Writing the NLB Story

Established in 1995, the National Library Board was conceived as one of many levers to transform Singapore’s economy and culture.

By Hong Xinyi

While the National Library Board was established in 1995, the motivation behind its launch goes back at least to the early 1990s and perhaps even earlier.

In the early 1990s, the faint contours of the present technology-saturated, hyperconnected world came into focus as rudimentary versions of the web browser and website debuted, and the term “information superhighway” started to become popular.

Speaking at a gala dinner for the National Computer Board (NCB) in 1991, Prime Minister Goh Chok Tong noted that with the information superhighway emerging, the future was “rushing at us” once more. “Singaporeans have the opportunity to be part of the challenges and rewards of an exciting future,” Goh said. “But the cost of the entrance ticket is having to accept constant learning and relearning of new things and constant adapting to new living and working environments.”1

In Singapore, this work of constant adaptation had in fact started in the 1980s, when the NCB was formed to implement the computerisation of the civil service, and a national IT plan was formulated. Embracing digitalisation was a means to a larger end – engineering a shift towards a more diversified knowledge-based economy. Over the next two decades or so, a concerted array of public policies would seek to position Singapore as a global hub, orientate manpower training and the education system for a globalised technology-driven world, and unlock the potential of new sectors ranging from research and development (R&D) to the creative industries.

“Why were we doing all this? It was all about reinvention, about making Singapore competitive,” said Dr Tan Chin Nam, the first chairman of the National Library Board (1995–2002). “We had to find new ways of making a living, of staying relevant,” he told BiblioAsia in an interview in February 2025.2 During those years, he was on the frontlines of this transformation through his leadership roles at not just the NLB, but also the NCB, Economic Development Board (EDB), Ministry of Manpower, Ministry of Information, Communications and the Arts (MITA), and several other agencies and statutory boards. It was a time when many levers in the public sector were created and refined to help engender Singapore’s reinvention.

The national library system was one of these levers. After all, the jobs in a knowledge-based economy could only be filled by people who were up to speed with the world’s innovations and ready to adapt to and lead change. And the library was all about helping people learn. There was just one problem: this system was not in very good shape.

Sparks of Inspiration

With roots dating back to 1837, the National Library Singapore had made tremendous strides since its beginnings as a school library within the Singapore Institution (later renamed Raffles Institution).3 Under the dynamic leadership of Hedwig Anuar, its much-beloved director from 1965 to 1988, the network of libraries and membership grew, and the process of computerisation had begun.4

But the system was poorly funded. Librarians with a basic bachelor’s degree were among the lowest paid in the public service, with small annual salary increments and poor promotion prospects.5 Facilities and collections were not in great shape: libraries were often cramped, and the average shelf-life of a book was about 11 years, which meant it was not uncommon for books in circulation to show signs of wear and tear.6

A 1992 survey found that the public felt the library system was “generally inadequate” in the range and accessibility of its collection, services and facilities. Respondents wanted better classification, more study facilities, and better and more user-friendly computer systems.7

By then, change was on the way. In 1990, some divisions within the Ministry of Community Development and the Ministry of Communications and Information were placed within the newly formed MITA, which became the library’s parent ministry. A year later, George Yeo, then 37, became the first minister of MITA.

As Yeo pondered the national library system in Singapore against the backdrop of the country’s percolating transformation in the 1990s, he felt that it was time to do things differently. At the time, there was a formula, one that was simply repeated – when the population of a part of Singapore reached a certain level, budget would be allocated for a standalone library. Each library would always have a wall dedicated to the photographs of the President and First Lady. Libraries also kept office hours – meaning they were closed when people got off work, and during the weekends.

“It seemed so antiquated and unsuited to our way of life,” he recalled in an interview with BiblioAsia in January 2025.8 “People should be able to go to library when they are free. And did we need a shrine to the President and First Lady when space was so precious? I was a young man then, and maybe I was a bit insensitive, but to me, it was ridiculous. And I thought: we had to break the mould.”

In 1992, Yeo decided to ask Tan, then the chairman of NCB and managing director of EDB, to head a committee that would examine how to reinvent the library.9 Tan’s familiarity with technology was an obvious strength for reshaping a library system for the internet era. Equally important was the fact that “Chin Nam is good with people”, Yeo explained. Changing the library would mean changing its culture, and that would require strong people skills.

