Singapore Art, Nanyang Style

The Nanyang style of painting was practised by migrant Chinese painters in Singapore in the 1950s. It combines elements from the Western Schools of Paris with Chinese painting traditions, styles and techniques.

“Why, it is asked, do Chinese artists paint in oils instead of their own fluid and sensitive medium?… The answer is that no art that is alive can stand still; it must be a direct expression of the times. As Asian civilisations have been reborn in the last half century, so must Asian artists reflect, and inspire, this rebirth…” Art historian Michael Sullivan, 1963

The Nanyang style of painting was practised by migrant Chinese painters in Singapore in the 1950s; yet its parameters as a term were only spelled out by art historian T. K. Sabapathy much later in 1979 (Koay, unknown). The Nanyang style refers to the pioneer Chinese artists’ work which was rooted in both the Western schools of Paris (post-Impressionism and Cubism for example) as well as Chinese painting traditions; styles and techniques of both were distinctively integrated in depictions of local or Southeast Asian subject matter (Singapore Art Museum, 2002).

More notably, the Nanyang art style is the result of these artists having departed from their roots – but not entirely – to try to produce something uniquely regional. They aimed to represent pictorially the Nan Yang culture and way of life – Nan Yang meaning South Seas in Mandarin. As art historian Michael Sullivan pointed out above, these painters could be striving to produce an “expression of the times”.

But what led the artists to strive to create this regional style? What were “the times” as such? Apart from highlighting the major artists of the movement and their works, this essay will also attempt to trace the proponents of the Nanyang style.

Art World: Communities and Their Art Activities

The art scene in Singapore was a fledgling one in the late 1800s to early 1900s. The earliest works were oil paintings and lithographs made/commissioned by British settlers. The British however, concentrated on building infrastructure like housing, roads and hospitals in order to maintain a flourishing economy; they did not set up a specific art academy. Sir Raffles did have the intention to begin the teaching of art, but it was not executed until almost a century after his death, when the first English art teacher, Richard Walker, arrived in 1923 (Singapore Art Museum, 2002). It seemed, though, that Mr Walker was expected merely to fulfil the colonial school system requirements by teaching watercolour in art classes – art being one of the Cambridge examination subjects – and this frustrated him to no end (Purushotam, 2002; Kwok. 1996). The local art scene was therefore denied its development.

Singapore by 1840 had a huge influx of Chinese migrants. The overwhelming Chinese numbers were due to push and pull factors. There were the Opium Wars in the 1840s, which ended after the signing of the Nanking treaty that ceded Hong Kong and other trading ports in South China to the British Empire. This disrupted the economy there and spelled hard times for many Chinese of the lower classes – the result was the bloody Taiping Rebellion, of 1851–64. Many Chinese fled the country, attracted by the Western expansion of the “Far East” after the Industrial Revolution. There were many growing Southeast Asian markets which meant an increased demand for labour, for example in tin mines, and rubber, palm oil, and pineapple plantations (Wang, 1991).

The Chinese community held their own art activities. The first art society, the Amateur Drawing Association, was set up in 1909 (Kwok, 1996). Its members painted mostly Western oils or sketches. They were Straits Chinese, second-generation Chinese born in the Straits Settlements, the offspring resulting from intermarriage among the races. Known as Peranakans, they upheld not only Chinese but Malay and British traditions, and they often spoke Malay or English (Kwok, 1996).

On the other end of the spectrum was the United Artists Malaysia group based in Kuala Lumpur. Started in 1929, its artists concentrating primarily on Chinese ink painting and calligraphy (Kwok, 1996). Apart from the creation of art societies, the late 1920s to 1940s saw many travelling exhibitions being held in Singapore by China-based artists like Xu Beihong, Gao Jianfu and Liu Haisu (Kwok, 1996).

