The Construction of Bali’s Mystique

In 1953, four pioneering Singapore artists held an exhibition of artworks arising from their travels to Bali the previous year. Their trip was inspired by an image of the island as an untouched Eden.

By Nadia Ramli and Goh Yu Mei

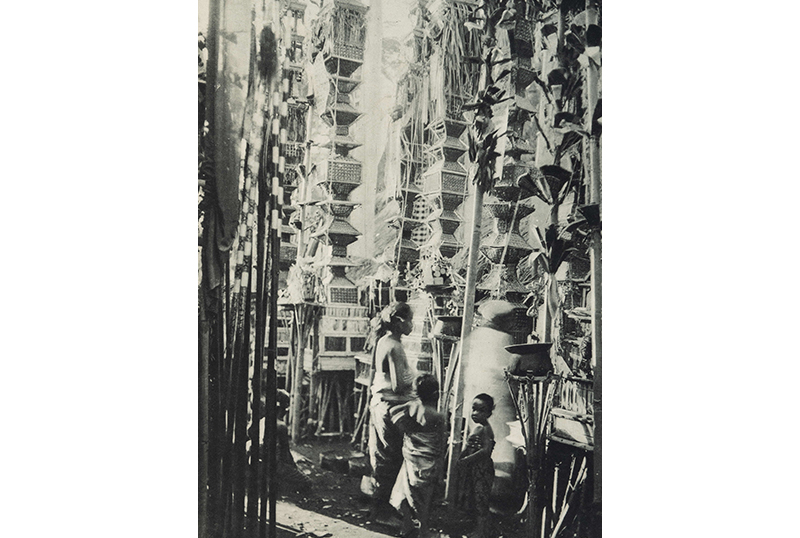

Mention Bali and the image that springs to mind is that of a paradise on earth, with its verdant hills, cascading rice terraces, pristine beaches, mesmerising dances and beautiful local women. This image, however, did not appear out of nowhere. Key to shaping popular imagination have been cultural products like books and films that use the island as a backdrop which, in turn, reinforce the image of Bali as a paradise. The 2010 biographical romantic drama Eat Pray Love – a movie starring Julia Roberts about a woman who searches for self-discovery as she journeys to Italy, India and Bali – is a well-known example of a movie that capitalises on Bali’s allure.1

The construction of Bali as a beautiful, mysterious and exotic destination is an effort that goes back to the early 20th century. An image initially constructed by colonial administrators who wanted to create a tourist destination eventually took on a life of its own as artists, writers, photographers, journalists and filmmakers descended on the island.

Among the artists who were influenced by this image of Bali and who, in turn, also helped to burnish this image in the region were four pioneering Singapore artists – Liu Kang, Chen Chong Swee, Chen Wen Hsi and Cheong Soo Pieng. In 1952, they embarked on a seven-week journey across Indonesia from 8 June to 28 July, culminating in Bali. Inspired by the island’s lush landscapes, rich culture and artistic traditions, the artists’ 1953 exhibition of paintings and sketches arising from this trip is considered a major milestone in Singapore’s art history.2

In his oral history interview, Liu Kang recalled: “We had an impression of the island of Bali from a long time ago because we regularly saw reports on Bali in books and illustrated magazines, especially those with pictures introducing Bali. [We] felt that Bali had incredible natural scenery, the attire their locals wore and their dances were all excellent subject matter for drawing.”3

The Hidden Side of Paradise

Bali’s reputation as an island paradise today emerged from a complex interplay of historical, political and sociocultural factors. Colonial narratives, coupled with the strategic promotion of the island as a tourist attraction, combined with the rise of leisure travel in the early 20th century made destinations in Southeast Asia such as Bali more accessible to Western travellers. These factors, together with the island’s unique cultural and physical landscape, created a captivating portrayal of Bali. However, the romanticised image of paradise often obscures the impact of colonisation on Bali and its people.

The first documented European contact with Bali was in 1597 when merchants from Amsterdam, led by Cornelis de Houtman, arrived on the island after a two-year journey. The Dutch fleet was reportedly impressed by the Balinese prosperity and hospitality, in contrast to the austere Islamic sultanates of Java.4 The trip was instrumental in opening up the East Indies and the Indonesian spice trade to the Dutch as well as the eventual formation of the Dutch East India Company in 1602.

