Gloved Gods: Battling Key, Yeo Choon Song and the Roaring 20s of Singapore Boxing

In the aftermath of World War I, the “noble art” became wildly popular in Singapore thanks to two Straits Chinese who took on all-comers, including each other.

By Abhishek Mehrotra

On 15 July 1896, an advertisement in the Straits Times Maritime Journal and General News invited readers in Singapore to witness what it promised would be a marvellous exhibition of boxing by “The Wonder of the Age – ‘Peter Jackson’”. 1

This would normally not have caught the attention of this 21st-century researcher had it not been for a singular fact: Peter Jackson was a boxing kangaroo. It had arrived in Singapore from Fremantle, Western Australia, on the steamship Sultan in June.2

It would take another quarter of a century before human beings replaced sparring marsupials in newspaper ads and the public imagination.

Beginnings of Professional Boxing

When World War I ended in 1919, Singapore had a restless population of migrant Chinese labourers thirsting for some cheap entertainment. Gradually, the island started to gain popularity as a stopover for travelling exhibitions and circuses. According to at least one source, it was “Colonel” Frank Fillis of the famed Fillis circus who started the trend in 1921 with a hastily organised “flyweight championship of Malaya” after ticket sales for the circus started to flag. The fight between two locals, Fred de Souza (also known as the Red Warren) and Kong Ah Yong, raked in over $4,000.3

In another source, it was the brothers Edwin and Stewart Tait who first brought boxing to these shores.4

The Taits, Americans from Tacoma in Washington state, were entertainment moguls with business interests on either side of the Pacific. Their main base of operations in Southeast Asia was the Philippines – then a US colony – where they owned five carnivals and assisted in the running of the Manila racecourse.5

More than anything though, the brothers loved boxing.

In 1920, the Taits brought a travelling circus to Singapore, and in an apparently spur-of-the-moment decision, constructed a makeshift boxing ring to host exhibition bouts after the evening’s main entertainments were done.6 The first few fights were between Filippino circus workers. As interest grew and larger crowds started gathering, the brothers invited daring onlookers to fight them.7

This humble beginning was the taproot from which sprang the heady, golden years of boxing in Singapore.

The sport held a peculiar fascination for the locals. Unlike cricket, tennis or swimming – which were mostly confined to exclusive upper-class clubs for the affluent – boxing belonged “to the greater mayhem and disorder of the streets”.8

It also lent itself to betting. In a remarkably short span of time, boxing bouts took their place alongside cards and dominoes as a favoured betting avenue. Boxers became cult figures.

Pulling No Punches

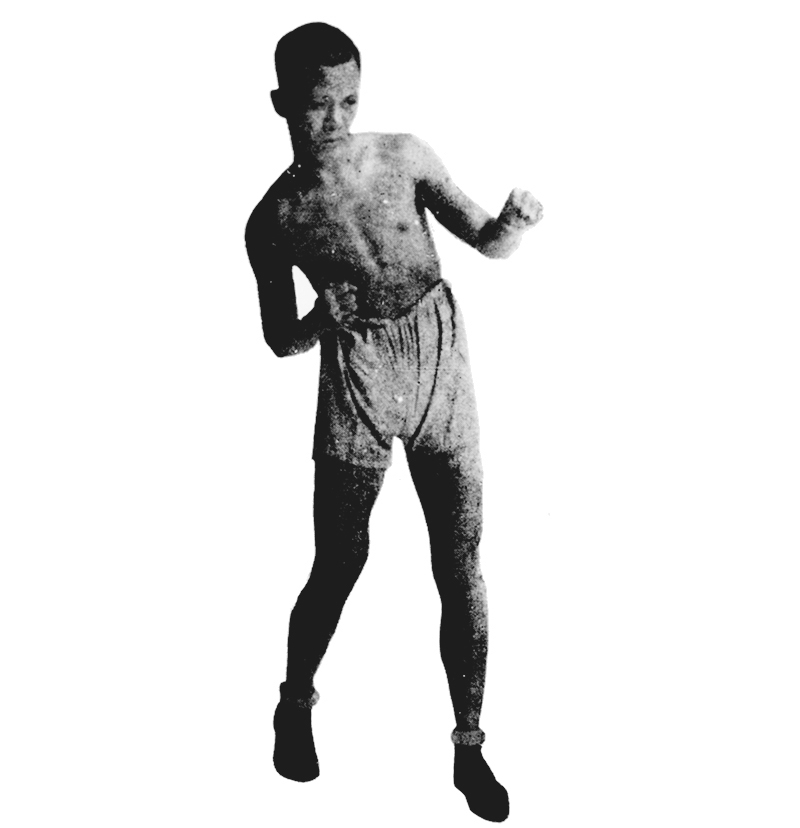

The first local hero was an unlikely one – a Straits Chinese named Tan Teng Kee. Born in 1898 to a respected family whose head was a sinseh (traditional Chinese physician), Tan had attended the venerable St Joseph’s Institution – a natural stepping stone to a “respectable” white-collar profession.9 To the family’s shock though, Tan decided to don boxing gloves. His nom de guerre: Battling Key.

