Lady in Red: The Former National Library on Stamford Road

Beyond being a mere repository of books, the library on Stamford Road was a place for acquiring knowledge, making memories and creating friendships.

By Lim Tin Seng

The former National Library building on Stamford Road, which opened in 1960, became a beloved landmark in the area thanks to its striking red-brick facade and distinctive modern architecture. This photo essay revisits the history and legacy of the building.

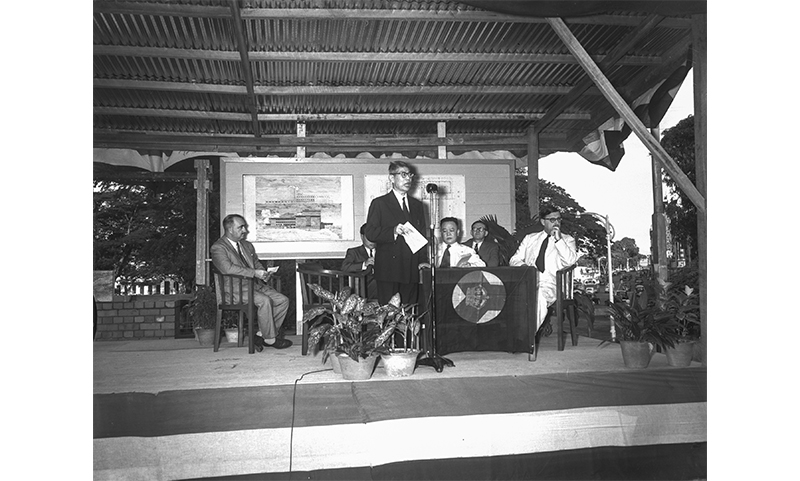

Unveiling a Literary Haven

The National Library on Stamford Road was officially inaugurated on 12 November 1960 by Yang di-Pertuan Negara (Head of State) Yusof Ishak. In his speech, he said the new library would “serve the needs of nation-building and its departments of knowledge learning, and technology embraced a wide field”. He encouraged people to visit the library noting that it “is available for free use of all citizens of Singapore, and it is financed entirely from public funds. I call upon the people of Singapore to use this National Library of theirs as fully as possible”.1 It was reported that “[i]ncessant hordes of people [were] milling about the library grounds on that auspicious day”, all of them curious to see the new library.2

A Philanthropist’s Donation

In 1953, businessman and philanthropist Lee Kong Chian donated $375,000 towards the building of the library. His contribution, which came with the stipulation that the library remain public and free for all, helped fund the construction on a site previously occupied by the St John’s Ambulance Headquarters and British Council Hall. Lee himself laid the foundation stone on 16 August 1957 and the total cost to construct the National Library – including land, construction and furnishings – was estimated at $2.5 million.3 (Prior to this, the library was located in the building that is now the National Museum of Singapore.)

A Symphony in Red Brick

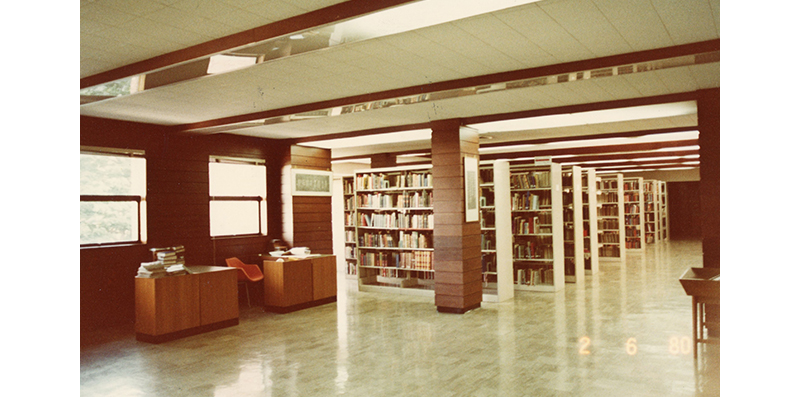

At its opening, the National Library featured a distinctive T-shaped block layout, spanning approximately 101,500 sq ft (9,430 sq m). Designed by Lionel Bintley of the Public Works Department, the building housed a wide range of facilities, including a lending library, a reference library, study spaces, lecture halls, conference rooms, storage areas for books, administrative offices, technical service workrooms and an open-air courtyard.

