Conquering Everest, the World’s Tallest Mountain

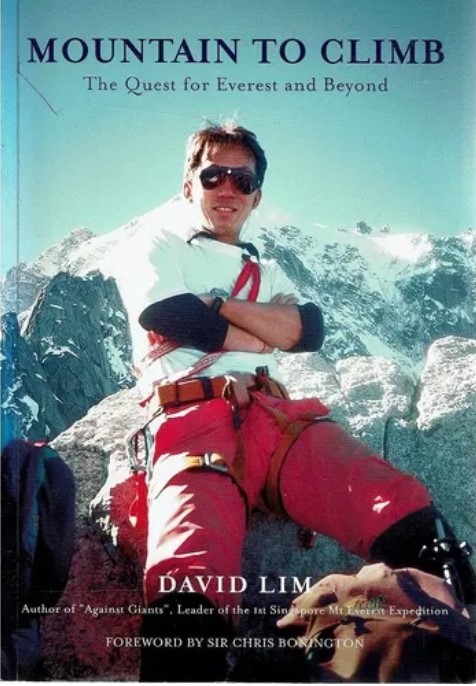

David Lim led the first Singapore expedition team that successfully scaled Mount Everest on 25 May 1998. This is an excerpt from his book, Mountain to Climb: The Quest for Everest and Beyond.

By David Lim

On 29 May 1953, New Zealander mountaineer and explorer Edmund Hillary and sherpa Tenzing Norgay made history by becoming the first people to summit Mount Everest. Straddling the border of Nepal and Tibet, the world’s highest peak has borne witness to both great accomplishment and tragedy.

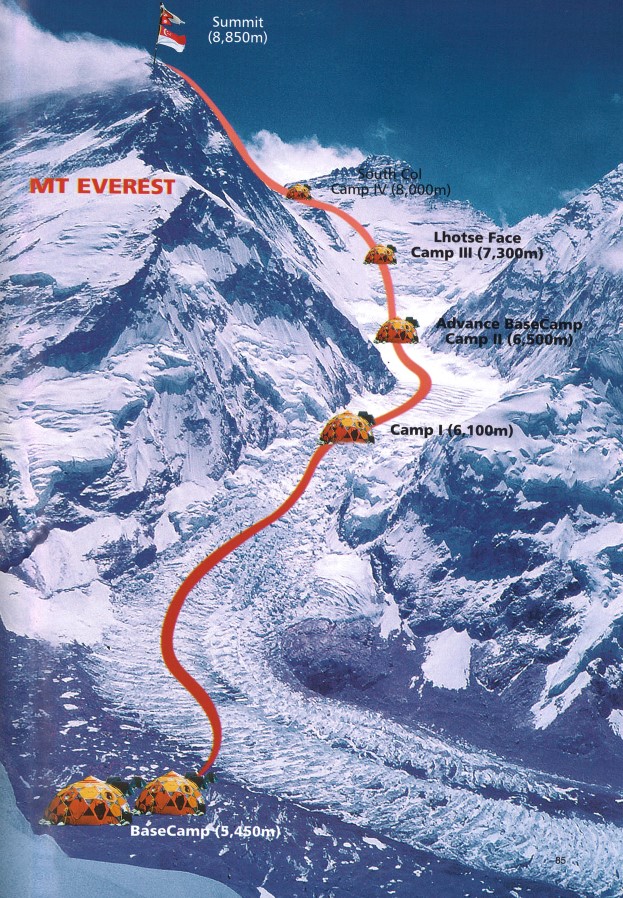

Standing at 8,849 m (29,032 ft), the ascent up Everest1 requires years of preparation and training. The climb is treacherous no thanks to heavy snow, slippery slopes, strong winds and avalanches. At such high altitudes, climbers are also susceptible to serious conditions like pulmonary edema, cerebral edema, blood embolisms, frostbite and altitude sickness.2

In May 2023, Singaporean Shrinivas Sainis Dattatraya, 39, went missing during an attempt to climb Everest. He had reached the summit on 19 May but developed high-altitude cerebral edema and told his wife he was “unlikely to make it down the mountain”. Attempts to locate Shrinivas were unsuccessful and, in an Instagram post, his wife paid tribute to her husband noting that “…he lived fearlessly and to the fullest. He explored the depth of the sea and scaled the greatest heights of the Earth. And now, Shri is in the mountains, where he felt most at home.”3

This event comes 25 years after mountaineer and climber David Lim led the first Singapore expedition to successfully conquer Everest.4 On 25 May 1998, Outward Bound Singapore instructor Edwin Siew became the first member from the team to reach the summit. He was followed by systems analyst Khoo Swee Chiow half an hour later. Lim himself did not make it to the summit due to an injury sustained during the climb.