The circumstances leading up to Battling Key’s decision are lost to history. What is known is that by August 1921, only a year after boxing had come to Singapore, he was facing off against a certain C. Oehlers in the final of the colony’s amateur lightweight championship at the packed Palladium Theatre (site of the Orchard Gateway today).10

The Straits Times was on hand to record the events of that fine August evening. “About halfway through the second [round], Oehlers rushed, wide open and Teng Kee, quick to seize the opportunity, met him with a right upper cut. It was a peach of a punch, landing well on the point and with force behind it, and Oehlers went down and out. There are distinct possibilities in Teng Kee. A lad who learns how to place a punch like that practically by instinct might go far with proper handling.”11 Battling Key had won the match in the only knockout of the evening.

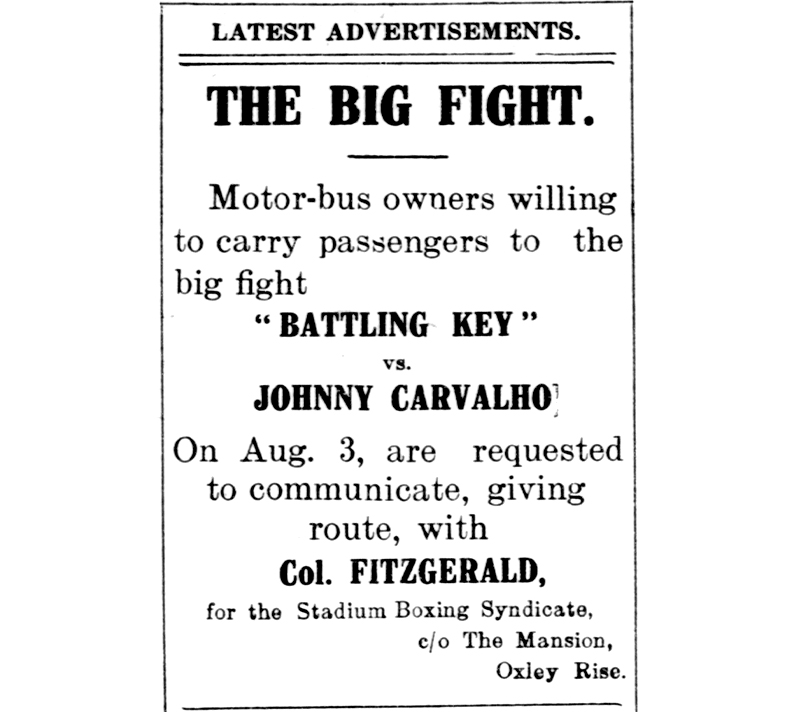

On the back of this triumph came a trio of fights in 1922 that showed just how far Battling Key had come. The first was against Johnny Carvalho, a fierce hitter from across the strait who was dubbed the “Johore Tiger” for his ferocity. In the first go, in April that year, Singapore’s star man outpointed Carvalho over six rounds. Carvalho evened the score a mere two months later, battling to a win in 10 rounds in front of a mesmerised crowd at the Victoria Theatre. On 3 August, the duo met one final time in front of a capacity crowd almost sick with anticipation.12

The duel was over in 105 seconds.

“Teng Kee left his corner with a rush when the gong sounded, and Carvalho was evidently taken by surprise at the swiftness of his opponent’s tactics… [Teng Kee] was out to win without giving Carvalho a chance. He scored almost immediately, before the Johore man had much time to realise what was happening, with a right to the face… landed a right swing well to the side of the jaw. Carvalho went down and there was a roar from all parts of the building. Half way through the count he rose upon one knee, and seemed to make an effort to rise. He failed to do and Teng Kee was immediately lifted to the shoulders of his seconds and chaired round the ring to the accompaniment of a perfect storm of applause.”13

Battling Key was now without doubt the best lightweight in Singapore’s young boxing history. Sensing his vast earning potential, his shrewd manager – a man called J.F. Pestana – convinced him to turn professional within months of the historic Palladium triumph.14

By 1922, Pestana and his charge could demand up to $2,000 purses (the minimum guaranteed sum for a boxer, irrespective of the outcome) for a single fight.15 It was just as well, for Singapore’s first boxing star had a reputation for spending money as fast as he earned it. Handsome, well dressed and oozing machismo – when his family and friends voiced their disapproval of his career choice, he reportedly said: “I love boxing and I am prepared to die fighting in the ring” – Key was the first boxing, and probably the first sports, megastar in Singapore.16

Crowds would often follow Key whenever he emerged on the streets and reports from the time indicate he was one of the few fighters whose popularity transcended gender. Many youths were inspired to take on the sport seriously because of him. In later years, he endeared himself even more to his followers by appearing in charity matches.17

In October 1923, two months after it was inaugurated, New World amusement park hosted its biggest event. Battling Key, by now the undisputed lightweight champion of all of Malaya, was up against Young Pelky (real name Lope Tenorio; he would later rank within the top five junior lightweights in the US), a tall, slim Filipino who “carried a punch like a mule’s kick” in a 10-round blockbuster.18

The atmosphere was electric. Ticket prices for ringside seats around the open-air arena had been hiked from the standard $5 to $10 (and even resold for $20 and more) and yet not a single one was unoccupied. Around them, a crowd of 6,000 shifted restlessly as dusk fell on the mid-October day. Powerful lamps from all four corners set the ring aglow. The local man strode out first, to a massive roar. Young Pelky, a showman himself, took his time – walking leisurely and chatting with friends in the crowd – before making his way to the ring.19

