Providing Independent and Non-Partisan Views: The Nominated Member of Parliament Scheme

The Nominated Member of Parliament Scheme was set up to present more opportunities for Singaporeans to participate in politics. But its implementation in 1990 was not without controversy.

By Benjamin Ho and John Choo

On Thursday, 20 December 1990, Maurice Choo Hock Heng, a cardiologist, and Leong Chee Whye, a businessman and former senior civil servant, were sworn into Parliament. What made this particular swearing ceremony historic is that the two men were Singapore’s first nominated members of Parliament (NMPs).1

Unlike elected members of Parliament (MPs), NMPs are appointed by the president of Singapore on the recommendation of a Special Select Committee appointed by Parliament, and do not belong to any political party nor represent any constituency. The role of NMPs is to bring more independent voices into Parliament.

Even though they were first appointed in 1990, the idea of having non-elected MPs was actually proposed by founding Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew as far back as the early 1970s.

“Seats for the Universities?” was the headline that greeted the readers of the Straits Times on the morning of 4 September 1972.2 Two days earlier, the barely seven-year-old nation had witnessed its second general election as an independent state. The ruling People’s Action Party (PAP) made a “clean sweep” at the polls, winning all 57 contested seats and 69.02 percent of the 760,472 votes cast.3

At the post-election press conference on 3 September, Lee publicly floated the idea of having parliamentary seats set aside for higher institutions of learning to promote the growth of an intelligent and constructive opposition. These could be graduates of the then University of Singapore, Nanyang University, Teachers’ Training College, Singapore Polytechnic and Ngee Ann Technical College. “I think the problem of getting an intelligent, constructive Opposition has got to be solved. Singapore has not got the kind of people going into politics who are likely ever to develop into a coherent, constructive Opposition,” he said. “They should be intelligent enough to point out where the Government was wrong.” However, he stressed that the government needed more time to mull over it before coming to a decision.4

The idea possibly stemmed from a three-century-old system in Britain, which saw as many as 15 parliamentary seats reserved for English, Scottish, Irish and Welsh universities in the 1930s. Although this practice was abolished in 1948, the idea was the catalyst for key changes in Singapore’s parliamentary system in the subsequent decade.5

Seeding a Constitutional Change

The idea gained traction 12 years later, although in a different form when the ruling party introduced the concept of non-constituency members of Parliament (NCMPs). These would be “defeated Opposition candidates who have polled the highest votes nationwide in a general election, subject to a minimum of 15 percent of ballots cast”.6 Under the proposed amendment to the constitution, at least three Opposition MPs would enter Parliament, if not as full MPs, then as NCMPs.

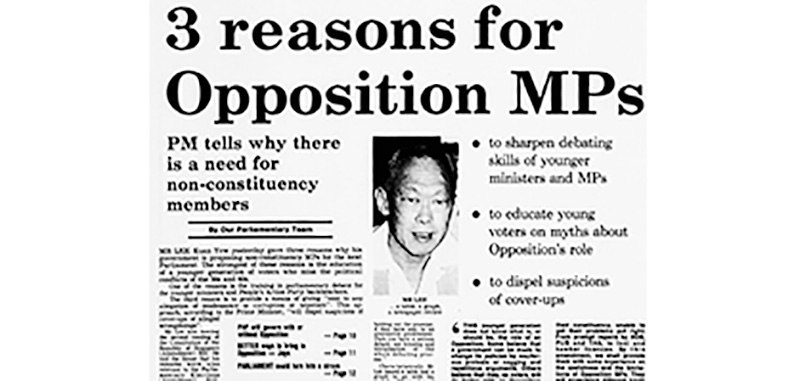

Speaking at the second reading of the Constitution of the Republic of Singapore (Amendment) Bill in July 1984, Lee, who was still the prime minister, argued that the presence of Opposition members could provide opportunities for younger ministers and MPs to hone their debating skills. It would also educate the younger generation of voters, who had never experienced political conflicts in Parliament, about the role and limitations of a constitutional Opposition. Finally, having non-PAP MPs would “ensure that every suspicion, every rumour of misconduct, will be reported to the non-PAP MPs, at least anonymously” and “will dispel suspicions of cover-ups of alleged wrongdoings”.7

Summing up, Lee said that the NCMP scheme would “enable Singapore to have a good and effective government” and “at the same time, satisfy those who feel that there should be a few Opposition MPs represented in Parliament”.8

