Descendants of Dragons and Fairies: Vietnamese History Before French Colonisation

We tend to associate Vietnam with the horrific battles at Dien Bien Phu and the Vietnam War, but there is much more to Vietnamese history. This essay provides a historical sketch of Vietnam up to the 19th century, before French military forces overran Indochina and transformed it into a colony.

From Myth To History

Traditionally, ethnic Vietnamese trace their ancestry back to a “royal” line known as the Hung kings (Hung Vuong) whom they believe ruled Van-Lang, said to be Vietnam’s earliest kingdom. According to Vietnamese folklore, the Hung Vuong were descendants of dragons and fairies. A sea dragon lord, known as Lac Long Quan, was said to have fathered a hundred children by a princess of the mountains, named Au Co.

It was to be a sad ending for the odd couple, however. Having come from two different worlds, they parted ultimately. Lac Long Quan returned to the watery depths with 50 of their children, while Au Co settled in an area, which is the present-day Red River Delta, with the remaining 50, one of whom became the first Hung king. The story of Lac Long Quan and Au Co has certainly become so deeply entrenched in the Vietnamese popular imagination that a shrine dedicated to them was erected in Valli Phuc province, 50 km northwest of the modern-day Vietnamese capital of Hanoi, and is maintained to this day.

The last Hung king is said to have been overthrown by King An Mang (An Duong Vuong), who is according to American historian Keith Taylor, “the first figure in Vietnamese history documented by reliable sources”. (Taylor, 1983:20–21). Notwithstanding this, as pointed out also by Taylor, much of what is known about his reign is shrouded in myth. Based in his great citadel of Co-loa, he reportedly defeated the last Hung ruler and renamed the Vietnamese lands Au Lac. Legend has it that King An Duong’s polity was safeguarded by a golden turtle (presumably the incarnation of Lac Lang Quan), who presented one of its claws to him, which he used to make a magical crossbow. The capture of this crossbow by an enemy, as the story goes, led to his eventual downfall.

That enemy was Zhao Tuo, known to the Vietnamese as Trieu Da, an official based in what is today south China. Upon defeating King An Duong, Zhao Tuo proclaimed himself the king of Nan Yue (Nam Viet). The history of Nan Yue is discussed with great detail in Zhang Rongfang’s and Huang Miaozhang’s Nan Yue Guo shi (The History of the Nan Yue/Nam Viet polity). Carefully researched and rather comprehensive in scope, this book sheds light on the different aspects of this ancient political entity, including its hitory, economy, society and culture. The Nan Yue polity lasted for almost a century before being destroyed by the armies of a far mightier power - China’s Han dynasty.

Under Imperial China’s Grip

In 111 BCE, the Chinese Han dynasty invaded northern Vietnam and stayed. This event marked the beginning of imperial Chinese political presence in the area; from then until 939 CE, successive states/dynasties in China laid their claims on the northern half of Vietnam. During these 13 centuries, Chinese administrators dispatched to the area found themselves having to cope with periodic uprisings from its inhabitants. The people who led these rebellions were subsequently delfied and worshipped after their deaths, while their historical acts - specifically their resistance against the Chinese - were transformed into heroic tales of ‘saints’ to be emulated by future generations.

The events during this period of Chinese occupation (Bac Thuoc in Vietnamese, meaning “belonging to the North”, the ‘North’ here referring to China) constitute the bulk of historian Keith Taylor’s work The Birth of Vietnam. His study also includes prehistoric period. Having researched meticulously into both Chinese and Vietnamese primary sources, Taylor not only brings historical characters to life in this highly detailed work, but also challenges the view of pre-10th century Vietnamese history being a mere offshoot of Chinese history. The arguments he set forth in this book seek to bring out early historic Vietnam as a somewhat unique entity that strove to preserve its identity in spite of overwhelming Chinese political and cultural influences.

The Age Of Emperors

The key figure responsible for the release of imperial China’s grip over Vietnam was a Vietnamese general named Ngo Quyen, who in 93B CE defeated troops sent by a southern Chinese polity in a decisive battle. The showdown took place at Bach-clang River, an estuary marking the entrance to the Red River Delta. Before the Chinese military fleet arrived, Quyen ordered his men to plant large poles with sharpened tips in the river bed. The heights of the poles were kept to just short of the water level at high tide, so that they would not be visible to the enemy as their ships sailed in. As the tide receded, the bottoms of the Chinese flotilla were ripped open by the sharp ends of the poles. Caught helplessly in the river, the Chinese troops suffered huge casualties as Ngo Quyen’s own army attacked. A few months later, the general himself took the title of “King” (Vuong).

