Mazu Worship in Singapore

Mazu devotion, which first came to Singapore in 1810, lives on in its traditions and processions.

By Alvin Tan

Amidst a sea of outstretched arms wielding mobile phones, selfie sticks, the odd camera and smouldering joss sticks, her throng of devotees surged forward as the procession began at about 7 pm, under steadily darkening and increasingly overcast skies that threatened to break anytime. It was all a very fitting backdrop for Mazu (妈祖) – Goddess of the sea, and of the wind and rain – as she began her procession from Thian Hock Keng temple (天福宮) on 1 May 2024 (or the 23rd day of the third lunar month). Last held in 2019, the Excursion of Peace was the climax of almost a week of festivities that had begun three days earlier, on 28 April 2024.

From Local Deity to Empress of Heaven

As in the case of many Chinese deities, Mazu – also known as Lin Moniang (林默娘) – was a historical personage who was first recognised as a deity by the people of Meizhou island, Putian, in Fujian province during the late 10th century.1 Born in 960, she was later given the name mo (默; silent) as she did not cry from the time she was born till the end of her first month.2 Legend has it that Mazu’s birth “was attended to by auspicious portents. She was an exceptionally pious girl, and at age of 13 she met a Taoist master who presented her with certain charms and other secret lore. When she was 16, she manifested her magic power by saving the lives of her father and elder brother, whose boat had capsized.3 The name niang (娘; young lady) was accorded as a mark of respect several hundred years after her death in 987.4

Devotion to Mazu began in the Song dynasty (960–1270). To “all who must hazard their lives upon the waters”, Mazu was regarded as the most important deity.5 As early as 1288, Mazu temples were found in all the maritime provinces of coastal China.6 Four hundred years later, the Ming dynasty (1368–1644) co-opted her into the official pantheon of deities overseen by the Board of Rites in the imperial court.7

Mazu is best known by her appellation, Tian Hou (天后; Empress of Heaven), conferred in 1737 during the Qing Dynasty (1644–1911) by Emperor Gaozong. In rank and status, she is equal to all male deities with the exception of the Emperor of Heaven.8 These efforts to elevate her into the official pantheon of deities reflected her widespread popularity.

Given that Mazu’s realm is the sea, it is unsurprising a maritime-centred mythology has been built around her. In China’s history, the most significant maritime voyages took place from 1403 to 1433 during the Ming dynasty. Helmed by Admiral Zheng He, the voyages went as far as India and littoral East Africa. Mazu was venerated onboard Zheng He’s ships, with daily prayer and incense offerings for thanksgiving and to petition for protection and assistance. These must have been heeded for Mazu’s intervention miraculously saved the fleet from shipwreck during its fifth voyage.9

Mazu is often portrayed clothed in “a gown with embroidery work and a crown with glass beads”, and clasping an imperial tablet in both hands. She is flanked by two deities, Shunfeng’er (顺风耳; Favourable-Wind Ear) and Qianliyan (千里眼; Thousand-Li Eye), who are respectively all-hearing and all-seeing, and serve as her bodyguards and aides.10 It must be noted that both attributes were indispensable to sailors in an era when modern navigational aids did not exist.

Building Thian Hock Keng

Mazu’s history in Singapore is tied closely to the history of Chinese immigrants here. According to some accounts, Mazu worship predated Stamford Raffles’ arrival in Singapore. As early as 1810, Chinese immigrants were working on the island’s pepper and gambier plantations and they brought Mazu with them. Eventually, a small joss house was built along the waterfront to worship her.11

Later Chinese immigrants, who came from coastal provinces in southern China, continued this devotion as they travelled on junks with Mazu altars onboard. Arriving in Singapore after a long, hazardous voyage, they naturally made their way to the humble joss house located along the waterfront to give thanks for a safe voyage.12