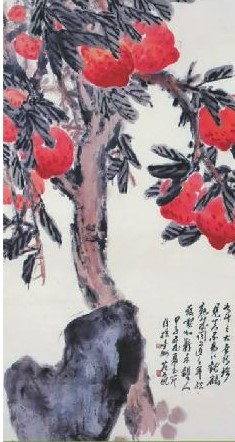

At this time, the trend for Chinese painting was called the “Shanghai School”. It followed the legacy of 19th century painters such as Ren Bonian and Wu Changshi, who painted with xieyihua – or the style of “writing ideas” – where the aim was to capture the essential meaning, or what one thought was the meaning, of a subject onto paper, rather than the reality of it. The style was much freer, bolder, and the artists liked to work with suggestion and omission hence the sparse, broad strokes and important consideration of empty versus filled space (Kwok, 1990). Chinese painters of this style who were based in Singapore include Fan Chang Tien and See Hiang To. Figure 1 shows Mr Fan’s rendition of a peach tree in this style, which he continued to paint in, late into his career. This xieyihua became the main form of Chinese ink painting practised in Singapore in the 20th century (Kwok, 1996), and can be traced as an important element of some of the Nanyang style artists’ works.

The Great Depression of 1930–34 hit Singapore however, and called a halt to most art activities. However after that, life resumed with local artists receiving even more exposure to art trends of Europe and China. There were European painters like Eleanor Watkins and impressionist Adrien-Jean Le Mayeur who lived or exhibited in Singapore (Kwok, 1996). There was also the creation of the Society of Chinese Artists in 1935. Its members, mostly the alumni of Shanghai art schools and other prominent academies, were inspired by Western art and its trends (Purushotam, 2002). This was a result of China’s May Fourth movement (1919) – an intellectual and political call for reform that aimed to revitalise the country through cultural change. The society also brought in exhibitions by painters from China and Hong Kong (Chia, 1982).

Then in 1938, there was the creation of Singapore’s first art academy, the Nanyang Academy of Fine Arts (NAFA). This was not the work of the British, however, but that of Chinese migrant artist and teacher Lim Hak Tai who managed to get funding from rich businessman Tan See Siang, to start this school (Koay, unknown). The school, entirely backed by the Chinese community, was modelled after the Shanghai art academies in its curriculum of both Western and Chinese art traditions, and would prove to be crucial to the fostering of the Nanyang style – for the principal artists of this movement were also teachers there (Chia, 1982; Purushotam, 2002).

The term Nanyang: Imparting Ideals of Regionalism

How did the idea of a Nanyang style come about? The term Nanyang itself was originally coined by newspaper critics of the late 1920s to early 1930s, to denote contemporary Chinese stories that were written based on local Singaporean subjects (Kwok, 1996). Gradually the term was taken further to impart the idea of a Nanyang identity and regional culture for the overseas Chinese in Southeast Asia. The dichotomy of Chinese nationalism and Southeast Asian regionalism grew: the emphasis by proponents of Nanyang ideals was on one’s locale being one’s new home, and the need to forge a new identity in new lands.

However, exploring that ideal was suspended when World War II broke out and the Japanese occupied Singapore from 1942–5. However after the war, Nanyang regionalism strengthened even more amid growing anti-colonial sentiments. The British were drafting a Malayan confederation, but Singapore was left out to remain as a British colony despite its people warming toward the idea of independence (Xia, 2000). NAFA, which resumed classes then, began to draw artistic inspiration from its Southeast Asian surroundings, instead of its prior pro-China stance. The mid-40s to early 50s saw the growth of many painters alongside the growing patronage of exhibitors like the British Council (Kwok, 1996). With the renewed talk of a Nanyang identity, there also began the quest to find the quintessential Nanyang visual expression to go along with it. What was the Nanyang South Seas culture, and how could one pictorially express it?

