Books on Wheels: Singapore's Mobile Libraries

Between the 1960s and 1980s, libraries-on-wheels were a familiar sight as they travelled around Singapore bringing books to residents in rural and suburban areas.

By Gracie Lee

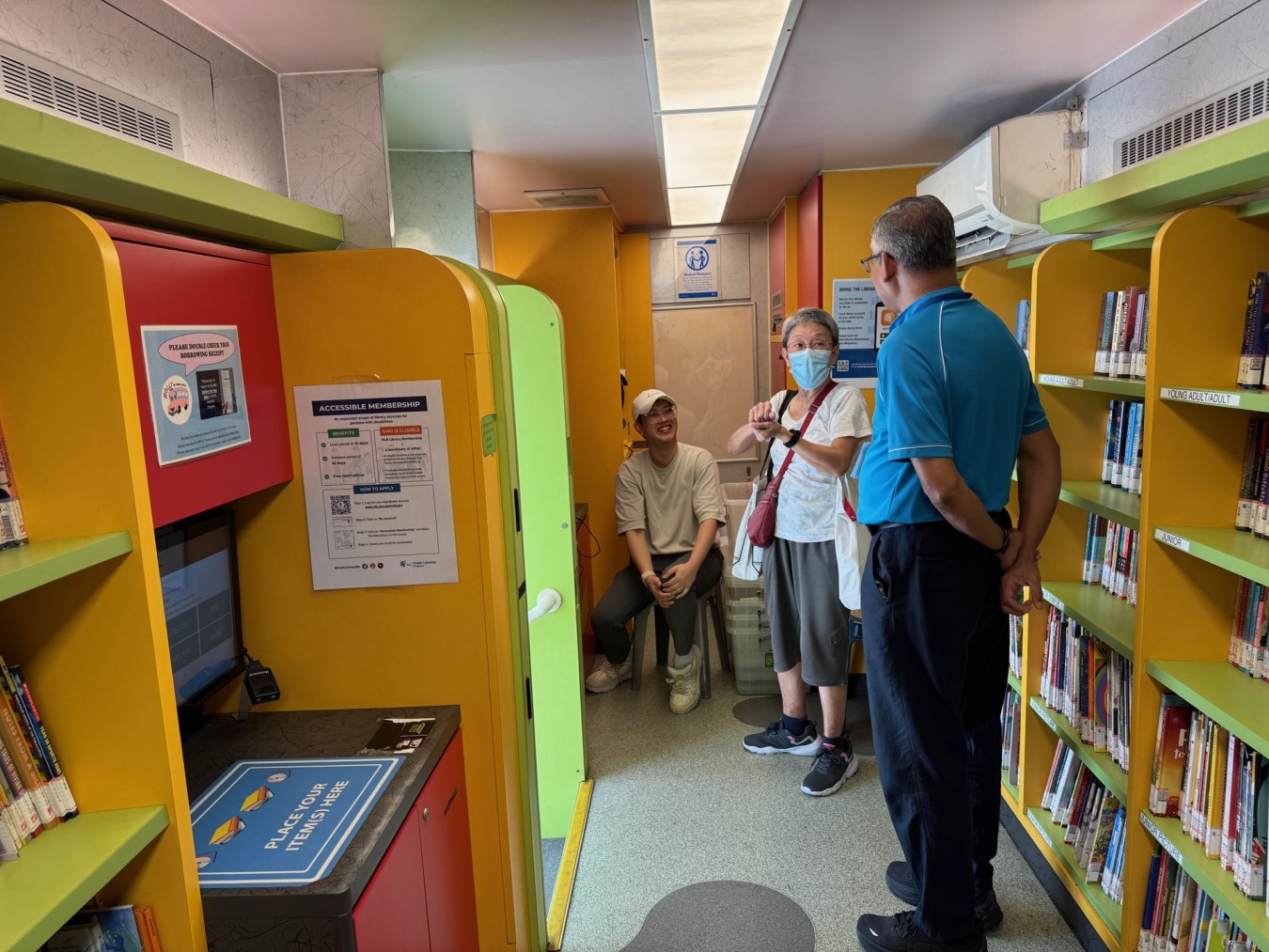

Library Officer Wesley Agustian (seated) and Assistant Library Officer Mohan M. chatting with a regular library user who travelled from Chinatown to Marine Terrace, where she borrowed 15 romance novels from Big Molly, 29 March 2025. The self-service borrowing station is seen on the left. Photo by Jimmy Yap.

Library Officer Wesley Agustian (seated) and Assistant Library Officer Mohan M. chatting with a regular library user who travelled from Chinatown to Marine Terrace, where she borrowed 15 romance novels from Big Molly, 29 March 2025. The self-service borrowing station is seen on the left. Photo by Jimmy Yap.On 31 January 1959, the Singapore Constitution Exposition opened at the former Kallang Airport to much fanfare. The two-month-long event was organised to celebrate the establishment of the State of Singapore and the new Constitution, a major milestone in Singapore’s transition to full internal self-government.1

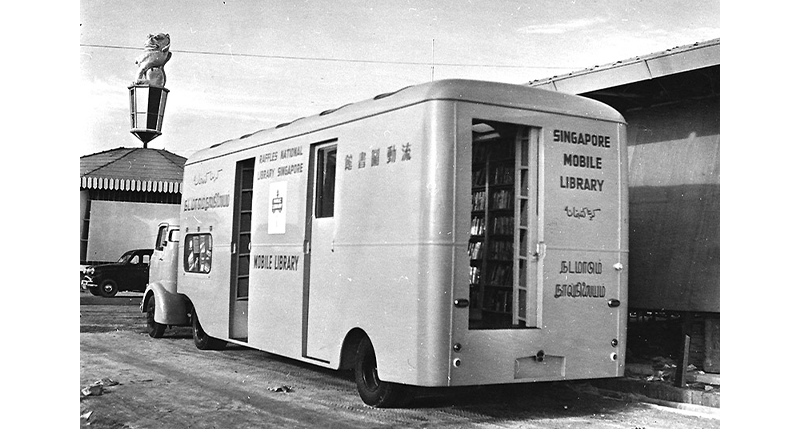

Among the 600 exhibitors from commercial and government sectors, an unexpected attraction made its public debut: the Raffles National Library’s mobile library van, which had been converted from a decommissioned army bus.2 Together with part-time branch libraries, the mobile library service was part of the library’s efforts to reach residents in outlying areas.

