The Making of the Causeway

When the Causeway was built 100 years ago, it was the largest engineering project to be undertaken in Malaya. Building it required overcoming significant engineering challenges.

The official opening of the Causeway on 28 June 1924 was a historic event that marked the physical joining of Singapore with the Malay Peninsula, and indeed the rest of continental Asia. The lavish ceremony that took place was presided over by Laurence Nunns Guillemard, Governor of the Straits Settlements and High Commissioner of the Federated Malay States (FMS), in the presence of Sultan Ibrahim of Johor. More than 400 guests – including Malay nobility, dignitaries and prominent government officials – from the FMS, Straits Settlements and Johor attended the event.1

Today, a hundred years later, the Causeway has become one of the busiest overland border crossings in the world, with 300,000 travellers daily.2 It was the only physical link between Singapore and the Malay Peninsula for almost three quarters of a century until the Second Link – connecting Tuas in Singapore to Tanjung Kupang in Gelang Patah, southwest Johor – opened in 1998.3

Before the Causeway existed, crossing the Straits of Johor was cumbersome. People here had to take the train to Woodlands on the Singapore-Kranji Railway, which had opened in 1903,4 and then board one of two steam-powered ferry boats – aptly named Singapore and Johore – across the strait to Johor Bahru and vice versa.

Towards the end of the first decade of the 20th century, the train and ferry services were under increasing pressure to keep pace with the rapidly growing movement of people and goods across the Johor Strait. In 1909, “wagon-ferries” were introduced to help reduce congestion. Also known as train-ferries, these were barges specially outfitted with railway tracks, each capable of transporting up to six train carriages by sea to connect with the railway lines at either end. They complemented the passenger ferry boats and, for the first time, allowed the seamless carriage of goods from ferry to railway without having to unload and load goods.

The wagon-ferries were so successful that demand for its services soon surpassed capacity. In addition to the volume of traffic, the escalating maintenance costs of the wagon-ferries raised concerns about their long-term viability. A better solution was needed.5

In 1917, W. Eyre Kenny, the director of public works for the FMS, suggested building a rubble causeway across the strait.6 The idea quickly gained traction and the Causeway proposal won the support of Edward Lewis Brockman, Chief Secretary to the FMS, and Arthur Henderson Young, Governor of the Straits Settlements and High Commissioner of the FMS.

The British government appointed consultant engineers Messrs Coode, Matthews, Fitzmaurice & Wilson to prepare detailed plans for the Causeway, which were presented to the FMS, Straits Settlements and Johor governments in 1918. The Straits Settlements government formally approved the Causeway project the next year.7 That same year, the Johor government also passed a law to authorise the construction of a causeway.

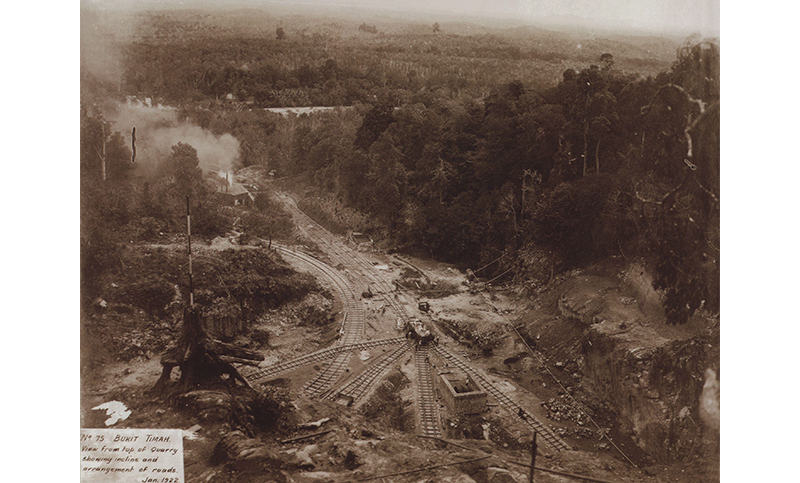

The consultant engineers proposed a rubble causeway about 18 m wide that would stretch just over a kilometre between the two territories. The raw materials for the rubble would come from granite quarries in nearby Pulau Ubin and Bukit Timah in Singapore.