Unfortunately, one week after the team’s return, Lim was stricken with Guillain-Barré syndrome, a rare nerve disorder. Within days, his limbs were paralysed and his respiratory system shut down. Unable to speak, move or breathe, Lim endured 42 days in intensive care before his condition stabilised. He then spent six months recuperating in the hospital, where he had to relearn basic skills such as writing, dressing himself and walking. Undeterred, Lim returned to mountaineering and has led more than 15 climbing expeditions since 1999, including the first all-Singaporean ascent of Aconcagua (6,961 m) in the Andes Mountain range in Argentina.

In 2023, Lim donated 140 items to the National Library Board, comprising mostly raw footage of the first Singapore Mount Everest expedition, the Singapore-Latin America expedition and various other climbs. He also donated a set of curated digitised footage extracted from the raw footage of the 1998 expedition.

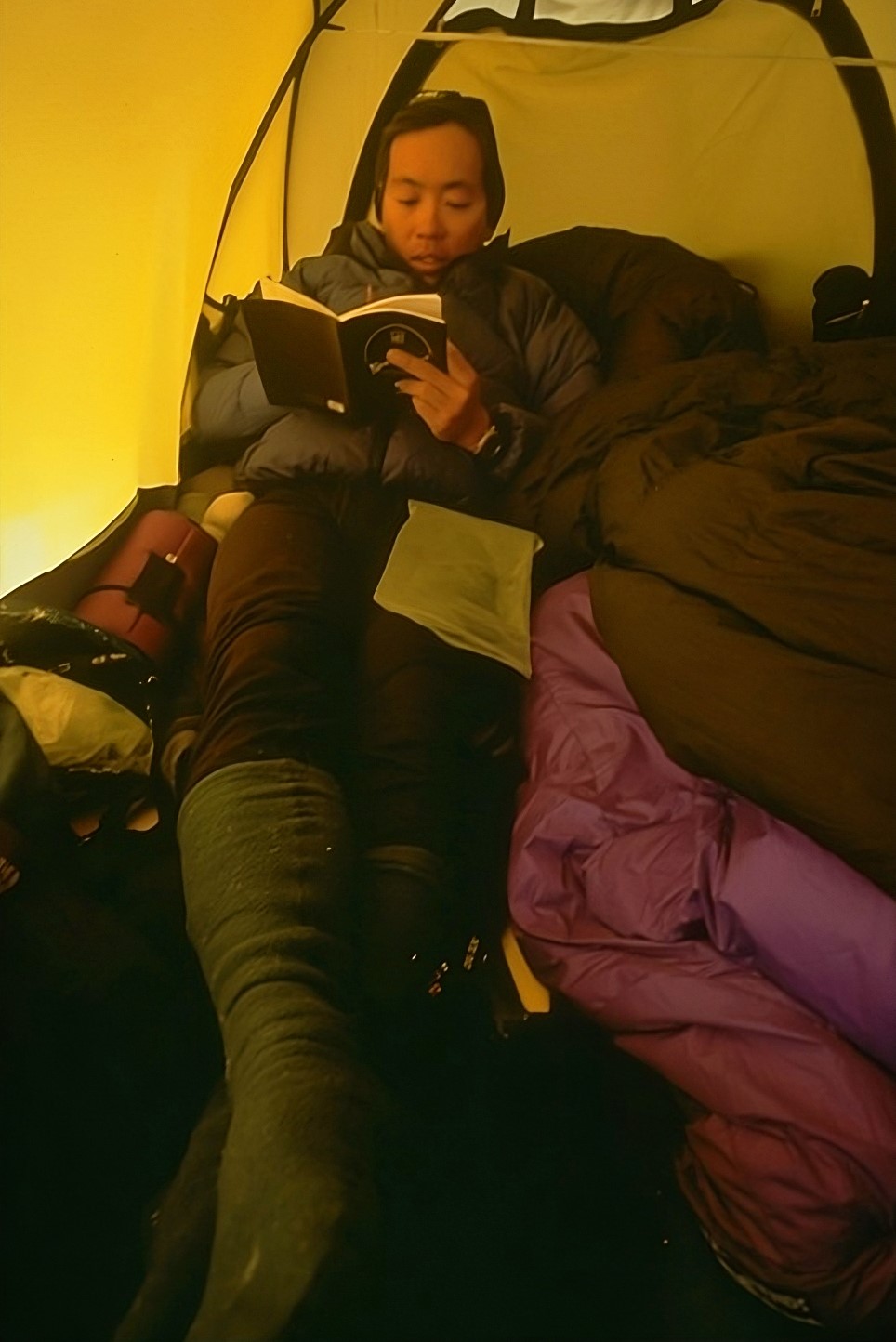

Among the donations is a signed copy of his book, Mountain to Climb: The Quest for Everest and Beyond (1999). The book is a personal account of the Singapore team’s quest to climb Everest, including the failures, heartbreak and sacrifices. To mark the 25th anniversary of the Everest climb, BiblioAsia is publishing an extract of Chapter 19 of the book. In it, Lim recounts the events immediately leading up to the team’s first attempt to summit Everest on 19 May 1998.

I met up with Michael Strynoe, the Dane who was climbing unsupported on Everest. With him was Thomas Sjogren, a wealthy Swedish paper magnate, who was climbing Everest with his wife. They had had two previous unsuccessful attempts on Everest. As smaller, independent parties, they were reliant on larger teams to kick in a trail to the top and to fix the route. Everything depended on the weather. We promised to radio Thomas later that night with a weather update. The afternoon air was fairly frigid and I began to have a prolonged coughing fit. Retiring to my tent for some rest, I awoke to an excruciating pain on my left side. It was 6 pm and the Emir’s [referring to Colonel Bruce Mackenzie Niven, the Singapore team’s base camp manager] voice came over the airwaves. I reached for the radio near my left thigh but could not reach it. The slightest effort sent sharp stabbing pains into my back. The pain radiated from my back and fanned outwards. It was as though someone had stuck a knife in my side and was twisting the blade back and forth.

