Forgotten Photographs of the 1952 Trip to Bali

A treasure trove of negatives found in an old shoebox sheds new light on a trip that led to an exhibition now regarded as a milestone in the history of Singapore art.

By Gretchen Liu

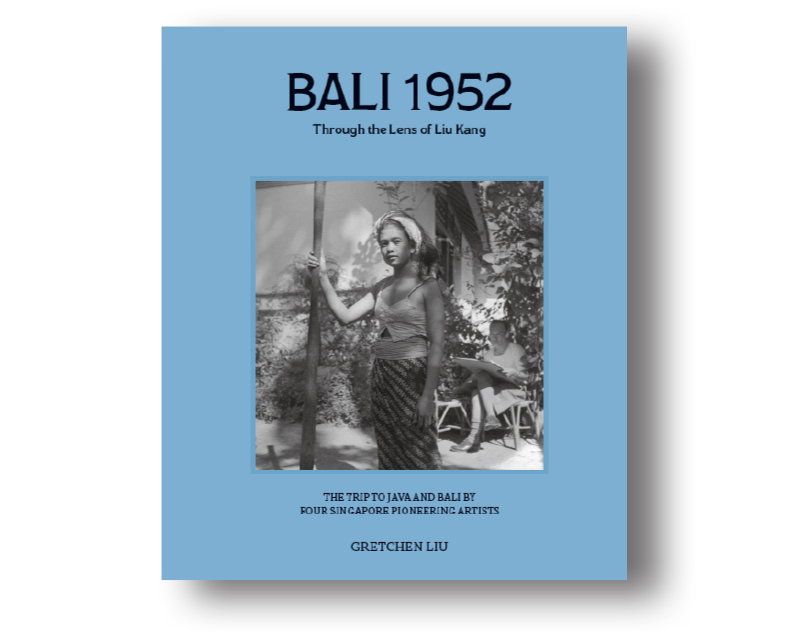

Note: This article is adapted from the preface of Bali 1952: Through the Lens of Liu Kang: The Trip to Java and Bali by Four Singapore Pioneering Artists.

Bali 1952: Through the Lens of Liu Kang chronicles the 1952 sketching adventure to Java and Bali by four artists – Chen Wen Hsi, Chen Chong Swee, Cheong Soo Pieng and Liu Kang. It features a selection of the photographs that Liu Kang took during the seven-week trip, from 8 June to 28 July. Forgotten for decades, they were unearthed in 2016 together with a diary he kept during the first half of the trip and nine letters written home.

My father-in-law, Liu Kang (1911–2004), was one of a small group of China-born, Shanghai-trained artists who settled in Singapore before and after World War II and animated the nascent art scene with a desire to portray their new homeland in art that showed its tropical character. Like many others who are eventually bitten by the family history bug, I regret that I did not learn more about his early life when he was around to answer questions. I never did ask him about the 1952 trip to Bali. In 2011, I was inspired to begin piecing together the details of his artistic journey when I saw the display of archival materials borrowed from the family for the exhibition Liu Kang: A Centennial Celebration, which marked the centenary of his birth and commemorated the donation of over 1,000 artworks to the National Heritage Board.1

I was initially curious about Liu Kang’s time in Shanghai, which coincided with a time of enormous social and cultural change in China. The cosmopolitan port city was then known as the “Paris of the East” and the vestiges of the past are still visible today. As I walked through the former French Concession, with its elegant tree-lined sidewalks and largely intact early 20th-century architecture, it was easy to think of him striding down the very same streets. Could I retrace his footsteps? Where had he taught? Who were his friends? How had his life intersected with other artists of the period?

Over the next few years and numerous visits to Shanghai, I pieced together the arc of his early life: art studies at Shanghai’s two influential art schools, the Shanghai Art Academy and the Xinhua Art Academy, in the 1920s; his journey from Shanghai’s French Concession to Paris for further art education, 1929–32; a teaching stint at the Shanghai Art Academy, 1933–37; his sudden departure from Shanghai at the start of the Second Sino-Japanese War in August 1937; his efforts to survive the Japanese Occupation, 1942–45; and finally his post-World War II art activities in Singapore, including his leadership roles in art societies.

