Tongkangs: Hybrid Ships in a Moment of Singapore’s Maritime History

The history of the tongkang industry in Singapore began with the arrival of Stamford Raffles in 1819. With the establishment of the island as a trading centre, merchants from around the region and beyond began flocking here. Tongkangs were the chief means of sea transport, carrying men and goods between South China and Nanyang.

The history of the tongkang industry in Singapore is part of the history of enterprise in Southeast Asia. The history of the industry began with Sir Stamford Raffles in 1819. As soon as Raffles laid down the commercial foundations of the island, merchants around the region and beyond arrived and began operating from this rapidly expanding centre of trade. The Singapore merchants acted as the agents of exporters in China, selling on their behalf, the produce, mainly foodstuffs, of the coastal provinces of South China – Fujian, Guangdong and Hainan Island. The main ports for this export trade were Amoy, Swatow (Shandou today), and Hoi How, the capital of Hainan.

During the 19th and early 20th centuries, there were relatively few steamships, so that the main part of the trade between China and Singapore was handled by Chinese junks, and later the tongkangs. These vessels were the chief means of sea transport, carrying men and goods between South China and the Nanyang (South Seas) countries.1 They also called at ports in Indo-China, Burma and Thailand. Excluding trade with Europe, which was carried by steamships and English lighters, the major portion of Eastern trade was carried by tongkangs.

Gradually, however, the shipping lanes, mostly European, gained control of this Eastern trade with faster and more efficient steamships. Faced with this competition, junks and tongkangs declined in importance but retained control of the coastal and interisland trade. Being smaller vessels, they were able to negotiate small rivers and anchor in shallow waters. In fact, the tongkang was built in such a manner that it could lie on river beds without tilting over when the tide was out.

In the early part of this period, the junks plying between China and Singapore were owned by traders in China. As merchants in Singapore prospered, they acquired their own vessels built in China. From the initial role of agents, these traders began to fulfill a new economic role by providing shipping services.

Towards the end of the 19th century, these merchants began building their own sailing vessels locally. This was made possible by the migration of Chinese ship-builders and master craftsmen to Malaya who came with the general flow of immigrants. It is difficult to set an exact date when the vessels were built locally and thus determine the beginning of the tongkang industry proper. Records at the Singapore Registry of Ships showed that from about 1880 onwards, an increasing number of vessels registered were locally-built sailing vessels. They were called “tongkangs” and were anchored along the Singapore River, especially between Read Bridge and Ord Bridge, forming part of the Boat Quay. The first Chinese boatyards were therefore situated here or further up the Singapore River.2 Most vessels registered in Singapore by the 1920s were built locally.

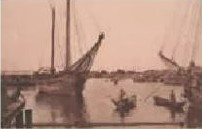

The building of bridges across Singapore River made it impossible, because of their low overhead, for tongkangs and other sailing vessels to sail up the river. Owners of tongkangs thus were compelled to shift their anchorage to the sea, off Beach Road and Crawford Street, which was the major anchorage for tongkangs until the building of the Merdeka Bridge in 1956. The Merdeka Bridge formed part of an important arterial road linking the East Coast areas to the city centre and the Singapore River area. Yet again, another bridge – Merdeka Bridge – then prevented tongkangs from sailing up the Rochor and Kallang Rivers to discharge their cargoes to warehouses along Crawford Street and Beach Road, and except for timber tongkangs, they shifted again to a sheltered anchorage built by the Singapore government along the Geylang River to Tanjong Rhu (known as Sandy Point in the earlier part of the 19th century), slightly further east.

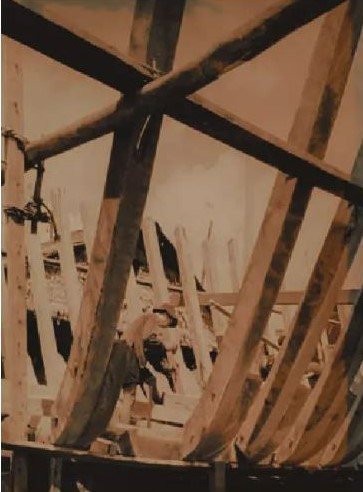

The Building of Tongkangs

The word “tongkang” is Malay, and is probably derived from belongkang (probably perahu belongkang), a term formerly used in Sumatra for a river cargo boat (Gibson-Hill, 1952:85–86).

Though the tongkang was Chinese-built, owned and manned, it was not of Chinese origin. Chinese boat-builders adopted the hull of the early English sailing lighter, building a hybrid vessel described as “a fairly large, heavy, barge-like cargo-carrying boat propelled by sail(s), sea-going or used in open harbours. In the immediate area around Singapore (Malaya), it signified a sailing lighter (or barge) with a hull of European origin, or a boat developed from such a stock” (Gibson-Hill, 1952:85–86).