Cursing at this turn of events, I gave up trying to reach for the radio. Justin [Lean], who held another radio, picked up the call. I shared the tent with Edwin [Siew] that night, he looked quite concerned as I lowered myself into my sleeping bag, wincing at the severe pain. It was many times more painful than any of my “cracked rib” incidents. At dinner, I laid out the options. It was important that the team be in a high enough position to push for the top, given the very small weather window. Confirmation of the storm would still allow them to retreat back to BC [Base Camp] in time. So, it was important that the summit team go up to C3 [Camp 3]. It might be the only chance. Using the popular American saying, I quipped:

“The game ain’t over until the fat lady sings.”

I lay in my tent, sleepless for most of the night, thinking about how that afternoon’s coughing fit had either torn a ligament or a cartilage. A full dose of Voltaren painkiller was ineffectual. I awoke the following morning, May 16, hoping for the best. Another stab of pain doubled me over. I sat up, holding my side and turned to Edwin.

“Edwin, you should get prepared. You’re going up.”

On the afternoon of May 17, I met up with various team leaders at [Bob] Hoffman’s C2 [Camp 2] mess tent. Hoffman had had the luxury of small folding chairs (we used rocks) and the issue of the weather was discussed. The snowfalls we had experienced were local conditions and not easily captured on the weather reports which focused on larger areas. Big mountains like Everest and K2 can and did influence weather patterns within their area of influence. The weather forecast from [a specialist in] Bracknell was based on a large amount of information fed into a computer which then ran simulations. This was done twice a day: once at 0600 GMT and another time at 1800 GMT. The more times this was done, the more accurate the prediction became.

It was a fairly tense meeting, punctuated only by some jokes between Michael, the Dane, and members of Hoffman’s American team. Hoffman’s team was incomplete and members were still trickling in. At the table was Mark Cole, Bob Hoffman and PY Scaturro, Hoffman’s lead climber. Our radios served as tools to allow for the conference. Other representatives were Andy Lapkass from Henry [Todd]’s team, Dave Walsh, head guide for the Himalayan Kingdom’s team and Inaki Ochoa, the Basque soloist, who, like Michael, was climbing unsupported. lnaki had hoped to make a quick ascent of Lhotse, Everest’s rarely climbed neighbour. He was climbing alone and had made two previous attempts in the preceding weeks. Saying his stamina was pretty good was an understatement.

Henry’s crisp, upper-crust voice came over the radio. The news was not encouraging. I imagined Henry, far away at BC, reading the crucial fax from Bracknell.