In the spring of 939 CE, the year that marks the end of direct Chinese rule over northern Vietnam, Ngo Quyen merely proclaimed himself “King “. It would be another three decades before someone went a step further to take the title of “Empero” (de). That person was Dinh Boh Linh, who founded the Dinh dynasty in 966 and named his state Dai Co Viet. From then until the first half of the 20th century, Vietnam would have her fair share of emperors like her northern neighbour, China.

Oscar Chapuis’ A History of Vietnam from Hang Bang to Tu Duc provides brief but colourful sketches of these Vietnam’s “Sons of Heaven”, and is an excellent starter for any beginner to pre-modern Vietnamese history. Researchers who wish to plunge directly into first-hand primary archival material related to Vietnam’s early dynasties may refer to two other publications. The first, titled Epigraphie en chinois du Vietnam, is a joint collaboration between Vietnam’s Han Nom Institute and France’s Ecole francaise d’Extreme-Orient (EFE0). Both institutions have in their holdings a combined total of over 50,000 epigraphic material. The inscriptions found on 27 epigraphs from the Chinese occupation period to the Ly dynasty are featured in volume. The second resource, Yuenan Shilun: Jinshi Ziliao Zhi Lishi Wenhua Bijiao (Essays on Vietnamese History and Culture Based on Epigraphic Materials) is a collection of analytical essays on the Ly and Tran dynasties, based on epigraphic sources from the two dynasties.

Vietnamese rulers were well aware that China’s monarchs would continue to keep a close watch on them, and while Chinese rule had been successfully repelled, it could return. Therefore, some form of diplomatic relationship had to be established, and the Vietnamese monarchs did so by dispatching envoys to China. The arrangement commonly known as the tribute system, was vastly different from what was practised between nation-states. From Imperial China’s point of view, the relationship was to be an unequal one; in her eyes, she was the suzerain, and Vietnam a vassal. Vietnam was to pay tribute to China.

Liam C. Kelley’s Beyond the Bronze Pillars: Envoy Poetry and the Sino-Vietnamese Relationship looks at this relationship through the poems of the Vietnamese envoys. The conclusions he draws in his book are a refreshing departure from the convention — that the Vietnamese always strove to assert their cultural distinctiveness and political equality vis-a-vis the Chinese. Contrary to this belief, Kelley argues that at least from the perspective of the Vietnamese envoys, there was “a profound identification with the cultural world which found its center at the Chinese capital” as well as an acceptance of “their kingdom’s political subservience in that same world” (Kelley 2005:2).

The dynasties that were to follow the Dinh were the Ly (1009–1225), Tran (1225–1400) and Ho (1400–1407). China under the Ming dynasty succeeded in conquering northern Vietnam in 1407 but its occupation lasted only two decades. In 1427, after the Ming decided to pull out of northern Vietnam, the monarchical system was restored under the Le dynasty. This dynasty readched its apogee (Airing the reign of Le Thanh Tong (r. 1460–1497), who successfully expanded the Vietnamese empire southwards into the territories of its southern neighbour - a polity known as Champa.

Champa

It is difficult to ignore the discussion on the polity of Champa when one talks about the history of Vietnam. Occupying the central coast of what its modern-day Vietnam, what can be known of Champa is essentially based upon evidence drawn from inscriptions as well as Chinese sources. The Cham people are ethnolinguistically Malay and their culture was subjected to a great degree of Indian influence.

Champa’s relationship with its northern neighbour dated back many centuries. Historians have reconstructed interesting histories of inter-marriages and warfare taking place between the two polities over the centuries. One episode tells of how a Vietnamese princess, who was married off to a Cham ruler, was coerced to throw herself on her husband’s funeral pyre after his death - a practice attuned to Hindu tradition. The Vietnamese were not prepared to see their princess go up in flames, so they sent an army to rescue her. The rescue attempt was successful, but relations between the two polities worsened as a result. As for the princess, after a brief fling with a Vietnamese intellectual, she ultimately opted for a reclusive life as a Buddhist nun.

A seminal work on Champa is that by the late French historian Georges Maspero, and an English translation of the French text has been made available by Thailand’s White Lotus Press. Entitled The Champa Kingdom: The History of an Extinct Vietnamese Culture, the book traces the history of the Cham from its beginnings to its final destruction in 1471, when Vietnamese armies sent by Le Thanh Tong overran the Cham capital of Vijaya. Thereafter, Champs was incorporated permanently as part of Vietnamese territory.