In the 17th and 18th centuries, the growth and expansion of the Dutch East India Company laid the groundwork for deeper Western influence in the region. By the 19th century, the Dutch had asserted control over Bali through a series of military interventions, fuelled by pretexts like the Balinese practice of tawan karang, or the right to salvage shipwrecks. The Dutch final conquest of Bali in the early 20th century, marked by fierce battles and puputan (carrying out mass ritual suicides to avoid the humiliation of surrender), could be seen as symbolic of the local resistance against the brutality of colonisation.5

After the violent invasion of Bali, the Dutch colonial government sought to create a more “favourable” image with policies that aimed to, on the one hand preserve and protect the Indo-Javanese civilisation from modern influences and, on the other, promote tourism.6 This also tied in with the agenda by the Dutch to stifle political activity and contain the spread of nationalism in the rest of the archipelago.7

A Colonial Fantasy

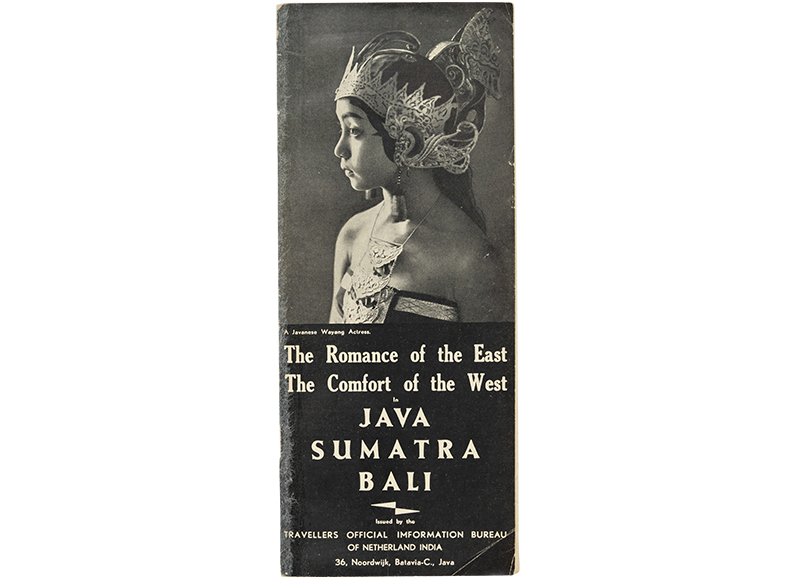

The Dutch developed infrastructure and promoted Bali as an exotic, untouched getaway, intertwining their economic and political ambitions with the island’s tourism.8 The establishment of the Association for Tourist Traffic in Netherlands India (“Netherlands India” refers to the Dutch East Indies, the colony of the Netherlands’ in Southeast Asia, primarily consisting of present-day Indonesia) marked an era of tourism efforts for the island, casting the Dutch East Indies as a coveted travel destination.9

By 1914, travel guides and brochures were promoting Bali as the “Gem of the Lesser Sunda Isles” and mythologising the archipelago with language like “Mystic Isles of Java, Sumatra and Bali” and “Romance of the East”.10 The 1928 inauguration of the Bali Hotel (present-day Inna Bali Heritage Hotel), the island’s first foray into “modern” hospitality, was orchestrated under the auspices of the Koninklijke Paketvaart Maatschappij (KPM; Royal Packet Navigation Company), a shipping line.11

The KPM and other shipping lines also sponsored a number of early tourist pamphlets and publications such as the journal, Sluyter’s Monthly, which was later renamed Inter-Ocean: A Netherlands East Indian Magazine Devoted to Malaysia and Australasia.12 These efforts, coupled with the introduction of regular steamship services between Java and Bali in the 1920s, facilitated the influx of visitors seeking their slice of paradise.

“Picture Perfect”

Bali’s allure was also fuelled by the artists, photographers and writers who descended on the island in search of inspiration. Depictions of the island, from canvases to celluloid, created a compelling narrative that resonated with Western fantasies of Bali as a paradise.13

The island often drew comparisons to French painter Paul Gaugin’s romantic image of Tahiti as an “untouched paradise”. Early European artists such as Wijnand Otto Jan Nieuwenkamp and Gregor Krause played a significant role in shaping the perception of Bali through their art. Nieuwenkamp, who was Dutch, was one of the first European artists to visit Bali. His illustrated albums and publication, Bali en Lombok (1906–10), introduced the island to a wider audience. Together with the German physician and photographer Gregor Krause, they advanced Bali’s appeal through the first exhibition of Balinese art in Amsterdam in 1918.14

