American Troops. Singapore Bands. The Vietnam War

Lured by the prospects of money and adventure, local performers braved the dangers of the Vietnam War to provide entertainment to American troops.

By Boon Lai

The Vietnam War, which ended in 1975, is a distant memory to most people in Singapore who lived through the period. For many, it was an event that largely did not touch their lives personally. While fierce fighting was taking place in the region, to many in Singapore at the time, the main face of the war was drunk soldiers on rest and recreation leave.

However, for a small group of Singaporeans, the war in Vietnam was highly personal. Some of them were photographers and cameramen who worked for news organisations covering the war. Embedded with American troops who were doing the fighting in South Vietnam, they were exposed to the same dangers as the soldiers. And like the soldiers, some of them lost their lives.

Apart from daring local journalists, there was another group of Singaporeans who were personally affected: local singers and bands who had gigs to entertain American troops in Vietnam. Young, seeking adventure, and looking for a chance to earn some cash, these musicians signed up without knowing what they were in for.

Once there, they were plunged into a situation unlike anything they had experienced before. Apart from keeping their instruments tuned, they had to learn to fire weapons (they were given a crash course). Getting to each gig did not involve merely a tour bus; sometimes, they were flown there in helicopters that would come under fire.

This is what life in a war zone was like, as told by three musicians who experienced it: Veronica Young, Harris Hamzah and Steve Bala Siren.

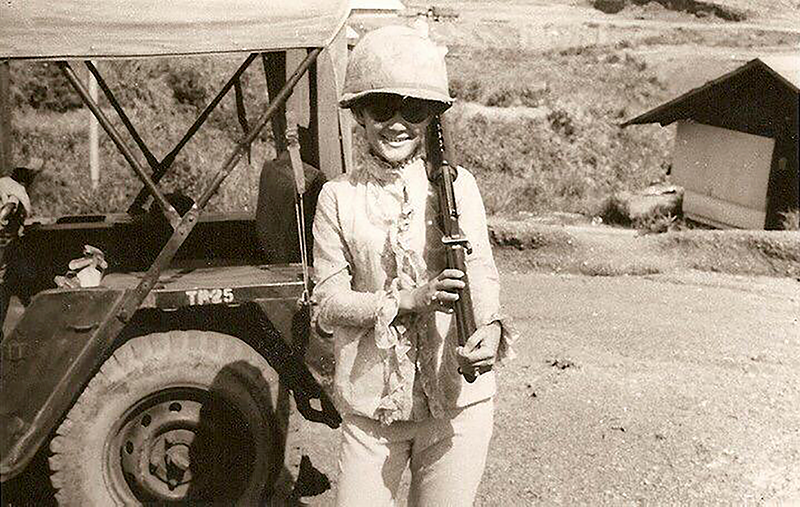

Veronica Young

Veronica Young got her break in 1964 at the age of 16 when she met prominent local musician Siva Choy. She was a versatile singer, performing with many bands (such as the Silver Strings and The Quests) and singing at local clubs, British military bases and in shows at Capitol Theatre or Odeon Theatre Katong. She was the winner of the “Singapore’s Millie Small” competition (Mille Small was a Jamaican singer best known for the 1964 hit “My Boy Lollipop”), which opened doors to other opportunities including recording deals under the Philips label. By the time she was 20, Veronica was performing extensively in Singapore, Malaysia and Borneo.

One day, she was approached by an agent about going to South Vietnam to play with local Malay band, the Impian Bateks. She jumped at the opportunity. “I was only concerned with singing, didn’t care or know much about what was happening around the world,” she said.

Veronica flew to Saigon (Ho Chi Minh City today) with the Impian Bateks in 1969.1 Landing at Tan Son Nhat Airport, the grim reality hit her. She saw “[a] country that looked sad. War-torn. Soldiers everywhere… The situation was… like what we see in the movies”.

A few days later, Veronica, the Impian Bateks, and two dancing girls (on occasion a Korean stripper would join them) started their tour. They went to American bases around then South Vietnam, such as Phu Bai, Phu Loi, Quang Tri, Chu Lai, Cam Ranh Bay, Da Nang. They travelled by road or air via army trucks, C130 planes, CH-47 Chinooks and Huey helicopters, to and from the 10 major bases, to over 100 towns and military outposts throughout South Vietnam.

Veronica and the Impian Bateks were assigned a Filipino manager by their Korean agent. They played hundreds of gigs within the span of a few months. Their schedules were unpredictable and gruelling. “Sometimes, we had to leave in the morning and travel just to make a show at night,” she recalled. “Sometimes, it took us one to two days to get to the next destination.” She later discovered while they were receiving US$400 per month, the agents were getting US$400 per show.