As soon as the bell went, the fight began. “Everyone who saw it will admit that it was a good go. There was no science about it,” reported the Straits Times. “Each man went for all he was worth, swung wildly and at times missed by feet; still it was the kind of thing which kept the crowd interested.”20

The first few rounds were evenly matched before Pelky’s cannons started finding their mark. A punch to the throat towards the end of the sixth round sent Battling Key staggering to his corner. In the seventh, Pelky got his man thrice; in each instance, the blow slammed his opponent to the ground. Twice, Key got up. On the third he was saved by the bell indicating the round was over.21

Lesser men may have thrown in the towel, but the battered Key returned for the eighth round. It took four more thunderous blows from Pelky, including one square on the jaw, before the local hero hit the floor and stayed there. The Filipino had won but the Straits Times noted that “the courage with which Key stuck it to the end made him the popular hero”.22 Later reports claimed that the many Chinese women who had come to witness their idol left the arena weeping.23

Promoting Boxing

Soon, a semblance of structure began to take shape around the sport. Up-and-coming fighters would be pitted against each other on weeknight matches, which were presumably cheaper than the seats on Friday or Saturday nights. For boxing managers, always on the lookout for new talent, these were fantastic scouting opportunities. The most promising fighters were first upgraded to weekend support acts – engaging in preliminary fights to warm the crowd up. Those who did well would eventually become the main acts themselves, the ones who brought the crowd traipsing through the doors of Happy Valley (an older open-air arena on Anson Road) or New World.

Even though the boxers brought in the money, it was the managers and promoters who wielded the power. Vitally, the promoters – businessmen with a keen eye for profit – had to be willing to put up the money that would pay for the boxers’ purse (and travel plus accommodation if one or both were coming in from overseas), newspaper advertisements and printed flyers to drum up hype, and entertainment tax if applicable. Chairs for spectators had to be rented, and referees, poster boys and handbill distributers had to be paid.24

These were just the official expenses.

To ensure favourable and wide-ranging press coverage, “donations” were sometimes made to the sports writers’ club or a similar organisation.

After the various fees and commissions had been decided, and suitable palms greased, the promoter(s) were reliant solely on ticket sales to turn over a profit. Despite these challenges, some individuals – businessmen presumably – were bullish enough to form boxing syndicates to cash in on the sport’s burgeoning popularity. For instance, an entity called the Stadium Boxing Syndicate organised and promoted the Key versus Carvalho fight in 1922.25 Another one, called the Straits Boxing Syndicate, bought exclusive rights to hold all fights at the Happy Valley arena.26

Little is known about the group apart from the fact that it was formed sometime in late 1923 or early 1924, when Battling Key was at the height of his powers. It became the dominant boxing promoter in Singapore – organising numerous bouts pitting the premier local boxer against some of the biggest names in the region – mostly Filipinos. The key, pun intended, was having a home-grown hero who could put up a good show. The result was secondary.

And so they came to fight the Singapore boxers. Cowboy Reyes, Battling Guillermo, Young Pelky, The Johore Tiger, Kid Apache and Speedy Dado – men with big reputations and monikers that leapt out from the promotional posters plastered all over the city. Mostly, they fought in sold out arenas as the redoubtable Key drew spectators in droves.

Even as boxing flourished in the colony, a nagging doubt crept into promoters’ minds. After Battling Key, who? As one Straits Times correspondent noted in January 1927, “Boxing booms when there is a local champion, and in a place like this, it is important from the promoters’ point of view that the champion should be Chinese.”27