Plans for a Mobile Library Service

Efforts to modernise the Raffles Library (renamed Raffles National Library in 1958 and National Library in 1960) began in the mid-1950s ahead of its redesignation as a national library. These included a new National Library building on Stamford Road slated for completion in 1960, and the formation of the Library Extension Services comprising a mobile library service and part-time branch libraries.3 (In 1956, the government had approved a mobile library service to “determine the needs of branch libraries”.4)

The mobile van showcased at the exposition was procured through a United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) grant of US$2,000 in 1957 that was specifically designated for establishing mobile libraries for children. In addition to the van, the fleet also included two trailers that the library bought in 1959.5

The plan then was to dispatch these roving libraries to densely populated urban districts such as Tiong Bahru and Queenstown as well as to rural areas like Changi. “[The mobile libraries] will cater more for the non-English speaking people, for whom there were no adequate public library services at present,” Minister for Culture S. Rajaratnam told the Straits Times.6

Although the mobile library made its first public appearance in 1959, it was not immediately put to use due to the lack of qualified staff to drive and operate it. By then, it had become evident that the facilities at the Junior Library of the Raffles National Library were woefully inadequate to cope with the surge in borrowers after membership fees were abolished.7 In the first two months of 1958 alone, new children’s memberships tripled compared to the same period the previous year. The initial four months of 1959 saw a 69 percent increase in books borrowed by youths compared to the same period the year before. The demand was great as more than half of the population were under the age of 20 in 1957.8

The Mobile Library Service Begins

In April 1960, Hedwig Anuar from the University of Malaya Library in Kuala Lumpur was seconded to the Raffles National Library in Singapore to oversee the opening of the new National Library building. Under her watch as director, the mobile library van finally took to the roads on 6 September 1960.9

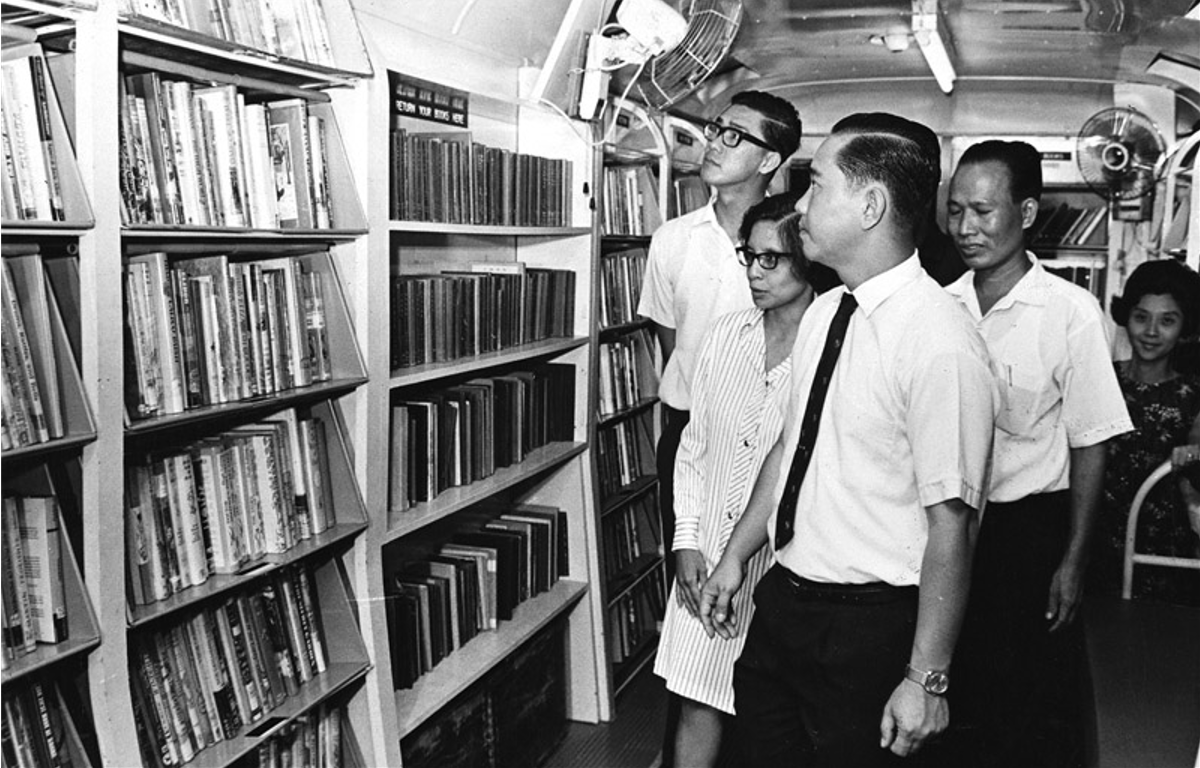

Hedwig Anuar, director of the National Library, shows Ho Kah Leong, Member of Parliament for Jurong, the interior of the mobile library trailer during the opening of the new mobile library service point at Taman Jurong, 1969. Collection of the National Library Singapore.

Hedwig Anuar, director of the National Library, shows Ho Kah Leong, Member of Parliament for Jurong, the interior of the mobile library trailer during the opening of the new mobile library service point at Taman Jurong, 1969. Collection of the National Library Singapore.After taking office, Anuar faced the closure of two of the four part-time branch libraries in Upper Serangoon and Yio Chu Kang when their premises were requisitioned by other government ministries. These closures affected the students who regularly used these branches and placed additional strain on the already overburdened library services at the National Library. In response, Anuar expedited the roll-out of the mobile library service to fill the void left by the closures and reach children in rural areas.10

