How the CPF Scheme Came to Be

If things had turned out differently, Singapore would now be using a national pension scheme instead of the Central Provident Fund scheme.

By Lim Tin Seng

The Central Provident Fund (CPF) scheme is a key part of Singapore’s social security system today. For most Singaporeans, the money in their CPF account allows them to buy a home, pay for healthcare expenses and plan for their retirement. As a result, the CPF scheme is deeply embedded into the fabric of life in Singapore today.

However, the CPF scheme was only established on 1 July 1955. Before then, life for the majority of workers in Singapore was much more uncertain as the social security net was considerably more threadbare.

Retirement Benefits for Workers

Before the CPF scheme was set up, only a few employees had retirement benefits. Some workers were on a pension scheme (also known as a defined benefit scheme). This is a retirement plan where employees and/or employers contribute to a collective fund and, upon retirement, employees receive a predetermined monthly payment until death.1 This scheme was mostly offered in the civil service or by large foreign companies in Singapore at the time.

Some workers had access to a provident fund (also known as a defined contribution scheme). This is a retirement plan where both employees and employers contribute to the employees’ individual accounts, and the retirement benefits depend on their contributions and investment performance. The Singapore Municipality and some private companies such as Singapore Cold Storage, Fraser and Neave, and the Singapore Swimming Club were some employers that had established a provident fund for their employees before the CPF was created.2

While some employers might offer “a thousand dollars or two” as a gratuity to their employees when they retired, the majority did not offer any retirement benefits at all.3 As a result, most workers were left to fend for themselves after retiring. As the Singapore Standard observed in April 1951: “[I]n 90 cases out of a 100, for those employed in non-governmental services, the thought of retirement is a nightmare… For when the employee leaves his job he would be losing his only means of livelihood. After his long service he leaves his post the way he came in – almost penniless. Many of them end their last days in misery and poverty.”4

In March 1949, Singapore started to look for a suitable retirement benefit scheme for workers. This came after Lim Yew Hock, a Legislative Council member representing trade union interests, introduced a motion in the Legislative Council calling for “legislation for social security, and that a committee should be appointed by Government at an early date to investigate and make recommendations on medical care, sickness and unemployment benefits, and old age pensions”.5

Lim had earlier spoken up about non-existent social security measures for workers. “This lamentable lack of social security for non-Government workers is highly deplorable and I know Government’s sympathies are with them,” he said. “But so long as these sympathies are not translated into protective legislative measures the workers will have cause to reflect sadly that this Government is still run by capital as it was before the war.”6

Although the Legislative Council fully supported the motion, Colonial Secretary P.A.B. McKerron emphasised that the scheme needed to be not only “desirable and workable, but also financially sound”, as “everything you get has got to be paid for”.7

The Central Provident Fund Bill

It took two years before Tan Chye Cheng of the Progressive Party introduced the Central Provident Fund (CPF) Bill at the Singapore Legislative Council on 22 May 1951. The delay sparked criticism and was even viewed by some political parties as “a publicity stunt” by the Progressive Party. However, the real reason for the delay was the party’s struggle to draft the CPF Bill as “there was no precedent which could be found in the English Statute Books”.

Although the Progressive Party was aware that India and the government of the Federation of Malaya were introducing their own provident funds at the time, it felt those versions were “not a suitable precedent”. Consequently, lawyers in the United Kingdom were sought to draft the CPF Bill “on instructions of the Progressive Party” before it was presented to the Singapore Legislative Council in May 1951. The bill aimed to “establish a compulsory central provident fund for all employees except those whose employers have already provided comparable or better retiring benefits”.8

The proposed legislation called for workers who were earning at least $100 per month and not covered by any retirement benefit scheme to make a monthly 5 percent contribution of their salary to a central provident fund. The contribution would be matched by employers, and the accumulated amount would then draw an interest rate of 3 percent. Once the worker reached the age of 55, he or she would be able to withdraw the accumulated amount.9

Unions and employees reacted positively to the introduction of the CPF Bill, commenting that it was “a measure long overdue”. The Singapore Clerical Union hoped that the bill would be “rushed” through the Legislative Council as “much time had been already lost”. The Clerical Union also suggested that contributions by employers be arranged “in a graduated scale” so that firms making “handsome profits” would contribute more.10