Late Imperial Vietnam: Division and Reunification

By the first half of the 16th century, the Le dynasty had weakened to such an extent that it fell victim to a usurper. In 1527, an official named Mac Dang Dung arranged the death of the reigning monarch Le Cung Hoang, and proclaimed himself emperor of a new dynasty and occupying the Le capital of Theng-long (modern-day Hanoi). After this debacle, surviving members of the Le enlisted the help of a powerful warlord named Trinh Kiem to restore their dynasty. In 1592, they finally succeeded in driving the Mac out of Thang-long. However, the Le found themselves at the mercy of Trinh Kiem’s successors, who became known as the “Trinh Lords”. The latter were the actual power holders.

The Trinh never managed to capture the southern part of Vietnam (formerly Cham territory); this came under the control of yet another powerful family the Nguyen. At first, the Nguyen and the Trinh had cooperated with each other against a common enemy the Mac. However, once the Mac had been driven out, both became rivals. Vietnam had in fact been divided into two, though both warlord families acknowledged the legitimacy of the puppet Le government.

Under the Nguyen. Vietnam’s southern border was extended even further, this time all the way to the Mekong Delta, seized from the Cambodian kingdom of Angkor during the late seventeenth century. Li Tana’s book Nguyen Cochinchina: Southern Vietnam in the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries is an in-depth study of the economy and society of south Vietnam under the Nguyen regime. She begins her analysis with an examination of the demographics of the territory and of the ways the Nguyen lords impacted upon the settlers there. Li does not simplify focus on the indigenous aspects of the area, but also looks at the contributions made by foreign merchants (Chinese, Europeans and Japanese) towards its economy.

The period of territorial division was ended by what became known as the Tay Son movement, which took place in the late 18th century. In 1771, three brothers from the village of Tay Son raised the banner of revolt against the Nguyen. They managed to overthrow the latter in 1785, and next advanced northwards onto Thang-long, the seat of government and the stronghold of the Trinh. By 1786, all of Vietnam was practically theirs, and two years later, Nguyen Hue, the eldest brother, ascended the throne as Emperor Quang Trung. The last Le ruler fled to China, and appealed to the Manchu emperor Qianlong to send an expedition into Vietnam to restore him to the throne. Qianlong did send his armies into Vietnam, but his troops were badly defeated by the Tay Son soldiers. The Le dynasty had come to an end.

The Tay Son dynasty itself was short-lived; it began to crumble after Nguyen Hue’s sudden death in 1792. In 1802, Nguyen Anh, the last surviving member of the Nguyen house who had seized control of the south, marched his troops northwards and captured Thang-long. Four years later, he proclaimed himself Emperor Gia Long and changed the dynastic name to Nguyen; it was to be Vietnam’s last dynasty.