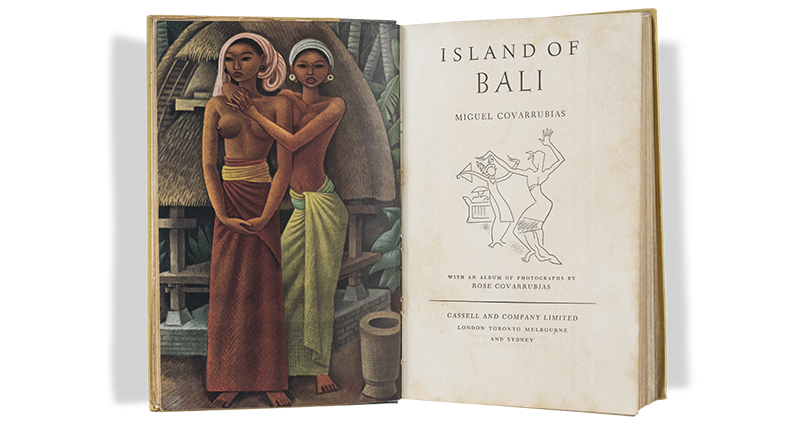

Krause’s 1920 publication, Bali 1912, paints a vivid portrait of Bali’s landscapes, people and customs. The book showcases a collection of nearly 400 photographs curated from thousands taken during his stint as a medical officer in Bangli, near Ubud, from 1912 to 1914.15 His lens captured an idyllic vision of indigenous life that would later inspire other artists and writers. The Mexican painter Miguel Covarrubias, German artist Walter Spies and Austrian novelist Vicki Baum were among those drawn to Bali’s shores, their subsequent works further contributing to the island’s reputation as a paradise.16

Drawn to Bali

Early European artists created an idyllic and even more romanticised vision of the island. Walter Spies, the Russian-born German polymath who visited Bali in 1927 and remained there until World War II, was part of a small yet influential expatriate community that shaped Bali’s image in the Western imagination.

Armed with an extensive knowledge of Balinese culture, Spies made his home in Ubud a mandatory stop for artists, writers, scholars and other visitors to Bali.17 He also encouraged Dutch artist Rudolf Bonnet, who arrived in 1929, to stay on in Bali. The two men, together with a member of the Ubud ruling family, Cokorda Gde Agung Sukawati, and several Balinese artists, including I Gusti Nyoman Lempad, became involved in the Pita Maha Guild, which sought to stimulate art and professionalise local artists.18 Bonnet also designed and planned the construction of Museum Puri Lukisan showcasing traditional Balinese art, whose main building was completed in 1956.19

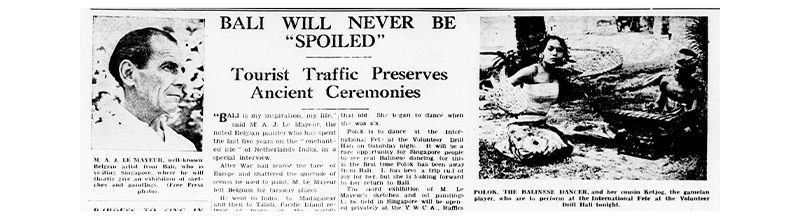

The Belgian artist Adrien-Jean Le Mayeur de Merprès, who settled in Bali in 1932 after extensive travels, created Impressionist paintings often featuring his Balinese wife and muse – the renowned legong dancer Ni Wayan Pollok Tjoeglik – in idyllic garden settings as well as Balinese women in sun-drenched scenes.20 His seaside home in Sanur was a popular spot for artists and tourists, offering dance performances and meals for a fee.21 Le Mayeur held four successful exhibitions in Singapore in 1933, 1935, 1937 and 1941.22 He said that Bali was his inspiration and his life. “I shall never leave Bali,” he once declared, “for I believe it will never be ‘spoiled’.”23

The four Singapore artists – Liu Kang, Chen Chong Swee, Chen Wen Hsi and Cheong Soo Pieng – visited Le Mayeur during their 1952 Bali trip. The artists also attended one of the couple’s popular tourist programmes consisting of “Balinese dance and gamelan performances together with a sumptuous meal served under the frangipani trees”.24

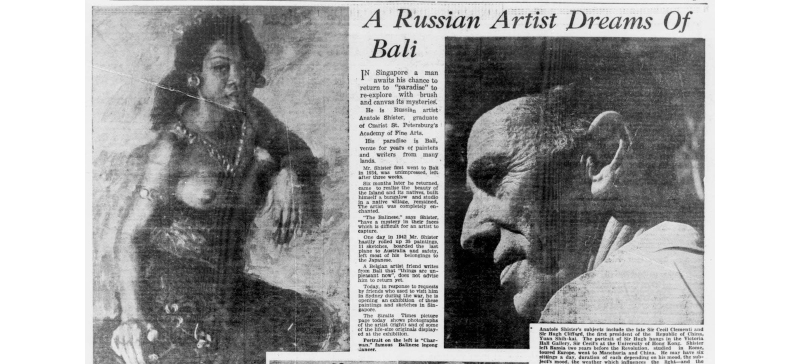

Other artists who captured Bali in their works and had exhibitions in Singapore include Julius and Tina Wentscher, the world-renowned painter and sculptor respectively, and the Russian artist Anatole Shister. The Wentschers held a joint exhibition at the YWCA in 1936. Their works, created in Java and Bali, included sculptures of a Balinese prince and a Balinese dancer, Sandri, and portrait paintings of Balinese girls.25