Mazu devotion transcended dialect lines, reflecting the widespread devotion to her in southern China. In 1820, the Teochews set up Yueh Hai Ching Temple (粤海清庙) on Phillip Street to venerate her. And in 1857, the Hainanese built Kheng Chiu Tin Hou Kong (琼州天后宫) along Malabar Street.13 At the same time, Mazu was also worshipped by those who engaged in activities related to the sea such as charcoal traders, motorboat owners and fishermen.14

As the port of Singapore grew and fortunes were made, prominent businessmen provided the impetus to build temples dedicated to Mazu as a form of thanksgiving. In the Hokkien community, the businessman and philanthropist Tan Tock Seng led these efforts to build what became the Thian Hock Keng temple (to replace the joss house). In 1838, he effected a series of land purchases for this purpose and donated 3,074 Spanish dollars to the building. Construction began the following year, and the temple was eventually completed in 1840 to the tune of 37,000 Spanish dollars.

All the building materials were imported from China. The following year, a Mazu statue from Meizhou island arrived in Singapore and a magnificent procession was mounted afterwards in her honour.15

In Thian Hock Keng, Mazu occupies the main (or central) hall. Guan Gong (关公; God of War) sits on her left and Baosheng Dadi (保生大帝; His Majesty the Protector of Life) on her right. In the rear hall sits Guanyin (观音; Goddess of Mercy). The reasons for devotion to Mazu are vividly captured in a pair of commemorative steles put up in 1850:

We, the tangren (Chinese), have come from the interior by junks to engage in business here. We depended on Holy Mother of Gods to guide us across the sea safely and we were able to settle down here happily. Things are abundant and the people are healthy. We, the tangren, wish to return good for kindness. So we met and decided to build a temple in the south of Singapore at Telok Ayer to worship the Heavenly Consort day and night.16

Mazu Devotion in Singapore

Even as Singapore rapidly developed, Mazu devotion stayed relevant and popular. Throughout the latter half of the 20th century, the press, especially the Chinese newspapers, ran articles about Mazu and Thian Hock Keng on or around her birthday. A network of 21 Mazu temples and associations, tended to by different dialect and surname groups, still remain active in Singapore today.17 Despite Singapore’s modernisation, there remained a healthy interest in traditional religious practices, which gradually evolved to take on significance beyond the spiritual.

For instance, on Mazu’s birthday on 25 April 1954, the Nanyang Siang Pau newspaper ran an article about Mazu-related organisations in Singapore that reflected the extent of popular devotion. At the New Era Restaurant, reportedly 180 tables (with 1,800 seats) were booked for this date. All across Singapore, Mazu societies held celebrations.18

Mazu worship remains common in Singapore today, for different reasons and in different forms. Nelson Lim, 60, chairman of the Culture and Heritage Committee at the Singapore Hokkien Huay Kuan, recalls visiting the temple as a child to worship Mazu. Growing up in the Kallang River area, where many depended on marine-related trades for a living, Mazu worship was common. Lim noted, however, that devotion to Mazu has evolved from asking for favours to being a form of cultural expression and perpetuation of Chinese heritage and history.19

To 55-year-old Dr Koh Chin Yee, vice-chair of Thian Hock Keng’s temple management committee, Mazu signifies and embodies benevolence, justice, peace and valour and these values, together with Singapore’s immigrant history, formed the narrative of his livestream of the Mazu birthday procession on 1 May 2024. Belief in Mazu formed an important part and played a critical role in the early migrant Chinese community, across all major dialect groups. For instance, the Singapore Hokkien Huay Kuan, established in 1840 on the grounds of Thian Hock Keng, founded schools like Tao Nan and Ai Tong which still exist today, he noted.20

Mazu worship provides quantity surveyor Yvinne Neo, 45, with spiritual sustenance and comfort. However, the element of giving back is also important. “By participating in volunteer activities and charity events in the temple (such as providing free Mazu noodles, mung bean soup, rice noodles to the public and charity banquets for poor elderly people), individuals can also give back to society and practise the concept of doing good in the Mazu belief,” said Neo, who is also a temple volunteer.21