Externally, the structure was clad in striking red brick that became the hallmark of its architectural identity. While some admired the library’s unique aesthetic, which was said to reflect the red-brick era of 1950s British architecture, others criticised it for appearing discordant with adjacent buildings like the National Museum. Architects used terms such as “a monstrous monument”, “haphazard”, “clumsy”, “heavy” and “lacks basic discipline” to describe the building.4

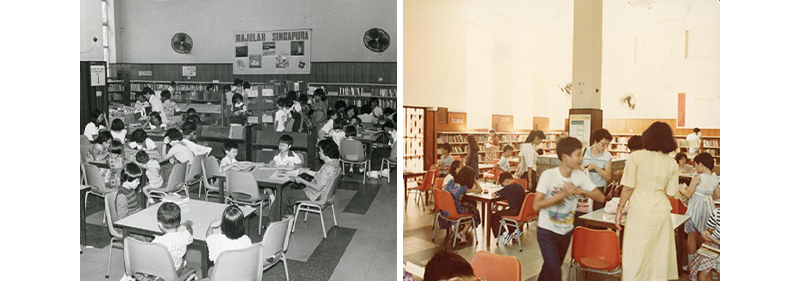

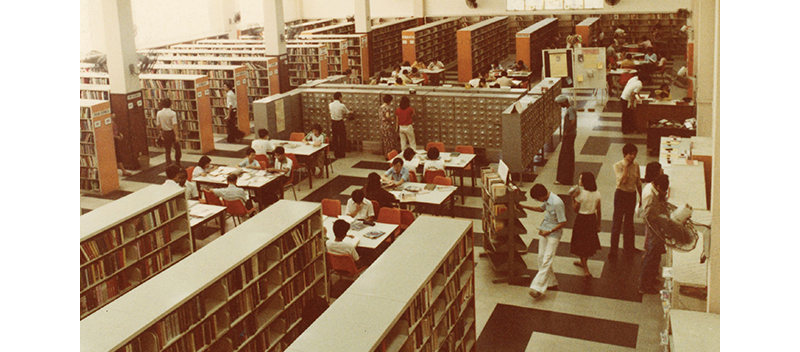

A Place for All

The National Library offered a wide array of collections and services. The public lending library included separate sections for adult and children’s books as well as facilities for activities, while the reference library housed the South East Asia Collection.