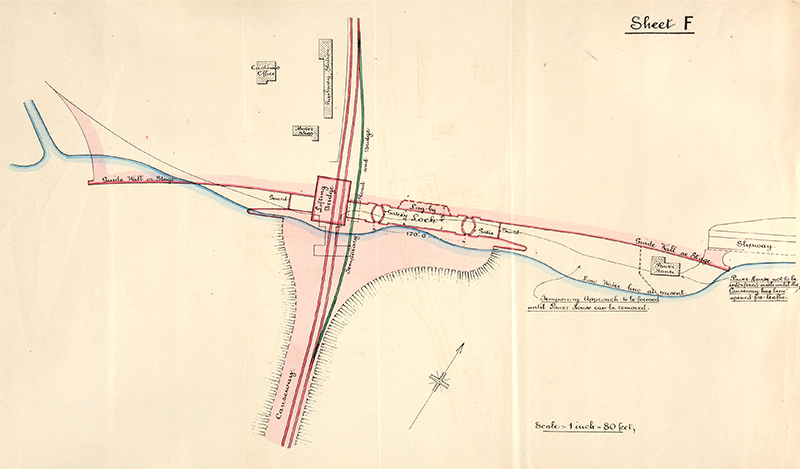

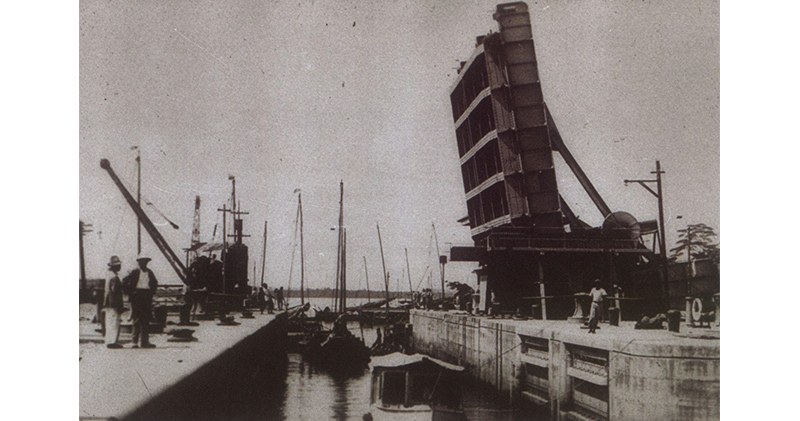

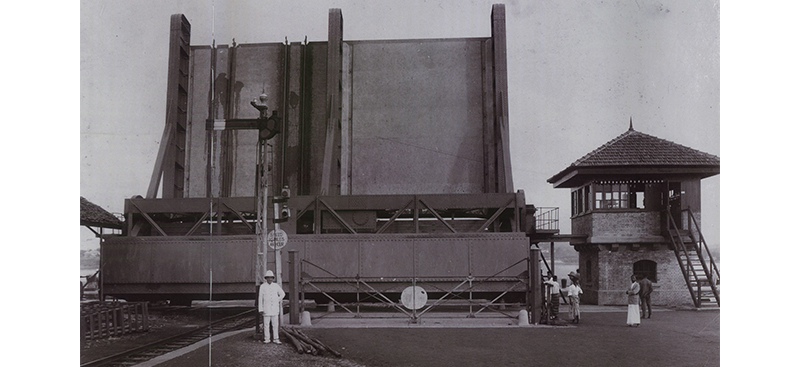

Part of the engineering challenge in building the Causeway was that at the Johor end, it had a channel, also known as a lock, to allow local vessels to pass through. The lock, about 52 m long and 10 m wide at the gate, needed a double set of floodgates as the water flow between the channel would change direction with the tide. A rolling lift-bridge, a kind of drawbridge, was installed to carry the road and railway tracks over the lock. The moving part of the bridge alone weighed 570 tons and raising it took eight and a half minutes. In addition, a tunnel 3.5 m wide and 2.4 m high was built below the lock to allow waterpipes to be run to Singapore.8

Construction work began in 1919 and was completed in 1924. Thousands of workers were involved, and the project would eventually cost Johor, the Straits Settlements and the FMS an unprecedented 17 million Straits dollars.

In 2011, the National Archives of Malaysia and the National Archives of Singapore jointly published The Causeway, a book about the history of the land bridge between the two countries. The following extract, mainly from chapter three of the book, details the construction challenges involved in building the Causeway.