Worshipping Mazu at the temple itself is an important part of the experience. When asked whether he worships Mazu at home, a 52-year-old software engineer who only wanted to be known as Mark, explained that with the rituals, observations and obligations that a home altar entails, it would be difficult for him as a working professional to keep up.22

Mazu’s Birthday Celebrations

In 1840, Mazu’s first birthday procession was held – which cost a princely 6,000 Spanish dollars – to mark her arrival in Singapore. The Singapore Free Press reported that the procession “dragged its length along” to the extent of nearly the third of a mile, to the usual accompaniment of delectable gongs, and with gaudy banners of every colour, form and dimension “floating the pale blue sky”. The paper further noted that “the Divinity [Mazu] herself was conveyed in a very elegant canopied chair, or palaqueen [sic], of yellow silk and crape [sic], and was surrounded by a body guard of celestials, wearing tunics of the same colour”. “She is supposed to be the especial protectress of those who navigate the deep – at least, it is to her shrine that Chinese sailors pay the most adoration… The procession, we are informed, is regarded as a formal announcement to the Chinese of her advent in this settlement.”23

This event was frowned upon by Protestant missionaries, who distributed a tract to disprove why Mazu is not as powerful or superior a deity as the Chinese painted her out to be.24 Regardless, processions took place once every three years until 1926.25

Almost 90 years would elapse until the procession was revived in 2016.26 And whether it takes place or not is not decided by bureaucratic fiat. Rather, obtaining Mazu’s consent first-hand is of paramount importance for the sacred to enter into the realm of the profane.27 To do so, the temple uses divination lots, traditionally two crescent-shaped pieces of red painted wood that are flat on one side and concave on the obverse, to seek her views on the matter. With Mazu’s approval, the first procession in almost a hundred years was held in 2016, and then annually until 2019. Social distancing measures during the Covid-19 pandemic meant that the procession in 2024 was the first to take place in five years.28 (In 2025, the procession will take place on 20 April.)

Arriving at the temple at about 6:30 pm on 1 May 2024, I was greeted by the festivities, which were well underway. A week prior to her birthday, Thian Hock Keng’s social media team began posting on its Facebook page, publicising details about the celebrations – devotional items, fringe events and the birthday process.

Mazu’s birthday procession – dubbed the Excursion for Peace – was a meticulously planned and executed event. Unlike similar processions in Taiwan which are not tied to a fixed route – it was left to Mazu to decide where she wanted to go and for the statue bearers to discern – Singapore’s procession was thoroughly scripted and planned from beginning to end.29

Around 7 pm, the elements comprising the Excursion for Peace contingent got into place. Performances by lion and dragon dances, accompanied by big-headed dolls, sent Mazu off on her tour of the realm. Leading the way, at the head of the contingent, was a horizontal cloth banner embroidered with Mazu’s title, 天上圣母 (Holy Heavenly Mother), which was flanked by a pair of lanterns at both ends. Behind the lanterns, running down the flanks of the contingent, was a single row of twin phoenix flags also bearing Mazu’s title – the phoenix is a symbol of the feminine – held aloft by male devotees.

Following close behind was Mazu’s immediate entourage. Heavenly generals, flanked by the signs “Silence” (肃静) and “Retreat” (回避), put everyone, spirit or human, on notice. This was followed by the Lead Flag. All these made up the beginning of the sanctum, where Mazu held court. To add to the martial air, a set of 12 weapons borne by devotees escorted and protected her. This was an occasion of pomp and splendour – the Empress of Heaven was out inspecting her realm. Next up were the ritual elements made up of Taoist priests, accompanied by the principal and lead devotees.