Legislative changes to the Constitution and the Parliamentary Elections Act were made in August 1984.9 After the general election in December that year, two Opposition candidates, Chiam See Tong of the Singapore Democratic Party and J.B. Jeyaratnam of the Workers’ Party, were voted into Parliament, leaving one NCMP seat on offer. However, the two top highest-scoring defeated Opposition candidates declined to take the seat and it was left vacant until the next general election.10

After the general election in September 1988, two NCMP seats were accepted by Lee Siew Choh and Francis Seow from the Workers’ Party. However, Seow was disqualified in December the same year after he was fined for tax evasion.11

A Prickly Beginning

In 1989, then First Deputy Prime Minister Goh Chok Tong introduced the Constitution of the Republic of Singapore (Amendment No. 2) Bill that would allow for the appointment of NMPs. The timing of this move was to align with the PAP government’s vision in 1984 to strengthen the political system by offering more opportunities for political participation among Singaporeans.12

At the second reading of the bill in Parliament on 29 November 1989, Goh said that the bill aimed “to evolve a more consensual style of government where alternative views are heard and constructive dissent accommodated”. He said that this should be seen in the wider context of political innovations like NCMPs, and the establishment of Group Representation Constituencies and Town Councils.13

The bill sought to provide for the appointment of a maximum of six NMPs. They would be appointed by the president of Singapore on the nomination of a Special Select Committee that is in turn appointed by Parliament. Nominated persons are subject to the same stringent qualifications and requirements as those standing for election. NMPs are politically non-partisan and should not belong to any political party.14

PAP MP for Pasir Panjang GRC Bernard Chen lent support to the bill but gave a hint on the tone of the debate that is to come. “On this note, I would like to support the First Deputy Prime Minister although I know there will be many others whose support may not be so forthcoming,” he said.15

Several PAP MPs spoke in strong terms against the bill, even lamenting their inability to vote against it under the Party’s Whip. PAP MP for Siglap Abdullah Tarmugi cautioned that this change would create the perception that the proposal was “tantamount to an indictment of the existing system and of the elected MPs we now have, especially the backbenchers in the House”. He asked: “Are we not creating the impression that MPs are not really bringing up enough solid and diverse views in this Parliament that we need to bring in others to this Chamber to provide such views?”16

Dixie Tan, PAP MP for Ulu Pandan, evoked the spirit of the Constitution, which is that “each and every citizen of 21 years and above has a vote” and the “votes of citizens collectively decide the persons that will sit in the Parliament Chamber”. She cautioned that this basic principle would be violated if nominated MPs were allowed into the House.17

PAP MP for Fengshan Arthur Beng’s concluding remarks summed up the tone of the two-day debate: “Sir, I cannot support this Bill. However, as a PAP Backbencher, I say this again, like my colleagues, well realising that I will be subjected to the Party Whip. This is the constraint upon us, and I guess we will have to continue to live a ‘schizophrenic’ political life – speaking against yet voting for a Bill.”18

Chiam See Tong, the MP for Potong Pasir and the sole Opposition MP, opposed the amendments to the constitution. “I would say that when nominated MPs are installed in our Parliament, they are just like fish out of water. They should not be in our Parliament. They should be tossed back to the universities or statutory bodies or businesses or other work places where they came from. If these people want to be in Parliament, then let them do so by the proper means. Come forward and put themselves through the electoral process. I do not think it is right for anyone to enjoy the privileges and prestige of being a Member of Parliament without earning that right in a parliamentary election.”19

Concluding the end of the contentious debate, Goh offered a possibility of a “sunset” or “self-destruct” clause to allay the concerns of MPs. He said: “After a certain time, maybe four or five years from now, either before the next general elections or soon after, if the Bill, which if it is enacted becomes law, does not bring us the benefits which I expect, and if Members of Parliament are still not convinced by the wisdom of having such people in Parliament, that law will self-destruct unless it is renewed again by Members in this House.” His final words to the MPs were: “Give this a try. We lose nothing by trying.”20

Eventually, a clause was included in the bill to give each Parliament the discretion to decide whether it wants NMPs during its term.21 After the bill was passed into law on 31 March 1990 and the NMP scheme came into effect on 10 September that year, there was still little clarity on the roles and expectations of NMPs. In fact, the scheme remained an experiment even when the first two NMPs – Maurice Choo and Leong Chee Whye – were appointed on 22 November 1990.22