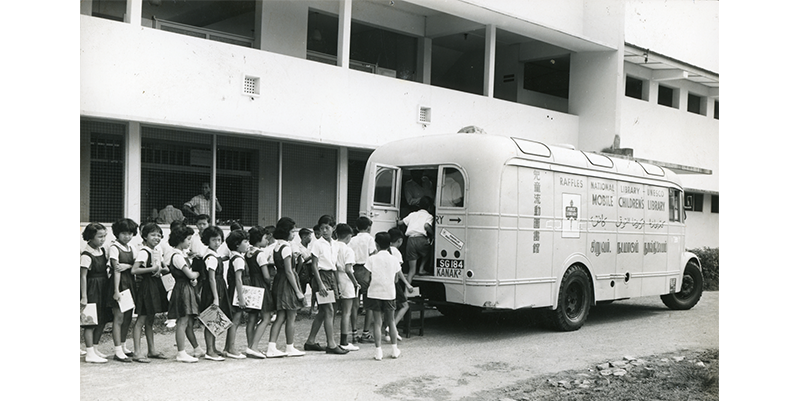

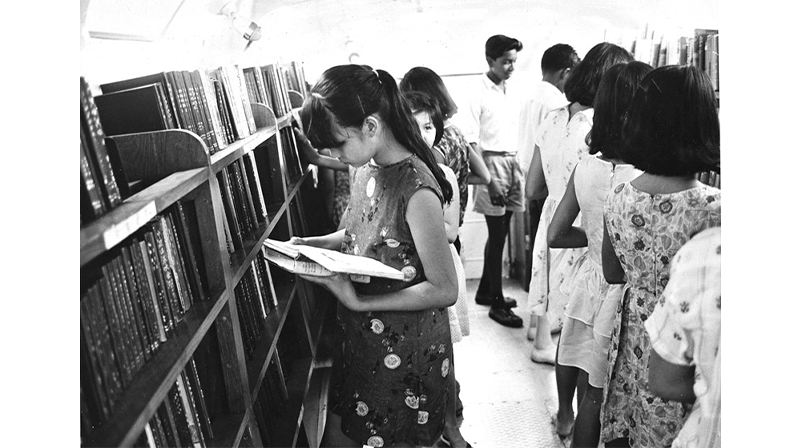

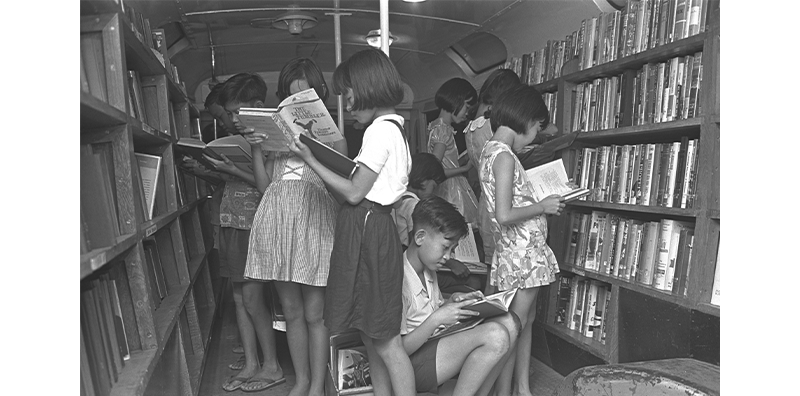

The mobile library’s maiden trip was to schools in the Naval Base area of Nee Soon. In the first two weeks, the van visited 37 schools in the outlying districts of Nee Soon, Sembawang, Jurong, Bukit Panjang and Tampines.11 The distinctive cream-coloured van, with the licence plate SG 184 and “Raffles National Library – UNESCO” painted on its livery, could hold up to 2,000 books in English, Malay, Chinese and Tamil.12

“The response to the mobile library is overwhelming,” said Anuar. “About 300 more children than the expected 2,000 have registered as members since it was started.” The library announced plans to conduct fortnightly visits and to gradually extend the service to other schools. By 1962, the mobile library service boasted a membership of 5,000.13

Retired educator Koh Boon Loong, who used the mobile library as a primary schoolboy in the 1960s, shared his memories in his 2011 oral history interview. “A mobile library would come to the school, and we were allowed to go up to borrow books, class by class… You could only borrow, I think, either one or two books. We read it for about 3 weeks and then we return[ed] it to the teacher [who] would collect it so that they could give it [back] as a batch to the mobile library when they come by.”14

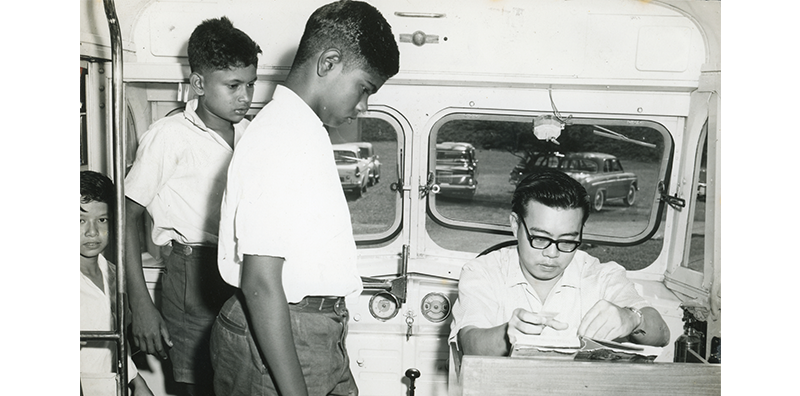

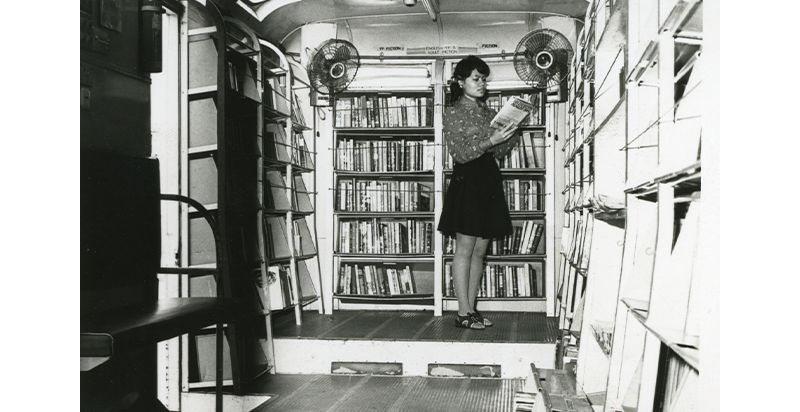

In his 2002 oral history interview, former senior library staff Douglas Koh said that because the mobile library van was small, a temporary counter was typically set up outside. The children would first return their books, then board the van to select new ones. After disembarking, they would have their books issued and date-stamped. Although part of the mobile library’s collection was routinely refreshed from the children’s section of the main library, its offerings were modest owing to the van’s limited capacity. Koh noted that this led to occasional grouses from frequent borrowers, who lamented that it was the “same same same collection”.15