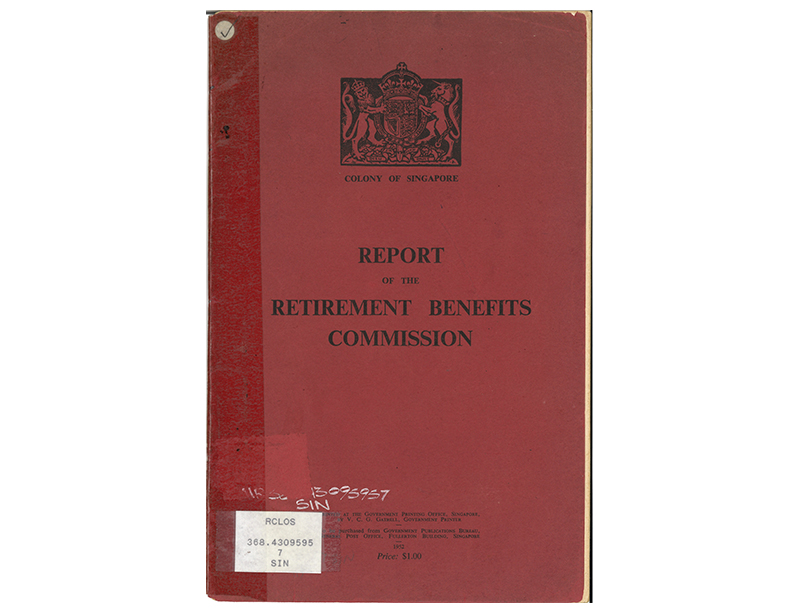

While the CPF Bill was being introduced, a separate Retirement Benefits Commission was convened on 19 May 1951 by Franklin Gimson, governor of Singapore, to explore alternative retirement scheme options. Headed by F.S. McFadzean, director of the Colonial Development Corporation, the commission was tasked to “investigate the best possible retirement benefits scheme for Singapore workers”. This led to a delay in the progress of the CPF Bill in the Legislative Council as the latter now had to consider the commission’s recommendations.11

When the commission submitted its report to the government in February 1952, it recommended a pension scheme instead of a provident fund. The proposed pension scheme would require employees to make a weekly contribution of 60 cents until retirement. This amount would be matched by their employers. Upon retirement at age 55, the employee would receive a monthly pension of $30 till death.12 The commission felt that the pension scheme would require a shorter timeframe of “a few years” to be ready, whereas the provident fund scheme “would not be able to provide adequate amounts for retirement until about 1970”, and those who were middle-aged or older at the time could “never truly benefit under it”.13

Adopting the Provident Fund Scheme

When the Retirement Benefits Commission’s recommendations were presented to the Legislative Council during the second reading of the CPF Bill on 17 June 1952, the pension scheme was rejected in favour of the central provident fund scheme.14 The Legislative Council believed that a provident fund was a more suitable and sufficient retirement mechanism. “From the views gathered by me, employees prefer to receive a lump sum on retirement instead of a paltry $25 or $35 per month,” said Tan, who had introduced the CPF Bill in 1951. S. Jaganathan, general secretary of the Singapore Trade Union Congress, commented that the $30 monthly pension was “not enough for a family to live on”.

According to a Straits Times survey conducted in May 1951, most unions, particularly non-government ones, felt that a provident fund “would not only be acceptable to all types of employers, but would be very fair to both employers and employees because it cuts both ways and gives both labour and management a sense of joint responsibility for the workers’ future”.15

After receiving support in the Legislative Council, the CPF Bill was sent to a select committee, which among other things, was tasked to determine how the CPF should be administered.16

After 16 months of deliberation, the select committee put forth a number of amendments, including the proposal to create a “separate full-time organisation” in the form of a board to administer the provident fund. Comprising a chairman “with appropriate qualifications” and six members that were of equal “representative of the Government and of both employers and employees”, the board would be appointed by the governor on a three-year term. Elected members of the Legislative Council and City Council were not allowed to serve on the board to ensure that the provident fund was “entirely removed from the realm of politics”.17

Other additional amendments included expanding the coverage to include employees earning between $25 and $500 per month; revising the interest to 2.5 percent; allowing employees such as those in the civil service who were already covered by an existing retirement benefit scheme to be exempted from making a contribution; and setting a $500 salary cap for contributions.