Battle of the Champions

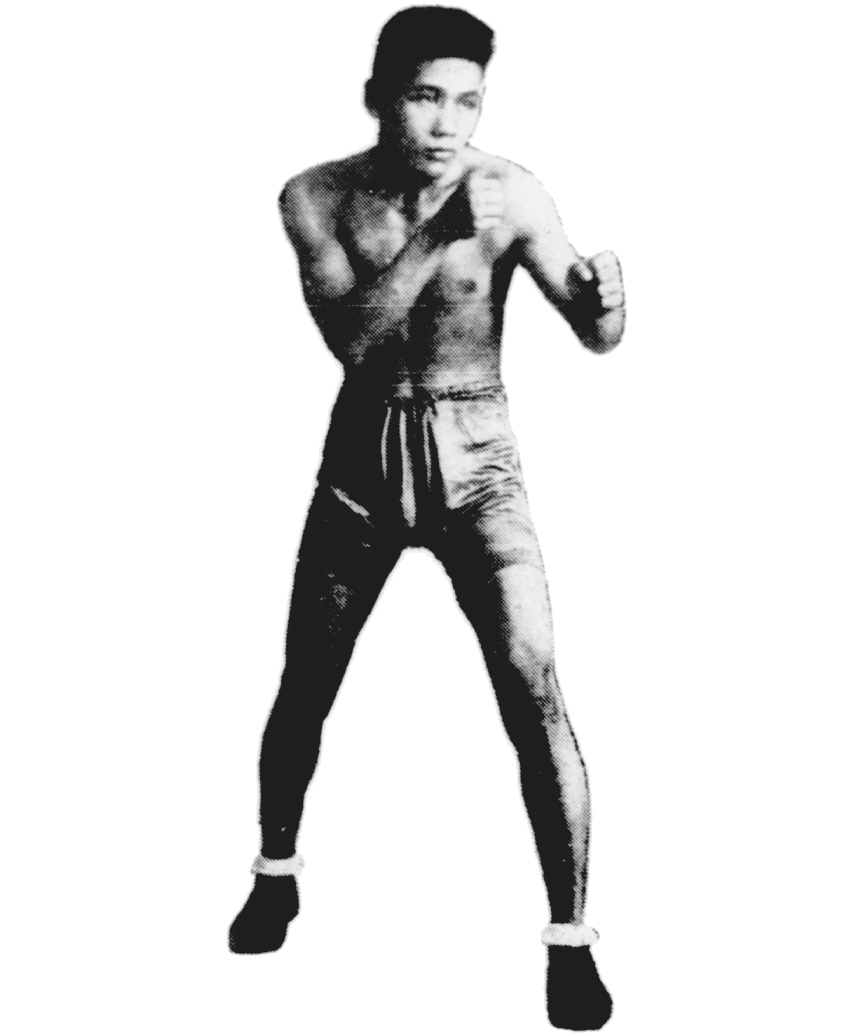

Luckily for the promoters, even as Battling Key was thrilling audiences, yet another strapping Straits Chinese fighter was biding his time. Legend has it that Yeo Choon Song (known as Y.C. Song in the press), a boxing-besotted teenager like many of his contemporaries, was in the audience for an evening of bouts at Happy Valley when he remarked to his friends: “I think I can beat most of those boxers.”28

As luck would have it, one of Yeo’s friends was acquainted with boxing manager Tan Ngee Yong and took Yeo to meet Tan at River Valley Road the very next morning. Within a year, Tan and his burly Straits Chinese protege had become a crack team. In 1924, when he was all of 18, Yeo went on a tear – winning 20 fights in a row and becoming known for his fearlessness backed with quick, accurate punches with the right-hand, a walloping left and a solid defence.29

Over the next few years, Yeo became a regular fixture on the boxing circuit, moving from four rounds to eight and beyond, from relatively low-key weekdays to glittering weekends. However, Yeo really shot to fame when he knocked out Filippino legend, the veteran Cowboy Reyes, in January 1927 with a left hook to the body that almost sent Reyes “back to the Philippines”.30

It was a blow that resounded across the colony, loud enough for the Straits Sporting Syndicate (it is not known if the Straits Boxing Syndicate had changed its name or if this was a separate entity) to sit up and take notice. If they could bring Battling Key and Yeo into the ring, a hefty paycheck was all but guaranteed.

Key had, of course, spent the previous years taking on all-comers in Singapore and overseas. In 1925, he had wrested the Malayan lightweight title back by beating the Kuala Lumpur champion Vincent Pereira, before winning audiences the region over with his indomitable performances in Manila, Hong Kong, Saigon and Bangkok.31