In the inner sanctum, a parasol, kept spinning continuously by a group of male devotees, provides shade and cover for Mazu. Devotees believe that she is physically here. Accompanied by her guardian deities – Shunfeng’er and Qianliyan – Mazu sits on a red, swinging sedan chair studded with red LED light strips and borne by a party of male devotees from the Boon San Lian Ngee Association. Mounted on the sedan chair, just behind her, is a set of flags of five colours signifying the five elements of metal, wood, water, fire and earth. They are symbols of her authority over her generals and troops. These also remind devotees and wandering spirits of her high status. A pair of fans decorated with sun and moon motifs flank the sedan chair, protecting her and the throng of around one thousand devotees following closely behind.30

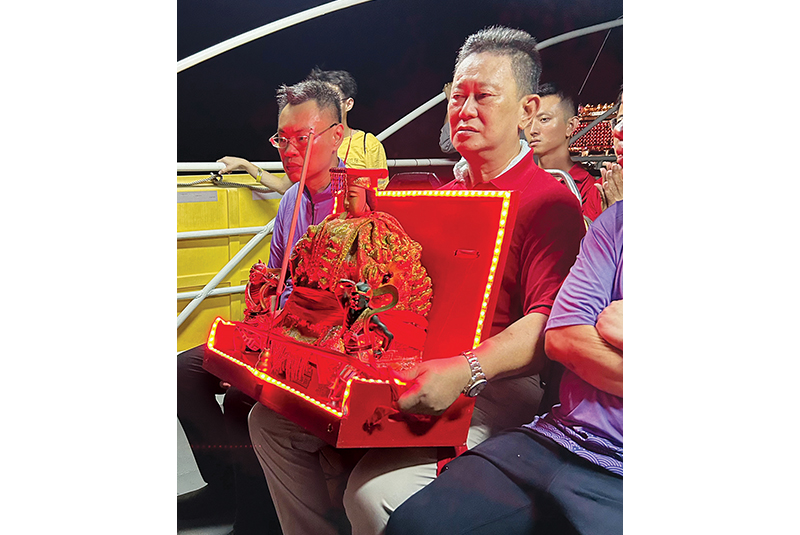

The procession route snakes its way through the Central Business District. From Thian Hock Keng on Telok Ayer Street, the contingent proceeds on foot to Siang Cho Keong Temple (仙祖宫) on Amoy Street, where it pauses to exchange incense as a mark of respect and acknowledgement of the temple’s resident deity – Dabogong (大伯公; God of Prosperity). Mazu is then carefully and reverently transferred from her mount on the sedan chair to the open-air upper deck of a double-decker bus for the next leg of her excursion: to Boon San Lian Ngee Association at Hong Lim for another exchange of incense.

Then it is onwards to Marina South Pier via Pickering Street, Church Street, Collyer Quay and Marina Boulevard. Riding at the front of the bus, which is typically crowded with tourists and day trippers, Mazu surveys and blesses her realm impassively as her entourage drives past hypermodern skyscrapers that characterise Singapore’s new downtown.

A lion and dragon dance greets Mazu as she arrives at Marina Bay Cruise Centre. For her, going down the narrow and curved stairs of the bus is no easy feat. She is carefully, almost gingerly, transferred from the hands of one attentive principal devotee to another. Smoke from the incense fills the stairway. There is a little pause at the ferry boarding point in Marina Bay Cruise Centre. Mazu is delayed briefly as a uniformed Immigrant and Checkpoints Authority officer unlocks and opens the access door for her. When a sacred deity enters the profane and quotidian in her material form, she finds herself subject to its rules and regulations.

From here, it is a pleasant and cool 45-minute cruise out to the waters around the Southern Islands and back. Mazu is in her element as Goddess of the Sea as she looks over the container ships, oil tankers and other marine vessels in Singapore’s Eastern Anchorage from her vantage point on the open top deck of the ferry.31

For her devotees, it is time to unwind a little from the noise and hustle and bustle of the event. Some ask to take selfies with Mazu. Groups of devotees, with mobile phones in outstretched arm, snap happy photos with Mazu, which make their way onto social media and to friends and family on Whatsapp almost instantaneously. On the Starboard side, Dr Koh Chin Yee – who is also vice-chair of the cultural committee of the Singapore Hokkien Huay Kuan – livestreams the event, providing an engaging narrative about Singapore’s skyline and history. As with so many aspects of Singaporean life, tradition and modernity appear to be totally at ease with each other here. Mazu, broken down into bits and bytes, ones and zeroes, finds herself streamed across the realms of the internet and reaching, unsurprisingly, a global audience.32