There were generally two types of tongkangs in Singapore – the “Singapore Trader”, a general purpose cargo boat used mainly for carrying charcoal and fuelwood, with gross tonnage ranging from 50 to 150 tons. The second type was the “Timber Tongkang”, used exclusively for carrying saw-logs with gross tonnage of over 150 tons. The hull of both types of tongkangs was described as a “heavy, unwieldy, wall-sided affair, full in the bilges, with a long straight shallow keel, angled forefoot and heel, a sharp raked bow and a transom stern” (Gibson-Hill, 1952:85–86).

The modifications to the tongkang included a rectangular rudder pierced with diamond holes, a square gallery projecting over the stern of the tongkang, and a perforated cut-water.

The “Singapore Trader” was 60–90 feet long with a breadth of 16–33 feet and a depth of only 8–10 feet whereas “The “Timber Trader” was much larger at 85–95 feet in length and had a breadth of 30–33 feet and a depth of 12–15 feet.

The small vessels had two masts – the main-mast and the foremast, whereas the large vessels i.e. those above 50 tons stepped three masts; that is, the main-mast, the fore-mast and the mizzen-mast. In the 1950s, the main-sail costed between $250–$300 each, while smaller sails were priced at $150–$200 each.

Tongkangs were full utility vessels and about four-fifths of the space on a tongkang was used for storing cargo. A small area of deck at the stern of the ship, which was roofed, was used as the crew’s living quarters in the form of two small cubicles. The rest of the roofed area was taken up by the kitchen. A shrine to the goddess Mazu, the guardian of seamen was always affixed on every vessel.

Capital and Recurrent Costs

In the 1950s, a new tongkang below 50 tons cost between $10,000 and $15,000 to build while those above 100 tons ranged from $70,000 to $80,000. Very few tongkangs were built by about late 1958 because of the trade recession which began in early 1957, and also the declining importance of tongkangs as cargo carriers. The few that were built were below 50 tons, for service as charcoal and fuelwood carriers.

Tongkangs were overhauled about three times a year, when barnacles were cleared from the hulls, minor repairs made and generally a spring-cleaning given, at the cost of between $50 and $200 depending on the size of the ship. Sails were changed once a year, unless they were badly torn as a result of tongkangs being lashed by storms.

Major repairs were carried out at periods varying from five to 10 years, involving the replacement of timber of some portions of the ship, changing masts and other costlier repairs. Properly maintained, tongkangs could last up to 50 years, though most vessels were scrapped after 30 years of service. Naturally the rate of maintenance depended on the volume of trade handled by tongkangs as seen during the Korean War boom, when tongkangs were regularly serviced. However by 1957, overhauling dropped to about twice a year, owing to their declining importance, and most were slowly being scrapped, without being replaced.

The Tongkang Hub

The centre of the tongkang industry was that part of the island bound by Kallang Road, Crawford Street, Beach Road and Arab Street where owners of tongkangs had their business premises. This centre was a compact area where seamen could be recruited and vessels chartered without difficulty.

“Timber Tongkangs” anchored and unloaded their cargo of logs into the sea, off Beach Road, the main anchorage for tongkangs until the building of the Merdeka Bridge in 1956. Logs were towed into the Kallang Basin, where they lay submerged in water until required by sawmills, resulting in a distinctly unpleasant smell in the vicinity.

All other tongkangs unloaded their cargo of charcoal and fuelwood, poles, planks and sago at Tanjong Rhu. Though Beach Road was the hub of the industry, it was gradually replaced by Tanjong Rhu, where warehouses and wharves were constructed to accommodate the tongkang trade.

Tongkangs were used for coastal and inter-island trading, sailing to Indonesia, South Johore, Malacca, Perak and Sarawak. Much of the trade with Indonesia was mainly in the Riau and Lingga Archipelagoes which lay to the south and southeast of Singapore, the east coast of central Sumatra, namely Siak and Indragiri, and some of the major islands off the Sumatran coast.

The Trade of the Tongkangs

The trade handled by tongkangs was part of the larger and extremely important volume of trade between Singapore and Indonesia,3 Singapore’s best trading partner and valuable customer in the use of entrepot facilities up to the end of 1957, when the Indonesian Government began to adopt policies to encourage direct trading with other countries, bypassing Singapore. However, in 1957, imports from Indonesia to Singapore amounted to S$1,099,478 945 while exports to Indonesia were valued at $250,274,272.4 Indonesia ranked highest in her exports to Singapore which were mainly reexported. The value of Indonesian imports into Singapore was higher than the combined value of imports from the United Kingdom and the United States – two major countries.