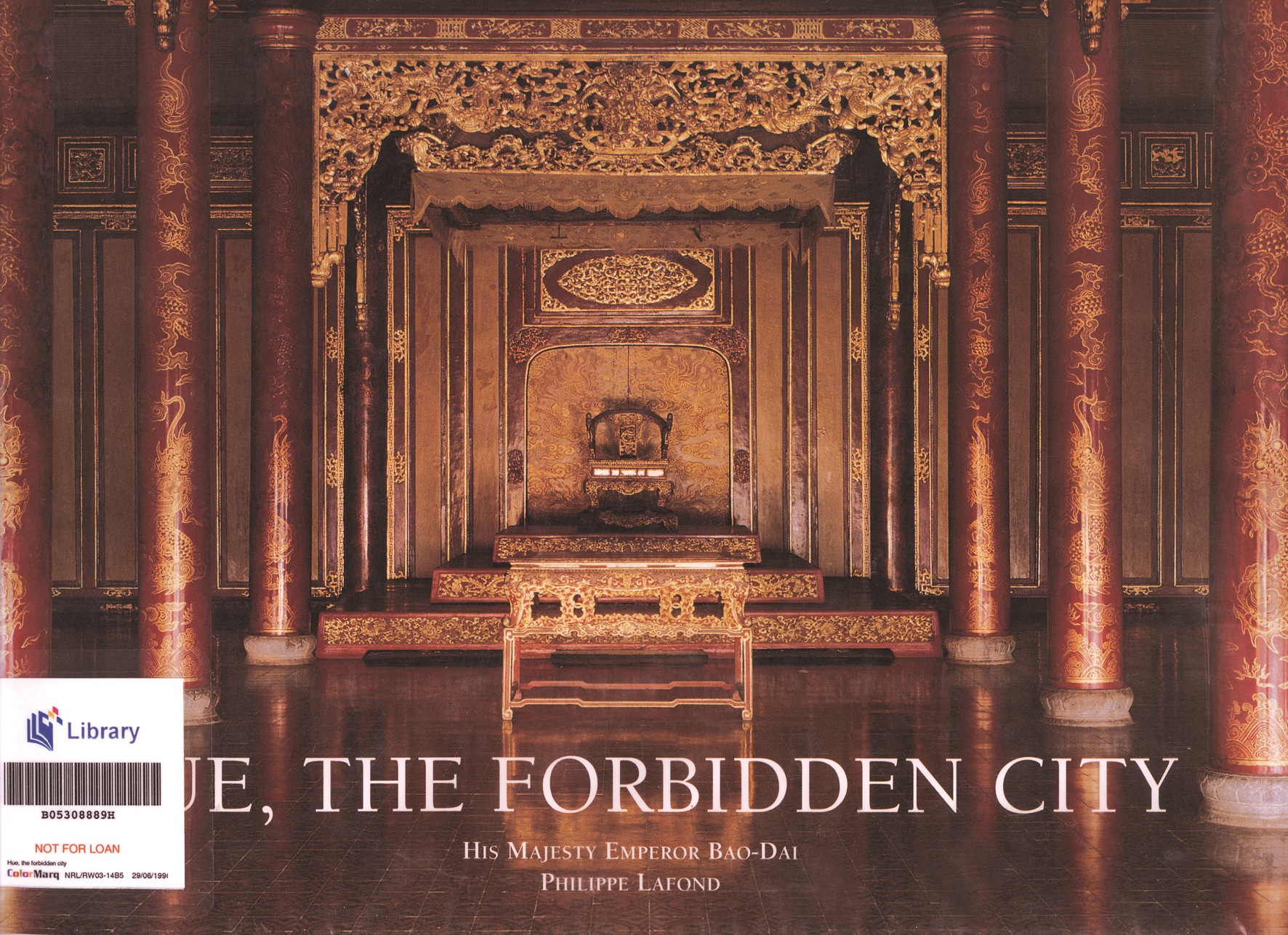

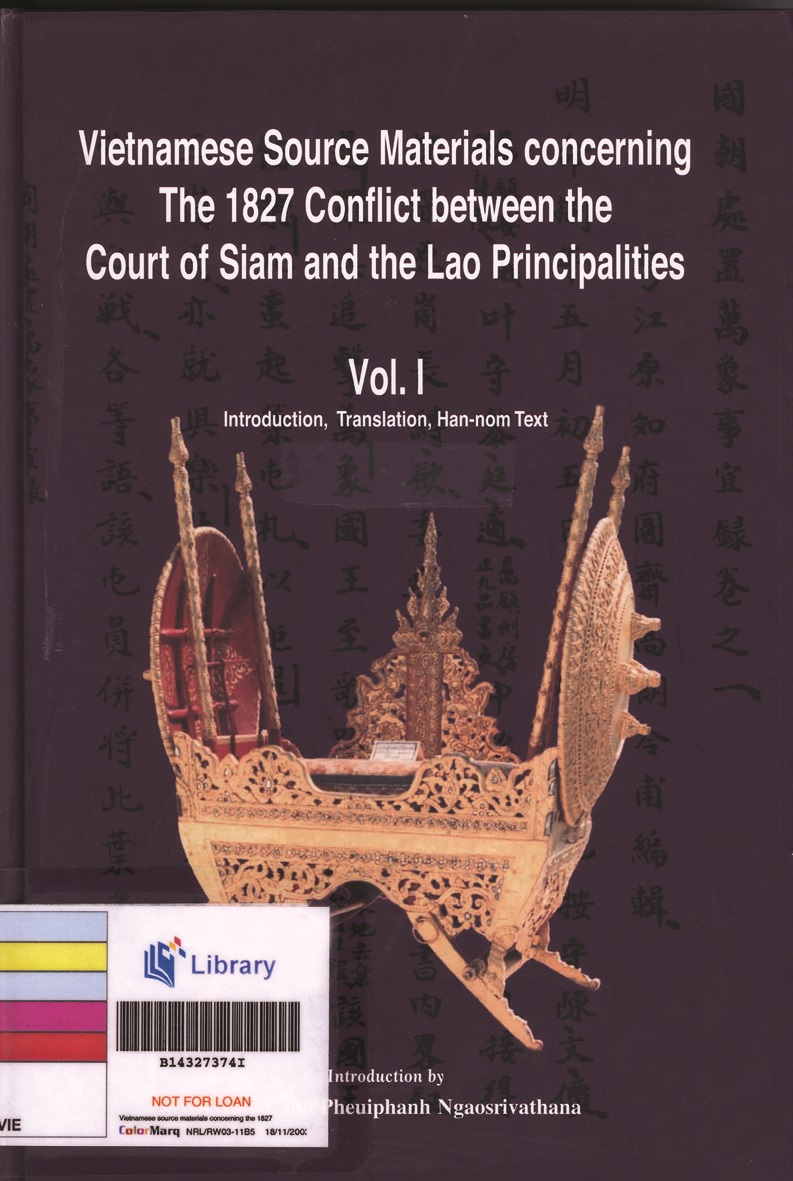

There are a few titles about the Nguyen dynasty (1802–1945) in the Library, and two will be mentioned here. The first, entitled Hue, The Forbidden City is an enticing pictorial spread on the dynasty’s imperial capital situated in central Vietnam. Compiled by Bao Dai, Vietnam’s last emperor, and French photographer Philippe Lafond, this work is a good blend of colourful photographs and well-researched text. The second, a two-volume series, Vietnamese Source Materials Concerning the 1827 Conflict between the Court of Siam and the Lao Principalities, contains English translated Vietnamese primary documents related to a war that erupted between Laos and Siam in which Vietnam was deeply involved. The documents not only provide some insight into the workings of Nguyen foreign policy, but also give readers a sense of the geopolitical dynamics in early 19th-century mainland Southeast Asia.

Reference Librarian

Lee Kong Chian Reference Library

National Library

REFERENCES

Bao Dai and Philippe Lafond, Hue, the Forbidden City (Paris: Edition Menges, 1995). (Call no. RSEA 959.703 LAF)

Geng Huiling 耿慧玲, Yue’nan shi lun: jin shi zi liao zhi li shi wen hua bi jiao 越南史论 : 金石资料之历史文化比较 [A history of Vietnam: A historical and cultural comparison of inscriptions and stone materials] (Taibei 台北 : Xin wen feng chu ban gong si 新文丰出版公司, 2004). (Call no. Chinese RSEA 959.7 GHL)

