vehicles. The benefits were substantial – the creation of an industry involved in the design and manufacture of spare parts for the automotive sector.

In June 1964, Nissan, another Japanese manufacturer, disclosed that it was studying a Malaysian offer to exempt duties on automobile parts imported for assembly in Malaysia. The company was also considering plans to establish an assembly plant in Malaysia. Tan Chong Motors had become an appointed franchise holder of Nissan (Datsun) vehicles in Malaysia in 1957 but their first assembly plant would not commence production until 1976. In the meantime, Capital Motors’ assembly plant in Tampoi, Johore was contracted to assemble the Datsun SSS. Honda too, were keen to establish an assembly plant in Malaysia and did so in 1969 with Kah Motors, after Kah had lost its Toyota franchise to Borneo Motors in 1969.

It appeared that everyone had wanted to get into the act. Australian manufacturing concern, Lightburn & Co. of Adelaide, was an exporter of hydraulic car jacks, washing machines and other white goods, cement mixers and fiberglass boats. The Adelaide company had perceived a need for a minicar and had come up with a hideous assemblage that they thought could pass off as a car. They called it the Zeta and it was priced in the Australian market at less than A$600 ($4,080 in local Straits dollars). Lightburn structured a package for the Government that included a complete car manufacturing plant in Malaysia that would cost about A$250,000 and include a 30,000 sq ft pre-fabricated steel building, tooling jigs and moulds for the fiberglass Zeta bodies. What became of the Zeta is beyond the scope of this paper. Suffice to say, it would have been interesting to know if there were any inquiries from the region, or even a single sale of the vehicle in the Peninsula.

Hitherto the Malaysian motor vehicle market had been the domain of Britishbuilt machinery. British domination in the car market, however, started to erode with the entry of the Japanese manufacturers. The Sunday Times ran an article titled “Japanese Second Invasion” on 13 September 1964. For British businesses in the Far East, it would be a fight to survive the onslaught of the tin tops from Japan. By May 1964, the writing was on the wall. The Nissan (Datsun) equivalent of the Austin 1100 had outsold its British counterpart by a factor of 161 to 124. Nissan had been producing the Austin A40 under license from 1952, which had enabled the Japanese to acquire Austin’s valuable knowhow (Nissan’s first foreign assembly venture plant would however be a plant in Mexico in 1966). Apart from Nissan, Toyota was also emerging with competitive models. Despite punitive import duties on non-Commonwealth makes, the Japanese were able to increase their local market share to over 25%.

The effect of all this competition, together with the stark reality of the slippery slope the British car industry was descending into, was that local importers were forced to access their situation and consolidate their positions or lose market share. Or, as one local car executive had aptly put it, “If my principals don’t agree to local assembly, I am sunk. Kaput. Out of business”

With the exception of Cycle & Carriage’s overriding principal, Daimler Benz’s insistence that C&C streamline their list of agencies down to just two (Mercedes and Mitsubishi), the others (such as Borneo Motors) were compelled to cast out a wider net of agencies. The Central Government was relishing every minute of this as it led to the promotion of competition.

In February 1965, Tan Siew Sin, the Malaysian Finance Minister, voiced a point of concern of the Central Government – the alarming rate of industrial development in Singapore. The uneasiness was that industrialists were now bypassing the Central Government and dealing directly with the State Government of Singapore. A few days after Tan’s speech, Singapore’s Finance Minister, Dr Goh Keng Swee, warned that sniping in public and denigration of both the governments’ efforts would not do either any good. Dr Goh’s views on the matter were well articulated and carried by the local press. Resolution came not long after by way of separation and the establishment of the independence of Singapore, and what would amount to separate policies on either side of the causeway for a market that had thus far been considered a single market.

In Malaysia, the Malay Mail of 27 January 1965 had intimated that at least five international motor manufacturers would have their applications to build assembly plants in Malaysia approved by the government. The number of applications had totalled a massive 17!

The Japanese had studied the export market quite thoroughly and were looking to arrange the ‘orderly sales’ of their products in overseas markets. The Japanese trade ministry highlighted the need to minimise competition among themselves by organising Japanese motor manufacturers into groups instead of six firms heading their separate ways overseas. Without being able to replicate the keiretsu** structure at home, the Japanese motor manufacturers were thus forced to innovate fairly early and establish the practice of using common suppliers while operating overseas, a practice they eventually brought home to Japan (Humphery et al, 2000).

During the first week of March 1965, the Malay Mail carried an interesting editorial that reflected a great deal of maturity and foresight. Titled “Towards Our Own Car” the last paragraph read, “Eventually this process of assembly merging into production will lead to a totally made-in-Malaysia vehicle; a vehicle… which should be comparable in price and quality with its overseas counterparts.

This is a goal so far removed from this week’s foundation stone ceremonies [referring to the laying of the foundation stones for two motor vehicle assembly plants in Singapore and in Petaling Jaya, Selangor], but not too far for contemplation.”

In August 1966, the Malaysian Government eventually scrapped Commonwealth preferential rates on a wide range of articles, including cars. The underlying objective was to boost government revenues by $27m to finance the First Malaysian Plan after independence. The result was a five to 25% rise in the cost price of imports from the Commonwealth. British motor vehicles claimed around 50% of the Malaysian market and British cars such as Jaguars and Rovers would now cost at least $1,500 more per car. Wearne Brothers found that selling prices would have to increase by $600 (Straits dollars) for their smallest model to $1,500 for their bigger ones. Sales started to slacken almost immediately for companies importing from the Commonwealth. Others were untouched by the withdrawal of preferential rates and Chua Boon Unn, Cycle & Carriage’s Managing Director, was keen to highlight that the Mercedes-Benz was non-Commonwealth and therefore unaffected by the Malaysian Government’s move and any price increases.