Getting Buy-In

With the scheme in place, a basic question of implementation arose: Who would serve as these NMPs? Few members of the public who fulfilled the criteria stipulated in clause 3(2) of the new Fourth Schedule of the Constitution volunteered themselves. The clause states that “The persons to be nominated shall be persons who have rendered distinguished public service, or who have brought honour to the Republic, or who have distinguished themselves in the field of arts and letters, culture, the sciences, business, industry, the professions, social or community service or the labour movement.”23

Not many were like Toh Keng Kiat, a haematologist in private practice, who was an NMP from 1992–94. “If you’re looking for someone who can be meaningful in giving an input in, say, medical problems, I’m ready to serve,” the physician shared in an oral history interview.24 “I have always been conscious of the fact that everyone should make a contribution to the country,” he told the Business Times in 1992.25

His contemporary, orthopaedic surgeon Kanwaljit Soin, an NMP for three terms from 1992–96, “solicited support from friends because she decided that there should be more women’s voices in Parliament”. However, she was quick to add that she did not want “women’s issues to be seen as women against men, or to be seen as extreme advocate of women’s rights”. “But I do think that we need more female representation in organisations,” she said.26

Many of the early NMPs were approached by PAP leaders to apply for the role. They were frequently caught off-guard, being people for whom participation in formal politics was the furthest from their minds. Some of them even had to read up on the scheme, not having followed the parliamentary debates closely, if at all.

In his contribution to the 2023 book, The Nominated Member of Parliament Scheme, Maurice Choo wrote that he was approached by a government minister and asked if he would consider serving as an NMP. “Not knowing much about what was involved, I asked for time to study the scheme… Among the arguments, the one I felt was the most important was about modifying the perception that Singapore was a ‘one-party parliament’ with an excessively autocratic government.”27 Choo served as an NMP from 1990–91.

The appeal of the NMP role varied from person to person. For someone like businessman Chuang Shaw Peng, who served from 1997–1999, accepting the offer was something of a compromise position, having previously turned down earlier invitations to join the PAP. Describing why he was reluctant to be a party member, he recalled: “Once you’re a member of a party, you have to at least align with them. You cannot say something different, something contrary to what the majority of the PAP members want to do or what they have proposed to do. And then, I cannot say anything anymore. Maybe that led to the view that maybe I’m suitable to be an NMP.”28

Feeling the Ground

Beyond merely being able to contribute to issues on a personal basis, some of the early NMPs saw the scheme as a way to represent the interest of particular groups. Chuang Shaw Peng described his presence as being a loose form of sectoral representation, complementing the system of electoral representation. “If I represent the construction industry, I’ve got a few hundred thousand people with me, you know what I mean?… Construction industry is a big industry; the financial one is a very big industry; education is another big industry. So we bring in… the trade viewpoint or the industry viewpoint, which can be more constructive in formulating policy. Because policies are based on industries, not based on constituencies.”29

That said, prior to his entry into Parliament, Chuang stepped down as president of the Singapore Contractors Association Limited to avoid a perceived conflict of interest.

Imram Mohamed, the first Malay-Muslim NMP, similarly resigned from his committee position in the newly established Association of Muslim Professionals.30 He went on to serve for two terms as an NMP, from 1994–96 and briefly from 1996–97.

The ambiguity of whether NMPs represented themselves or a specific sector was gradually resolved over time, beginning with the introduction of “proposal panels” in 1997 representing three functional groups: business and industry, the professions and the labour movement.

It was then Leader of the House Wong Kan Seng who had proposed in Parliament on 5 June 1997 to invite leaders of certain key functional groups to nominate their members for the Special Select Committee’s consideration. This was in addition to getting members of the public to nominate suitable and interested individuals. “[M]any of the former NMPs came from these key sectors, though they were not specifically nominated by the organisations which make up these functional areas,” he said. “What is new about this approach is that we will formally and systematically request these organisations to get together and nominate some individuals from among their membership for the consideration of the Special Select Committee.”31

In July 1997, the three “proposal panels” (business and industry, the professions and the labour movement) were officially formed to “fine-tune and improve the selection process”. “We hope they will come up with the best people, because the whole idea of this new feature in the selection process must be ultimately to enhance the NMP scheme,” said then Speaker of Parliament Tan Soo Khoon.32

Making History

On 23 May 1994, Walter Woon, then vice-dean of the Faculty of Law, National University of Singapore, made history by becoming the first NMP (he served for three terms from 1992–96) to introduce a private member’s bill, the Maintenance of Parents Bill, in Parliament.33 The bill was passed without debate at its third reading on 2 November 1995.34