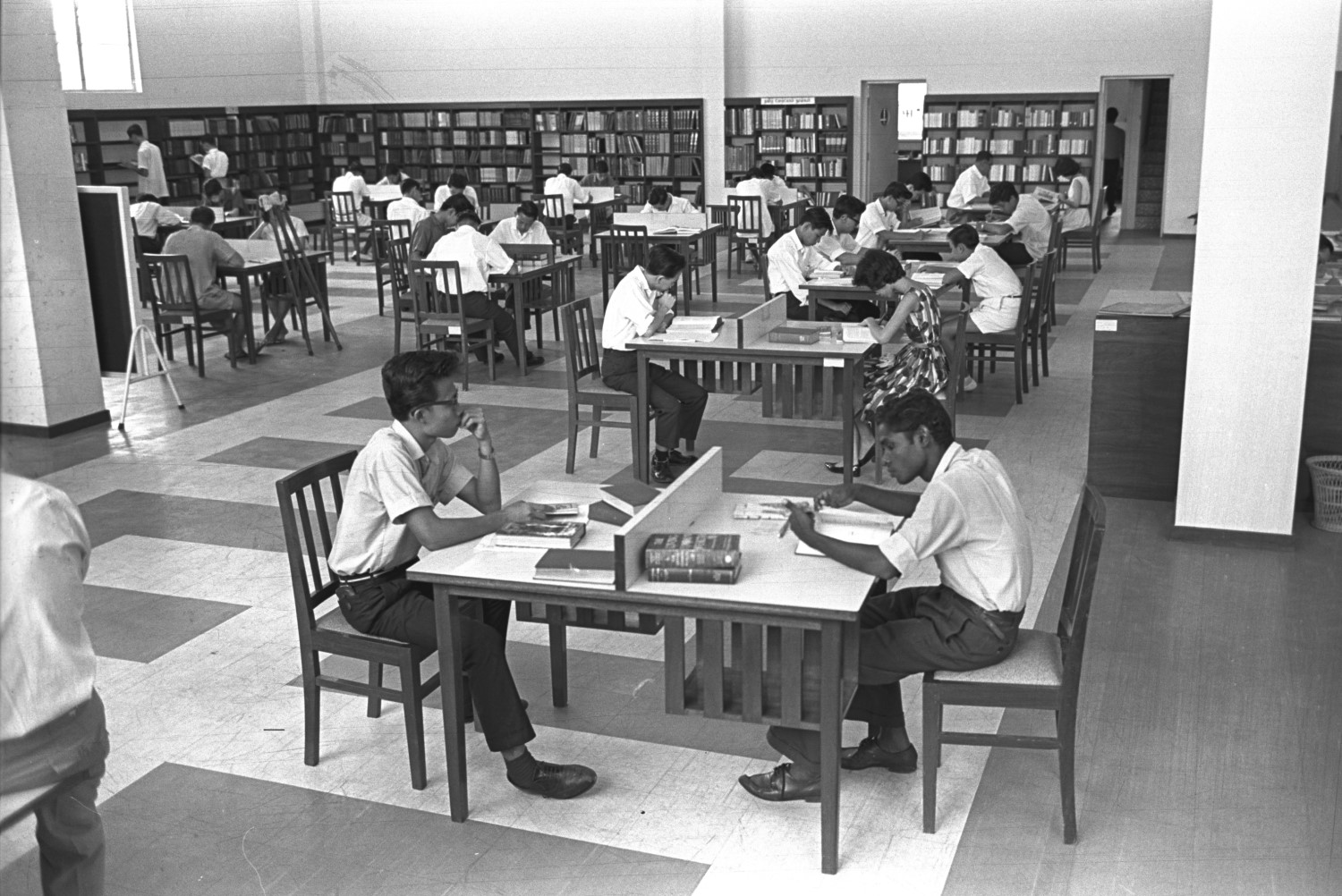

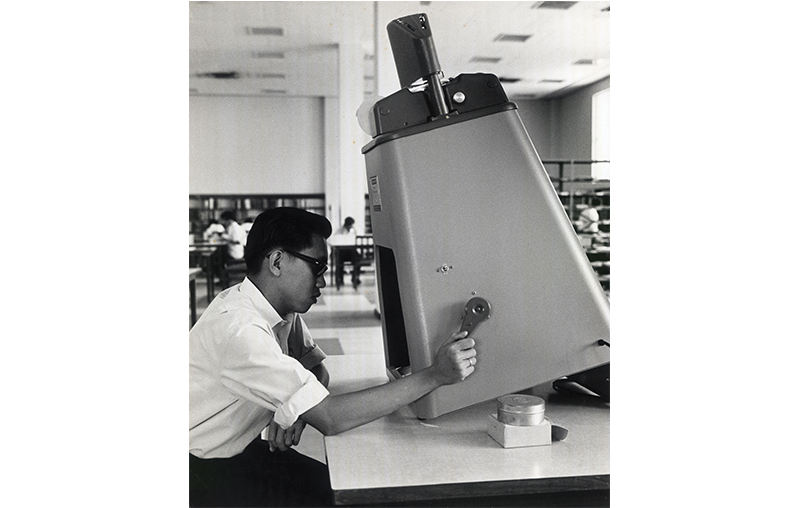

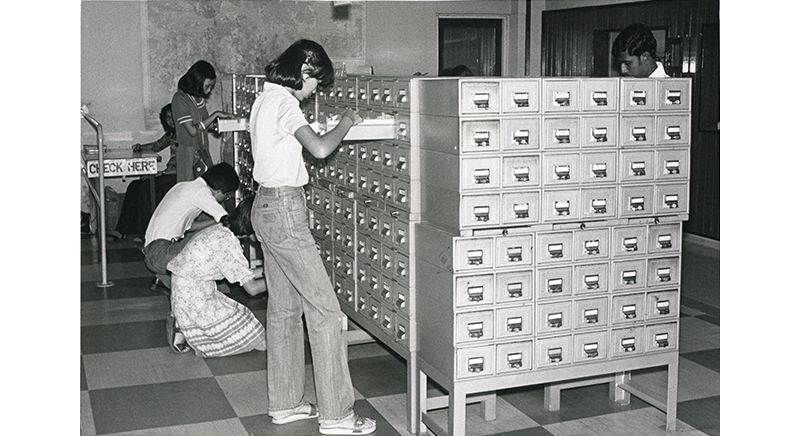

The Reference Room at the National Library, 1964. Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

The Reference Room at the National Library, 1964. Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

With a seating capacity of more than 400, visitors also had access to equipment like microfilm readers to read old newspapers. Over time, the library’s facilities were upgraded. Air-conditioning was added and the collections also expanded significantly, particularly in the Chinese, Malay and Tamil sections, and from materials gifted by donors.5

A Treasure Trove

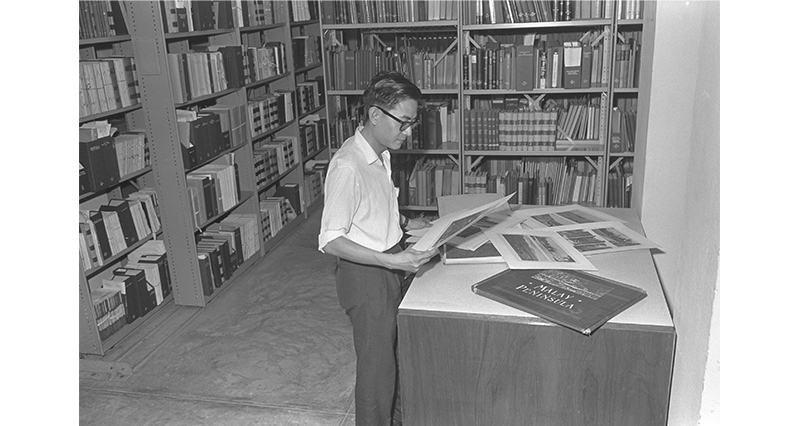

On 28 August 1964, the South East Asia Room at the National Library opened as a dedicated space “devoted solely to the study of South East Asia”. This specialised room housed a large collection of materials on Singapore and the region that the library had accumulated since its establishment in 1837.6

Minister for Culture S. Rajaratnam, who officiated its opening, described the room as “beyond price” and “absolutely unattainable from any other source”. “From the closed stacks at the back of the building our librarians have now brought out this famous collection,” he said in his speech. “In this room this afternoon you will be able to see copies of letters written by Raffles, the first newspaper published in Singapore, or you can check reports on land costs a hundred years ago, or complaints on the behaviour of some of the civil servants of the time.”7

The materials included the 10,000-volume Ya Yin Kwan Collection covering diverse subjects with a focus on the Chinese in Southeast Asia, Reinhold Rost’s 970-volume philological and scientific collection featuring Eastern languages and Malay Archipelago studies, the 1,000-volume Gibson-Hill Collection on Malayan flora, fauna, travel histories and arts, and James Richardson Logan’s 1,250-strong collection of ethnography and philological works on the Malay Archipelago, among others. Today, these collections form part of the National Library’s National Collection.8