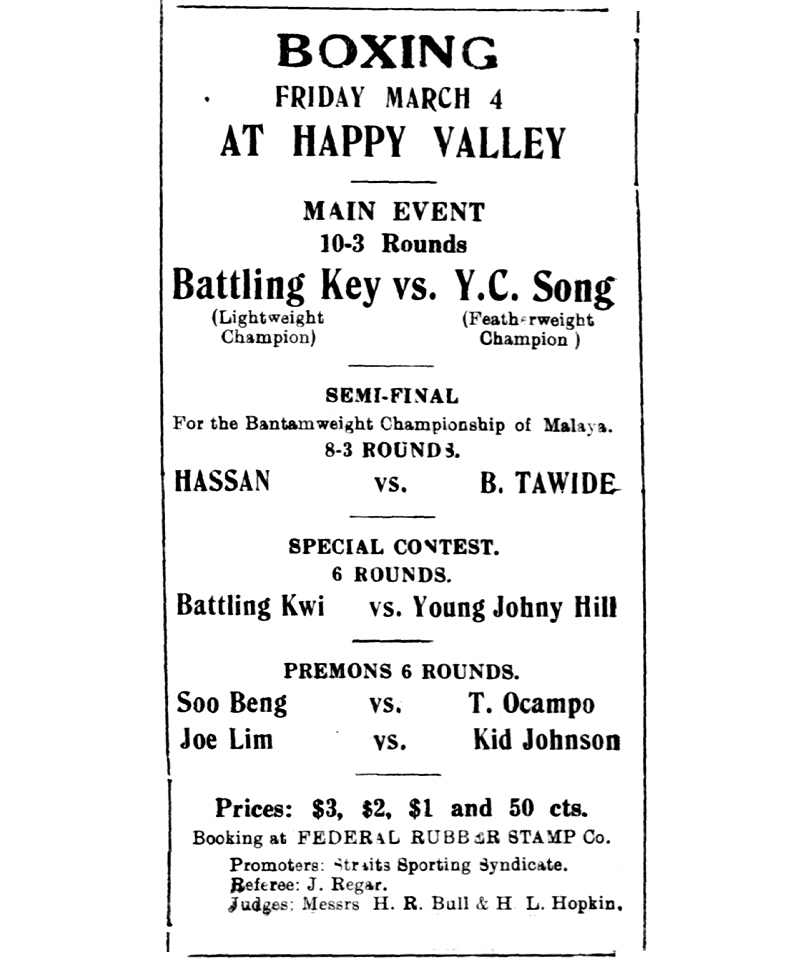

The promoters moved quickly. Battling Key would fight Yeo on 4 March 1927 at the Happy Valley arena for the featherweight championship title of Malaya. A better script could not have been written. For the first time in Singapore’s boxing history, two local Chinese were providing the main event. One a pioneering legend; the other hammering on the door to greatness. Tickets were set at $3, $2, $1 and 50 cents, with the Malaya Tribune predicting a “crush at the box office”.32

The night’s festivities got off to a promising start when Singapore’s Young Hassan beat Filipino Bagani Tawide in one of the preliminary fights to become Malaya’s bantamweight champion. Soon, Battling Key and Yeo emerged – both in supremely fit condition – for 10 rounds of three minutes each.33

Key went on the attack from the beginning, but Yeo nimbly side-stepped most of the jabs. Things got more frenetic in the second, with both men landing a few exploratory punches without delivering the knockout blow. By the third round, the crowd was in full voice – Yeo’s supporters especially making their presence felt by keeping up a continuous din. Inside the ring too, the drama escalated. After a punch by Key found its mark, Yeo complained to the referee about his opponent’s gloves. “[H]e probably thought the Key had a horse shoe stuffed in them,” wrote a local wit the next day. The official, though, allowed the fight to continue after a brief examination of the mitts, and an enraged Key went after his younger opponent with renewed gusto.34

It was a mistake. Yeo was simply too quick, and Key’s exertions started to take a toll. By the fifth round Key had slowed down considerably, and the crowd, punch-drunk on the action, now roared for the 21-year-old to finish off the veteran. In the eighth round, Yeo got his chance and pummelled Key with numerous blows to the head until it seemed like all that was left was the coup de grace. Key, though, summoned his famed powers of resilience to mount a final fightback – a flurry of fists to Yeo’s face, delivered with such ferocity that one of them cut Yeo’s left eyebrow “to the bone”. Soon, the challenger was covered in blood.35 The referee was forced to award the fight to Key, even though Yeo had had the better of the exchanges.

It had been a dramatic evening, but the anti-climactic end meant there was immense desire among the public, promoters and the two boxers for a rematch.

It is a pity that no photos or ephemera exist from the second encounter between Yeo and Key held on 12 August 1927 at the same arena. Both men entered the ring sporting a plaster above the left eye – Yeo protecting his old injury, and Key a recent one sustained while training for this fight. The fight followed a similar pattern to the first. Yeo was too quick for the older man, and seemed to be running away with the encounter, especially once Key’s left eye swelled completely shut in the seventh round. In the eighth, the two butted heads with such ferocity that Yeo’s old cut tore open – but this time the referee allowed the fight to continue. By the tenth and final round, the result was foregone.36 Yeo had won hands down.

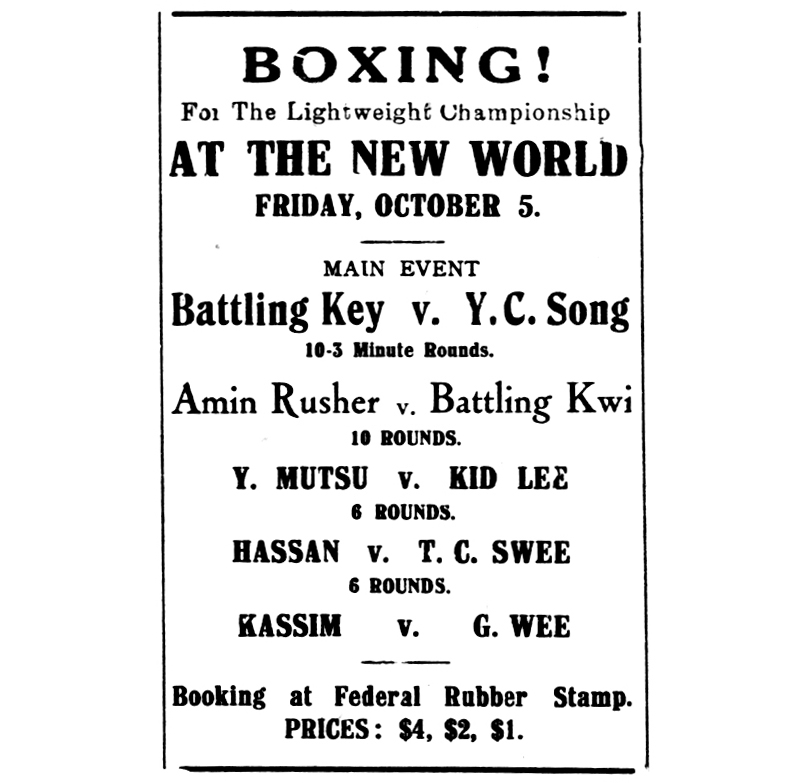

A third, deciding encounter took place 14 months later, on 5 October 1928 – this time at Singapore’s premier venue, the New World stadium. Newspapers hyped up the animosity between the two, going back to the time Yeo had complained about Key’s gloves during the duo’s first encounter the previous year.37

“Followers of boxing can rest assured of an exciting fight, for neither of the pair has any love for the other,” wrote the Malaya Tribune. “In other words, it will be a grudge fight.” Key even baited his younger opponent, saying he hoped Yeo would actually fight and “not turn the ring into a race track”.38

In truth though, Key was the underdog. He was 30 years old, and years of punishment in the ring had taken their toll. Even though Yeo was nursing an injury to the left hand sustained in a recent bout, he was the clear favourite.