Shister showcased his Bali paintings and drawings at the Robinson’s department store in October 1947. The exhibition drew the colony’s elite, including Governor-General of Malaya Malcolm MacDonald, American Consul General Paul Josselyn and former Chinese Consul General Kao Ling Pai. Shister was “completely enchanted” by Bali. “The Balinese,” he said, “have a mystery in their faces which is difficult for an artist to capture.”26

Pages of Paradise

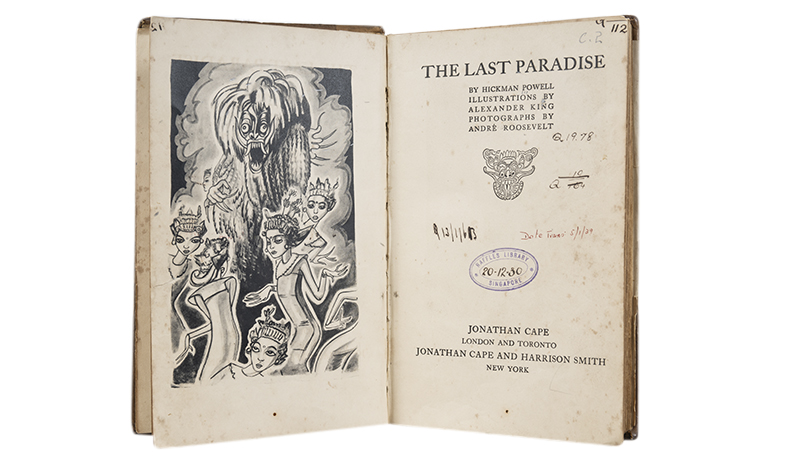

Written accounts by travellers also shaped public perception and understanding of Balinese culture, people and landscape. These narratives, which ranged from fiction to memoirs, served as tales for armchair tourists, offering them vicarious experiences and personal insights into the island.27 Some of these early authors include American journalist Hickman Powell, Austrian novelist Vicki Baum and Mexican artist Miguel Covarrubias.28

Ethnographic works by anthropologists Margaret Mead and Gregory Bateson portrayed Bali as a timeless paradise, unaltered by modernity. They documented Balinese culture extensively through thousands of photographs, film footage and detailed field notes, making a lasting impact in the field of visual anthropology.29

Amid the uncertainties immediately after World War II, there were fewer travellers to Bali as noted by Singapore’s Straits Times: “There are regular air services linking it with Batavia and a first-class hotel in the little capital, Denpasar, but the unsettled conditions in Asia have caused the tourist trade to dwindle almost to nothing. Only the most privileged or the most persistent are able to overcome the currency and visa difficulties which complicate travel in the East.”30

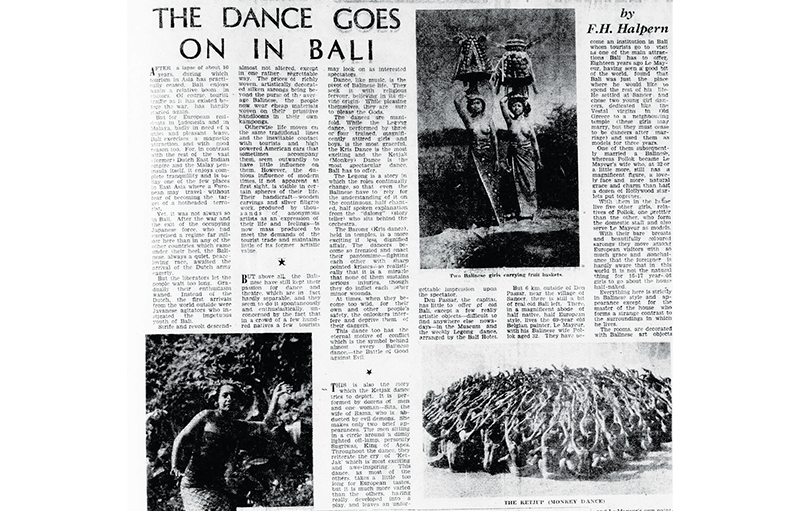

Tourism in Bali began to pick up in the late 1940s and early 1950s, and articles by Western travellers extolling the beauty of the island, as well as mentions of their visit to Le Mayeur’s home and meeting his wife Ni Pollok, were frequently published in Singapore’s newspapers. Writing for the Straits Times in 1949, F.H. Halpern was happy to find that after a lapse of about 10 years, Bali has “returned to complete tranquility” and the “inhabitants have changed so little in character customs and appearance”.31