Georges, Maspero, The Champa Kingdom: The History of an Extinct Vietnamese Culture, trans. Walter E.J. Tips (Bangkok: White Lotus Press, 2002). (Call no. RSEA q959.703 MAS)

Keith Weller Taylor, The Birth of Vietnam (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1983). (Call no. RCLOS 959.703 TAY)

Li Tana, Nguyen Cochinchina: Southern Vietnam in the Seventeenth and Eighteen Centuries (New York: Southeast Asia Program, Cornell University, 1998). (Call no. RSEA q959.703 LI)

Liam C. Kelley, Beyond the Bronze Pillars: Envoy Poetry and the Sino-Vietnamese Relationship (Honolulu: Association for Asian Studies; University of Hawaii Press, 2005). (Call no. RUR 303.4825970510903 KEL)

Mayoury Ngaosyvathn and Pheuiphanh Ngaosyvathn, eds., Vietnamese Source Materials Concerning the 1827 Conflict Between the Court of Siam and the Lao Principalities: Journal of Our Imperial Court’s Actions With Regard to the Incidence Involving the Kingdom of Ten Thousand Elephants, 2 vols. (Tokyo : Centre for East Asian Cultural Studies for Unesco, the Toyo Bunko, 2001). (Call no. RSEA 959.403 VIE)

Oscar Chapuis, A History of Vietnam: From Hong Bang to Tu Duc (Westport: Greenwood Press, 1995). (Call no. RSEA 959.7 CHA)

Phan Van Cac and Claudine Salmon, eds., Epigraphie En Chinois Du Vietnam De!’Occupation Chinoise a La Dynastie Des Ly [越南汉喃铭文汇编], vol. 1 (Paris: Ecole francaise d’Extreme-Orient & Han Nom Institute, 1998). (Call no. RSEA 959.703 YNH)

Zhang Rongfang 張榮芳 and Huang Miaozhang 黄淼章, Nan yue guo shi 南越国史 [The history of the Nan Yue/Nam Viet polity] ([Guangzhou] [廣州]: Guangdong ren min chu ban she 廣東人民出版社, 1995)