A throng of devotees presses up against the bus as Mazu returns to Telok Ayer. The procession makes it way down Stanley Street, passes through the Singapore Hokkien Huay Kuan building where it comes to a halt in front of the getai stage at the forecourt of the building. As Mazu ends her inspection tour and returns to Thian Hock Keng, her devotees cross a Bridge of Blessings in turn. A stamp is affixed on their clothing, signifying the imparting of Mazu’s blessings and good wishes on them.

Mazu Worship Lives On

In 1840, Mazu’s birthday procession drew (caustic) comments from the European population and even missionaries chimed in on it.33 In 2024, the procession is no longer presented solely as a religious event but also as a cultural experience, a celebration of heritage and expression of tradition.

The birthday procession was not the only time that Mazu undertook a journey in 2024. In April, as Senoko Fishery Port wound up its operations, its tenants – mainly fish merchants and their workers – were moved to Jurong Fishery Port. An altar of Mazu moved with them. “In the past, the fishermen would come to the Mazu altar near the jetty to pray for safety in the seas and a good catch,” said 72-year-old fish merchant Phillip Yap. “This is a tradition from the old Kangkar village in Punggol and then to here, so we appealed to bring it to Jurong Fishery Port,” he added.34

So long as Singapore’s economic story continues to be intertwined with the sea, Mazu worship and culture will continue to endure, whether as religious devotion, cultural expression or heritage experience.

Alvin Tan is an independent researcher and writer focusing on Singapore history, heritage and society. He is the author of Singapore: A Very Short History – From Temasek to Tomorrow (Talisman Publishing, 2nd edition, 2022) and the editor of Singapore at Random: Magic, Myths and Milestones (Talisman Publishing, 2021).

NOTES

-

James L. Watson, “Standardising the Gods: The Promotion of T’ien Hou (“Empress of Heaven”) Along the South China Coast (960 – 1960),” in Popular Culture in Late Imperial China, ed. David Johnson, Andrew J. Nathan and Evelyn S. Rawski (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1985), 295. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RCLOS 951.03 POP-[GH]) ↩

-

Li Lulu李露露, Mazu xinyang 妈祖信仰 [Mazu belief] (北京: 学苑出版社, 1995), 12. ↩

-

Laurence Thomson, Chinese Religion: An Introduction (Belmont: Dickensen Publishing Inc., 1969), 57. ↩

-

Li, Mazu xinyang, 12. ↩

-

Thomson, Chinese Religion, 57. ↩

-

Irwin Lee, “Divinity and Salvation: The Great Goddesses of China,” Asian Folklore Studies 49, no. 1 (1990): 63. (From JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website) ↩

-

Watson, “Standardising the Gods,” 293–94, 299–300. ↩

-

Lee, “Divinity and Salvation,” 63; “Mazu de laojia” 妈祖的老家 [Mazu’s hometown], 联合晚报 Lianhe Wanbao, 3 November 1987, 10. (From NewspaperSG). In total, 22 titles were conferred upon her from the Song dynasty to the Qing dynasty. See “Qian zai jie bao feng” 千载皆褒封 [Praise for thousands of years] 联合晚报 Lianhe Wanbao, 3 November 1987, 10. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Barbara Watson Andaya, “Seas, Oceans and Cosmologies in Southeast Asia,” Journal of Southeast Asian Studies 48, no. 3 (October 2017): 362. (From JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website) ↩

-

Evelyn Lip, Chinese Temples and Deities (Singapore: Times Books International, 1986), 31. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RCLOS 726.1951095957 LIP); Li, Mazu Xinyang, 27. ↩