Wong Heng, another former senior library staff, recalled that the van’s interior was stripped bare to accommodate custom-built shelves. These shelves were designed with an upward tilt to prevent books from sliding off during transit. The front section of the vehicle housed the driver’s seat and a small table for registration.16

Hiatus and Resumption of Service

Unfortunately, despite the popularity of the mobile library, the service was discontinued in 1962 due to a staff shortage and insufficient funds to replace the worn-out books.17 The arrival of Priscilla Taylor from New Zealand in April 1962 marked a turning point. Seconded as an advisor to the National Library under the Colombo Plan, Taylor assumed the directorship in August 1962 for two years. Having come from New Zealand, which had a robust mobile library system, Taylor was keen to revive the mobile library service during her tenure.18

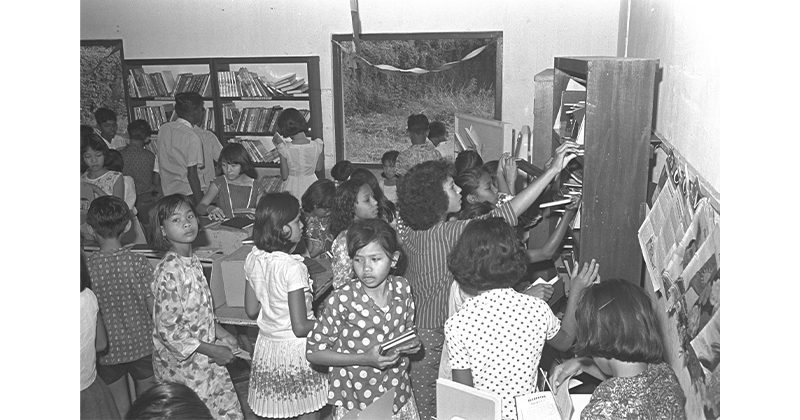

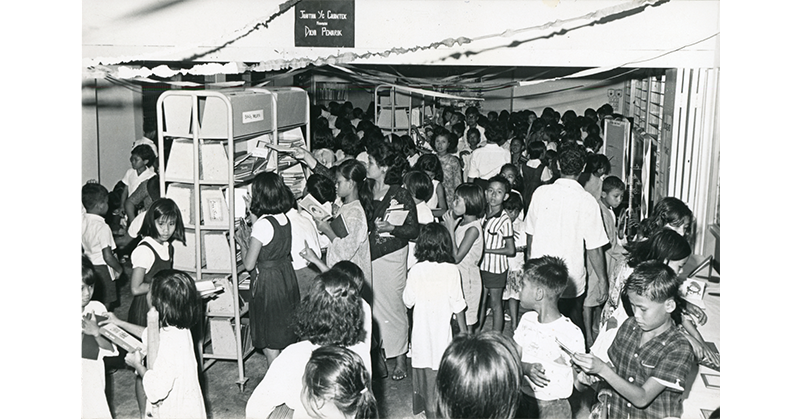

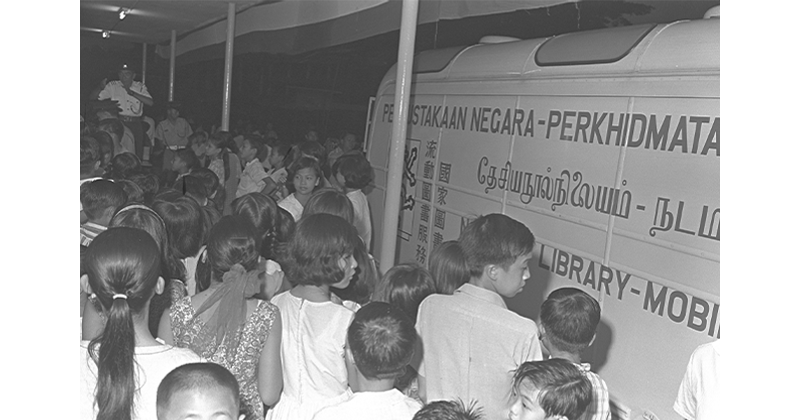

In October 1963, library staff conducted surveys of community centres, where many residents gathered, to assess their suitability as potential branch libraries or bookmobile stops. This evaluation led to the launch of a pilot bookmobile service in July 1964 that operated weekly for two hours in Tanjong Pagar and West Coast community centres. According to Anuar, Tanjong Pagar was selected for its dense urban population and, being Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew’s constituency, offered valuable publicity. West Coast, on the other hand, was chosen for its rural demographics. The public response was encouraging, with 877 children borrowing 16,081 books in just six months.19

Nee Soon was added in May 1965, quickly becoming the busiest of the three service points, followed by Bukit Panjang in February 1966. The mobile library service received a significant boost in September 1965 when the New Zealand government provided a book grant of NZ£10,000 under the Colombo Plan for the enhancement of the mobile library collection. This donation funded the purchase of 23,519 books in 1966 for the two unused book trailers, facilitating the service’s expansion.20

Chan Thye Seng, who received a Colombo Plan scholarship in 1962 to study librarianship in New Zealand, was given the task of expanding the mobile library service after returning to Singapore in 1963. Having seen rural library service firsthand, Chan spearheaded the development and growth of the service, becoming synonymous with Singapore’s mobile library efforts in later years. He subsequently headed the Home Reading Division which managed the Library Extension Services.21

By 1967, the mobile library service had expanded rapidly, growing from four to 10 service points. The new locations were community centres in Chong Pang, Kaki Bukit, Kampong Tengah, Bukit Timah, Changi 10 milestone and Paya Lebar. The 10 mobile library service points and the two part-time branch libraries at Joo Chiat and Siglap accounted for nearly half of all children’s book loans.22

To aid expansion, one of the two mobile library trailers, originally purchased in 1959, was finally deployed in 1967. An open garage was also constructed in the staff carpark at the National Library building to house the two trailers, which were previously stationed at the Kallang Depot of the Public Works Department (PWD).23