Bali continued to enthrall travellers with its reputation as a paradise, and its charm was portrayed through images of bare-breasted women and descriptions of the arts, specifically the dances and music. Elizabeth E. Marcos, who visited Bali with two correspondents from the London Times, wrote in a 1950 Straits Times article: “This is the land of uncovered breasts; fabulous costumes; rich carvings and weird figures; lavish offerings to the gods; posturing men and women beating rhythm to the gamelan and perhaps where the transmigration of souls is a daily occurrence.” Marcos added: “As I sat under the arbor of J. Le Meyeur’s garden, pelted by frangipani and bougainvillea blossoms, watching Pollok in a difficult pose, straining to hold her arms in a dance movement, while her husband hurried to catch the last rays of the dying sun, I had the most unsophisticated feeling of having been transported into paradise.”32

Bali in Entertainment

The film industry further popularised the image of Bali not only in the West, but in Singapore too. André Roosevelt and Armand Denis’s “educational documentary” Goona Goona: An Authentic Melodrama of the Island of Bali (1932), shot entirely on location, was a huge success in America.33 “Goona goona” became a popular slang for sex appeal in the United States, and later a general term for native-exploitative films set in remote parts of the world.34 (Originally, “goona-goona”, or guna-guna, refers to an Indonesian term for love spells cast upon unwilling victims.)35

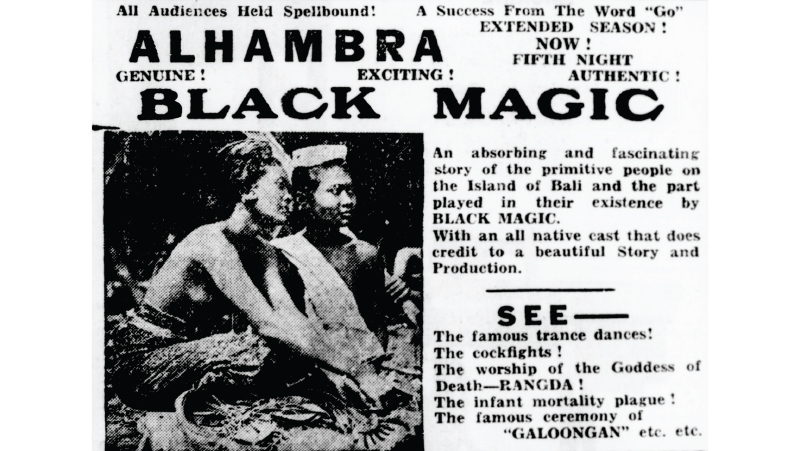

In Singapore, one of the earliest mentions of a screening of a Bali-based film was in 1934 titled Black Magic at the Alhambra theatre. This was likely Goona Goona but released under a different name.36 Another film shot on location in Bali was Legong: Dance of the (Temple) Virgins, which opened in Singapore in 1935 at the Alhambra, featuring an all-Balinese cast and filmed in technicolour. Centred on a legong dancer and a gamelan musician, the film was a box-office success in America and played for 10 weeks at the New York World Theatre in 1935.37

Balinese dance troupes first gained international exposure at the Colonial Exhibition in Paris before gradually touring the world, presumably as part of cultural missions.38 In 1935, a group known as the Royal Balinese Dancers performed at the Capitol in Singapore. Comprising 40 dancers and gamelan musicians, the troupe presented a programme of 11 items which included stories from the Hindu epic Mahabharata as well as Balinese, Javanese and Dayak dances. The following year, after a successful tour of India, Burma (Myanmar) and Ceylon (Sri Lanka), the same troupe returned to Singapore for another performance.39

In 1952, the Indonesian Fine Art Movement Troupe performed at the Victoria Theatre on their way back home from the Colombo Exhibition. The 50-member strong troupe included Sumatran and Balinese dancers.40

Bali in the Chinese Imagination

Bali attained some prominence in the Chinese-speaking world in 1935 when Legong: Dance of the Virgins (蓬岛春光) was screened in Shanghai. This was also the year that a touring Balinese dance troupe stopped by Shanghai and Hong Kong.41

The image of Bali as an island paradise, famous for its beautiful women, was further promoted through various publications.《良友画报》(Young Companion), a popular magazine launched in Shanghai in 1926 and widely circulated within China as well as Southeast Asia, published two features on Bali in May 1935 and December 1939. In the title of both features, Bali was referred to as “蓬岛” (Isle of Penglai), alluding to the mythical mountain island where immortals reside.42

Nearer home, this image of Bali as a divine realm was also evident in《荷属东印度概览》(Netherlands East Indian Sketch), a 1939 introductory book to the Netherland East Indies with a focus on the Chinese communities. Published in Singapore, the book described Bali as “仙天福地” – a paradise where immortals live.43