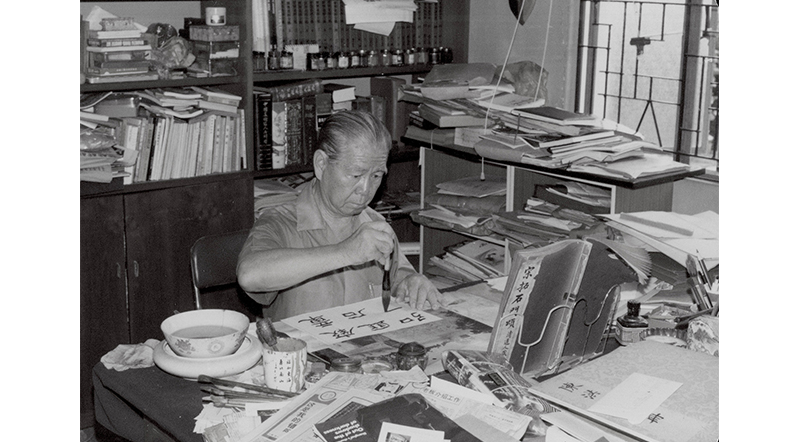

After his death in 2004, Liu Kang’s studio-study in the family home at 20 Jalan Sedap was tidied up and left essentially untouched. In 2016, the family finally faced the challenging question of what to do with the contents of the spacious room. Cognisant of its historical value, the family reached out to the National Library Singapore. The task of sorting through the large collection of books and memorabilia of a lifetime commenced in June 2017.

Over the next three months, a small team of library staff made 19 visits to the house. The joint effort included my sister-in-law, Liu Tow Sen. We worked our way through the books, letters, documents and certificates, catalogues and clippings, photographs and negatives, travel memorabilia and ephemera. Items set aside for donation were recorded. That September, 54 boxes were packed and taken away to the National Library. The bulk of the materials donated then are from the 1940s onwards and relate to Liu Kang’s years in Singapore.

Over those three months, I gained a deeper understanding of my father-in-law. He was a serious bibliophile who amassed a large collection of art and travel tomes in English and Chinese. Among his books on Bali is the classic Island of Bali by Miguel Covarrubias, a UK edition published in 1937 and purchased from City Book Store in Collyer Quay that he signed and dated 1949. He was an avid amateur photographer from an early age: we found negatives dating back to the mid-1920s.

I marvelled at the extensive paper trail left behind, especially the letters both received and written home, that survived the test of time, including those penned during the 1952 trip. Liu Kang, it seems, had a strong sense of history. The dislocations that affected the lives of many of his generation may have enhanced his instinct to keep and preserve. He may have intuited that one day the art world he inhabited would be of interest not only to Singapore art historians but also scholars of modern China.