The Maintenance of Parents Act came into force on 1 June 1996, along with the establishment of the Tribunal for the Maintenance of Parents. This is the first public law that originated from a private member’s bill since Singapore’s independence in 1965. The legislation provides for Singapore residents aged 60 years and above, who are unable to maintain himself or herself adequately, to claim maintenance from their children either in the form of a monthly allowance or any other periodical payment or a lump sum.35

The passing of Woon’s Maintenance of Parents Bill gave other NMPs the confidence to table their own bills. Kanwaljit Soin’s Family Violence Bill introduced on 27 September 1995 did not succeed, but many of its proposals were later incorporated into amendments to the Women’s Charter on 1 May 1997.36 Following consultation with then Minister for Health George Yeo, Imram Mohamed withdrew his motion to introduce the Human Organ Transplant (Amendment) Bill on 10 October 1996.37

Changes to the NMP Scheme

On 5 June 1997, Wong Kan Seng moved a motion in Parliament to increase the maximum number of NMPs from six to nine. In his speech, he assessed that the NMPs had performed well and wanted Parliament to allow views that “may not be canvassed by the PAP or opposition members” and help to fill the void left by the loss of two elected opposition MPs.38

In July the same year, the Constitution of the Republic of Singapore (Amendment) Act 1997 was passed to raise the maximum number of NMPs to nine.39 Among the first batch of nine NMPs was lawyer Shriniwas Rai, who was sworn in on 1 October 1997.40 In his oral history interview, he reflected on the importance of an NMP being an independent voice to “articulate the feeling of the nation, the concern of the community”.41 He served one term and said that “one term is enough, let’s give others an opportunity”.42

In August 2002, the Constitution of the Republic of Singapore (Amendment) Act 2002 was passed in Parliament to extend the NMP term of service from two to two-and-a-half years.43 This administrative change was to avoid going through the NMP nomination process three times for a full five-year term of Parliament. For instance, in the ninth term of Parliament from 1997–2001, there were NMPs who served around a month before Parliament was dissolved.44

In 2010, two decades after the scheme was introduced, NMPs had become more comfortable in their role and the public also had a better understanding of what NMPs do. In the same year, the Constitution of the Republic of Singapore (Amendment) Act 2010 was enforced, abolishing the requirement for a resolution to be passed before NMPs may be appointed.45

NMPs have now been entrenched as permanent fixtures in Singapore politics. The current serving NMPs are Usha Chandradas, Keith Chua, Mark Lee, Ong Hua Han, Neil Parekh Nimil Rajnikant, Razwana Begum Abdul Rahim, Jean See Jinli, Syed Harun Alhabsyi and Raj Joshua Thomas.46

This was one of the earliest and longest-continuous running projects undertaken by the then Oral History Unit (renamed Oral History Centre in 1993). The first oral history interview for this project by the unit was conducted in January 1980 with Peter Low Por Tuck, former PAP assemblyman for Havelock and parliamentary secretary (Finance) who was part of the group of 13 that broke away to form the Barisan Sosialis.

Available on Archives Online, the project is organised by time periods: 1945 to 1965, 1965 to 1985, 1985 to 2005 and 2005 to 2025 (www.nas.gov.sg/archivesonline/oral_history_interviews/). There are around 890 hours of such interviews publicly available. Among the former Nominated Members of Parliament whose interviews are accessible online are Chuang Shaw Peng (accession no. 004889), Imram Mohamed (accession no. 004884) and Shriniwas Rai (accession no. 004898).

Benjamin Ho is a Senior Specialist with the Oral History Centre, National Archives of Singapore. He has interviewed people from all walks of life covering the social, economic and political history of Singapore, and hopes to share these stories with a wider audience.

Benjamin Ho is a Senior Specialist with the Oral History Centre, National Archives of Singapore. He has interviewed people from all walks of life covering the social, economic and political history of Singapore, and hopes to share these stories with a wider audience.  John Choo is a Specialist with the Oral History Centre, National Archives of Singapore. He started his journey recording the experiences of individuals during the COVID-19 pandemic. Since then, he has sought to capture the life stories of other people who have contributed to society.