“The veteran was painfully slow,” mourned a reporter with the Straits Times, “and Song easily blocked his efforts to score, while again Key showed that he has claims to the title of ‘world’s champion shock-absorber’”. “Left-hand, left-right, the punches landed on Key’s jaw, and the crowd marvelled that he can take so much and still keep going.”39

Key lasted the entire 10 rounds, hanging on in the hopes of landing a miraculous punch that would knock Yeo out cold. It never came. At the end, Singapore’s most beloved boxer was bruised, battered and beaten into submission by a formidable successor – an outcome as inevitable as it was sad.

“Those who remembered him as he once was, however, thought regretfully of the ‘Battler’ who was remarkably fast and certainly the best lightweight produced locally,” was how the Straits Times captured the evening’s mood. Yeo, having beaten Cowboy Reyes and Key in short order, was now both the featherweight and lightweight champion of Malaya.40

The Golden Age of Boxing

The Key–Yeo fights gave an enormous boost to boxing in Singapore, setting the stage for the 1930s, a decade that many would go on to describe as the “golden age of boxing”. In 1930, one of Singapore’s earliest sports magazines – The Sportsman – was launched with boxing’s popularity reflected in the enormous space devoted to it.41 Schoolboys who could not afford tickets to fights collected and exchanged posters. Some even cut out photos of their favourite boxers from newspaper articles to create entire albums. In 1931, another entertainment venue, Great World, was established with regular, well-attended fight nights.42

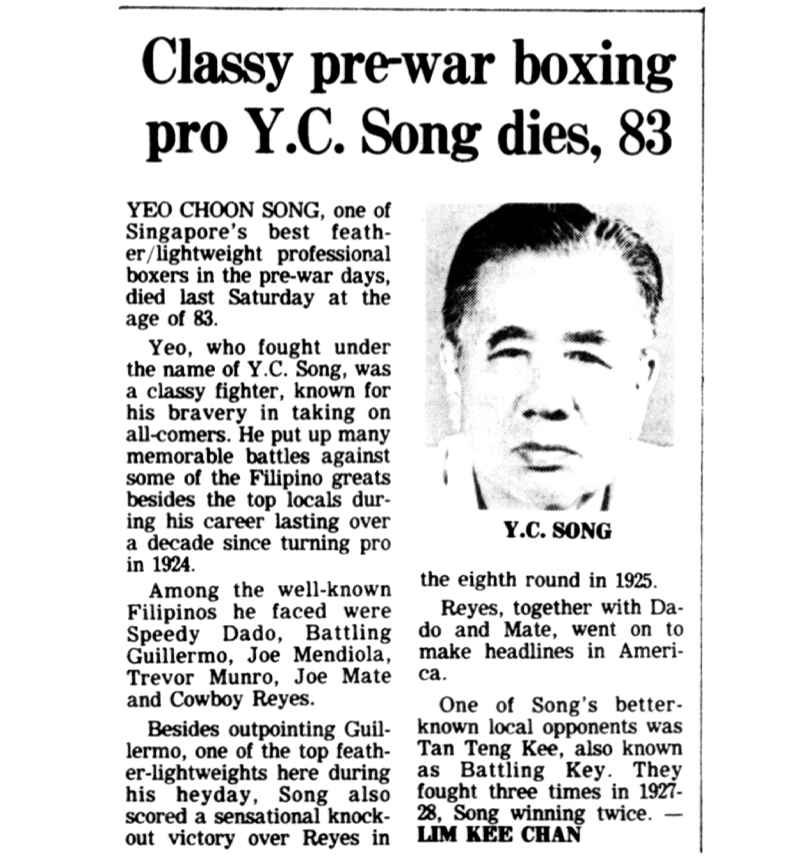

For the two men who had done so much for the sport though, the end was long drawn. After establishing himself as the best local boxer, Yeo struggled with injuries – one to his dominant left hand proving particularly nettlesome. In 1931, when he was only 25, Yeo announced his retirement due to “personal reasons”, having only fought a handful of bouts since that historic evening in 1928 (by defeating Battling Key), when the world had appeared to be in his grasp.43

Two years later, Yeo reappeared in the ring and carried on until 1935, when his final fight against the middling Al Nichlos ended in a draw.44 As far as written records are concerned, Yeo seemed to have dropped off the pages of history. A retrospective look at his career in 1947 bemoaned the fact that “had he come under the wing of an experienced trainer-manager”, he might have become as famous as the man he had dethroned in 1928.45 Yeo’s disappearance was characteristically understated: even during his fighting days, he had never been the most colourful of characters, letting his fists to do all the talking.