Similar to the faster and more efficient means of sea-transport, tongkangs also played their part in carrying raw material into Singapore, to be processed and re-exported, thus adding to the national income of the island. The major items of the tongkang trade were fuelwood and charcoal, wood in the round, mainly saw-logs and poles, sawn timber, rubber and raw sago, all non-perishable in nature for which timing was relatively unimportant, unlike for foodstuffs and essential raw materials such as rubber. Other produce carried on tongkangs included copra, coffee, tea, and spices. Being slower than steamships and freighters, tongkangs were particularly suited to carry non-perishable cargo more competitively than steamships and other faster means of sea-transport. These products were carried to attractive freight earnings for tongkang operators when there was a shortage of space on the steamships.

Demand, Supply and the Impact on Tongkang Cargoes

It is interesting to note that the earnings of the tongkang trade were affected by world events and politics such as the Korean War in the 1950s, the Suez Canal crisis in 1956 which impacted on demand, supply, and prices of goods and freight charges.

Local developments such as the housing shortage, the building of Singapore Improvement Trust flats and the shift to use of gas, power and kerosene as cooking fuels from charcoal and fuelwood also affected the tongkang trade. Both charcoal and fuelwood were then facing competition from gas, power and kerosene as cooking fuels. When people of the lower income groups, who were important users of fuelwood and charcoal, occupied Singapore Improvement Trust flats, they were compelled to use either gas or power for cooking. Other households were also increasingly switching to kerosene for cooking purposes. To meet the challenge, fuelwood and charcoal dealers argued that kerosene, besides being a fire hazard, was unsuitable for cooking. They claimed that food cooked over kerosene fire had an unpleasant smell and was not as nutritious as food cooked over charcoal fire! Though households were switching to kerosene, two major users of charcoal and fuelwood, namely coffeeshops and restaurants, still used charcoal and firewood, as they were cheaper than kerosene.

Elsewhere overseas, techniques to turn wheat or maize into starch powder caused the export of sago to fall – sago being one of the items commonly carried by the tongkangs. European manufacturers of starch flour made out of maize, had the additional advantage of being nearer the export markets. As a result demand for and price of sago fell.

Similarly, Singapore sawmills consumed less saw log imports from Indonesia when overseas demand for sawn timber, and consequently their prices, fell.

The Demise of the Tongkang

The tongkang industry depended on the demand for the type of cargo a tongkang carried. Unfortunately there was a definite falling trend, with the local housing situation at the time and the low volume of demand from overseas markets. Besides, the demand for tongkang labour was a derived demand, being dependent on the volume of trade handled. The low rate of new recruitment into the tongkang labour force indicated that it was contracting as men who retired were not correspondingly replaced.

It was unlikely that tongkangs could have switched to carrying other types of cargo. Thus the then future of the tongkang industry was bleak. According to the Annual Report of the Registry of Commerce and Industry and the Registry of Ships, Native Sailing Vessels dropped from 399 in 1954 to only 299 in 1957.

It was obvious that the tongkang trade was losing out to modernisation, development and shipping technologies of the late 1950s and 1960s onwards.

The eventual decline of the industry was clearly seen in the increasing number of vessels which were being scrapped annually. As few new vessels were built, the size of the tongkang fleet in Singapore thus contracted, signalling the gradual demise of an old practical industry overtaken by modern shipping and port development.

Excerpted from “Tongkangs, the Passage of a Hybrid Ship” in Maritime Heritage of Singapore, pp. 170-181, ISBN 981-05-0348-2, published 2005 by Suntree Media Pte Ltd, Singapore. Call No.: RSING 387.5095957

By Ngiam Tong Dow, based on a university dissertation ca. 1957; Edited by Aileen Lau Captions and images reproduced from Maritime Heritage of Singapore

REFERENCES

C. A. Gibson-Hill, “Tongkang and Light Matters,” Journal of the Malayan Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society 25, no. 1 (158 (August 1952): 85–86. (From JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website)

D. G. E. Hall, A History of South-East Asia (London: St. Martinʹs Press, 1955). (Call no. RCLOS 959 HAL)

NOTES

All statistical data from Statistics Department, Singapore, Annual Imports and Export, I. & E.

-

Nanyang = southern ocean. Also used by Chinese migrants to mean Southeast Asia. ↩

-

Information from Mr Chia Leong Soon, Secretary of the Singapore Firewood and Charcoal Dealers’ Association for this information. Read and Ord Bridges are known to the Chinese as the “fifth” and “sixth” bridge respectively. A large Chinese boatyard is situated in Kim Seng Road along the upper part of the Singapore River facing the former Great World Cabaret (today redeveloped as the Great World City complex). ↩

-

Unless otherwise stated, the statistical data used in this chapter, were compiled from unpublished material in the Statistics Department, Singapore, and cited with the kind permission from the Chief Statistician. ↩

-

Malayan Statistics: External Trade of Malaya, I & E 3, 1957. ↩