On 24 November 1953, the amended CPF Bill was passed by the Legislative Council. The news was welcomed by both employers and employees. Lim Seow Eng, managing director of Ho Hong Oil Mills, said the compulsory measure would benefit all parties as “there would be security for the workers and better working results for the company”.18

Timber merchant Gan Thean Hoo felt that the CPF would foster closer ties between employers and employees and benefit society in general. “Employers will be able to set aside something every month for the welfare of those who bring them the profits,” he said. “The fund will encourage employees to stick to their jobs. Government will have money in hand for investment purposes, which will also benefit the general public and the Colony.” Agreeing that the CPF would bring long-term benefits to workers, John Tan, a commercial assistant, said: “Working people will not begrudge the small monthly sacrifices which will benefit them in later years. All my friends welcome the fund.”19

An Unexpected Delay

The new CPF Board, with E.L. Peake as the chairman, was up and running as early as January 1954. To prepare for the CPF scheme, which was slated to come into effect on 1 May 1955, one of board’s first tasks was to register all employers both in the civil and private sectors, who would then provide the fund with details of their employees. This registration exercise began on 4 January 1955 and by 30 March, some 17,000 firms with 60,000 employees had joined the fund.20

However, just two days before the Central Provident Fund Ordinance was scheduled to take effect, Minister for Labour and Welfare Lim Yew Hock unexpectedly announced a delay. This came in response to criticism that the 5 percent CPF contribution would reduce the already low wages of many workers to a level “too low to provide for basic necessities”. A.E.M. Geddes, secretary of Great Eastern Life Assurance Co. Ltd., observed that the objection to CPF contributions came not from employers but from employees, noting that “[s]ome workmen seem to regard their contributions as a kind of tax instead of a form of saving subsidised by their employers”.21

An amending bill was quickly drafted and rushed through the Legislative Assembly under a Certificate of Urgency. The amendment exempted workers earning less than $200 from contributing to the fund, although their employers still had to pay their share. The bill was passed on 29 June 1955, allowing the fund to come into effect on 1 July 1955.22

Revisiting the Pension Scheme Proposal

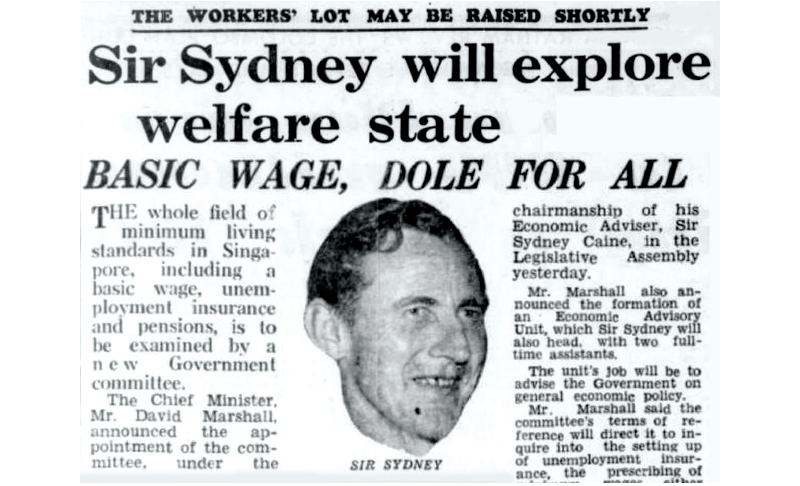

The colonial government continued to seek alternative views on how the CPF should be expanded to cover not only the entire population, including casual workers and the self-employed, but also others in need such as the unemployed and the sick. On 21 November 1955, Chief Minister David Marshall announced the formation of the Committee on Minimum Standards of Livelihood headed by Sydney Caine, Economic Adviser to the Government and Vice-Chancellor of the University of Malaya. This committee was tasked with “establishing a minimum living standard in Singapore” by providing a basic wage and unemployment insurance, as well as improving the adequacy of existing social security programmes, including the CPF.23