Battling Key, on the other hand, simply refused to give up boxing even after his losses to Yeo had made it clear his best days were behind him. Promoters were wary of backing an ageing fighter and in the 1930s, Key was reduced to traipsing round with a scrapbook under his arm, pleading with his former acquaintances in the boxing fraternity to give him another chance. Eventually, the Singapore Boxing Board of Control – formed sometime in the early 1930s to ensure boxer safety – banned him from fighting in the colony on account of his health.46

Still adamant, Key was “determined to try and come back”. He found some backers in Seremban where, in late 1934, he twice fought an obscure opponent called Young Felix and won both. The fights were modest affairs and after the latter, Key was robbed of even his paltry $30 purse on the way back to Singapore. “Once the idol of Malayan boxing and used to handling thousands of dollars!” lamented a contemporary observer.47

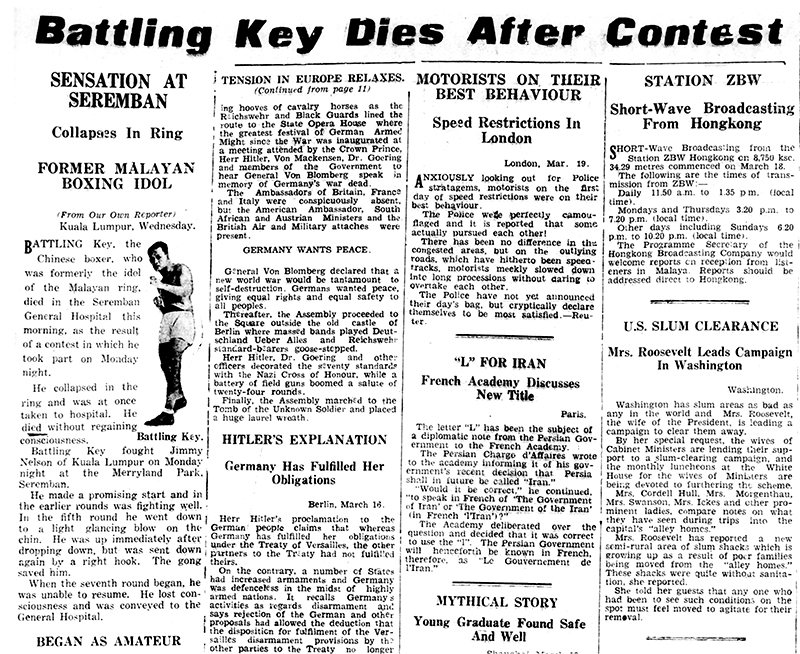

Unfortunately, a match on 19 March 1935 was Key’s swan song. He was lined up against Jimmy Nelson from Kuala Lumpur. After a promising start in the earlier rounds, Key went down after a “light glancing blow on the chin” in the fifth round. He got up immediately but was sent down again with a right hook. When the seventh round began, he lost consciousness and was admitted to the local general hospital.48

On 20 March 1935, nine months before Yeo fought for the last time, Battling Key, the former Malayan boxing idol, died without regaining consciousness. He was just 37 years old.49

Meanwhile, Yeo outlived his erstwhile opponent and died on 20 February 1988 at the age of 83. In his obituary, the Straits Times described him as “a classy fighter, known for his bravery in taking on all-comers”.50

Abhishek Mehrotra is a researcher and writer whose interests include media and society in colonial Singapore, urban toponymy and post-independence India. He is working on his first book – a biography of T.N. Seshan, one of India’s most prominent bureaucrats. The book, commissioned by HarperCollins, is slated for release in 2025. Abhishek is a former Lee Kong Chian Research Fellow (2021–22).

Abhishek Mehrotra is a researcher and writer whose interests include media and society in colonial Singapore, urban toponymy and post-independence India. He is working on his first book – a biography of T.N. Seshan, one of India’s most prominent bureaucrats. The book, commissioned by HarperCollins, is slated for release in 2025. Abhishek is a former Lee Kong Chian Research Fellow (2021–22).Notes

-

“New Advertisements,” Straits Maritime Journal and General News, 15 July 1896, 5. (From Newspaper SG) ↩

-

“A Marsupial Pugilist,” Straits Budget, 9 June 1896, 12. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

H.L. Hopkin, “Boxing Nights in Singapore,” Straits Times, 7 December 1927, 8. (From NewspaperSG). When newspapers advertised the bout as the “flyweight championship of Malaya”, several readers complained that the title was undeserved. The Malaya Tribune, rather sensibly, responded that there were “no formal championship competitions for boxers in Singapore, or anywhere else in Malaya”. And it went on to add, “Meanwhile, who can dispute any man’s right to claim any title except by fighting him for it?” See “Boxing,” Malaya Tribune, 8 July 1921, 5. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Lim Kee Chan, oral history interview by Chong Ching Liang, 18 April 1999, transcript and MP3 audio, Reel/Disc 6 of 13, National Archives of Singapore (accession no. 0001770), 105–06. ↩

-

Joseph R. Svinth, “The Origins of Philippines Boxing, 1899–1929,” Journal of Combative Sport, July 2001, https://ejmas.com/jcs/jcsart_svinth_0701.htm. ↩