The mobile library service reached its peak between 1969 and 1973, operating 12 service points. In 1972, a mobile library bus was added to the fleet, and in December 1973, the Library Extension Services section moved from Stamford Road to the new Toa Payoh Branch Library. The mobile service was also streamlined, and several service points were relocated.24

The library staff enjoyed interacting with users of the mobile library service. “All the people who worked on the mobile library used to say they enjoyed it because the children would be so excited at having books brought to their doorstep,” said Anuar. The mobile service, being a novelty, was popular with residents. “[F]or a lot of the rural people, it was the first time that they ever had access to books because they couldn’t really afford to buy books. So I think that was a big thing.” A Straits Times article in 1979 recounted that “hordes of children [would] start gathering as the time approaches and there [would be] mad rush to be at the head of the queue when the [mobile library] van arrives”.25

Mobile Library Operations

In contrast to the earlier mobile library service that toured schools, the revived mobile library service operated weekly visits to community centres, mostly in the afternoon or evening.26

These visits were typically staffed by a lean team of three or four comprising a driver, a library officer and one or two clerical assistants. Back then, the road system was less developed, and travelling time and distances were much longer. To maximise efficiency and save on fuel, routes had to be carefully planned to incorporate two locations in one trip. For instance, if a visit to Bukit Panjang was made, a stop would be made at Bukit Timah too.27

Staff also had to maintain a large rotating stock of books, both fiction and non-fiction for children, young people and adults, in the four official languages, as well as materials for readers with limited literacy.28

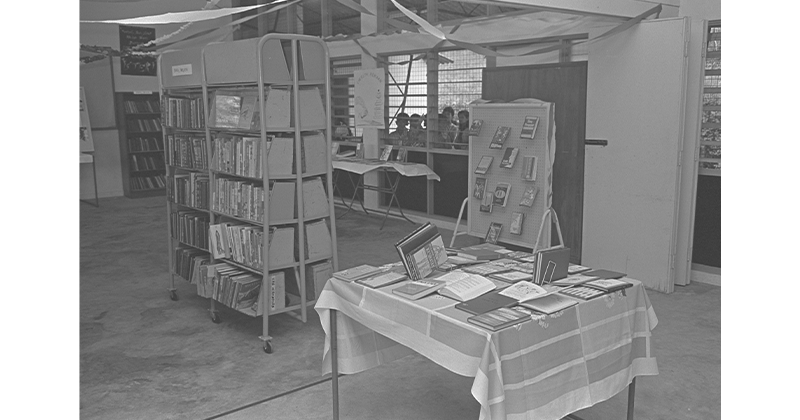

To avoid long queues and slow service at each service point, library staff would unload the books from the mobile library van and display them on mobile racks or book trays in a space provided by the community centre. A temporary counter would be set up to record loans and returns. As these visits were weekly, children frequently found themselves borrowing books that their peers have returned. Adult borrowers, being fewer in number, continued to board the van for book selection.29

As the mobile library service developed, storytelling programmes were added to the offerings.30 To boost publicity, the service was promoted through school talks, and also over radio and television.31

Rain or Shine

Operating a mobile library service presented unique challenges. At times, the service had to be scaled back or suspended due to staff shortage, driver shortage, or vehicle breakdown.32

Chan Thye Seng, who led the expansion of the mobile library service, recalled the various difficulties that they had to overcome. “On one occasion, three out of the four male serving clerical assistants were called up for reservist training. On another, three of the four mobile library drivers vacated office.”33

The mobile service was also at the mercy of inclement weather. “Once there was an island-wide flood in 1969, and the stalled vehicle had to be towed back from the outlying area to the PWD workshop at Kallang,” Chan recalled. “There was quite a queue and long wait for repairs and servicing, as priority was given to ambulances and police patrol cars.” Instead of disappointing the people and children who would wait expectantly for the arrival of the van, Chan said that staff would hire two to three taxis to transport the books to the location. “Rain or shine, the service had to continue!”34

Another problem was getting drivers for the trailers. Chan recalled: “Although we had four drivers and one van, I had to get these drivers on the road to drive these trailers and the drivers refused to drive. They said because these are heavy vehicles, we are general purpose drivers. We need certain extra allowances, and we also need to be trained. So, I arranged for the PWD to train up the drivers to drive the heavy vehicles.” Their salaries were also increased.35

Phasing Out Mobile Libraries

In 1973, because of government efforts to curb inflation and to manage the global energy crisis, the National Library was tasked with evaluating the efficiency of its mobile library service. The goal was to potentially reduce or relocate the existing 12 service points. The relocation of the Library Extension Services section to Toa Payoh Branch Library also provided an opportunity to streamline mobile library operations. Consequently, in 1974, three service points – Pasir Panjang, Changi 10 milestone and Serangoon Gardens – were shut down.36

As families in rural areas were increasingly resettled in new towns, the need for mobile libraries declined. While these had once been vital, they were less cost-effective and offered readers a smaller selection of materials than permanent branch libraries. In 1979, a fulltime planning officer was appointed to revise the library development plan. The aim was to phase out mobile and part-time libraries, and replace them with fulltime branch libraries. The new plan envisioned eight branch libraries within the next 11 years in the housing estates of Ang Mo Kio, Jurong, Bedok, Geylang East, Hougang, Tampines, Nee Soon and Woodlands.37

Under this strategic shift, no new mobile service points were added except for Ang Mo Kio where a mobile library service point was established to provide interim services until the completion of the Ang Mo Kio Branch Library. On 14 January 1991, the mobile library service, along with its six remaining service points at Choa Chu Kang, Nee Soon, Punggol, Changkat, Tanjong Pagar and Woodlands, ceased operations after 26 years of service.38

Molly the Mobile Library

The idea of a mobile library service was too good to be mothballed forever though. On 3 April 2008, the National Library Board (NLB) launched Molly, a new mobile library service, to better reach disadvantaged and underserved communities. At the opening ceremony held at Pathlight School, Minister for Community Development, Youth and Sports Vivian Balakrishnan said: “The challenge today is not the physical availability of libraries, but rather, reaching out and making sure that people who can benefit from the access to books know about it and are given the access to it.”39