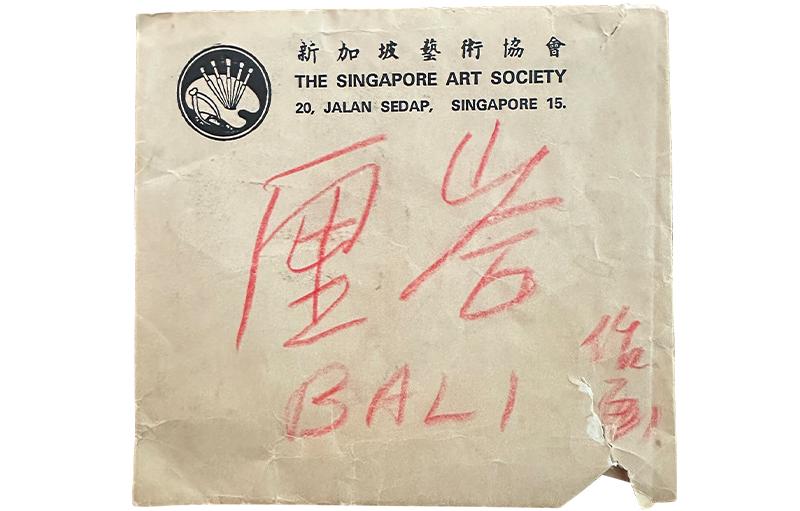

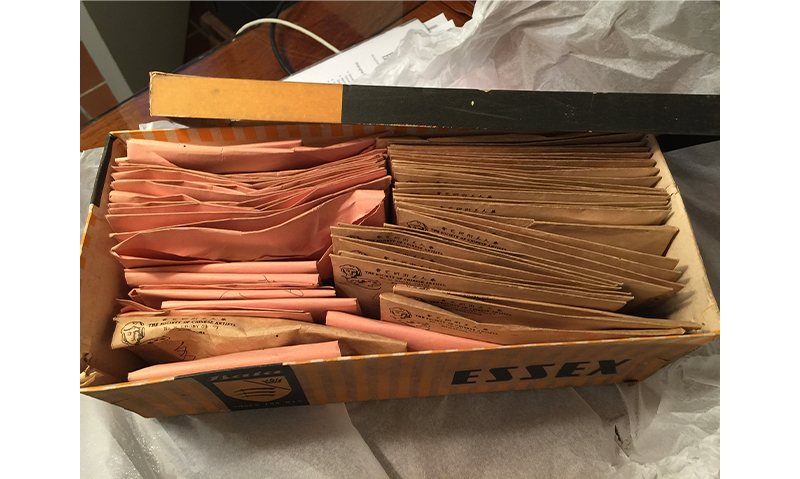

One afternoon in March 2016, I visited the study to do a preliminary investigation, opening drawers and cupboards at random. At the back of one of the cabinets, I saw a flash of colour that turned out to be a faded Bata shoebox. I pulled it out and carefully lifted the fragile lid. Inside were neat rows of brown and pink envelopes. Each envelope was labelled in a mixture of English and Chinese. The brown envelopes contained 6 cm × 6 cm negatives, and the pink envelopes turned out to have matching sets of prints the same size. I pulled out a few of the prints and realised they were scenes of Bali. I closed the lid and brought the box home. Four years later, during the Covid lockdown, I opened the box again and started to count: Liu Kang had taken an astonishing 1,000 photographs during the trip. The high-resolution scans of the negatives form the basis of this book and the exhibition that it accompanies.

The photos were taken with a Rolleiflex f/3.5, serial number 1226955. The camera is held at the waist with the viewfinder mounted on top. The receipt for the camera, also found, revealed that it was a last-minute acquisition – purchased on 7 June 1952, the day before the artists’ departure, from Wah Heng & Company, the well-known photo supply store at 95 North Bridge Road, for $522.75. Each roll of black-and-white film produced 12 exposures. Liu Kang developed the film and had the contact prints made as he travelled through Java and Bali. Alas, the fate of the camera is unknown. While a Rolleiflex camera was found in his study, it was a model from the early 1960s according to its serial number.

Chen Chong Swee and Cheong Soo Pieng also carried cameras. A skilled photographer, Chen Chong Swee favoured Leicas, according to his son Chen Chi Sing. During the trip, he shot on 35 mm black-and-white film and also developed his film along the way.2

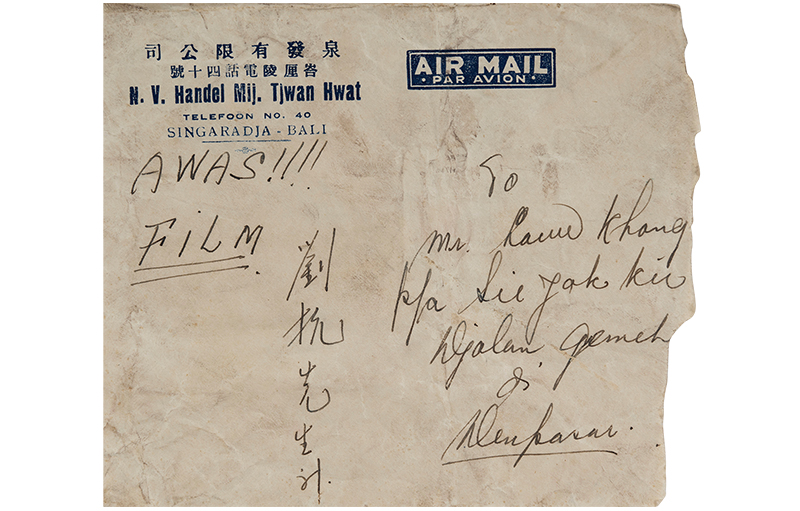

Unfortunately, Chen Chong Swee had a devastating experience when four rolls of film were ruined by a Bali photo studio. “But I am exceedingly exasperated by one irrecoverable loss,” he lamented in a letter to his wife. “There are so many wonderful images lost – there can never be another opportunity to capture them again. I can never get those photos back. For the pictures snapped from here on, I’m just going to take them all back and have them developed in Singapore.”3 The loss is significant: with 36 photos per roll, 144 images were gone forever. I am deeply grateful to Chi Sing for his support of this book. He generously shared the letters that his father wrote home as well as his father’s photographs and artworks.