They performed indoors in clubs and mess halls and outdoors on makeshift stages. Conditions ranged from basic to downright poor. Sanitation was a major challenge. Female entertainers also attracted a lot of unwanted attention – shows often got wild, even with the military police present. Some soldiers would try to take advantage of the girls, even trying to sneak into their quarters. Friendly exchanges sometimes led to demands for sex or worse.

Veronica recounted an incident at the Chu Lai barracks. It was dark and quiet, and she was alone at the cooking stove at the end of the barracks. She was boiling a pot of water, cutting chillies. She did not hear anything, but someone suddenly pounced on her and wrapped his arms around her. She instinctively thrust the knife in her hand backwards into the gut of her unseen assailant. There was heavy thud. She looked down and saw a GI groaning, writhing in pain, bloodied. Startled but relieved, she said, “Sorry… you got the wrong one.”

Yet, Veronica remembers most of the troops as “nice and polite”. She said, “They were waiting just to touch you. They didn’t mean any harm. It was so sad. They were there – to live or die – they didn’t know… having been sent over.”

Once, onboard a C130 Hercules airplane en route to their next gig, Veronica overheard the pilots asking about the girls. She asked the crew for his headset and joined the conversation. “Which one are you?” the pilot asked. She replied coyly, “The small pretty one that sings. Now, which one do you want to know about?” Veronica was invited into the cockpit. “Would you like to fly?” the pilot asked. She jumped at the chance and squeezed into the co-pilot’s seat. She gripped the yoke tightly, sending the plane into a sudden dive, momentarily suspending everyone mid-air. Fortunately, the pilot quickly regained control and steadied the plane.

On another occasion, this time in a helicopter, Veronica asked to sit next to the door gunner. Flying between Cam Ranh Bay and Da Nang, she asked if she could fire the mounted heavy M60 machine gun: “One shot?” She had to wait until they reached a clearing before the gunner gave her the go-ahead. He placed his hands on her and said, “But I gotta hold you.” She responded that she didn’t care what he did. “You can hold me or kiss me. Just let me shoot!” She pulled the trigger and bullets sprayed out in rapid fiery bursts, tearing through the air. The powerful recoil of the machine gun threw her violently back and she realised why the gunner had insisted on holding on to her.

But the realities and atrocities of war were unavoidable. Escorted by soldiers, Veronica remembers seeing signs of brutal confrontation as they passed underground tunnels, the sites of bloody fighting. “I’ll never forget it… Even now, talking about it, I have it in my vision. A dead body, covered in maggots.”

Veronica returned home after her first tour and embarked on her second a little more than a year later in 1971. “Things [were] much [more] peaceful there than before. But the entertainment scene had also become poorer.”2 When asked if she would go for the third time, she replied that it was no longer worth it since the United States (US) were withdrawing its troops.

Harris Hamzah

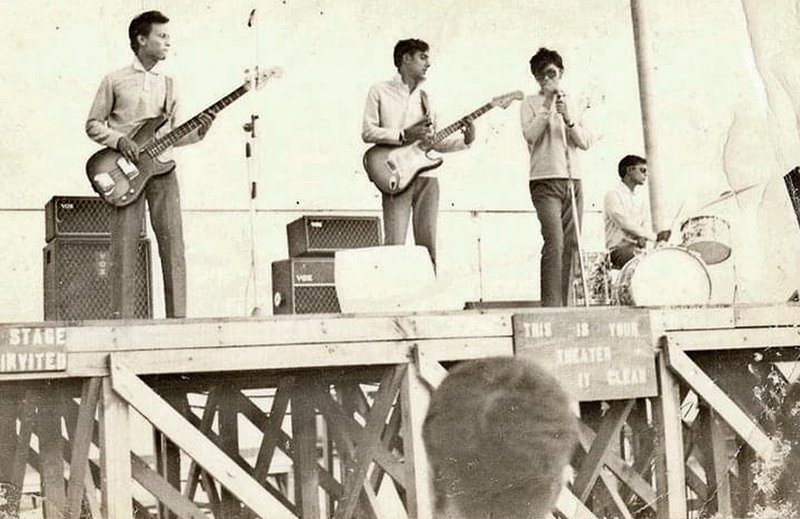

In July 1969, the Berita Harian newspaper announced that Singapore-Malay band Impian Bateks would embark on their first South Vietnam tour.3 The Impian Bateks comprised vocalist and manager Rudin Al-Haj, keyboardist Ismail Ahmad, drummer Jantan Majid, lead guitarist Harris Hamzah and bassist Suffian. When asked about their decision to go to Vietnam despite the dangers, Harris said, “Our families were worried, but the money was really too good.”

The band stayed in their agent’s halfway house in Cho Lon, Saigon, and within days, it became clear that they were in a danger zone. Bursts of gunfire rang out day and night. News of bands being blown up mid-performance rattled young Harris: “Whenever I saw a box or a can left unattended, I’d stay away. We didn’t feel safe.”