Molly, retrofitted from a former SBS transit bus, was installed with modern library technology such as borrowing stations and e-kiosks for onboard transactions. It was the world’s first fully wireless-enabled mobile library bus where transactions could be carried out digitally. The bus, which carried approximately 3,000 books, made visits to special-education schools, homes and orphanages, welfare homes and volunteer welfare organisations. Beyond lending books, Molly offered storytelling sessions and user education workshops, and participated in community outreach events. In its first year of operations, Molly served 45,114 visitors from 17 special needs schools, 16 homes and orphanages and 30 primary schools. In 2011, the Molly bus was retired and replaced the following year with an upgraded model that had iPads with e-books and a wheelchair ramp.40

With donations from the Kwan Im Thong Hood Cho Temple, the service expanded in May 2014 with two mini mobile library vans, known as Mini Mollys. These scaled-down versions of the Molly bus can hold up to 1,500 books and navigate narrow driveways and parking lots in small housing estates. They primarily serve kindergartens and childcare centres in housing estates as well as welfare homes that could not be reached by the bigger Molly. During these visits, children’s activities such as storytelling, arts and craft workshops and sing-along sessions are also conducted. Each year, Mini Mollys bring books and library programmes to 48,000 children from 160 preschools.41

A storytelling session in Mini Molly, 2014. Collection of the National Library Board.

A storytelling session in Mini Molly, 2014. Collection of the National Library Board. In September 2016, a new vehicle known as “Big Molly”, also sponsored by the temple, replaced the 2012 Molly bus which was decommissioned. This newer version carries up to 3,000 books and features enhanced accessibility, including a hydraulic wheelchair lift to serve wheelchair users and book stations placed at a lower height for children to borrow and return books on their own. Today, Big Molly visits special needs schools, homes and orphanages, welfare homes, lower-income groups and housing estates. It also conducts weekend outreach events in residential estates across Singapore.42

The interior of Big Molly, 2016. Collection of the National Library Board.

The interior of Big Molly, 2016. Collection of the National Library Board.

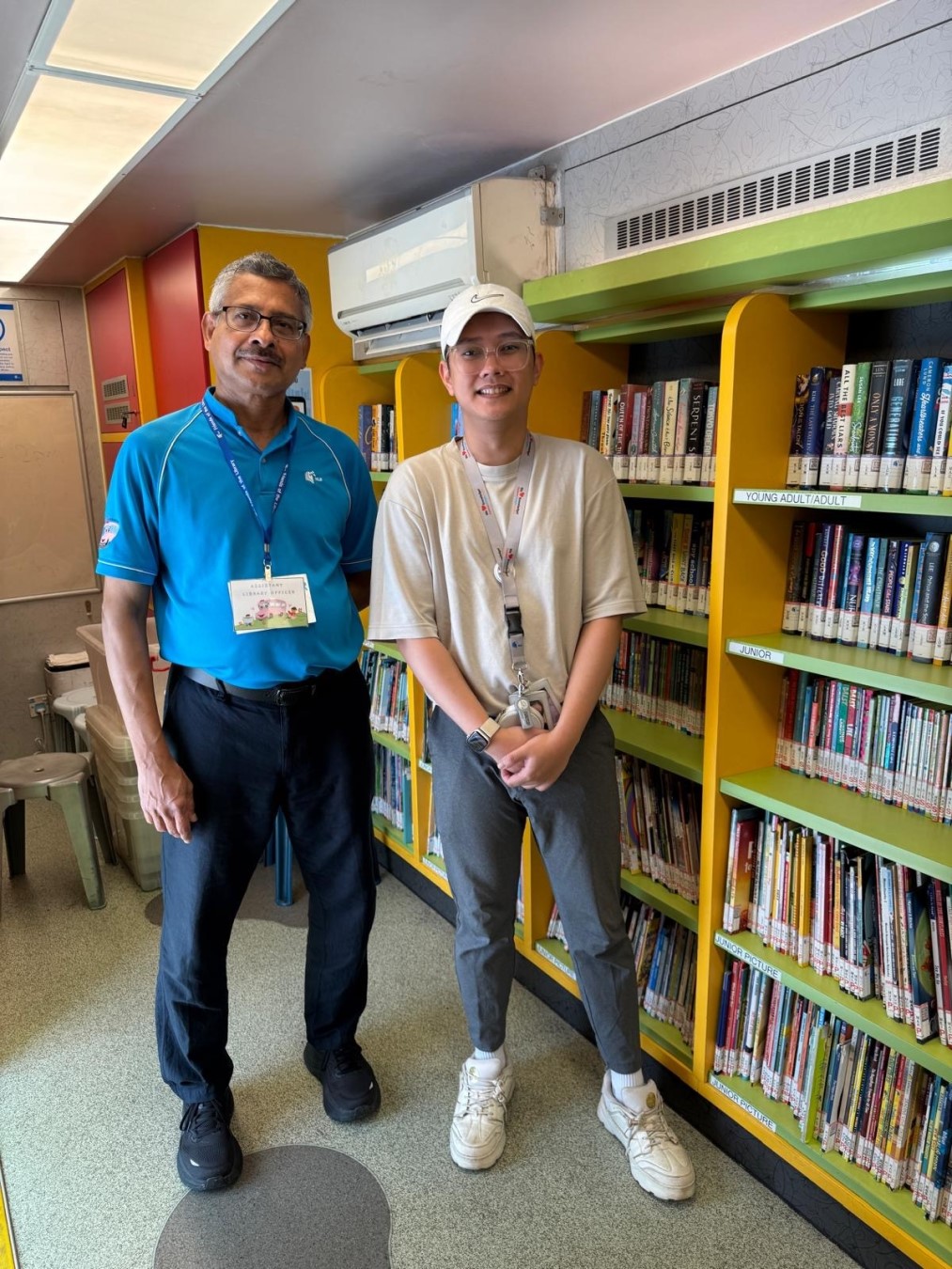

Assistant Library Officer Mohan M. (left) and Library Officer Wesley Agustian on duty at Big Molly, Marine Terrace, 29 March 2025. Photo by Jimmy Yap.

Assistant Library Officer Mohan M. (left) and Library Officer Wesley Agustian on duty at Big Molly, Marine Terrace, 29 March 2025. Photo by Jimmy Yap.  Gracie Lee is a Senior Librarian with the National Library Singapore. She enjoys uncovering and sharing the stories behind Singapore’s printed heritage.