It has not been possible to identify the camera used by Cheong Soo Pieng. According to his son Cheong Wai Chi, it was likely a Chinese brand. The artists exchanged photographs, and there are 16 in a specific format, 9 cm × 5.5 cm with a distinctive white deckle-edged border, including a group photo with Dutch painter Rudolf Bonnet in Ubud, that suggest they may have been taken by Cheong Soo Pieng. But other images in this format may instead have been purchased from a photo studio in Denpasar.

Mention must also be made of the fifth participant in the Bali portion of the field trip. Luo Ming can be seen also carrying a camera in Liu Kang’s photographs. A fellow Shanghai Art Academy alumnus, he began a lengthy journey through Southeast Asia in the late 1940s.4 Art school ties were rekindled when he visited Singapore in 1948. After a chance meeting with the artists in a Jakarta cafe, he decided to join their Bali sketching adventure. Luo Ming returned to China in 1954, and the fate of his photographs remains unknown.

Details of the trip come from several sources. First, Liu Kang’s diary, which was also found in his study and remains with the family. He purchased a steno notebook on his first day in Jakarta and recorded people met, places visited, amusing travel anecdotes and his private thoughts. The last entry is dated 29 June. Then there are the letters penned to wives – 11 extant from Chen Chong Swee to Tay Peck Koon, and nine from Liu Kang to Chen Jen Ping – which were reassuring, affectionate and informative.

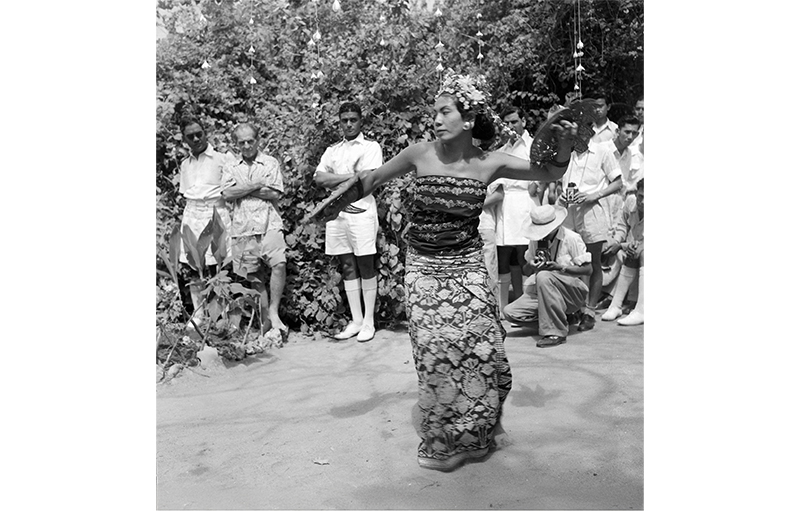

Eager to put minds at ease, both Chen Chong Swee and Liu Kang posted short letters on 9 June confirming their safe arrival in Jakarta. In subsequent letters one can sense the artists’ eagerness to share their experiences with those at home – comments on hotels (the good, the bad, the amusing), restaurants and meals (the unusual, the delicious), shopping (many visits to bookstores to purchase art supplies) and transportation (car, train and small boat, comfortable and chaotic). The travellers also inquired about children and revealed a tinge of homesickness. Of interest to art historians are hitherto unknown details of two life drawing residencies in Bali, the first near Denpasar and the second in Ubud.

The voices of the artists are gathered from other sources. All four artists wrote or spoke about the trip and its impact on them, but some more than others. Chen Wen Hsi and Liu Kang shared memories in their oral history interviews, recorded by the Oral History Centre in the early 1980s. The first language of the four artists was their Chinese dialect, and then Mandarin. Liu Kang was also fluent in French and could read and speak some English. (His extensive library consisted mainly of books in English.) It is fair to assume that the artists, living in a British colonial society, were exposed to periodicals, especially pictorial ones, in languages other than Chinese.