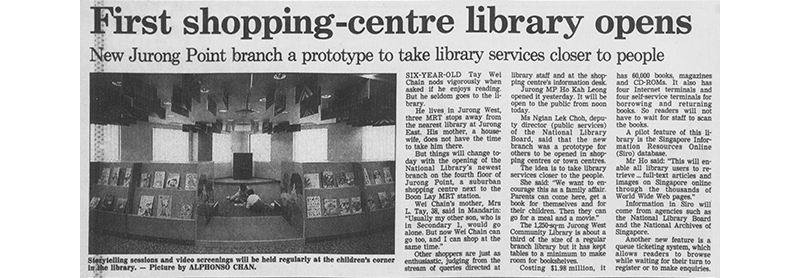

Of that first conversation about the library, Tan said of Yeo: “He wanted to challenge conventional wisdom. For instance, he asked: ‘Why shouldn’t a library be located in a shopping mall?’ That question gave me a sense of the mandate – for this reinvention, we could dream of anything, in order to make sure that the library would be able to service its users.”

So Tan got to work. Twenty representatives from the public, academic and private sectors were appointed to the Library 2000 Review Committee. Visits to libraries in San Francisco, New York, London, Paris and Shanghai were organised to gather ideas. “Because you must be humble, you have to learn from others,” Yeo explained.

The San Francisco Public Library, for instance, was designed for the digital age – users were always no more than a metre away from a plug-in point. That made an impression. Yeo also recalled observing how certain libraries were vibrant event spaces, and how their collections mirrored their communities’ and countries’ cultural histories.

His longstanding interest in global knowledge arbitrage also influenced the library’s eventual transformation. “Singapore is where domains intersect and overlap,” Yeo said. Mediating and translating between these different domains – for instance, as an entrepot servicing traders from the East and West – had been the country’s main way of making a living for a long time, and he believed it to be Singapore’s most enduring advantage.

The diversity within Singapore had made Singaporeans instinctively skilled at adapting to people from different cultures, he thought. But instinct was not enough. “Arbitrage should be based upon knowledge about these cultures.” The library, he felt, could provide this knowledge.

A Revolutionary Report

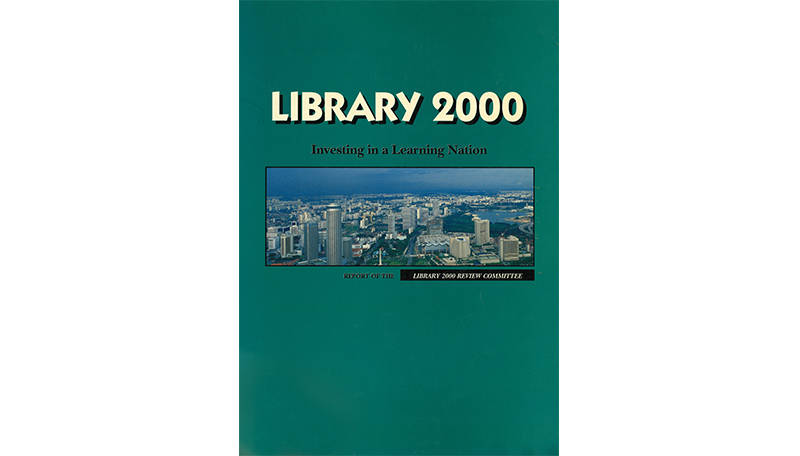

The Library 2000 report was released in March 1994. In his memoirs, published in 2024, Yeo described its proposals as “revolutionary”.10

For a start, there was the report’s subtitle – Investing in a Learning Nation. “That was the first time the notion of a learning nation, and investing in the learning capacity of the nation, was conceived and presented, which I think is very, very important,” said Tan.

The library, he wrote in the report, should be positioned as “an integral part of our national system actively supporting Singapore as a learning nation”, helping Singaporeans to learn faster and apply knowledge better than others. “This differential lead in our learning capacity will be crucial to our long-term national competitiveness in the global economy where both nations and firms compete with each other on the basis of information and knowledge,” he wrote.

Recommendations from the Library 2000 Report

The Library 2000 report drew up the roadmap for the Singapore’s library system today. Among other things, it proposed that a National Reference Library and Specialised Reference Libraries should be complemented by regional, community and neighbourhood public libraries of varying sizes and differentiated collections and services.

It noted that Singapore’s libraries should be linked by computer networks to overseas libraries and databases, and that there should be more emphasis on developing multilingual and regional collections “to serve the needs of the various segments of users in Singapore and to support our regionalisation efforts”.

To compete with all the other leisure options out there, libraries should innovate, and learn from other sectors such as retail to create a lively and enjoyable environment. This would help debunk the stereotype that libraries were “old, unfriendly and uninteresting”.