While Bali was typically touted as an exotic location with its beautiful and charming women, other aspects of the island such as Balinese dances, arts and crafts, temples, and religious and cultural practices, like cremation rituals and cock-fighting, were also showcased. As early as 1931, 《中华图画杂志》(The China Pictorial), another popular magazine founded in 1930 in Shanghai, described Bali as “mysterious” and introduced the history and culture of Bali accompanied by photographs in a feature story.44

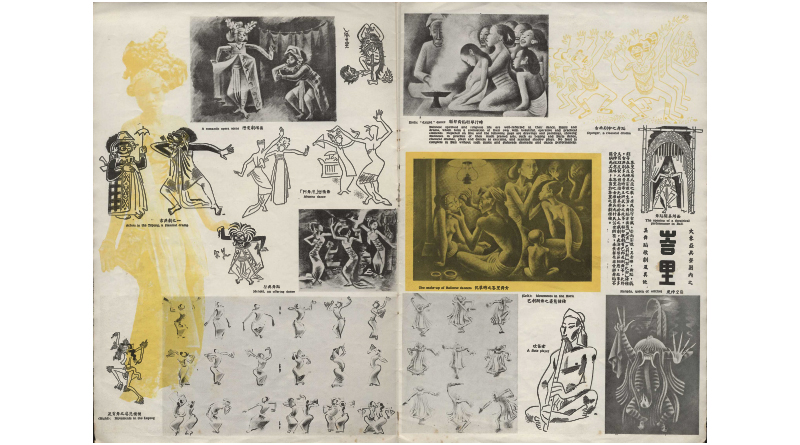

The July 1942 issue of《昭南画报》(Syonan Gaho) published in Singapore during the Japanese Occupation, featured images of Balinese dance and performances, which captured the spiritual and religious aspects of Bali. Among the images were illustrations by Covarrubias.45

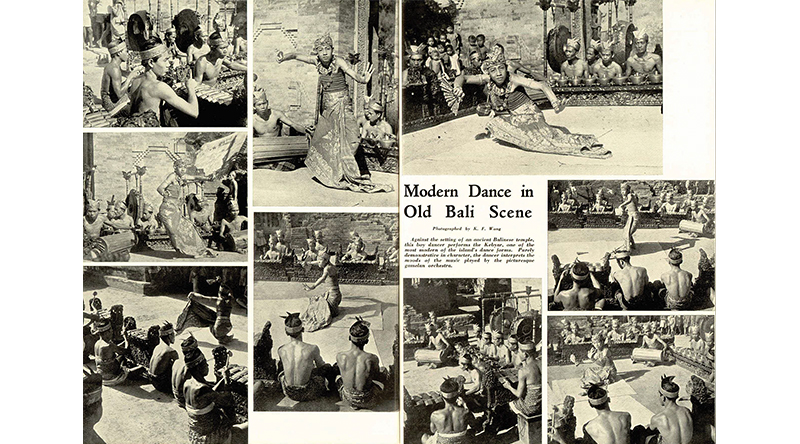

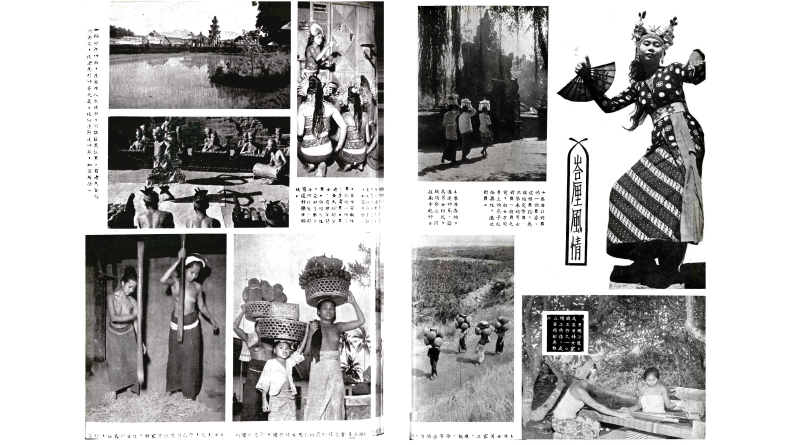

The inaugural issue of 《星洲周刊》(Sin Chew Weekly), published on 19 April 1951, included photographs by K.F. Wong featuring aspects of Balinese life, including different Balinese dances.46

The Enduring Image of Bali

The lasting image of Bali as an island paradise showcases the remarkable power of perception and representation. From the early Dutch encounters to the artistic endeavours of the 20th century – including the transformative 1952 trip by Singapore’s pioneering artists – Bali’s influence has extended far beyond its shores, enriching art, literature and popular culture across the seas. This romanticised portrayal of Bali, while captivating, exists alongside the complex realities of its people, culture and history.