Nanyang Style Painters: The Pioneers

Several artists credited with forming and espousing the Nanyang style emerged during the late 1940s/50s. Their primary medium was either Chinese ink/colour, or oil on canvas. Four stand out from these, for their growth as artists was spurred tremendously by their trip to Bali in 1952 (Kwok, 1994). These painters are Cheong Soo Pieng, Chen Chong Swee, Chen Wen Hsi and Liu Kang. The artists were struck by the exoticism of Bali, and having gained inspiration from the bright colours, sights and sounds of Bali, they tried to incorporate these in their formations of the Nanyang style. All four were graduates of Shanghai’s XinHua Academy of Fine Arts, all taught at NAFA at some point, and all had exposure to the varied French schools of art – whether through self-exploration by living in European cities for periods at a time, or via art journals and communication with European artists based in Southeast Asia (Kwok. 1994; Chia, 1982). Each worked to articulate a Southeast Asian viewpoint through the integration of Chinese and Western elements in their works, yet we will see how each had their own individual style.

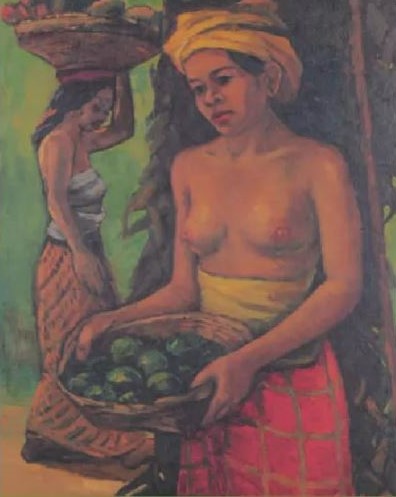

Among the four that went to Bali, Chen Chong Swee (1910–1985) can be considered the most realist of them. Trained in traditional Chinese brush painting, he was also one of the founding members of the Society of Chinese Artists. A firm advocate of the May Fourth Movement, he called for the marriage of the Western principle of creativity with the Chinese virtues of imitating the masters. He also believed in painting “in his time”, drawing inspiration for meaningful pieces from his present surroundings (Koay, 1993). He was thus one of the first to paint local themes using a Chinese landscape painting format. But after Bali, he dabbled in oils as well. Figure 2 is one of the works resulting from that trip. He wrote: “Bali is indeed a women’s empire; the robust beauty of Balinese women and the pastoral scenery form an excellent painting (Kwok, 1993).”

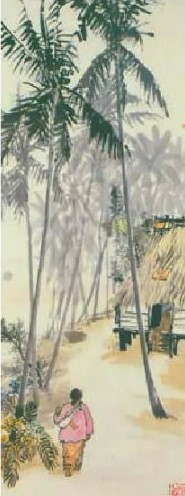

Despite this foray into oils, Chen Chong Swee’s forte still lies in his “Southeast Asian” landscapes and vignettes in the traditional Chinese scroll format. Figure 3 shows one such example, done in Chinese ink but with a Western fixed perspective angling into the distant coconut trees. All of Mr Chen’s realist works never strayed far into the murky waters of subjective expressionism because he believed that a painting’s content must be understood for it to mean something and elicit a response from one’s audience (Koay, 1993).

Besides painting, he was a great writer and contributor to the press on art theories, espousing his conviction to realism in articles and the colophons in his paintings (Kwok, 1994).

The next artist Chen Wen Hsi (1908–1991), however, did not care for active discourse on the Nanyang style, but rather was a staunch individualist. If Chen Chong Swee was the realist, he was the abstract cubist. In the early years and before retirement, he too painted primarily with Chinese ink and of local subjects in the style of xieyihua.

Later on though, he placed this Chinese aesthetic together with western pictorial composition, going so far in his later years to produce abstract iconic oils such as Figure 4 (next page), which depicts herons in an angular, Cubist manner – a work of Chinese ink and colour. Art patron and journalist Frank Sullivan has noted, “Although interested in angles, (Chen Wen Hsi) is not a cubist; although obsessed by shape, he is no abstractionist; he strays from reality, but not too far (Chen, 1956).” So, Chen Wen Hsi seems to have always remained true to his unique art philosophy and style.