Gracie Lee is a Senior Librarian with the National Library Singapore. She enjoys uncovering and sharing the stories behind Singapore’s printed heritage. Notes

-

“Exposition a ‘Mirror,’ Says the Governor,” Straits Times, 7 February 1959, 9. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Library Tells It in Colour,” Singapore Standard, 18 January 1959, 3; “Mock Election at the Exposition,” Singapore Standard, 3 February 1959, 6; “Mobile Libraries Await Staff,” Sunday Times, 29 March 1959, 4 (From NewspaperSG); Department of Information Services, Singapore, Singapore Constitution Exposition, Jan–Feb, 1959: Souvenir Number (Singapore: Department of Information Services, 1959), 33–57. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RCLOS 959.51 SIN) ↩

-

“Expansion of S’pore Library Services,” Sunday Standard, 23 March 1958, 3; “Free Library,” Straits Times, 14 September 1957, 8. (From NewspaperSG); ↩

-

“New Library Will Still Be Raffles’s,” Straits Times, 1 August 1956, 8; “National Library for S’pore,” Singapore Standard, 1 August 1956, 2. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Chistine Diemer, “They All Want To Read,” Sunday Standard, 1 June 1958, 4; “National Library to Expand Asian Section,” Singapore Free Press, 8 September 1959, 3 (From NewspaperSG); National Library Singapore, Annual Report 1966 (Singapore: National Library, 1968), 10. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RCLOS 027.55957 RLSAR); Fong Sip Chee, “Inauguration of the National Library’s Mobile Library Service,” speech, Chong Pang Community Centre, 27 January 1967, transcript, Ministry of Culture. (From National Archives of Singapore record no. NL 266-62 Vol 1). [The speech is found on pp. 160–61 of the flipviewer.] ↩

-

“Value of the Public Library,” Singapore Standard, 22 January 1958, 8; “Three Mobile Libraries for Outlying Areas,” Straits Times, 8 January 1960, 4. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

K.K. Seet, A Place for the People (Singapore: Times Books International, 1983), 120–21. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 027.55957 SEE); National Library Board, Singapore, Report: 5th December 1960 to 30th September 1963 (Singapore: Government Printing Office, 1963), 4–5. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RCLOS 027.55957 SIN); “Mobile Libraries Await Staff”; “Rush to Join National Library,” Singapore Free Press, 11 April 1958, 5. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Diemer, “They All Want To Read”; “Upsurge in Youth’s Love of Reading,” Singapore Free Press, 14 July 1959, 10. (From NewspaperSG); Seet, A Place for the People, 120; Singapore Department of Statistics, Report on the Census of Population 1957 (Singapore: Government Printing Office, 1964), 50. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RCLOS 312.095951 SIN) ↩

-

Seet, A Place for the People, 120–21; “Library Service on Wheels,” Straits Times, 5 September 1960, 7. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Seet, A Place for the People, 120–21; “New Mobile Library Service to Schools,” Singapore Free Press, 5 September 1960, 11. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“New Mobile Library Service to Schools”; Lydia Aroozoo, “The Reading Habit at Your Doorstep: Library on Wheels Gets a Big Welcome at the Rural Schools,” Singapore Free Press, 21 September 1960, 7. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Aroozoo, “The Reading Habit at Your Doorstep”; National Library Board, Moments in Time: Memories of the National Library (Singapore: National Library Board Singapore, 2004), 23. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 027.5095957 MOM-[LIB]) ↩

-

“New Mobile Library Service to Schools”; Aroozoo, “The Reading Habit at Your Doorstep”; Hedwig Anuar, “Singapore’s National Library,” Straits Times Annual, 1 January 1962, 58-59. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Koh Boon Long, oral history interview by Jason Lim, 19 August 2011, Reel/Disc 3 of 36, National Archives of Singapore (accession no. 003625), 00:46. ↩

-

Douglas Koh Bee Chuan, oral history interview by Jason Lim, 31 October 2002, MP3 audio, Reel/Disc 5 of 10, National Archives of Singapore (accession no. 002368), 17:13. ↩

-

Wong Heng, oral history interview by Jason Lim, 12 November 1999, transcript and MP3 audio, Reel/Disc 6 of 13, National Archives of Singapore (accession no. 001702), 71–72. ↩

-

National Library Board Singapore, Report: 5th December 1960 to 30th September 1963, 5, Appendix VII. ↩

-

“Miss Taylor’s 3 Hopes for S’pore Library,” Straits Times, 1 August 1964, 13. (From NewspaperSG); Hedwig Elizabeth Anuar née Aroozoo, oral history interview by Jesley Chua Chee Huan, 16 October 1998, transcript and MP3 audio, Reel/Disc 28 of 44, National Archives of Singapore (accession no. 002036), 356. ↩

-

Hedwig Elizabeth Anuar née Aroozoo, oral history interview, 16 October 1998, Reel/Disc 28 of 44, 353; National Library Board Singapore, Report for the Period from 1 October 1963 to 30 September 1965 (Singapore: National Library Board, n.d.), 7. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RCLOS 027.55957 RLSAR); National Library Singapore, Annual Report 1964 (Singapore: National Library, 1967), 12. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RCLOS 027.55957 RLSAR) ↩

-

National Library Singapore, Annual Report 1963–1965, 7; National Library Singapore, Annual Report 1965 (Singapore: National Library, 1967), 11. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RCLOS 027.55957 RLSAR); National Library Singapore, Annual Report 1966, 2, 9; Fong, “Inauguration of the National Library’s Mobile Library Service.” ↩

-

National Library Singapore, Annual Report 1971, (Singapore: National Library, 1973), 28. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RCLOS 027.55957 RLSAR); ↩

-

National Library Singapore, Annual Report 1967 (Singapore: National Library, 1969), 14. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RCLOS 027.55957 RLSAR) ↩

-

National Library Singapore, Annual Report 1967, 2, 14. ↩

-

National Library Singapore, Annual Report 1969 (Singapore: National Library, 1970), 3 (From National Library Singapore, call no. RCLOS 027.55957 RLSAR); National Library Singapore, Annual Report 1972 (Singapore: National Library, 1973), 2, 9. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RCLOS 027.55957 RLSAR); National Library Singapore, Annual Report 1973 (Singapore: National Library, 1974), 12. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RCLOS 027.55957 RLSAR); Wong Heng, oral history interview, 12 November 1999, Reel/Disc 6 of 13, 70. ↩