The Grand Plan – Engineering the Causeway (1919–23)

The Causeway project was technically challenging by the standards of its time and would be the largest engineering project in Malaya at the time. Construction would take an estimated four to five years, and would require the labour of over 2,000 workers as well millions of tons of stone and other building matertials.9

Tidal studies were carried out in 1917, and design features were incorporated to limit changes in the water level at the Causeway to control possible damage to its structure and surroundings, as well as to manage the strength of the currents passing through its lock to allow for safe navigation.10

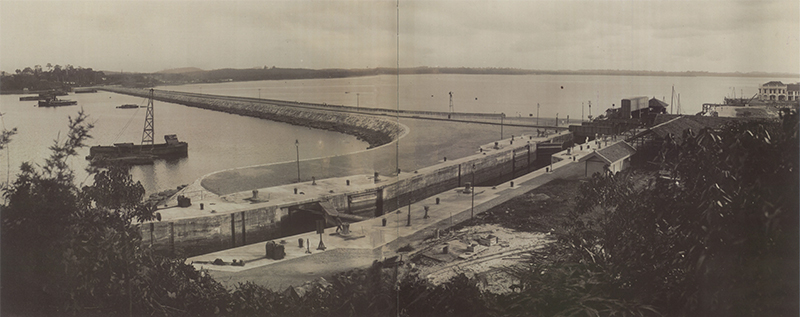

A detailed plan of the Causeway’s construction site was prepared by Messrs Coode, Matthew, Fitzmaurice & Wilson in 1917, with recommendations to change the Causeway’s orientation. The proposed Causeway would be 3,465 ft long (1,056 m) from bank to bank, with a width of 60 ft (18 m) sufficient to carry two lines of metre-gauge railway tracks, a 26-foot-wide (8 m) roadway, with space reserved for the laying of water mains at a later date.

The contract to construct the Causeway was awarded on 30 June 1919 to Messrs Topham, Jones & Railton Ltd. of London, a renowned engineering firm that had successfully carried out several major large-scale public projects in Singapore.

The company was behind the construction of two of colonial Singapore’s most important dockyards – King’s Dock at Keppel Harbour built in 1913, the largest dry dock in Asia, and the massive 24.5-acre Empire Dock at Tanjong Pagar Harbour completed in 1917, the largest wet dock in Singapore. The firm had also taken on major reconstruction work at the Tanjong Pagar wharves in 1917, to the commendation of the colonial government.11 It thus had on hand experienced engineers, workmen and the necessary tools and equipment for the job. A period of five years and three months was allowed for the completion of all related works.

Construction on the Causeway commenced in August 1919 in Johor Bahru, beginning with the excavation of the lock channel.12 The governments involved decided to complete the lock first to minimise disruption to shipping during the rest of the construction. The lock was placed at the Johor end of the Causeway because it had more suitable approaches than the Woodlands side, and the approach would also cause less disruption to the existing ferry services.

Since the lock would occupy the site of the pontoon landing stage for the passenger ferry launches at Johor Bahru station, it was necessary to first provide a new landing stage. The pontoon and connecting bridge were removed and reinstalled on 14 August 1919 at the new site, located clear of the works at the west end of the west wing-wall of the lock. For the convenience of train passengers, a temporary covered walkway was built between the railway station and the new site of the pontoon. This transfer was achieved without causing any interruption to passenger ferry traffic.

The quarry at Pulau Ubin, which was about 16 miles (26 km) away and had been opened in 1907 for the Singapore harbour-works, was reopened in 1919 to supply rubble and crushed stone for the Causeway. Four of the ten hopper barges ordered from England for the transport of stone from quarries in Singapore to the Causeway had been delivered during the year, along with one of two large steam tugs also ordered from England, which were designed to pull those barges. A smaller tug and a steam launch had also been purchased locally in 1919 to expedite the transportation of stone.

The 1919 Johor Annual Report proudly reported that work on the Causeway is “destined to connect Johor with Singapore by road and rail proceeds day and night”.13

Laying the Foundation Stone

In 1920, with work on the Causeway progressing satisfactorily, it was deemed proper to hold a ceremony to mark the laying of its foundation stone. Governor Laurence Nunns Guillemard and the chief secretary agreed to have the ceremony on 24 April 1920. It was to be conducted from on board the steam yacht Sea Belle, anchored in the middle of the Johor Strait. The occasion would also coincide with Guillemard’s first official visit to Johor.