Libraries should also build stronger links with businesses and communities. For instance, they could be integrated into cultural, educational and commercial complexes, instead of being housed in standalone buildings.

To accomplish these goals, the report proposed better training, remuneration and career pathways for librarians; adopting new technologies to help users learn, and to expedite the automation of library operations to improve services; and setting up a statutory board to spearhead the implementation of the report’s recommendations and to realise its vision of transformation for the library.

In March 1995, Yeo elaborated on this transformation in a speech at the Digital Libraries Conference. The library would develop along the twin tracks of technology and culture, he said.11

The importance of technology was perhaps more self-evident – by then, internet terminals were starting to appear in libraries here. But culture was no less essential. It was culture that “regulates the way human beings cooperate and compete”, he said. “Throughout history, public libraries have not only been repositories of information, they have also been temples of culture… We need access to all sources of knowledge. What we want is to make Singapore a hub for knowledge arbitrage. But we also want to preserve our sense of self and family which is why there must always be a cultural emphasis to all that we do.”

Translating Theory into Practice

About six months after Yeo’s speech, the National Library Board (NLB) was formed as a statutory board on 1 September 1995. This structure meant that it had more discretion in financial and human resource matters, such as market-based salaries.12

Tan was appointed its chairman, and he recruited Dr Christopher Chia, a colleague from his NCB days, as its chief executive. Chia used to head the NCB’s R&D arm. “So I got him involved with the expectation that we would be able to inject a lot of IT expertise into the transformation of the library,” said Tan.

At that point, Chia was in the private sector and had spent just 10 months in his new job.13 He decided to return to the public sector for two reasons. First, he was very fond of the library. “I must have gone through the entire collection of the national library’s fairy tales, mysteries and fantasies when I was a child,” he told BiblioAsia in January 2025.14 It also felt like an opportunity to continue his previous work in promoting the wider adoption of technology, now in another way through the library.

Chia’s first order of business was to secure a budget for Library 2000’s ambitious proposals. “A plan is only as good as its implementation, right? So we spent up to a year translating the Library 2000 plan into a set of tangible outcomes, in order to get funding support.”

He set ambitious targets as well, aiming for three times the number of loans, visitorship and membership within the next five years. “If you want an increase by 5 percent, you don’t need me. That will happen anyway,” he explained. “But we wanted to do something significant, so we offered those numbers. Because when you go to the Finance Ministry, if you just say, I want to grow something, but you don’t offer a significant outcome, you’re not going to get anywhere.”

It worked and the purse-strings loosened. In 1996, it was announced that NLB would spend over S$1 billion over the next eight years on its facilities, collections and staff training.15 It was not a huge sum in the larger scheme of things, but it was a notable move at a time when many countries were cutting their investments in libraries.16

With funding secured, actual change got underway, and rapid prototyping became a key strategy for introducing innovations.

Although at the time it had already been decided that the National Library building on Stamford Road would be demolished, it had a lively last chapter. Between 1998 and its eventual demolition in 2005, it was used as a testbed for new ideas, many of which were later replicated in new libraries. These included a café, live music performances and talks on topics ranging from health to life sciences.

Planning for new libraries was professionalised with the setting up of a properties team, whose members developed expertise in working with architects and interior designers, and optimising the placement of new features such as checkout machines. New standards for operations and frontline customer service were established, and customer service training and more objective staff evaluation criteria were introduced.17

Getting the librarians to accept change, however, was not easy. Few people like change, especially radical change. Fortunately, the responsibility of bridging the old ways with the new landed on the shoulders of R. Ramachandran. Known as Rama to the staff, he was the first director of the National Library after NLB was formed. In many ways, he was the ideal person to be the bridge because he was a dyed-in-the-wool librarian himself. He had joined the National Library back in 1969 as a library officer, and had risen to be the deputy director of its reference and support services when he was appointed to the Library 2000 committee in 1992. (He eventually retired as NLB’s deputy chief executive in 2004.)18

“Many new hires from the technology sector joined NLB in the 1990s,” Rama told BiblioAsia in February 2025.19 Newbies and the long-serving librarians had to get used to one another, and they did, eventually. He took on the role of interfacing – arbitraging, you might say – between the librarians and the senior management.

“I learned a lot of things from the new people too, like public relations, and how to bring in new ideas,” he said. The new services and events he helped to introduce included an electronic reference service for remote library users, and the Asian Children’s Festival.