“The cyclone over lndia is holding steady over Madras but it may move north. If it does so, it will reach us in 72 hours. Bracknell have said that if it does, we will have 48 hours’ notice before it hits. It will either head directly for us or swing to the right into Bangladesh and Thailand.”

Henry had been asking for any additional help worldwide. Our own Singapore Met information was added to a growing body of information. What was difficult was the actual interpretation of the data. It was a critical moment for all the teams on the mountain.

Discussions followed. The 48 hours’ notice was crucial. It was the minimum amount of time needed to evacuate the mountain. Teams began to get mobilised. This looked like the only summit window of the whole season. From C2, climbers needed a day to get to C3 and then another day to get to C4 [Camp 4] at South Col [col is a Welsh term referring to a saddle or pass between mountains]. At the rate our lads were doing, they would reach South Col on May 18, the following day. Hoffman was more circumspect. He was gambling that the good weather would hold. In any event, his team was only assembling on May 17. It was unlikely that they would make the summit on May 19. Most of the other teams had also come to the conclusion that a May 19 summit day was the best chance of success and avoiding the cyclone. Bad weather on a mountain like Everest was a deadly serious event. A huge dump of snow would end the season. The accompanying winds would also rip our tents apart and the icefall would be a chamber of horrors.

The game was on and I had to balance the risks of the team being stuck up high and keeping our resources together should a second attempt be required. But there was not a snowball’s chance in hell I would have jeopardised any member unnecessarily for the sake of a summit. The 48 hours’ notice would give them time to retreat to BC even if they were on South Col. The team made good progress to C3 and we settled in for another long night.

The radio report on the morning of May 18 from the summit team showed that all had gone smoothly. They had slept using some bottled oxygen and were now en route to the Col. with an oxygen tank each. The LSE bottle would provide a modest flow of oxygen and have enough left over to use as an aid to sleep. At C2, Mok [Ying Jang] and I bid the sherpas a safe climb. The sherpas would climb, in a single day, to South Col. They never slept at C3. They wore smiles, but their eyes, darting left and right, reflected what they really felt. I had had that feeling before – the palm-moistening sensation as a summit push began.

By 10 am, we saw a line of about 50 ant-like figures crossing the Lhotse face headed towards the Geneva Spur and the Col. Mok became concerned about the risk of bottlenecks on summit day. He made a bad joke about his services being needed if the events of 1996 were repeated. [Our] climbers would pair up with the sherpas for the summit climb – [Man Bahadur Tamang, or MB] with Justin, Lhakpa [Tshering] with Robert [Goh], Dawa Tshering with [Rozani], [Khoo Swee Chiow] with Kami Rita and Edwin with Fura [Dorje]. At South Col, Pasang Gambu and Nawang [Phurba] would be sipping on oxygen, ready to respond to any emergency. Dorje [Phulilie] and Phurba would spearhead the rope laying of the route on summit day.

The day was eventful. At about noon, long after the snake-like queue of climbers had disappeared from view, a sherpa ran up to our camp, asking for medical supplies. He was from the commercial group, Himalayan Kingdoms. A sherpa of their group had been injured on the face. All he could say was that the sherpa had sustained a cut on the head, so Mok obliged with some dressings. The sherpa disappeared over the horizon quickly.

Then the weather report came in. It said that the winds over the summit for the next few days would remain favourable for a summit attempt with low wind speeds. The cyclone sighted earlier was now moving slowly to the north. However, it was also veering in a slightly more easterly direction. We would receive a dusting of snow although the winds would be pretty much dissipated by the time it reached the Himalayas. We all sighed in relief.

But by 2.30 pm, it was clear that the situation with the sherpa was more serious than was earlier reported. A disjointed radio call from the face indicated that the sherpa had been hit by either a rock or an ice boulder and was suffering from a suspected broken femur. He was incapacitated near C3 and in great pain. Rob Morrison and Robert Boice from Hoffman’s team had assisted the sherpa over a number of hours to the campsites. It was a combination of butt hauling and dragging, quite an effort at those altitudes. Sundeep Dhillon, a client from the Himalayan Kingdoms, was a doctor and he, too, went to the sherpa’s aid. I said it was no problem for them to spend the night in one of our tents and the spare oxygen could also be used if it was needed. At base camp a sled was being organised to evacuate the sherpa to BC. Our team radioed in at about 2 pm saying all was well and they would be resting up for the summit bid. They were ecstatic when I broke the good news to them about the weather. The gamble looked like it would pay off.