The Causeway’s foundation laying ceremony took place amid an economic boom in British Malaya. International prices of Malaya’s main exports, such as rubber and tin, had reached record levels in the first half of 1920 and the future looked bright.

However, a sudden unexpected worldwide economic depression hit in mid-1920, which severely affected Malaya’s economy and lasted until the latter part of 1922. Thus, the bulk of the Causeway’s construction took place in the midst of serious economic dislocation. Under the bleak economic conditions, the Causeway project came under increasing public scrutiny and criticism.

At around the same time, the British Admiralty raised objections to the dimensions of the lock channel, proposing that it be expanded to at least 400 ft (122 m) in length and 75 ft (23 m) in breadth – about double its originally planned size – to accommodate passage of large British warships. Although this suggestion was eventually dropped because of the engineering difficulties and hefty additional costs involved,14 these two factors almost convinced the FMS and Straits Settlements governments to abandon the Causeway project.

By then, the construction of the lock at the Johor end was well advanced and the north wall of the lock was half completed. In addition, the first two lengths of the east and west wing-walls of the lock had been built, and the eastern portion of the watertight cofferdam enclosing the south wall of the lock was ready for closing, allowing workers to work on the lock in dry conditions.

In addition, output from the granite quarry on Pulau Ubin had improved significantly, and from February 1921 additional supplies started arriving from the Bukit Timah quarry. In June the same year, the depositing of rubble commenced on the Johor side of the works, allowing the construction of the Causeway’s superstructure to proceed from both sides of the strait. Some 2,337 men were engaged in the Causeway’s construction that year.15

At the end of 1921, all excavation and concrete works had been completed on the lock, along with construction on most of its north wall. Good progress was also made on the lock’s south wall, east wing-wall and on the installation of the lock’s double set of floodgates. The first of the 5-foot-diameter (1.5 m) culverts was also completed at the Johor end, and groundwork commenced on the rolling lift-bridge.

By July 1922, rubble deposits on both sides of the Causeway had reduced the gap remaining in the superstructure to just 1,300 ft (396 m) at low tide. At this point, a coating of rubble was deposited over the gap to prevent any scouring of the bottom due to the increased velocity of currents in the narrowing channel. Work on the superstructure of the Causeway resumed after this precautionary measure had been taken.

On 1 January 1923, the lock was handed over to the Federated Malay States Railways (FMSR) to begin operations, and all shipping through the Johor Strait were subsequently diverted through the lock as the advanced stage of construction had made it increasingly hazardous for ships to navigate the strait. To prevent unauthorised entry of vessels, chain defences were placed at both ends of the lock. In addition, red and green navigation lights were placed on either side of the entrances to indicate whether the lock was closed or opened to traffic. It has been recorded that at least 30 vessels passed through the lock during the first month of its operation and 13,513 craft passed through the lock in 1923. With the opening of the lock to traffic in January 1923, construction work on the Causeway’s superstructure resumed.16

The installation of the rolling lift-bridge was completed in January 1923, and the channel between Johor and Singapore was sealed up on 1 June 1923.

The Causeway Opens

The year 1923 was a milestone of sorts in the history of the Causeway. The Causeway was first opened to goods trains on 17 September 1923,17 and the wagon-ferry service between Johor Bahru and Woodlands was withdrawn from that date. By this time, the wagon-ferries were running more than 11,000 trips a year with 7,777 trips recorded from 1 January to 16 September 1923, the final year of its operations.18

On 27 September 1923, the general manager of the FMSR sought the sanction of Sultan Ibrahim to open the Causeway and the railway for the public carriage of passengers from 1 October 1923. Approval was granted on 30 September 1923, followed by the publication of Gazette Notification No. 489 in the Johore Government Gazette.19 On 1 October 1923, the passenger steam launch ferry service across the strait between Johor Bahru and Woodlands was withdrawn after over a decade of service.

The first passenger train across the Causeway was the night mail, which left Kuala Lumpur on 30 September 1923, arriving at Tank Road station at 7.41 am on 1 October. On board was none other than P.A. Anthony, the former general manager of FMSR. The Straits Times described the first passenger train as “a big train, including twelve bogey carriages and forming an imposing display of rolling stock for the auspicious occasion”. And perhaps with a tinge of nostalgia, the Straits Times reporter added: “The ferry across the Straits is now a thing of the past, all trains crossing the Causeway.”20 The daily schedule included a day mail and a night mail from both destinations. On 1 October 1923, the Johor Causeway Toll was also introduced for both passenger and goods traffic conveyed over the Causeway, replacing the earlier ferry charges.