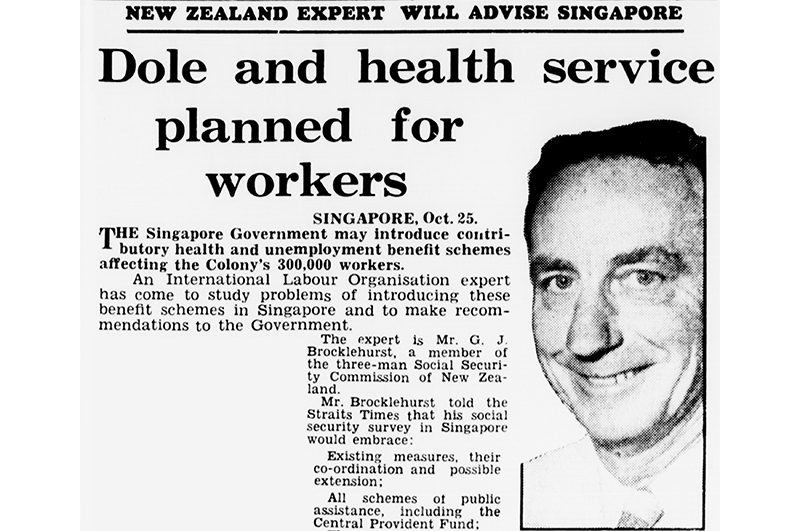

Concurrently, a study led by International Labour Organization expert, G.J. Brocklehurst, was initiated in October 1955 to assess the feasibility of introducing “contributory health and unemployment benefit schemes affecting the Colony’s 300,000 workers”. This was later expanded to evaluate the overall effectiveness of existing social security initiatives including the CPF.24

In their findings, both Caine and Brocklehurst found shortcomings with the CPF scheme. Caine felt that the provident fund was “in essence one of compulsory saving, not of social insurance”,25 while Brocklehurst concluded that it was “not adequate as a social security measure”.26 They recommended replacing the CPF with a new integrated social security system governed by a department of social security. This system would include a contributory pension scheme and a public assistance scheme, providing coverage not only for retirees but also for widows, the sick and those on maternity leave. However, unemployment benefits would be introduced at a later stage.27

Caine and Brocklehurst also recommended varying contribution rates based on wage levels, with lower-paid employees contributing a lower percentage. Benefits should be adjusted so that lower-paid workers would receive a larger proportion of their wages compared to higher-paid workers.28

The idea of creating a new social security system received mixed reactions. Some trade union leaders praised the extension of social security coverage but preferred it to be voluntary. C. Muthucumaru, secretary of the Singapore Federation of Unions of Government Employees, said: “We have been asking for some sort of social insurance scheme to safeguard our members. Mr. Brocklehurst’s scheme is a good one because it will benefit everyone, but we think it should be on a voluntary basis.”

Some trade unions were wary of the new system though, especially since it might replace the CPF. John Chung, president of the Business Houses Employees Union, argued that the CPF should continue and that “any form of social security measures should be in addition to the Fund”. A.M. Nair, vice president of the Singapore Trade Union Congress, felt that it was “not necessary” to replace the CPF to broaden social security coverage. He suggested that the government could finance the proposed social security scheme through a levy on luxury goods, a special tax on totalisator lottery and the introduction of a social welfare lottery.29

On 14 January 1958, the government appointed a select committee, led by L.C. Goh, permanent secretary to the Ministry of Labour and Welfare, to review and integrate the recommendations by Caine and Brocklehurst into a legislation for a new social security system. This system would cover all employees over 18 years old earning more than $40 a month, including casual workers, with the option for the self-employed to join voluntarily.30

Employee contribution rates for the new social security fund would vary according to their monthly wages, ranging from $1 to $30 per month, while employers were to contribute a fixed 6 percent of the employee’s wages, up to a maximum of $30. Retirement, sickness and maternity benefits were standardised, with higher proportions for lower-paid workers.31

Benefits were calculated based on a percentage of wages and the employee’s family status. For example, single individuals would receive 30 percent of wages up to $100 per month and 15 percent of any excess, capped at $90 per month. Those with dependents would receive 50 percent of wages up to $100 per month and $25 of any excess, capped at $150 per month. Retirement pensions would begin at age 60, while sickness benefits were limited to three months per year and maternity leave up to eight weeks. Benefits for widows were determined by numerous factors such as age, whether they had children and the length of the marriage.32