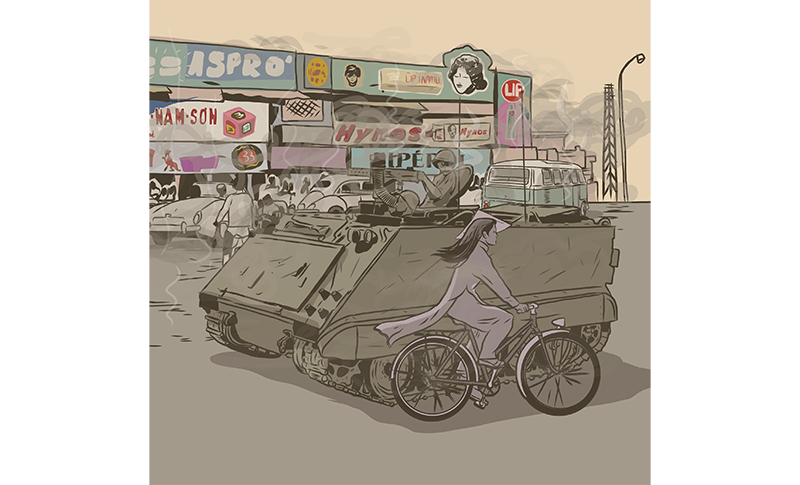

Once considered the Pearl of the Orient, Saigon had developed the reputation of a Sin City. It was already overcrowded but more and more people kept flooding in, fleeing their battle-ravaged villages for the perceived safety of the city. The enormous inflow of US dollars drove prices up, and grossly inflated American goods were peddled alongside drugs, booze and sex. The Vietcong (a communist guerilla force supported by the North Vietnamese army to fight in the South) were everywhere, effectively putting Saigon under siege.

“The [US soldiers] would talk to us,” said Harris. “Some of them would show us photographs of friends who were killed stepping on boobytraps and mines. Like them, we were also given [dog] tags to wear in case anything were to happen to us… Sometimes, when we boarded the transports, there would be someone there praying, as if we might not make it.”

Recounting chopper rides to remote outposts, Harris said that he sometimes had to sit on the sides of the choppers. “And the GIs, maybe drunk or high on drugs, would just shoot at anything they [saw].” Drug use was common among the GIs. “Maybe they were given drugs so that they [could] keep on fighting. It was everywhere. Like it was free.”

Harris described playing in Vietnam as “very challenging”. During the monsoon season, it would get very wet and muddy. Behind trucks, on shaky stages, under tarpaulin canvases or parachutes – anything that could provide cover from the intense sun or rain – entertainers played on even with gunfights taking place nearby. They had to improvise. “Often we didn’t get to wash properly,” recalled Harris. “We wore the same clothes for days. They were stinking of dried sweat. We couldn’t always get clean water. I even bathed once using beer!”

Steve Bala Siren

Steve Bala Siren was the founder and lead guitarist of the band Esquires. A Korean agent had offered the band US$2,000 per week for a six-month stint in Vietnam, along with half a million dollars of insurance money for their families in the event of death. The band, comprising Steve Bala Siren, Gilbert Louis (guitar), Charlie Sundaram (drums), Denys Logan (vocals) and Raymond Lazaroo (bass), agreed to go even though they had no idea what to expect.

The band arrived in May 1969 and Steve remembers the grim welcome of 50-millimetre gun turrets mounted on sandbags and signs of fresh skirmishes on the drive from the airport to Saigon. “There were gun turrets along the route, sandbags stacked,” he recalled. “Buildings were half-standing. The whole place was quiet and grayish.”

For their first show, the Esquires flew to the US base in Cam Ranh Bay in a C130 Hercules. Upon arrival, Steve was assigned an M16 rifle and a .45 side revolver, and given a crash course on how to handle the weapons, change magazines and shoot.

The band travelled with three strippers and a Filipino roadie, often squeezing into a single Huey helicopter to get to their gigs. “Our instruments were strapped in the middle, the girls were in the middle on the seats, and [the boys] were on the sides with our legs dangling out in the open,” he said. “No doors! We had two gunners on the left and right, with two 50 mm guns on the sides. Occasionally, they fired. And we [got] fired at.” Zipping over treetops across battle-ravaged vistas, the GIs played songs on mounted speakers, blaring out the likes of Credence Clearwater Revival’s “Run Through the Jungle” and The Animals’ “We Gotta Get Out of This Place”.

The chopper would land at landing zones near the forest. Out in the clearing, four army tanks would have been lined up, with a wooden platform on top as a stage. He said, “[At first] there was nobody, just us.” They set up their instruments and a flimsy curtain so the girls could change backstage. When they were ready, the band strummed the final tune-ups.