The Government applied a measure of encouragement and coercion when it arrived at determining policy for the automotive sector. It felt that a tariff on assembled cars with zero local content as well as a quota on imported cars was reasonable. Within a year, this policy was adjusted to pace the development of the motor assembly industry and a 30% duty on all imported cars was shelved (The Straits Times, 11 July 1967) in favour of quota restrictions (set at 110% of 1964 – 1965 imports). Announcement of the 30% punitive tax had just been announced earlier in February that year that the Government had intended to implement within 18 months.

After much deliberation and numerous policy changes, the six companies finally granted approval in 1966 to assemble vehicles in Malaysia was announced. These were Asia Automobile Industries (making Peugeot and Mazda), Associated Motor Industries (making BMC, Ford, Holden, Renault and Rootes), Champion Motors (making VW, Mercedes, Toyota, Vauxhall and Chevrolet), Swedish Motor Assemblies (making the Volvo 122 and 144 models), Kilang Pembena Kereta2 (in association with Cycle & Carriage to make Mitsubishi Colts) and Capital Motor Assembly Corp. (making Opel and Nissan/Datsun).

Conclusion

From 1966, the automobile industry in Southeast Asia evolved from one of British domination to one of Japanese domination. A rapidly growing population and the need for Malaysia to develop different industries also suited the establishment of a local automobile parts and assembly industry. The larger global automobile companies had wanted to capitalise on such growing economies and were prepared to invest heavily in such plants. The early 60’s were therefore critical years in Malaysia as policies were formulated and waters tested for such industries. By the end of the decade, manufacturing and assembly plants were up and running and policies sufficiently polished to suit the turbulent economic climate. The period also saw the industry evolve and consolidate with the emergence of several bigger companies with local management and shareholding. Those that were able to adapt and develop new strategies to suit the formative years of government policy changes (Cycle & Carriage, Borneo Motors, Tan Chong Motors for example) were eventually to become major players in the following decades.

It would be exactly 20 years later that Perusahaan Otomobile Nasional Berhad (PROTON) was incorporated (7 May 1983), and Malaysia’s first locally built car, the Proton Saga, was launched on 9 July 1985.

Repco Limited – archives at the University of Melbourne (https://www.repco.com.au/about-us/. )

A keiretsu is a set of companies with interlocking business relationships and shareholdings. Taken from the Japanese term (系列) for “system” or “series.”

Capital Motors, the last and smallest of the initial six assembly plants, was established in 1967 by the following officeholders:-

Tun Haji Suliaman bin N. Shah: then Chairman UMNO

Leslie Eu: Managing Director

Stanley Leong: Singapore based Architect

Liew Kai Choon: KL businessman

Lim Phee Hung: Opel Penang Dealer Principal (Heng Guan) The Opel Ipoh Dealer Principal

Singapore Motors were behind the formation of Capital Motors and had the Pontiac, Opel and Suzuki motorcycle agencies. The company’s original owner was Chia Yee Soh, founder of United Motor Works, then Singapore’s largest spare parts dealer. Chai passed the company on to his son-in-law, Robert Eu, who in turn passed it on to his son, Leslie Eu. Leslie Eu was the principal owner of both Singapore Motors and Capital Motors during the 1960s. Stanley Leong, one of the other office holders of Capital Motors, had no financial involvement in Singapore Motors and was the architect for the Capital Motors plant in Johore with Chew Cheuk Loon acting as contractor. Stanley Leong and Leslie Eu were brothers-in-law. Rodney Seow, cousin to Leslie Eu, designed and installed the plant equipment and ran the Johore operations.

Assembly in Tampoi commenced with the Opel Kadett & Rekord in 1968 with 120 workers and the first vehicles rolling out in July that year. The Olympia, Manta, Izuzu Pickup & the Harimau (Basic Transport Vehicle) was subsequently introduced, together with contract assembly of the Datsun SSS and Honda Life. Production capacity, according to plant manager Rodney Seow, would be 3,840 vehicles a year.

The plant was then sold to General Motors (GM) in 1971 and the Holden range was transferred from the Associated Motor Industries (AMI - making BMC, Ford, Holden, Renault and Rootes) assembly plant in Selangor.

GM sold the plant to Oriental Holdings (Loh Boon Siew – Honda) in 1980 as the Malaysian government required Malaysians to have majority share holdings in the Assembly plant.

FURTHER READING

Eric Jennings, Wheels of Progress – 75 Years of Cycle & Carriage (Singapore: Meridian Communications (SEA), 1975). (Call no. RSING 338.7629222 JEN)

Henry Longhurst, The Borneo Story (London: Newman Neame Ltd., 1956). (Call no. RCLOS 959 LON)

Ilsa Sharp, Wheels of Change: The Borneo Motors Story ([Singapore]: Borneo Motors, 1993). (Call no. RSING 338.76292095957 SHA)

The Making of the National Car: Not Just a Dream (Kuala Lumpur: TASSMAG Publishing Sdn Bhd., 1994). (Call no. RSEA 629.22209595 THA)