The committee also noted that once the new social security legislation came into effect, the CPF would be discontinued, and members who had contributed to the fund would be eligible to have their savings either refunded or transferred to the new social insurance fund. The proposed legislation for the new social security scheme, dubbed the “Social Security Bill”, was unveiled in March 1959 but its progress was put on hold due to the Legislative Assembly general election in June that year.33

Retaining the Central Provident Fund

The 1959 Legislative Assembly general election ushered in a new era. At the election, the People’s Action Party (PAP) swept into power, taking 43 out of 51 seats. The new administration took a different stance on social insurance. Labour and Law Minister K.M. Byrne stressed that the government would “first have to fulfil its declared policy, and to attend to other urgent problems before embarking on any social security scheme”. These issues included unemployment, establishing a trade union house, organising trade unions, setting up an industrial court and amending the Labour Ordinance.34

The government later clarified that the CPF was “not meant to provide unemployment assistance because it covered a savings scheme”.35 In fact, it was cautious about transforming Singapore into a welfare state.36 As founding Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew wrote in his memoir: “Watching the ever increasing costs of the welfare state in Britain and Sweden, we decided to avoid this debilitating system. We noted by the 1970s that when governments undertook primary responsibility for the basic duties of the head of a family, the drive in people weakened. Welfare undermined self-reliance… The handout became a way of life.”37

Instead of a welfare state, Lee believed that the CPF could encourage self-reliance among Singaporeans. “The CPF has made for a different society. People who have substantial savings and assets have a different attitude to life,” he wrote. “They are more conscious of their strength and take responsibility for themselves and their families.”38

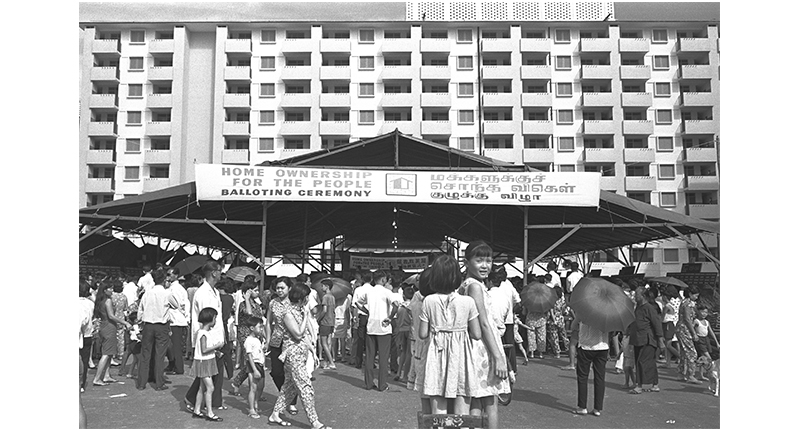

Lee also said that the CPF system “needed time to build up” before it could prove its worth, including allowing CPF savings to be used for important social needs such as home ownership. “Only then,” he wrote, “would people not want their individual savings put into a common pool for everyone to have the same welfare ‘entitlement’.”39

The Central Provident Fund Today

The CPF scheme has undergone numerous changes in the decades following its establishment. Beyond retirement, today Singaporeans can also use the money in their CPF accounts for housing, insurance, investment and education. However, even as the CPF scheme has expanded, the system has also not deviated from its original goal, i.e., to ensure that Singaporeans have funds for their retirement.

Over the years, the scheme has been tweaked to improve the retirement aspect. Originally, members were able to fully withdraw their savings when they retired. In 1987, the Minimum Sum Scheme was introduced which held back an amount, the so-called “minimum sum”, out of which the CPF savings are doled out monthly until it runs out. In 2009, the CPF Life annuity scheme was introduced. Under this scheme, members receive payouts for life.

The CPF annuity scheme has also been modified since 2009 to allow people to save more for their retirement. From 1 January 2025, the Enhanced Retirement Sum (ERS), which is the amount that goes into the annuity scheme, will be raised to four times the Basic Retirement Sum. Previously, the enhanced amount was three times the basic one. This change will allow those who are able to save more to get more per month as a payout.