John Choo is a Specialist with the Oral History Centre, National Archives of Singapore. He started his journey recording the experiences of individuals during the COVID-19 pandemic. Since then, he has sought to capture the life stories of other people who have contributed to society. Notes

-

“Top Executive, Heart Specialist Picked As NMPs,” Straits Times, 21 November 1990, 1. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Seats for the Universities?” Straits Times, 4 September 1972, 1. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Clean Sweep for the PAP,” Straits Times, 3 September 1972, 1. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Tan Wang Joo, “In Quest of an Opposition,” Straits Times, 9 September 1972, 14. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“3 Reasons for Opposition MPs,” Straits Times, 25 July 1984, 1. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“3 Reasons for Opposition MPs”; “PAP Will Govern, With or Without an Opposition,” Straits Times, 25 July 1984, 10. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Parliament of Singapore, Constitution of the Republic of Singapore (Amendment) Bill, vol. 44 of Parliamentary Debates: Official Report, 24 July 1984, col. 1722, https://sprs.parl.gov.sg/search/#/report?sittingdate=24-07-1984; Parliament of Singapore, Parliamentary Elections (Amendment) Bill, vol. 44 of Parliamentary Debates: Official Report, 25 July 1984, col. 1835–46, https://sprs.parl.gov.sg/search/#/topic?reportid=004_19840725_S0002_T0004; Parliament of Singapore, Parliamentary Debates: Official Report, vol. 44, 24 August 1984, col. 1975, https://sprs.parl.gov.sg/search/#/report?sittingdate=24-08-1984. ↩

-

“PAP Wins All But Two,” Straits Times, 23 December 1984, 1; “Nair Yet to Decide on Non-constituency MP Seat,” Business Times, 24 December 1984, 14. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Conviction Disqualifies Seow as NCMP,” Straits Times, 10 January 1989, 1. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Parliament of Singapore, Constitution of the Republic of Singapore (Amendment No. 2) Bill, vol. 54 of Parliamentary Debates: Official Report, 29 November 1989, col. 695, https://sprs.parl.gov.sg/search/#/report?sittingdate=29-11-1989. ↩

-

Parliament of Singapore, Constitution of the Republic of Singapore (Amendment No. 2) Bill, col. 695. ↩

-

Parliament of Singapore, Constitution of the Republic of Singapore (Amendment No. 2) Bill, cols. 697–700. ↩

-

Parliament of Singapore, Constitution of the Republic of Singapore (Amendment No. 2) Bill, col. 709. ↩

-

Parliament of Singapore, Constitution of the Republic of Singapore (Amendment No. 2) Bill, col. 710 ↩

-

Parliament of Singapore, Constitution of the Republic of Singapore (Amendment No. 2) Bill, cols. 765–66. ↩

-

Parliament of Singapore, Constitution of the Republic of Singapore (Amendment No. 2) Bill, col. 765. ↩

-

Parliament of Singapore, Constitution of the Republic of Singapore (Amendment No. 2) Bill, cols. 734–35. ↩

-

Parliament of Singapore, Constitution of the Republic of Singapore (Amendment No. 2) Bill, vol. 54 of Parliamentary Debates: Official Report, 30 November 1989, col. 852, https://sprs.parl.gov.sg/search/#/report?sittingdate=30-11-1989. ↩

-

“Chok Tong’s Variation of His Original ‘Sunset’ Clause Adopted,” Straits Times, 18 March 1990, 20. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Republic of Singapore, Constitution of the Republic of Singapore (Amendment) Act 1990, No. 11 of 1990, Government Gazette Acts Supplement, https://sso.agc.gov.sg/Acts-Supp/11-1990/Published/19900407; “Novel: A Parliamentary Experiment,” in The Nominated Member of Parliament Scheme: Are Unelected Voices Still Necessary in Parliament? ed. Anthea Ong (Singapore: World Scientific Publishing Co Pte Ltd, 2023). (From NLB OverDrive) ↩

-

Republic of Singapore, Constitution of the Republic of Singapore (Amendment) Act 1990, Clause 3(2). ↩

-

Toh Keng Kiat, oral history interview by John Choo, 23 June 2023, MP3 audio, Reel/Disc 1 of 3, National Archives of Singapore (accession no. 004886), 24:31–24:48. ↩

-

“Dr Toh to Give Unbiased Views,” Business Times, 2 September 1992, 2. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Group Made Up of Diverse Individuals and Ideas,” Straits Times, 2 September 1992, 25. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Maurice Choo, “One Way,” in The Nominated Member of Parliament Scheme. ↩

-

Chuang Shaw Peng, oral history interview by John Choo, 25 April 2023, MP3 audio, Reel/Disc 1 of 2, National Archives of Singapore (accession no. 004889), 2:18–2:57. ↩