To reassure staff during this time of change, the management said there would be no retrenchments. Job scopes were redefined and enlarged, and staff also got new uniforms, salary raises, business cards, improved workspaces as well as emails and computer access. “These enhancements went down well with librarians,” said Rama.

He added that Chia was able to strike a balance between “not rocking the boat” and being honest with librarians about the need for change. There were many communication sessions and opportunities for staff to have their voices heard. For instance, during the first year of NLB’s existence, 65 percent of the 3,337 suggestions from the staff suggestion scheme were implemented. Chia visited one to two branches every week to get a better sense of how things were on the ground. By 1998, the attrition rate was close to zero.20

“I have discovered when you have a vision, you have to also make sure that there’ll be buy-in of that vision,” said Tan of his approach to change management. “So I think is a very important to have stakeholder engagement. You have to respect the incumbents. You have to provide capacity development, new training, so that everybody can work together and be part of the journey of co-creating new value.”

Resistance to change also ebbed when staff started seeing the tangible results of new ideas. The switch away from the tedious and time-consuming manual processing of library books was one example. Chia and his team collaborated with a local company to come up with a system where radio frequency identification was used to automate the check-out and returning of books. The first prototype was rolled out at the Bukit Batok Community Library, which opened in November 1998. “It worked beautifully,” said Chia. “When staff from other branches started asking ‘when is our turn?’, I knew that we had turned a corner.”

A Lasting Impact

By 2001, visitorship had quadrupled, the collection had tripled in size, and membership and the library physical space had doubled. The loan rate also increased from 10 to 25 million books, and time spent in queues was reduced from an hour to 15 mins.21 That year, the NLB was featured in a case study by the Harvard Business School. Case studies of real-world organisations that illustrate business concepts in action form the backbone of the curriculum at this institution.22

Today, the effects of the Library 2000 recommendations can clearly be seen as many of the proposals were implemented – from a network of libraries of different sizes, to libraries with vibrant designs and tech-aided services that are embedded within shopping malls.

The NLB has constantly sought to reinvent itself with more strategic plans. In 2005, there was the Library 2010: Libraries for Life, Knowledge for Success report. This was followed by “Libraries for Life” in 2011 and the latest, LAB25 (“Libraries and Archives Blueprint 2025”), in 2021.

And that journey of change and transformation, for both the library and Singapore, is far from over. Singaporeans are still buffeted by great changes – new technologies such as artificial intelligence are reshaping the world, and information has long been at everyone’s fingertips, thanks to ubiquitous digital devices. How should the library approach its mission of helping people learn today?

“I was in Huawei’s Dongguan campus recently, where they have a magnificent European-style library,” Yeo replied when asked this question. “The idea behind it is to inspire Huawei’s staff. Bookshops are governed by the bottom line. But a public library can go beyond that.” A technology-saturated, hyperconnected world is frenetic; the library can be a space for calm and reflection, he believed. “It can be a place where people can take a step back and see things against the sweep of history and geography. And once you realise how little you know, you become more humble, and less quick to judge and criticise.”

For Tan, leaning into the function of the library as a social space may be a good path forward. “Human beings are social animals, right? We are very fortunate because the library is very much part of our social fabric, and I think as NLB continues to innovate, it will continue to perform a very important role in continuous learning.”

When the National Archives of Singapore became part of the National Library Board in 2012, it was, in many ways, a homecoming. The archives had begun life in the late 1930s as part of the old Raffles Library and Museum, the predecessor institution of the National Library.

The history of the archives in Singapore dates back to 1938 with the appointment of Tan Soo Chye as the first Archivist to manage the historical records of the archives unit at the Raffles Library and Museum.

In January 1955, the administration of the Raffles Library was separated from that of the Raffles Museum and the archives unit came under the Raffles Library. (The Raffles Library was renamed Raffles National Library in 1958 and then the National Library in 1960).

The archives unit became a separate unit – the National Archives and Records Centre (NARC) – in August 1968. The newly established unit took over the management, custody and preservation of public archives and government records from the National Library. Hedwig Anuar, the director of the National Library, was concurrently appointed the first director of the NARC.

Two years later, in January 1970, the NARC moved into its own premises at 17–18 Lewin Terrace on Fort Canning Hill.

The NARC was expanded in 1979 when the Oral History Unit was set up as a department under the NARC. The mission of the Oral History Unit was to collect and document the memories of people through oral history recordings. In 1981, the NARC was renamed the Archives and Oral History Department following the merger of the Oral History Unit with the NARC.