As I pieced together the story of the trip, I felt an irresistible urge to see whether it was possible to connect photographs with the art that was created during the trip or shortly after, hence the inclusion of works, mostly sketches and drawings and also some oil paintings, so that others may now explore the relationships discovered. I am grateful to the staff of the National Gallery Singapore and NUS Museum, Chen Chi Sing and the private collectors who assisted with this quest.

The photographs in the book appear as Liu Kang framed them. After 70 years, the negatives were in reasonably good condition. However, inevitably after prolonged storage in a warm and humid environment, there were some instances of fading, discolouration and staining that resulted in tonal shifts, and some diminished image density. The digital restoration process involved adjustments to exposure settings, tonal density and the application of digital retouching and enhancement techniques tailored to the specific characteristics of the negatives.

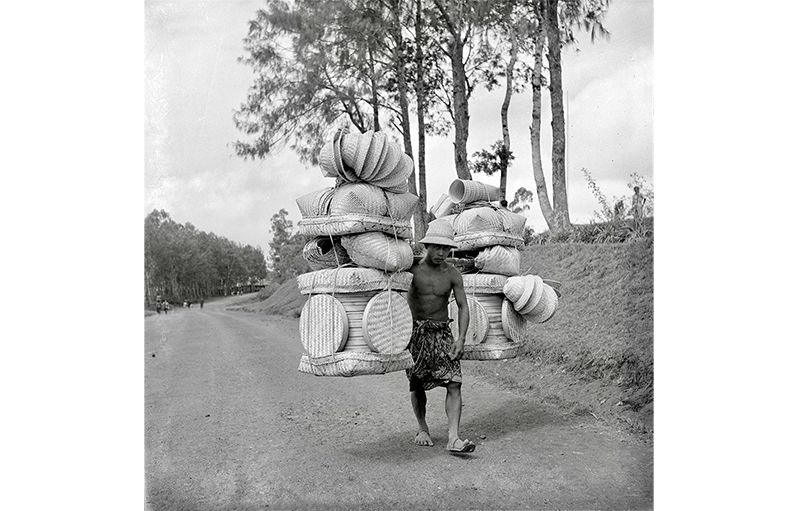

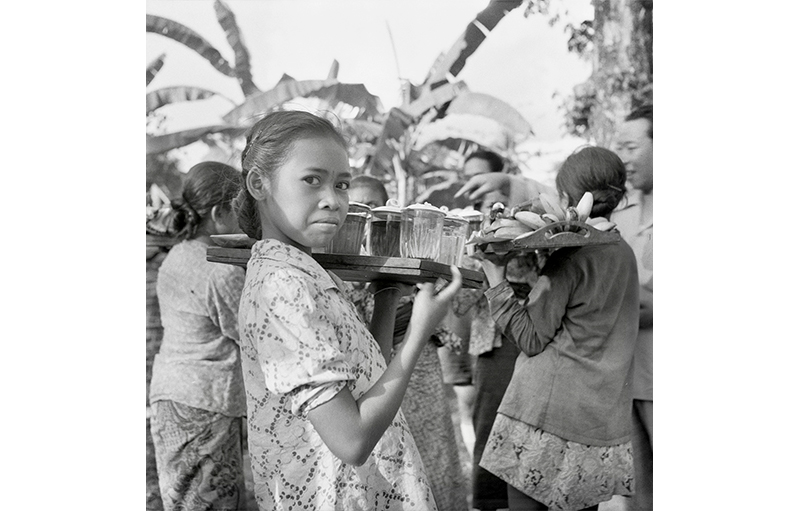

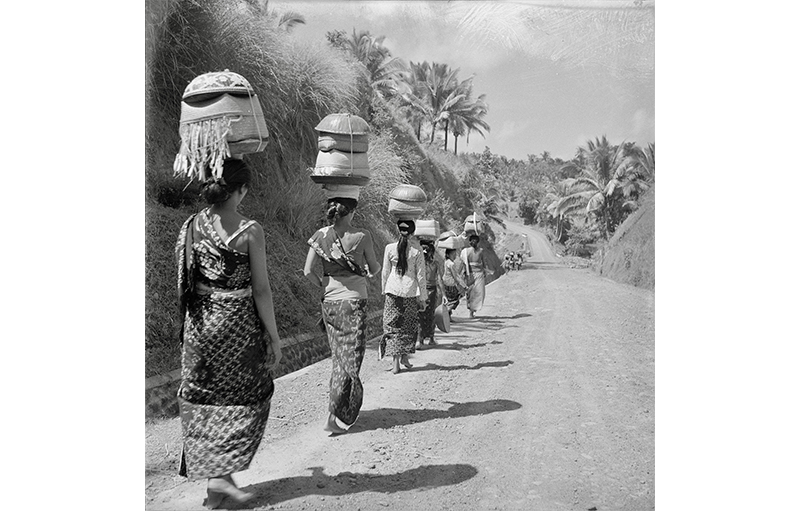

Liu Kang focused his lens on landscape, architecture and scenes of daily life, a combination of documentation, art and street photography – the chance encounters, random incidents and candid scenes that capture a moment in time. In this way, the photographs offer not only a comprehensive record of the field trip, but also a snapshot of a particular moment in Indonesian history. While we will never know why he took so many photographs (for pleasure? to publish?), the forgotten photographs can at last be seen. As to what light they may shed on the larger story of Singapore’s art history, that is for others to discuss and debate.

Gretchen Liu’s Bali 1952: Through the Lens of Liu Kang: The Trip to Java and Bali by Four Singapore Pioneering Artists was published in conjunction with the exhibition, Untold Stories: Four Singapore Artists’ Quest for Inspiration in Bali 1952, held at Level 10 of the National Library Building from 14 February to 3 August 2025. The book is available for reference at the Lee Kong Chian Reference Library (call no. RSING 779.995986 LIU), for loan at selected public libraries (call no. SING 779.995986 LIU), and for sale at physical and online bookstores.