-

“Cong tianhou dan shuo dao mazu gong” 從天后誕說到媽祖宮 [From Tianhou’s birthday to Mazu palace], 南洋商报 Nanyang Siang Pau, 5 May 1970, 8. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Guseguxiang de tianfu gong” 古色古香的天福宮 [The antique Thian Hock Temple], 星洲日报 Sin Chew Jit Poh, 7 June 1973, 20; “Xing zhou mazu gong yu mazu” 星洲媽祖宮與媽祖 [Xingzhou Mazu palace and Mazu], 南洋商报 Nanyang Siang Pau, 30 October 1955, 4. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Cheng Lim Keak, “Traditional Religious Beliefs, Emigration and the Social Structure of the Chinese in Singapore,” in A General History of the Chinese in Singapore, ed. Kwa Chong Guan and Kua Bak Lim (Singapore: World Scientific Publishing, 2019), 496. ↩

-

“Mazu yu xinjiapo” 妈祖与新加坡 [Mazu and Singapore], 联合早报 Lianhe Zaobao, 17 March 1991, 38. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Chendusheng jiazu lingdao fujian huiguan 75 nian” 陈笃生家族领导福建会馆75年 [Tan Tock Seng’s family leads Hokkien Huay Kuan for 75 years], 联合早报 Lianhe Zaobao, 7 April 1991, 38. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Hue, “Chinese Temples and the Transnational Networks,” 503. ↩

-

Hue, “Chinese Temples and the Transnational Networks,” 504; See also “Mazu” 妈祖 [Mazu], 联合早报 Lianhe Zaobao, 20 December 1990, 8. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Tianhou dan yu tianhou hui de zuzhi” 天后诞与天后会的组织 [The organisation of the Queen’s Day and the Queen’s Association], 南洋商报 Nanyang Siang Pau, 25 April 1954, 6. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Nelson Lim, interview via Zoom, 3 July 2024. ↩

-

Dr Koh Chin Yee, email interview, 1 July 2024. ↩

-

Yvinne Neo, email interview, 18 June 2024. ↩

-

Mark, correspondence via Whatsapp, 30 June 2024. ↩

-

“Chinese Processions,” Singapore Free Press, 23 April 1840, 3. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Mazu po shengri zhi lun” 妈祖婆生日之论 [On Mazu’s birthday], 南洋商报 Nanyang Siang Pau, 25 October 1982, 31. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Collaterals from Thian Hock Keng mention that such excursions should either be held for three consecutive years or every three years. ↩

-

Collaterals from Thian Hock Keng. ↩

-

Émile Durkheim, The Elementary Forms of Religious Life (Oxford & New York: Oxford University Press, 2008), 36– 37, 228–29. [NLB has the 1995 edition published by The Free Press, call no. 306.6 DUR.] ↩

-

Collaterals from Thian Hock Keng. ↩

-

“Noisy, Gaudy and Spiritual: Young Pilgrims Embrace an Ancient Goddess,” New York Times, 3 May 2024, https://www.nytimes.com/2024/05/03/world/asia/taiwan-religion-mazu-pilgrimage.html. ↩

-

“Mazu rao jing xun an yu 6000 xinzhong tianfu gong qifu” 妈祖绕境巡安 逾6000信众天福宫祈福 [Mazu patrols the border and more than 6,000 believers pray at Tianfu Temple], 联合早报 Lianhe Zaobao, 1 May 2024, https://www.zaobao.com.sg/news/singapore/story20240501-3548512. ↩

-

Singapore Port Information,” Port Info Hub Pte. Ltd., accessed 11 February 2025, https://portinfohub.com/port-information/singapore/singapore-port-anchorages/. ↩

-

This is not unlikely given the global footprint of Mazu temples which extends as far as San Francisco in California and Austin in Texas, United States. ↩

-

“Tides of Change: One Last Look at Senoko Fishery Port,” Straits Times, 13 March 2024, https://www.straitstimes.com/multimedia/graphics/2024/03/senoko-fishery-port-singapore/index.html?shell. ↩