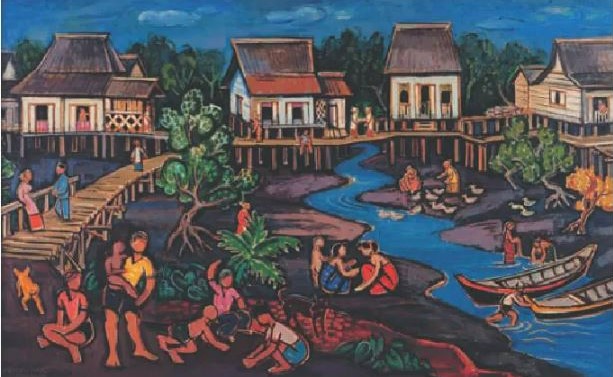

The next Nanyang artist is Liu Kang (1910–2004), and his work differs in that he is post-Impressionist and Fauvist influenced, but his choice of subjects is again, local. While he too was a XinHua student born in China, he graduated slightly earlier than Chen Chong Swee and Chen Wen Hsi, in the late 1920s, and went straight to Paris after that. He spent six years painting there, exposed to the works of Degas, Gauguin, and Matisse etc (Kwok, 1996). He then returned to Shanghai to teach Western art, before coming to Singapore in 1942 (Koay, unknown). Figure 5 which depicts a river kampong scene, is an example of his typical work being Fauvist in nature with the flat, broad sheets of colour, but he also used the arrangement of shapes rather than shading to achieve depth, and his arrangement of subject allowed the eye to travel instead of fixing on one point into the distance – both techniques are more in tune with the Chinese landscape format than Western art. Liu Kang’s primary medium has always been oils on canvas. His works are always simple and realistic but without being naturalistic.

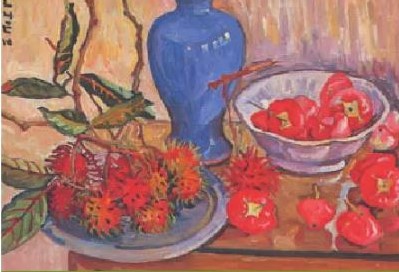

Like Liu Kang, the next China-born artist Georgette Chen (1907–1993) was also post-Impressionist inspired and primarily worked with oil and pastels. She was not part of the foursome who went to Bali, but she too dabbled with the techniques of Chinese brushwork using oils. Georgette Chen was born to wealth and privilege, having been educated in France, New York and Shanghai. She had even exhibited in the Salon d’Automne in Paris in the 1930s (Chia, 1995). Her early works were Cezanne-influenced with strong textures and a predilection for topdown views. When she moved to Singapore in 1954, Georgette Chen taught at NAFA (Kwok, 1996) and painted more local subjects, whether landscapes, still-lifes or portraits, such as Figure 6’s Still Life with Blue Vase, which has the rough brushstrokes of post-Impressionism but a faint touch of Chinese painting style in the thin outlines. In this insistence on an Asian context much like Liu Kang’s own philosophy (Chia, 1997), Georgette Chen often chose familiar, commonplace objects because of their cultural significance, such as mooncakes – icons of the Chinese mid-Autumn Festival or tropical fruit like rambutans. Georgette Chen herself once said, in 1979: “…it seems that I have passed by many art trends such as Dadaism, Cubism and more recently kinetic, op, pop…I have just continued to be attracted by the people around me, their lives, objects and the glorious landscape of Mother Nature.” (Purushotam, 2002) Her later years in Singapore mark Georgette Chen’s maturity as an artist, in her emphasis on pictorial composition, and in her search for new permutations of shapes, colours and textures. If you compare Figure 6 with Figure 7, you can see the sophistry gained in the latter and the more expressionist flavour in the former.