Nadia Ramli is a Senior Librarian (Outreach) with the National Library Singapore. She writes about the visual and literary arts, and has conducted numerous outreach programmes advocating information literacy.

Nadia Ramli is a Senior Librarian (Outreach) with the National Library Singapore. She writes about the visual and literary arts, and has conducted numerous outreach programmes advocating information literacy. Goh Yu Mei is a Librarian at the National Library Singapore, working with the Chinese Arts and Literary Collection. Her research interests lie in the intersection between society, and Chinese literature and arts.

Goh Yu Mei is a Librarian at the National Library Singapore, working with the Chinese Arts and Literary Collection. Her research interests lie in the intersection between society, and Chinese literature and arts.NOTES

-

The movie is based on American author Elizabeth Gilbert’s bestselling memoir, Eat, Pray, Love: One Woman’s Search for Everything Across Italy, India and Indonesia, published in 2006. The memoir chronicles Gilbert’s travels around the world after her divorce and what she discovered. The eBook is available on NLB OverDrive. ↩

-

Jeffrey Say and Yu Jin Seng, “The Modern and Its Histories in Singapore Art,” in Intersections, Innovations, Institutions: A Reader in Singapore Modern Art (Singapore: World Scientific Publishing Co. Pte. Ltd., 2023), 26. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 709.595709034 INT) ↩

-

Liu Kang, oral history interview by Tan Beng Luan, 13 January 1983, transcript and MP3 Audio, Reel/Disc 39 of 74, National Archives of Singapore (accession no. 000171), 364. [English version translated and annotated by Tay Jun Hao and Alina Soh.] ↩

-

Michel Picard, Bali: Cultural Tourism and Touristic Culture (Singapore: Archipelago Press, 1996), 18–19. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 959.86 PIC) ↩

-

Picard, Bali, 19; David Shavit, Bali and the Tourist Industry: A History, 1906–1942 (Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland & Co., 2003), 7. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSEA 338.47915986 SHA) ↩

-

Shavit, Bali and the Tourist Industry, 7; Willard A. Hanna, Bali Chronicles: A Lively Account of the Island’s History from Early Times to the 1970s (Singapore: Periplus, 2004), 170. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSEA 959.86 HAN) ↩

-

Adrian Vickers, Bali: A Paradise Created (Tokyo: Tuttle Publishing 2012), 113, 130–32. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSEA 959.862 VIC); Shavit, Bali and the Tourist Industry, 10–11. ↩

-

Shavit, Bali and the Tourist Industry, 9. ↩

-

Picard, Bali, 22; Shavit, Bali and the Tourist Industry, 24. ↩

-

Orient Touring Company, Travel Through the Mystic Isles of Java, Sumatra and Bali (n.p.: n.p., 1926). (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 915.980422 ORI-[SEA); “The Romance of the East, the Comfort of the West in Java, Sumatra, Bali,” in Indonesia Travel Ephemera (Java: Travellers Official Information Bureau of Netherland India, c. 1920s –1930s). (From John Koh Collection, National Library Singapore, call no. RCLOS 915.9804 JOH-[JK]). Donated by Cynthia and John Koh. ↩

-

Picard, Bali, 24; Shavit, Bali and the Tourist Industry, 50. ↩

-

Jojor Ria Sitompul, “Visual and Textual Images of Women: 1930s Representation of Colonial Bali as Produced by Men and Women Travellers” (PhD diss., University of Warwick, 2008), 116, http://go.warwick.ac.uk/wrap/4107. ↩

-

Sitompul, “Visual and Textual Images of Women,” 144. ↩

-

Shavit, Bali and the Tourist Industry, 18. ↩

-

Shavit, Bali and the Tourist Industry, 73–75; John Seed, “The Last Orientalists: European Artists in Colonial Bali,” Sotheby’s, 26 February 2020, https://www.sothebys.com/en/articles/the-last-orientalists-european-artists-in-colonial-bali. ↩

-

Anak Agung Ayu Wulandari, “The Role of Pitamaha in Balinese Artistic Transformation: A Comparison Between Kamasan and Gusti Nyoman Lempad Artistic Style,” Humaniora 7, no. 4 (October 2016): 463–72, https://journal.binus.ac.id/index.php/Humaniora/article/download/3599/2979/0; Shavit, Bali and the Tourist Industry, 81. ↩