-

No record of a Tait brothers’-owned circus travelling to Singapore in 1920 is available in the archives. Edwin Tait did, however, bring a circus over as part of the Malaya-Borneo exhibition in 1922. ↩

-

Lim Kee Chan, oral history interview, 18 April 1999, Reel/Disc 6 of 13, 105–06. ↩

-

Nick Aplin and Quek Jin Jong, “Celestials in Touch: Sport and the Chinese in Colonial Singapore,” in Sport in Asian Society: Past and Present, ed. J.A. Mangan and Fan Hong (London; Portland, Or.: Cass, 2003), 70. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. R 796.095 SPO) ↩

-

Teresa Oei, “My Uncle, The Peranakan Boxing Champion,” The Peranakan Association Newsletter (December 1995): 3–4, https://www.peranakan.org.sg/magazine/1995/1995_Issue_5.pdf. ↩

-

Locals called Emerald Hill Road, on which the Palladium was located, tang leng tiam yia yee hang (“Tanglin Cinema Street” in Teochew). ↩

-

“Boxing,” Straits Times, 15 August 1921, 10. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Such was the sport’s popularity that in one of the three fights – it is not known which – between Battling Key and Johnny Carvalho, the Sultan of Johor bet $5,000, presumably on the Johor man. See Seconds Out, “Chinese and Boxing in Malaya,” Pinang Gazette and Straits Chronicle, 28 January 1935, 12. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Last Night’s Boxing Sensation,” Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, 4 August 1922, 12. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Lim, “‘Key’ Never Quit Even When Chips Were Down,” Straits Times, 12 April 1981, 37. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Battling Key Is Willing,” Straits Times, 15 August 1922, 10. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Herman Rippa, “Battling Key – Battler and Philanthropist,” Sunday Tribune, 28 September 1947, 10. (From NewspaperSG). ↩

-

“Boxing,” Straits Times, 15 October 1923, 10; “First Real Local Champion,” Morning Tribune, 6 November 1937, 8. (From NewspaperSG). ↩

-

“Boxing.” Almost immediately, the Battling Key – Young Pelky fight attained legendary status in Singapore’s boxing circles. In later years, varying claims would be made about the size of the audience – ranging from 6,000 to 12,000. See, for example, “First Real Local Champion” and Rippa, “Battling Key – Battler and Philanthropist.” ↩

-

Rippa, “Battling Key – Battler and Philanthropist.” ↩

-

Filemon G. Salaysay, “Heartaches of a Promoter,” Singapore Free Press, 16 January 1954, 7. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“The Big Fight,” Malaya Tribune, 21 July 1922, 8. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Boxing,” Malaya Tribune, 4 January 1924, 8. (From NewspaperSG). Similar syndicates mushroomed across the region – the Penang Boxing Syndicate and the Oriental Boxing Syndicate being two others frequently mentioned in that era’s newspapers. ↩

-

“Box: Song Knocks Out Cowboy Reyes,” Straits Times, 7 January 1927, 10. (From NewspaperSG). This is not to imply that there weren’t other local champion boxers in Singapore at the time. The Eurasian Walley brothers, Boy and Bud, were considered legends in the flyweight category with the former coming close to winning the world crown. See Boy Walley, “The Pride of Malaya,” The Sportsman 2, no. 9 (6 May 1931): 10. (From NUS Libraries) ↩

-

Lim Kee Chan, “Song Did Not Believe in Second-Best Performance,” Straits Times, 26 April 1981, 27. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Singapore Boxing,” Pinang Gazette and Straits Chronicle, 6 October 1925, 13. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Boxing: Friday March 4 at Happy Valley,” Malaya Tribune, 3 March 1927, 7; “Key–Song To-Night,” Malaya Tribune, 4 March 1927, 10. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Sporting News: Boxing,” Malaya Tribune, 5 March 1927, 10. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

The description of the evening’s events has been adapted from “Last Night’s Results,” Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser (1884–1942), 5 March 1927, 20. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Song Wins Well Over Key,” Straits Times, 13 August 1927, 10. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Key and Song Ready for Big Fight,” Malaya Tribune, 4 October 1928, 10. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“The Battling Key-Y.C. Song Fight,” Malaya Tribune, 26 September, 1928, 10 (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Song Beats Key for Second Time,” Straits Times, 6 October 1928, 10. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Several issues of The Sportsman are available in NUS Libraries and provide a fascinating insight into the state of sport in the colony at the time. These can be accessed at digitalgems.nus.edu.sg/collection/11092/items. ↩

-

“T.F. Hwang Takes You Down Memory Lane,” Straits Times, 28 June 1975, 14. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Y.C. Song to Retire From Boxing,” Straits Times, 20 June 1931, 13. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Leighton”, “Amie Raphael Outpoints Alde While the Crowd Yawns,” Straits Times, 7 December 1935, 15. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Herman Rippa, “Y.C. Song, Red Warren & Dudley Cambrooke,” Sunday Tribune (Singapore), 12 October 1947, 11. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Battling Key Dies After Contest,” Malaya Tribune, 20 March 1935, 12. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Lim Kee Chan, “Boxing Pro Choon Song Dies,” Straits Times, 24 February 1988, 25. (From NewspaperSG) ↩