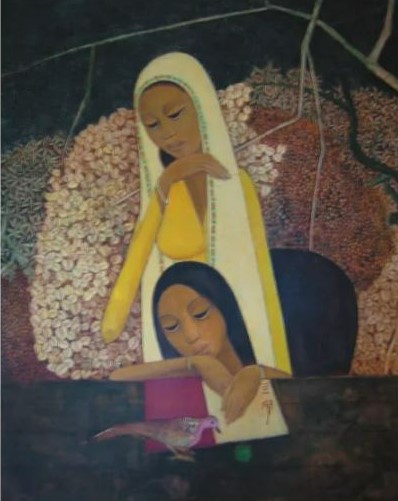

Last but not least of the Nanyang pioneer artists is Cheong Soo Pieng (1917–1983). A XinHua graduate as well, he came to Singapore in 1946 and taught at NAFA until 1961 (Chia, 1982). These years saw him try to capture his new environment in all its colours and charms. Always experimenting with pictorial compositions, he was eager to try all sorts of mediums as well. Throughout his whole art career, he had dabbled with oil in impasto, Chinese ink on rice paper, oil with new effects, abstraction, mixed media sculptures, painting on tiles and porcelain, and Chinese painting on cotton (Kwok, 1996). Cheong Soo Pieng’s visit to Bali saw him inspired to experiment with the depiction of the human form, resulting in the beginnings of an iconic stylised and abstract figure with large eyes and long limbs. He went on to dabble in abstract expressionist styles, but in his later years he drew renewed inspiration from Bali and further honed his iconic depiction of the Malay woman with elongated limbs, which he is now most famous for (See Figure 8). This has led to critics lauding Cheong Soo Pieng for his Balinese series of oils as being “modern and international in technique, Chinese in feeling, and Malayan in subject” (Cheng, 1956). The paintings all have mellow, earthy colours reminiscent of the Balinese palette, but at times are highlighted with bright patches of colour.

Conclusion

The history of Singapore with its blend of Western and Eastern influences yields many clues to the components of the Nanyang style. Chinese art trends (namely the Shanghai School’s revitalization of xieyihua) were central to the Nanyang style and the politics of the post-war era had spurred the quest for depicting Nanyang regionalism in the first place. On the other hand, the May Fourth movement’s Western ideals and British colonialism brought with it more exposure to art trends of the West, namely the schools of Paris. It is interesting to note that if the British had been more eager to impart their artistic ideals by setting up an academy like the French in Indochina or the Dutch in Indonesia, Singapore’s Nanyang style might have been a very different one – the coalescing of techniques might have resulted in a different outcome altogether.

Lastly, the budding infrastructure of art societies and institutions allowed the proliferation of exhibitions by foreign artists both Chinese and European, which thus ensured wide exposure for Singapore artists to all sorts of manner of painting. Furthermore, without NAFA and the artists as teachers, the Nanyang style would not have been thoroughly fostered for later generations of artists in Singapore.

But has that fostering been effective? Art historian T. K. Sabapathy had once criticised that the younger generation of artists such as Yeh Zhi Wei and Choo Keng Kwang who continued the Nanyang style in the 1970s (Kwok, 1996) do not have the spontaneity and spirit of innovation as their forefathers, the results being “tiresome clichés”(Koay, unknown). But perhaps this is the artist’s natural result in again trying to reflect and express “the times” – in this case, society’s nostalgia of the old – for running concurrently then was the issue of how to tackle rising modernism and Western culture influences on Singapore (Xia, 2000). It would seem that harking back to the pioneer artists’ Nanyang style, turning their techniques into easy rules of painting, was itself a statement on this issue, however stiff and formal the actual result seemed.

Nevertheless, the proponents of the Nanyang style continue to resonate today. What is most noteworthy is the fact that this art style reflects the universal culture of migrants, who in this case adapted to and accepted a new mix of Western, Chinese and indigenous beliefs/practices. The lessons learnt from this art movement are therefore no less significant in this global age, with infinite possibilities nowadays for the cross-fertilisation of cultures in every corner of the world.

Reference Librarian

Lee Kong Chian Reference Library

REFERENCES

Chen Zongrui, Chen Chong Swee: His Thoughts (Singapore: Singapore Art Museum, 1993). (Call no. RSING 759.95957 CHE)

Chia Wai Hon, Singapore Artists (Singapore: Singapore Cultural Foundation, 1982). (Call no. RSING 759.95957 SIN)

Jane Chia, “Trouble at Hand,” Art and Asia Pacific 2, no. 2 (April 1995).