In 2025, the ERS will be $426,000, up from $308,700. According to the CPF Board, those who turn 55 in 2025, and who top up to the new maximum amount, will be able to receive more than $3,000 a month for life from age 65.40

Lim Tin Seng is a Senior Librarian with the National Library, Singapore. He is the co-editor of Roots: Tracing Family Histories – A Resource Guide (2013), Harmony and Development: ASEAN-China Relations (2009) and China’s New Social Policy: Initiatives for a Harmonious Society (2010). He writes regularly for BiblioAsia.

Lim Tin Seng is a Senior Librarian with the National Library, Singapore. He is the co-editor of Roots: Tracing Family Histories – A Resource Guide (2013), Harmony and Development: ASEAN-China Relations (2009) and China’s New Social Policy: Initiatives for a Harmonious Society (2010). He writes regularly for BiblioAsia. Notes

-

Chia Ngee-Choon, Central Provident Fund (Singapore: Institute of Policy Studies: Straits Times Press Pte Ltd, 2016), 1. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSING 368.40095957 CHI); Linda Low and T.C. Aw, Housing a Healthy, Educated and Wealthy Nation Through the CPF (Singapore: Times Academic Press for the Institute of Policy Studies, 1997), 5–8. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSING 368.4095957 LOW) ↩

-

Chia, Central Provident Fund, 1; “Municipal Provident Fund,” Straits Budget, 17 March 1896, 2; “Provident Funds,” Straits Times, 16 November 1940, 10. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Central Provident Fund Bill: 2nd Reading,” Proceedings of the Legislative Council, Colony of Singapore, 17 June 1952, B194. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RCLOS 328.5957 SIN) ↩

-

“Fear of Old Age,” Singapore Standard, 20 April 1951, 6. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Social Security Move in Colony,” Straits Times, 16 March 1949, 1. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“S’pore Social Security Plan Sought,” Straits Times, 14 March 1949, 5. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Laycock Seeks India’s Aid,” Sunday Tribune, 19 March 1950, 3; “Workers Fund Bill for Council,” Straits Times, 24 October 1950, 5; “Benefit Bill for Committee,” Straits Times, 23 May 1951, 5. (From NewspaperSG); “Central Provident Fund Bill: 1st Reading,” Proceedings of the Legislative Council, Colony of Singapore, 22 May 1951, B79. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RCLOS 328.5957 SIN); “Central Provident Fund Bill: 2nd Reading,” B194. ↩

-

“Provident Fund for All Workers Proposed,” Straits Times, 17 January 1951, 4; “Provident Fund to Be Made Compulsory,” Indian Daily Mail, 21 January 1951, 4; “Text of Progressive Party’s Provident Fund Bill,” Indian Daily Mail, 22 January 1951, 4. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

George Rasiah, “Employers Welcome Proposed Compulsory Provident Fund,” Singapore Standard, 18 January 1951, 2. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Colony of Singapore, Report of the Retirement Benefits Commission (Singapore: Government Printing Office, 1951), 1. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RCLOS 368.43095957 SIN); “Retirement Commission,” Straits Times, 29 June 1951, 5; “‘Choose Benefit Scheme First’,” Singapore Free Press, 20 May 1952, 5. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Pension Plan Urged for S’pore,” Straits Times, 28 February 1952, 7; Trade Unionist, “Workers Are Still Waiting,” Straits Times, 17 October 1953, 10. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Pension Plan Urged for S’pore”; Report of the Central Provident Fund Study Group (Singapore: National University of Singapore, Dept. of Economics and Statistics, 1985), 1–4. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 368.40095957 CEN) ↩

-

“Govt Backs Progs’ ‘Funds Bill’,” Singapore Standard, 18 June 1952, 2. (From NewspaperSG); “Central Provident Fund Bill: 2nd Reading,” B198. ↩

-

“Trade Unions ‘In the Dark’,” Straits Times, 30 May 1951, 4. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Provident Fund Plan Is Tabled,” Singapore Standard, 21 October 1953, Page 9. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