-

Hedwig Elizabeth Anuar née Aroozoo, oral history interview, 16 October 1998, Reel/Disc 28 of 44, 355; Lee Geok Boi, “Mad Rush When the Library Van Comes,” Straits Times, 14 July 1979, 1. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

National Library Board Singapore, Library Extension Section (Singapore: National Library Board, 1966). (From National Library Singapore, call no. RCLOS NC25); Guide to the National Library’s Part-time Branch and Mobile Libraries (Singapore: National Library 1978), 6–8. (From PublicationSG) ↩

-

Hedwig Elizabeth Anuar née Aroozoo, oral history interview, 16 October 1998, Reel/Disc 28 of 44, 355; Chan Thye Seng, oral history interview, 10 May 2000, Reel/Disc 8 of 15, 91. ↩

-

Hedwig Elizabeth Anuar née Aroozoo, oral history interview, 16 October 1998, Reel/Disc 28 of 44, 356; Chan Thye Seng, oral history interview, 10 May 2000, Reel/Disc 8 of 15,91. ↩

-

Chan Thye Seng, oral history interview, 10 May 2000, Reel/Disc 8 of 15, 91, 94; Hedwig Elizabeth Anuar née Aroozoo, oral history interview, 16 October 1998, Reel/Disc 28 of 44, 352. ↩

-

National Library Singapore, Report for the Period April 1978 – March 1979 (Singapore: National Library, 1979), 11. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RCLOS 027.55957 RLSAR) ↩

-

Hedwig Elizabeth Anuar née Aroozoo, interview, 16 October 1998, Reel/Disc 28 of 44, 357–58; National Library Singapore, Annual Report 1967, 19; National Library Singapore, Annual Report 1972, 18. ↩

-

National Library Singapore, Annual Report 1967, 14; National Library Singapore, Annual Report 1969, 8; National Library Singapore, Annual Report 1970 (Singapore: National Library Singapore, 1971), 7. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RCLOS 027.55957 RLSAR); National Library Singapore, Report for the Period January 1975 – March 1976 (Singapore: National Library, 1976), 8. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RCLOS 027.55957 RLSAR) ↩

-

Chan Thye Seng, “Speaking of… Mobile Memories,” Singapore Libraries Bulletin 11, no. 4 (2001): 2–3. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 020.5 SLB-[LIB]) ↩

-

Chan “Speaking of… Mobile Memories,” 2–3. ↩

-

Chan Thye Seng, interview, 10 May 2000, Reel/Disc 8 of 15, 93; “New Groupings and Pay for Drivers,” New Nation, 20 September 1972, 2. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

National Library Singapore, Annual Report 1973, 21; National Library Singapore, Annual Report 1974 (Singapore: National Library, 1975), 13–14. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RCLOS 027.55957 RLSAR) ↩

-

National Library Singapore, Report for the Period April 1979 – March 1980 (Singapore: National Library, 1980), 14–15. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RCLOS 027.55957 RLSAR); National Library Singapore, Report for the Period April 1980 – March 1981 (Singapore: National Library, 1981), 12. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RCLOS 027.55957 RLSAR); “Mobile Library Services to Cease,” Straits Times, 6 April 1981, 26. (From NewspaperSG); Ng Cheng Onn, oral history interview by Jason Lim, 13 April 2000, transcript and MP3 audio, Reel/Disc 4 of 17, National Archives of Singapore (accession no. 002274), 41. ↩

-

National Library Singapore, Report for the Period April 1980 – March 1981, 12; National Library Singapore, Report for the Period FY 81 and FY82 (Singapore: Printed by the Government Printing Office, n.d.), 9. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RCLOS 027.55957 RLSAR); National Library Singapore, Report for the Period April 1990 – March 1991 (Singapore: National Library, 1991), 5, 48. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RCLOS 027.55957 RLSAR); National Library Singapore, Report for the period April 1991 – March 1992 (Singapore: National Library, 1992), 49. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RCLOS 027.55957 RLSAR) ↩

-

National Library Board, Molly’s Memories, Milestones and Moments: Celebrating Mobile Library Services in Singapore, 6, 33. ↩

-

National Library Board, Molly’s Memories, Milestones and Moments: Celebrating Mobile Library Services in Singapore, 32–55; Leslie Kay Lim, “Library on Wheels Moves with the Times,” Straits Times, 25 February 2012, B4; Benson Ang, “Services on Wheels,” Straits Times, 5 April 2015, 3. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

National Library Board, National Library Board Annual Report FY 2014/2015 (Singapore: National Library Board, 2015), https://www.nlb.gov.sg/main/-/media/NLBMedia/Documents/About-Us/Press-Room-Publication/Annual-Reports/AR-2014-15.pdf; “About Molly Mobile Library,” National Library Board, accessed 19 March 2025, https://www.nlb.gov.sg/main/visit-us/public-libraries-singapore/mobile-library-molly; Amelia Teng, “Two More Mobile Libraries Hit the Road,” Straits Times, 9 May 2014, 11; Ariel Lim, “‘Mini-Molly’ Mobile Libraries a Runaway Hit,” Straits Times, 11 June 2015, 6. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

National Library Board, National Library Board Annual Report FY 2016/2017 (Singapore: National Library Board, 2017), https://www.nlb.gov.sg/main/-/media/NLBMedia/Documents/About-Us/Press-Room-Publication/Annual-Reports/AR-2016-17.pdf; National Library Board, National Library Board Annual Report FY 2023/2024 (Singapore: National Library Board, 2024), https://www.nlb.gov.sg/main/-/media/NLBMedia/Documents/About-Us/Press-Room-Publication/Annual-Reports/NLB_Annual_Report_2023_2024.pdf; “About Molly Mobile Library,” National Library Board, accessed 19 March 2025, https://www.nlb.gov.sg/main/visit-us/public-libraries-singapore/mobile-library-molly; “What’s On,” National Library Board, accessed 19 March 2025, https://www.nlb.gov.sg/main/whats-on/events; Nadia Chevroulet, “Chapter 3 for Molly, the Library on Wheels,” Straits Times, 23 September 2016, 3; Katelyn Woodworth, “Miss Molly Gets a Makeover,” Straits Times, 4 October 2016, 4. (From NewspaperSG) ↩