Jane Chia, Georgette Chen (Singapore: Singapore Art Museum, 1997). (Call no. RSING q759.95957 CHI)

Kwo Da-Wei, Chinese Brushwork in Calligraphy and Painting: Its History, Aesthetics, and Techniques (New York: Dover Publications, 1990). (Call no. 745.619951 KWO)

Kwok Kian Chow, Channels & Confluences: A History of Singapore Art (Singapore: Singapore Art Museum, 1996). (Call no. RSING 709.5957 KWO)

Kwok Kian Chow, Images of the South Seas: Bali as a Visual Source in Singapore Art. In From Ritual To Romance: Paintings Inspired by Bali (Singapore: Singapore Art Museum, 1994)

S. Xia, “Nanyang Spirit: Chinese Migration and the Development of Southeast Asian Art,” in Visions & Enchantment: Southeast Asian Paintings (Singapore: Singapore Art Museum, 2000). (Call no. RSING q759.959 VIS)

Singapore Art Museum, Singapore Modern: Art in the 1970s (Singapore: Singapore Art Museum, 1970). (Call no. RART 709.95957 SIN)

Singapore Art Society, Chen Wen Hsi: Exhibition of Paintings (Singapore: Singapore Art Society, 1956). (Call no. RCLOS 759.9595 SIN)

“Singapore History Since Its Early Beginnings,” Asia Web Direct, 2005.

“Singapore Infomap: Nation’s History,” Ministry of Information, Communications and the Arts, accessed 16 November 2005, http://www.sg/.

Susie Koay, Singapore Artists – Some Observations on the First Generation (Singapore: Singapore Art Museum, n.d.)

Susie Koay, “Chen Chong Swee: His Art,” 1993.

Venka Purushothaman, Narratives: Notes on a Cultural Journey (Singapore: National Arts Council, 2002). (Call no. RSING 700.95957 NAR)

Wang Gungwu, Singapore Modern: Art in the 1970s (Singapore: Times Academic Press, 1991). (Call no. RSING 327.51059 WAN)

Zhong si bin 钟泗滨 [Cheong Soo Pieng] (Xin jia po 新加坡: Straits Commercial Art, 1956). (From PublicationSG)

FURTHER READINGS

Jane Chia, Georgette Chen (Singapore: Singapore Art Museum, 1997). (Call no. RSING q759.95957 CHI)

A detailed study on the life of Georgette Chen, the book also compiles a chronology of all her major exhibitions and the works featured in them.

Kwok Kian Chow, Channels & Confluences: A History of Singapore Art (Singapore: Singapore Art Museum, 1996). (Call no. RSING 709.5957 KWO)

A fully illustrated book which outlines the history of the visual arts in Singapore from about the twentieth century. The study highlights many historical and aesthetic themes and issues, which are vital to the understanding of the development of the visual arts in Singapore.

Liu Kang, Journeys: Liu Kang and his Art (Singapore: National Arts Council and Singapore Art Museum, 2000). (Call no. RSING q759.95957 LIU)

In commemoration of the diplomatic relations between the People’s Republic of China and Singapore, this traveling exhibition featured 50 key works from every notable period in Liu Kang’s career. Reflections on his paintings and art are expressed in both English and Chinese.

Marco C.F. Hsu, A Brief History of Malayan Art (Singapore: Millennium Books, 1999). (Call no, RSING 709.595 HSU)

Translated from Mandarin to English, this work discusses the various factors that have shaped the art scene in present-day Singapore and Malaysia. It traces the area’s art, personalities, events and organisations from the time of the early settlers. Topics covered include the spread of Islam, the transmission of Western cultures and the nurturing of painting.

Tan Meng Kiat, The Evolution of the Nanyang Art Style: A Study in the Search for an Artistic Identity in Singapore, 1930–1960 (Hong Kong: Department of Humanities, University of Science and Technology, 1997). (Call no. RSING q709.5957 TAN)

This thesis studies the reasons and events behind the evolution of the Nanyang Art Style in Singapore, from 1930–1960. It is divided into two parts: the first covers the history of the country and the other analyses the art style itself.