Gretchen Liu is a former journalist, writer and an independent scholar with an interest in visual culture and heritage. She is the editor and author of several books. Most recently she has been researching the early life of her father-in-law Liu Kang, a journey that has taken her deep into early 20th-century Chinese art history.

Gretchen Liu is a former journalist, writer and an independent scholar with an interest in visual culture and heritage. She is the editor and author of several books. Most recently she has been researching the early life of her father-in-law Liu Kang, a journey that has taken her deep into early 20th-century Chinese art history.NOTES

-

Yeo Wei Wei, ed., Liu Kang: Colourful Modernist (Singapore: The National Art Gallery Singapore, 2011). (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 759.95957 LIU). The book was published in conjunction with the exhibition Liu Kang: A Centennial Celebration organised by the National Art Gallery, supported by the National Heritage Board and presented at the Singapore Art Museum, 29 July–16 October 2011. ↩

-

Chen Chi Sing has two of his father’s cameras, a Rolleiflex and a Leica M3, a 35 mm rangefinder released in 1954. The camera used during the Bali trip was likely the precursor to the Leica M3. ↩

-

Chen Chong Swee, letter to his wife (Tay Peck Koon), 5 July 1952. Translated from the original letter digitised by National Gallery Singapore Library & Archive with kind permission from Chen Chi Sing. Some of Chen Chong Swee’s Java and Bali photographs were featured in the book by Phua Chay Long 潘醒农,《东南亚名胜》[Celebrated places in Southeast Asia] (Singapore: Nantao Publishing House, 1954). (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 959 PCL) ↩

-

Luo Ming was the other participant of the Bali sketching trip. He was a graduate of the Shanghai Art Academy in Western painting. In 1947, he left Hong Kong, where he taught, and travelled to Thailand, Malaya, Singapore, Hong Kong and Indonesia, painting and holding solo exhibitions. In 1948, he spent several months in Singapore and held an exhibition of his art that year, which was was sponsored by the Society of Chinese Artists. See “Art Display Is Planned,” Singapore Free Press, “Huajia Luo Ming shi bu ri fanguo” 画家罗铭氏不日返国 [Painter Luo Ming will return to China soon], 南洋商报 Nanyang Siang Pau, 16 August 1948, 6 (From NewspaperSG) ↩