-

Seed, “The Last Orientalists.” ↩

-

Seed, “The Last Orientalists.” ↩

-

Shavit, Bali and the Tourist Industry; Seed, “The Last Orientalists.” ↩

-

“Y.W.C.A. “Drenched in Sunlight,” Straits Times, 28 February 1933, 12; “Bali Through Eyes of a Painter: Exotic Colours of the South Seas,” Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, 13 March 1935, 9; “Untitled,” Straits Times, 27 February 1937, 1; “Balinese Dances at Art Exhibition Today,” Straits Times, 8 March 1937, 13; Mary Heathcott, “Le Mayeur’s Exhibition: Polok Amid Paintings of Her Native Bali,” Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, 21 May 1941, 5. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Bali Will Never Be ‘Spoiled’,” Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, 26 February 1937, 6. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Gretchen Liu, Bali 1952: Through the Lens of Liu Kang: The Trip to Java and Bali by Four Singapore Pioneering Artists (Singapore: National Library Board, 2025), 92, 95. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 779.995986 LIU) ↩

-

“On Show at Y.W.C.A.: Art of Julius Wentscher,” Morning Tribune, 27 March 1936, 3; “Art Show at Y.W.C.A.: Painting and Sculpture,” Malaya Tribune, 27 March 1936, 15. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“A Russian Artist Dreams of Bali,” Straits Times, 18 October 1947, 9; “‘Singapore Needs an Art Gallery’,” Straits Times, 19 October 1947, 7. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Adrian Vickers, comp. and introduction, Travelling to Bali: Four Hundred Years of Journeys (Kuala Lumpur: Oxford University Press, 1994), xiii–xvi. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSEA 959.86 TRA) ↩

-

“A Timeless Existence in New Bali,” Straits Times, 24 February 1949, 8. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

F.H. Halpern, “The Dance Goes on in Bali,” Malaya Tribune, 18 November 1949, 5. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Elizabeth E. Marcos, “This Is Bali,” Straits Times, 23 February 1950, 11. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Michael Atkinson, “Goona Goona: An Authentic Melodrama of the Isle of Bali,” San Francisco Silent Film Festival, accessed 8 January 2025; https://silentfilm.org/goona-goona-an-authentic-melodrama-of-the-isle-of-bali/; Sitompul, “Visual and Textual Images of Women”; Shavit, Bali and the Tourist Industry, 104. ↩

-

Shavit, Bali and the Tourist Industry, 101. ↩

-

Sitompul, “Visual and Textual Images of Women.” ↩

-

“‘Black Magic’ at the Alhambra,” Malaya Tribune, 24 August 1934, 14. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“‘Legong’ (‘Dance of the Temple Virgins’),” Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, 23 May 1935, 7. (From NewspaperSG); Peter J. Bloom and Katherine J. Hagedorn, “Legong: Dance of the Virgins,” San Francisco Silent Film Festival, accessed 25 January 2025; https://silentfilm.org/legong-dance-of-the-virgins/. ↩

-

“Balinese Dancers in Singapore,” Straits Times, 22 January 1935, 13; “Royal Balinese Dancers,” Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, 30 January 1935, 9; “Royal Balinese Dancers,” Morning Tribune, 7 December 1936, 7; “Royal Balinese Dancers,” Pinang Gazette and Straits Chronicle, 13 August 1936, 8. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Bali – In Song and Dance,” Singapore Standard, 27 March 1952, 10; “To-night the Indonesia Clubs Brings Bali to You,” Singapore Standard, 24 March 1952, 5. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Hua Xing 华兴 [photographer], “Pengdao Zhenmianmu” 蓬岛真面目 [The Island Bali and Balinese], Liangyou Huabao 良友画报 [Young Companion] 14, no. 105 (May 1935): 34. (From National Library Singapore, call no. Chinese R 059.951 YC). Donated by the Singapore Federation of Chinese Clan Associations. ↩

-

Liangyou Huabao 良友画报 [Young Companion] 14, no. 105 (May 1935) and 22, no. 149 (December 1939). (From National Library Singapore, call no. Chinese R 059.951 YC). Donated by the Singapore Federation of Chinese Clan Associations. ↩

-

Liu Huan Ran刘焕然, ed., Heshu Dongyindu Gailan 荷属东印度概览 [Netherlands East Indian Sketch] (新加坡: 南洋报社, 1939), chapters 4, 16. (From Ya Yin Kwan Collection, National Library Singapore, call no. Chinese RDTYS 959.8 LHJ) ↩

-

“Shenmi zhi Balidao” 神秘之峇厘島 [The mysterious Bali island in the Dutch East Indies], Zhonghua Tuhua zazhi_中华图画杂志 [_The China Pictorial] no. 7 (November 1931): 19–20. (From 中文期刊全文数据库 (1911–1949) [Chinese Periodical Full-text Database (1911–1949], via NLB eResources website) ↩

-

Zhaonan Huabao 昭南画报[Syonan Gaho] 1, no. 2 (July 1942), n.p. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RRARE 940.54259 SG) ↩

-

Xingzhou Zhoukan 星洲周刊 [Sin Chew Weekly], 19 April 1951, n.p. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RCLOS 059.951 SCW) ↩