Mok and I were in no condition to head up to C3. There was also a great deal of frustration at C2 and BC. C2 was largely deserted except for Hoffman’s sherpas and there was not a soul at the tents of Himalayan Kingdoms. We began rummaging through their site for the special splints needed for the sherpa. After searching several tents, we found them. Most of the commercial team’s radios had been fried when connected to a faulty electrical appliance so the group was hamstrung in terms of communications. The deputy guide, Jim Williams, had raced up to C3 to assist and was not at C2 either. Apa Sherpa, the eight-time summitter, refused to help further. It was understandable. He and his sherpas were saving their energy for their push up to the Col with Hoffman’s team. Hoffman was gambling that he could summit with his team on May 20.

At about 4 pm, the clouds had come in and most of the Cwm [Welsh term for a valley] below C2 was a mass of dirty, yellow clouds. At Whittaker’s camp, Mok and I found Tom Whittaker lying on his back. He had just come up, hoping to beat the cyclone. But he was late. He was a full day behind Hoffman and two days behind the main body of climbers. He looked exhausted and his voice was raspy. There was also a watery cough. He mentioned how he was going to rest a little and then climb directly to South Col from around 3 am the following morning. He would then be able to attempt the summit on May 20. Mok and I exchanged glances. Later I shared my views with Mok.

“That guy’s going to kill himself if he tries that,” I said, unimpressed with Tom’s health and his ambitious climbing schedule.

The next morning was a bright day, and the usual C2 chill dissipated with the sun. After breakfast all three of us waited impatiently as the climbers progressed. Radio calls to Bruce the Emir reported nothing new. The last call from Swee at about 6 am reported that they had passed the Balcony and were en route to the South Summit. He sounded lucid and strong. There were few calls from the others and I hoped that they were well and had tuned in to our calls.

The plan would be for our climbers to drop off a half-used bottle of Poisk [oxygen] on the Balcony. They would make a switch to the black LSE and breathe on that until the South Summit. I knew they had done this already. Swee reported that there was quite a bit of snow and the route was packed with the 40-plus climbers and sherpas. A slight breeze had picked up at C2 but the weather up high still looked pretty clear. Despite the loss of our own summit chances, we are all pretty excited at C2 and hoping for a big success.

At about 9.15 am, we heard Swee’s unmistakable voice. They had reached the South Summit. Mok, Leong [Chee Mun] and I let out a big cheer. It meant that they were well inside the turnaround time of noon and would bag the summit over the next hour. From the South Summit, the fresh bottle of Poisk that had been carried by their sherpa would be used. A higher flow-rate of 3-4 litres could be enjoyed for the hour long section negotiating the last problem, the Hillary Step. On returning to the South Summit after summitting, the LSE bottle would be retrieved (it would still have a few hours of oxygen left in it) by the climber and the descent to the Col would continue. The half-empty bottle left there earlier in the morning on the Balcony would provide enough oxygen until they reached the tents at South Col. And they had plenty in reserve and the oxygen sequencing seemed to be going nicely.

Swee came on the radio again.

“We have a problem. There doesn’t seem to be any rope left,” he said.

Too pleased with the imminent success to absorb what he said, I replied, suggesting that they wait for it to be fixed. It was, after all, just a short section to the Hillary Step; probably not needing more than a hundred metres of fixed line or so.

“You don’t understand,” he said calmly but firmly. “The situation is more serious than you think. There is just no more rope left.”

At about 9.30 am, Swee radioed again, saying that they were turning back. The disappointment cut us to the bone. I radioed the team and asked for positional updates as they descended. Above, a small cloud had descended over the summit area and a steady breeze blew at C2. The three of us at C2 just kept shaking our heads and speculating as to why everybody had turned around. What had gone wrong with the fixed rope?

“Four years of hard work – I can’t believe it!” I said.

If there was a time profanities were in order, this was it. The weather was reasonable and the team was fit. And they were only 100 vertical metres away from the summit. The long straggling crowd of climbers picked their way slowly down the summit ridge. I kept tuning into the other channels to check if more information could be gleaned about the situation. Then in the late morning, I heard Mick’s [Crosthwaite from Henry Todd’s team] voice on the radio. Since everyone had turned around, I assumed that Henry’s team, which included the British army lads, and Alan Silva were also descending to South Col.

“Henry, this is Mick. We’ve found Alan. He’s in a bad way. He’s out of oxygen. Can we use some oxygen around here?”