Within 15 to 20 minutes, GIs appeared out of nowhere in camouflage – twigs and leaves on their helmets. Thousands of them, shouting the titles of Jimmi Hendrix songs like “Purple Haze” and “Fire”. The girls turned up the heat with their routine. At the last minute, they stripped completely, sending the GIs into a frenzy and showering the stage with money. “At the end of the show, we collected the money in a box. US$300–400 dollars per show.”

Danger was everywhere. During a show at a base in Chu Lai, bassist Raymond Lazaroo was playing just next to Steve and they both heard a sharp zipping sound cutting through between them. They looked at each other and turned back. In the wall behind them was a fresh bullet hole.

Being ensconced in an American base did not mean that the performers were safer. Early one morning, Vietcong soldiers were spotted creeping around the barracks where the Esquires were staying. Sirens went off and the band was ordered to stay by their bunk beds. A fierce gunfight ensued. After the lockdown was lifted, they went to the mess hall for breakfast and saw the bloodied bodies of six Vietcong laid out on the floor.

Steve had heard of other incidents too. “[The Vietcong] wiped out a whole Filipino band… they came into where [the band] was staying and took five boys and two girls,” he recalled. “All seven of them were shot dead. To the Vietcong, you are entertaining the GIs, so you’re just like the GIs. You are my enemy.”

Their worst experience was on 6 September 1969, when the band was in Da Nang at their agent’s villa called the Stone Elephant Villa. They had broken curfew and were outside when the shelling began after midnight. The band made a panicked run for their villa. Nearly 200 rockets pummelled Da Nang and nearby installations that night.4

“When [the rockets] hit the ground, it was like millions of diamonds thrown up, right in front of us!” Reaching the villa, they hid under their metal beds. The onslaught persisted until dawn. In the end, 17 Vietnamese and three Americans were killed, with 23 Vietnamese and 120 Americans wounded.5

By then, the Esquires had decided that they would not tempt fate further. They flew home in November 1969.

Living to Tell

Now in their 70s, Veronica, Harris and Steve are still living out their passion for music. Steve resides in Sweden and performs on cruise liners plying the Atlantic. Veronica lives an active life in France and performed at the Esplanade – Theatres on the Bay in early 2023. Harris still lives in Singapore and performs whenever he has the opportunity. The trio performed in extraordinary circumstances and lived to tell the tale. They, and other unsung entertainers, had given soldiers cheer, comfort, escape and some connection to their home and families faraway.

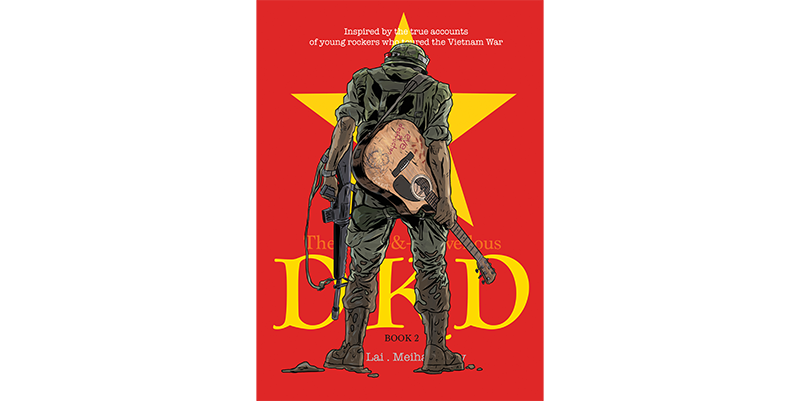

Boon Lai is a content creator, author, illustrator and filmmaker based in Singapore. Inspired by the true accounts of the rockers who toured the Vietnam War, he created the three-book graphic novel series, The Once & Marvellous DKD (dkdgraphicnovel.com).

Boon Lai is a content creator, author, illustrator and filmmaker based in Singapore. Inspired by the true accounts of the rockers who toured the Vietnam War, he created the three-book graphic novel series, The Once & Marvellous DKD (dkdgraphicnovel.com). Notes

-

“‘Impian Bateks’ Akan Berhijrah Ka-Saigon,” Berita Harian, 13 July 1969, 12. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Vietnam Through As ‘Breaking-Ground’ Says Veronica,” Straits Times, 9 April 1971, 10. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Penyani Pulang Rindukan Keluarga,” Berita Harian, 7 November 1969, 2. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Da Nang Under Heavy Rocketing,” Desert Sun 43, no. 29, 6 September 1969, https://cdnc.ucr.edu/?a=d&d=DS19690906.2.3&e=——-en–20–1–txt-txIN——–1. ↩

-

“Apa Kata Gadis Manis Ini Yg Baru Pulang Dari Saigon,” Berita Harian, 9 April 1971, 8. (From NewspaperSG) ↩