The Causeway was officially completed on 11 June 1924. The final phase of the works included finishing touches to the east wing-wall of the lock, repainting the insides of the lock gates, cleaning and painting the capstans, fairleads and machinery pit covers, and grouting the joints of the pitching behind the east end of the lock. The roadway was completed except for a small portion at the Woodlands end, which was deferred until the railway track was moved to its final position — the second railway track had not been laid yet at the time of the opening. The crossing gates were handed over to the Railway Department in June.

The successful completion of the Causeway three months ahead of the stipulated date was a creditable reflection on the diligence, expertise and experience of the engineers and contractors. Credit is also due to the staff and labourers, who worked in temperatures that could reach 89 to 90 degrees Fahrenheit (27 to 32 degrees Celsius) and who also bore with rainy spells that accounted for an average loss of two working days a month.

The Causeway’s opening in June 1924 was a historic milestone in Singapore-Malaya relations. More than a physical link, the opening of the Causeway was a fitting symbol of the close ties and shared history that bound both territories together. This abiding connection would remain long after Malaya – later Malaysia – and Singapore had become separate independent nations.

This is an edited extract from The Causeway (2011), jointly published by the National Archives of Malaysia and the National Archives of Singapore. The book is available for reference at the Lee Kong Chian Reference Library and for loan at selected public libraries (call nos.: RSING 388.132095957 CAU and SING 388.132095957 CAU).

Notes

-

“The Causeway,” Straits Times, 28 June 1924, 9. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Woodlands Checkpoint to Be Redeveloped in Phases; Construction to Commence in 2025,” Immigration & Checkpoint Authority, 29 January 2024, https://www.ica.gov.sg/news-and-publications/newsroom/media-release/woodlands-checkpoint-to-be-redeveloped-in-phases-construction-to-commence-in-2025. ↩

-

Leong Chan Teik, “Second Link at Tuas Opens Without Fanfare,” Straits Times, 3 January 1998, 1. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“The Singapore-Kranji Railway,” Pinang Gazette and Straits Chronicle, 16 April 1903, 3. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

The National Archives, United Kingdom, Johore Annual Report 1910–1913. (From National Archives of Singapore, accession no. CO 715/1); Federated Malay States Railways Report for the Year 1912. ↩

-

Proceedings of the Federal Council of the Federated Malay States for the year 1917, p. B57. ↩

-

Proceedings of the Federal Council of the Federated Malay States, 13 November 1917, B57; The National Archives, United Kingdom, Extract of Letter from Messrs Coode, Matthews, Fitzmaurice & Wilson to Crown Agents. (From National Archives of Singapore, accession no. CO 273/462), 267. ↩

-

“The Causeway: A Great Engineering Work Completed,” Straits Times, 27 June 1924, 9. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

The National Archives, United Kingdom, “Johore State Railway Construction – Johore Singapore Connection Causeway,” 1 January 1916–31 December 1926. (From National Archives of Singapore, accession no. CAOG 10/50 E358/4A), 39–45. ↩

-

“The King’s Dock,” Straits Times, 27 August 1913, 10; “Empire Docks,” Straits Times, 7 February 1919, 47; “Empire Dock,” Straits Times, 26 October 1917, 10. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“FMS Railways: Annual Report of the General Manager,” Straits Times, 18 October 1921, 11. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Federated Malay States Railways Report for the Year 1920. ↩

-

The National Archives, United Kingdom, “Colonial Office. Straits Settlements. Original Correspondence. Offices (Except Miscellaneous),” 12 January 1921–7 March 1921. (From National Archives of Singapore, accession no. CO 273/512) ↩

-

Proceedings of the Federal Council of the Federated Malay States, 13 December 1921, C499; “Facts and Figures: Memorandum of the High Commissioner,” Straits Times, 24 November 1922, 10. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Paper No, 4547, “The Johore Causeway”, D. Paterson, 222/1923, Federated Malay States Annual Report 1923. ↩

-

Federated Malay States Railways Report for the Year 1923. ↩

-

“Johore Causeway: Opening to Passenger Traffic To-day,” Straits Times, 1 October 1923, 10. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

SS 2170/1923: GA 463/1923. ↩