Henry’s calm voice came over the airwaves. But this time, there was a strained edge to the plummy accent.

“Whatever you do, do not use oxygen belonging to other teams,” he said.

At that point, I broke into the conversation. I offered a partly used bottle from our Balcony cache if Mick and his team could find it. As our team had not pushed for the summit, they would not need the half-empties that had been left there earlier in the morning. Alan seemed to be in a deadly situation, half-comatose on the summit ridge. The situation resolved itself as Henry’s sherpas arrived on the scene and more oxygen was found for Alan.

I received one brief radio call from Roz at about noon but little was heard from the others until 2.30 pm when everyone had descended safely.

Six days later, on 25 May 1998, Edwin Siew and Khoo Swee Chiow, accompanied by four Nepalese sherpas, successfully summited Mount Everest. It was the team’s second attempt. The Singapore Mount Everest team was conferred the Singapore Youth Award (Sports and Adventure) by the National Youth Council in July 1998, as their “exemplary dedication, discipline and determination to be the first Singapore team to conquer Mount Everest serve[d] as an inspiration to all Singaporeans”.5 Mountain to Climb is available for reference at the Lee Kong Chian Reference Library and for loan at selected branch libraries (call nos. RSING 796.522092 LIM and SING 796.522092 LIM.)

Singapore

David Lim Yew Lee, leader/climber (multimedia executive)

Justin Lean Jin Kiat, 25, climber/communications (student)

Khoo Swee Chiow, 33, climber (system analyst)

Leong Chee Mun, 33, climber (teacher)

Edwin Siew Cheok Wai, 28, climber (outdoor activities instructor)

Mok Ying Jang, 30, climber (physician)

Robert Goh Ee Kiat, 33, (defence engineer)

Mohd Rozani Maarof, 30, (service technician)

Shani Tan Siam Wei, 39, team doctor (anaesthetist)

Johann Annuar, 23, communications officer (student)

Bruce Mackenzie Niven, 63, base camp manager (consultant)

Nepal

Man Bahadur Tamang (sirdar)

Climbing sherpas

Kunga Sherpa (deputy sirdar)

Dorje Phulilie

Pasang Gambu

Kami Rita

Nawang Phurba

Phurba Sherpa

Fura Dorje

Dawa Tshering

Lhakpa Tshering

Dawa Gyalzen

Lila Bahadur Tamang

Other base camp staff

Urke Tamang

Sonam Lama

Pralhad Pokharel (liaison officer)

Thal Bahadur Adhikari (Badri)

Birbahadur Tamang

Gun Bahadur Tamang

Yula Tshering

David Lim is a veteran of more than 70 alpine ascents and expeditions, having climbed the French, Swiss and New Zealand alps. His company, Everest Motivation Team, provides leadership and change management consultancy services. David is also a motivational speaker and writer. He read law at Magdalene College, University of Cambridge, and worked in the media industry for more than a decade.

David Lim is a veteran of more than 70 alpine ascents and expeditions, having climbed the French, Swiss and New Zealand alps. His company, Everest Motivation Team, provides leadership and change management consultancy services. David is also a motivational speaker and writer. He read law at Magdalene College, University of Cambridge, and worked in the media industry for more than a decade. Notes

-

Mount Everest is known as Chomolungma by the Tibetans and Sagarmatha by the Nepalese, which mean “Goddess Mother of the World” and “Goddess of the Sky” respectively. ↩

-

Freddie Wilkinson, “Want to climb Mount Everest? Here’s What You Need to Know,” National Geographic, 29 October 2022, https://www.nationalgeographic.com/adventure/article/climbing-mount-everest-1 . ↩

-

Yong Li Xuan, “Search and Rescue Team Unable to Find Missing Singaporean Everest Climber, Says Wife,” Straits Times, 28 May 2023, https://www.straitstimes.com/singapore/search-and-rescue-team-unable-to-find-missing-singaporean-everest-climber-climber-s-wife. ↩

-

David Lim, Mountain to Climb: The Quest for Everest and Beyond (Singapore: Epigram Books, 1999). (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSING 796.522092 LIM); David Lim, Mountain to Climb: The Quest for Everest and Beyond (Singapore: South Col Adventures, 2006). (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSING 796.522092 LIM) ↩

-

Daisy Ho, “Everest Team Bags Award,” Straits Times, 30 June 1998, 23; “Who Reached the Summit First?,” Straits Times, 28 May 1998, 31. (From NewspaperSG) ↩