In May 1984, the Archives and Oral History Department relocated to the Old Hill Street Police Station, sharing the space with several government agencies. The new premises had better facilities such as a bigger climate-controlled archival repository. Just a year later, the Archives and Oral History Department was split into the National Archives and the Oral History Department.

In August 1993, the National Archives, the Oral History Department and the National Museum became part of the National Heritage Board. The National Archives and the Oral History Department became a single entity known as the National Archives of Singapore, and the Oral History Department was renamed the Oral History Centre.

In 1997, the National Archives of Singapore moved into the former Anglo-Chinese Primary School building at 1 Canning Rise, where it remains to this day. Finally, in November 2012, the National Archives of Singapore became an institution of the National Library Board.

The National Archives of Singapore building at Canning Rise. Collection of the National Library Board.

Hong Xinyi is a writer, editor, translator and producer. She is the author of The Remaking of Singapore’s Public Libraries (2019). She also runs dear humans, a newsletter, which features occasional dispatches on gender, technology and culture.

Hong Xinyi is a writer, editor, translator and producer. She is the author of The Remaking of Singapore’s Public Libraries (2019). She also runs dear humans, a newsletter, which features occasional dispatches on gender, technology and culture.Notes

-

Goh Chok Tong, “Speech by the Prime Minister, Mr Goh Chok Tong, at the National Computer Board 10th Anniversary Gala Dinner on Thursday, 26 September 1991, at the Raffles Hotel Ballroom, Westin Plaza Hotel at 7.40 PM,” transcript, Ministry of Information and the Arts. (From National Archives of Singapore, document no. gct19910926) ↩

-

Tan Chin Nam, interview, 21 February 2025. ↩

-

Singapore Institution Free School, Fourth Annual Report 1837–38 (Singapore: Singapore Free Press Office, 1838), 5. (From National Library Online) ↩

-

Zaubidah Mohamed and Gladys Low, “Hedwig Anuar,” in Singapore Infopedia, National Library Board Singapore. Article published August 2016. ↩

-

Library 2000 Review Committee, Library 2000: Investing in a Learning Nation: Report of the Library 2000 Review Committee (Singapore: SNP Publishers and Ministry of Information and the Arts, 1994), 12. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 027.05957 SIN-LIB]) ↩

-

Roger H. Hallowell, Neo Boon Siong and Carin-Isabel Knoop, Transforming Singapore’s Public Libraries (Boston: Mass, Harvard Business School Publishing, 2001), 2. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RCLOS 027.45957 HAL-[LIB]) ↩

-

Library 2000 Review Committee, Library 2000, 4. ↩

-

George Yeo, interview, 31 January 2025. ↩

-

“Permanent Secretary (Information, Communications and the Arts),” Public Service Division, Prime Minister’s Office, 12 November 2007, https://isomer-user-content.by.gov.sg/147/19d2ea69-f9c3-44fd-a44e-0b097c6dbc6c/press-release—12-nov-2007-permanent-secretary-of-mica-retires.pdf. ↩

-

George Yeo Yong-Boon, George Yeo: Musings Series 3 (Singapore; Hackensack, NJ: World Scientific Publishing Co. Pte. Ltd., 2024), 154. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 959.57052092 YEO) ↩

-

George Yeo, “Libraries of the Future to Develop Along Twin Tracks,” Straits Times, 30 March 1995, 28. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Hallowell, Neo and Knoop, Transforming Singapore’s Public Libraries, 4. ↩

-

“Aztech’s Head of Research Resigns,” Business Times, 19 August 1995, 6. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Christopher Chia, interview, 13 January 2025. ↩

-

Koh Buck Song, “National Library to Spend $1b over 8 Years,” Straits Times Weekly Overseas Edition, 6 July 1996, 3. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Hallowell, Neo and Knoop, Transforming Singapore’s Public Libraries, 4. ↩

-

Hallowell, Neo and Knoop, Transforming Singapore’s Public Libraries, 6. ↩

-

Sitragandi Arunasalam, “R. Ramachandran,” in Singapore Infopedia, National Library Board Singapore. Article published 2016. ↩

-

R. Ramachandran, interview, 13 February 2025. ↩

-

Hallowell, Neo and Knoop, Transforming Singapore’s Public Libraries, 6. ↩

-

Hallowell, Neo and Knoop, Transforming Singapore’s Public Libraries, 1. ↩

-

Yannis Normand, “The History of the Case Study at Harvard Business School,” Harvard Business School Online, 28 February 2017, https://online.hbs.edu/blog/post/the-history-of-the-case-study-at-harvard-business-school. ↩