-

Chuang Shaw Peng, interview, 25 April 2023, Reel/Disc 1 of 2, 10:39–11:18. ↩

-

Imram Mohamed, oral history interview by John Choo, 3 April 2023, MP3 audio, Reel/Disc 1 of 2, National Archives of Singapore (accession no. 004884), 28:46–29:18. ↩

-

Parliament of Singapore, Nominated Members of Parliament, vol. 67 of Parliamentary Debates: Official Report, 5 June 1997, cols. 415–18, https://sprs.parl.gov.sg/search/#/report?sittingdate=05-06-1997. ↩

-

Tan Hsueh Yun, “Three Panels Formed to Propose NMP Candidates,” Straits Times Weekly Overseas Edition, 12 July 1997, 4. (From NewspaperSG). ↩

-

Warren Fernandez, “Woon’s Parents Bill: Easiest Part Is Over,” Straits Times, 24 May 1994, 23. (From NewspaperSG); Parliament of Singapore, Maintenance of Parents Bill – Introduction and First Reading, vol. 63 of Parliamentary Debates: Official Report, 23 May 1994, col. 37, https://sprs.parl.gov.sg/search/#/topic?reportid=025_19940523_S0003_T0006. ↩

-

Parliament of Singapore, Maintenance of Parents Bill (As Reported from Select Committee), vol. 65 of Parliamentary Debates: Official Report, 2 November 1995, cols. 210–13, https://sprs.parl.gov.sg/search/#/report?sittingdate=02-11-1995. ↩

-

Republic of Singapore, Maintenance of Parents Act 1995, 2020 rev ed, https://sso.agc.gov.sg//Act/MPA1995. ↩

-

Parliament of Singapore, Family Violence Bill – Introduction and First Reading, vol. 64 of Parliamentary Debates: Official Report, 27 September 1995, cols. 1536–38, https://sprs.parl.gov.sg/search/#/report?sittingdate=27-09-1995; Republic of Singapore, Women’s Charter (Amendment) Act 1996, No. 30 of 1996, Government Gazette Acts Supplement, https://sso.agc.gov.sg/Acts-Supp/30-1996/Published/19961011?DocDate=19961011. ↩

-

Parliament of Singapore, Human Organ Transplant (Amendment) Bill – Introduction and First Reading, vol. 66 of Parliamentary Debates: Official Report, 10 October 1996, cols. 627–28, https://sprs.parl.gov.sg/search/#/report?sittingdate=10-10-1996. ↩

-

Parliament of Singapore, Nominated Members of Parliament Motion, vol. 67 of Parliamentary Debates: Official Report, 5 June 1997 col. 417, https://sprs.parl.gov.sg/search/#/report?sittingdate=05-06-1997. ↩

-

Republic of Singapore, Constitution of the Republic of Singapore (Amendment) Act 1997, No. 1 of 1997, Government Gazette Acts Supplement, https://sso.agc.gov.sg/Acts-Supp/1-1997/Published/19970822?DocDate=19970822. ↩

-

“New Batch of NMPs Poised to Make Debut,” Straits Times, 2 October 1997, 3. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Shriniwas Rai, oral history interview by Benjamin Ho, 30 June 2023, MP3 audio, Reel/Disc 5 of 5,National Archives of Singapore (accession no. 004898), 43:51–44:03. ↩

-

Shriniwas Rai, interview, 30 June 2023, Reel/Disc 5 of 5, 43:00–43:30 ↩

-

Republic of Singapore, Constitution of the Republic of Singapore (Amendment) Act 2002, No. 24 of 2002, Government Gazette Acts Supplement, https://sso.agc.gov.sg/Acts-Supp/24-2002/Published/20020910?DocDate=20020910. ↩

-

Parliament of Singapore, Nominated Members of Parliament Motion, vol. 74 of Parliamentary Debates: Official Report, 5 Apil 2002 col. 629, https://sprs.parl.gov.sg/search/#/report?sittingdate=05-04-2002. ↩

-

Republic of Singapore, Constitution of the Republic of Singapore (Amendment) Act 2010, No. 9 of 2010, Government Gazette Acts Supplement, https://sso.agc.gov.sg/Acts-Supp/9-2010/Published/20100628170000?DocDate=20100628170000. ↩

-

“List of Current MPs,” Parliament of Singapore, last updated 13 March 2024, https://www.parliament.gov.sg/mps/list-of-current-mps. ↩