G.T. Boon, “Provident Fund Gets a Big Welcome,” Singapore Free Press, 1 December 1953, 12. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Hurry Along Those Forms, Firms Urged,” Straits Times, 30 March 1955, 2; “They Will Run the Big Fund,” Straits Times, 29 January 1954, 4. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Provident Fund Is Put Off,” Straits Times, 29 April 1955, 5; “Scheme Hold Up Affects 15,000,” Straits Times, 13 May 1955, 12. (From NewspaperSG); Colin Cheong, Saving for Our Retirement: 50 Years of CPF (Singapore: SNP Editions, 2005), 22–23. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSING 368.40095957 CHE) ↩

-

“Provident Fund Will Commence on July 1,” Indian Daily Mail, 12 May 1955, 4. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Sir Sydney Will Explore Welfare State,” Straits Times, 22 November 1955, 7. (From NewspaperSG); Report of the Central Provident Fund Study Group, 4–5; Low and Aw, Housing a Healthy, Educated and Wealthy Nation Through the CPF, 15–16. ↩

-

“Dole and Health Service Planned for Workers,” Straits Budget, 27 October 1955, 17. (From NewspaperSG); Report of the Central Provident Fund Study Group, 5–6; Low and Aw, Housing a Healthy, Educated and Wealthy Nation Through the CPF, 16–17. ↩

-

Committee on Minimum Standards of Livelihood, Report of the Committee on Minimum Standards of Livelihood (Singapore: Government Printing Office, 1957), 43. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RCLOS 331.2 SIN [RFL]) ↩

-

International Labour Office, Report to the Government of Singapore on Social Security Measures (Singapore: Government Printing Office, 1957), 33. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RCLOS 368.40095957 INT) ↩

-

Committee of Officials Established to Examine the Recommendations of the Brocklehurst and Caine Committee Reports (Singapore: Government Printing Office, 1959), 42. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RCLOS 362.95951 SIN-[RFL]) ↩

-

Committee of Officials Established to Examine the Recommendations of the Brocklehurst and Caine Committee Reports, 42; “Plan for Illness, Maternity, Old Age Benefits,” Straits Budget, 25 March 1959, 10. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Hands Off the Provident Fund Say Unionists,” Singapore Free Press, 27 September 1958, 5; “TUC Will Urge Govt. to Tax Luxury Goods,” Singapore Free Press, 5 March 1958, 5. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Social Security Plan for S’pore,” Singapore Standard, 1 May 1958, 7; “Experts to Draft Welfare Scheme,” Straits Budget, 15 January 1958, 9; “Plan for Illness, Maternity and Age Benefits,” Straits Times, 19 March 1959, 1. (From NewspaperSG); Report of the Central Provident Fund Study Group, 6; Low and Aw, Housing a Healthy, Educated and Wealthy Nation Through the CPF, 18–19. ↩

-

Committee of Officials Established to Examine the Recommendations of the Brocklehurst and Caine Committee Reports, 42. ↩

-

Committee of Officials Established to Examine the Recommendations of the Brocklehurst and Caine Committee Reports, 42. ↩

-

Committee of Officials Established to Examine the Recommendations of the Brocklehurst and Caine Committee Reports, 45; “Social Security Scheme for All in Singapore,” Singapore Standard, 19 March 1959, 4. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Social Security: ‘Not for 2 More Years’,” Straits Times, 22 October 1959, 16. (From NewspaperSG); Report of the Central Provident Fund Study Group, 6–7; Chia, Central Provident Fund, 14–15; Low and Aw, Housing a Healthy, Educated and Wealthy Nation Through the CPF, 20. ↩

-

“C.P.F. – A Savings Scheme: Ahmad.” Straits Times, 18 November 1961, 4. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Chia, Central Provident Fund, 14–15; Low and Aw, Housing a Healthy, Educated and Wealthy Nation Through the CPF, 20–21. ↩

-

Lee Kuan Yew, From Third World to First: The Singapore Story, 1965–2000: Memoirs of Lee Kuan Yew (Singapore: Marshall Cavendish Editions, 2015), 126. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSING 959.5705092 LEE) ↩

-

Lee, From Third World to First, 127. ↩

-

Lee, From Third World to First, 126–27. ↩

-

“What Is the Change to the Enhanced Retirement Sum in 2025?” Central Provident Fund Board, last updated 18 October 2024, https://www.cpf.gov.sg/service/article/what-is-the-change-to-the-enhanced-retirement-sum-in-2025. ↩