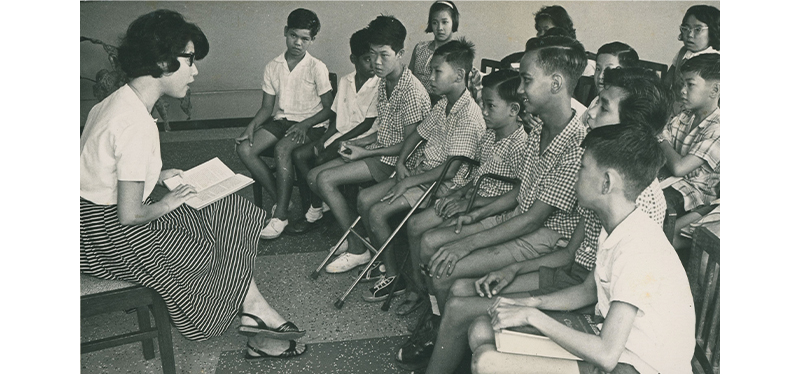

Nurturing Minds and Fostering Community Spirit

The National Library also served as a vibrant community hub (and still does) to engage people from all walks of life. It hosted library tours, concerts, drama performances, storytelling sessions, book discussions, exhibitions, reading campaigns, meet-the-author sessions, book festivals and talks. These initiatives aimed to promote reading and learning while fostering a deep connection with the public.

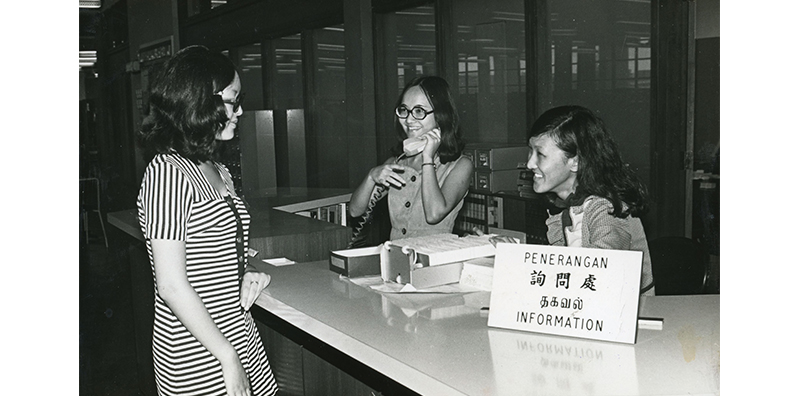

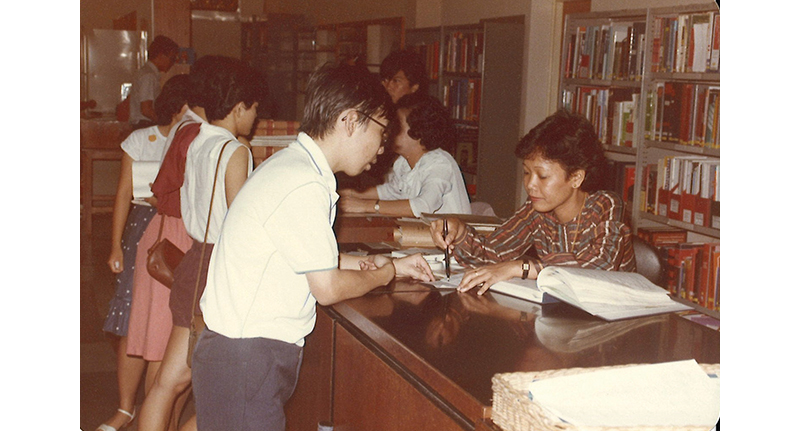

Unsung Heroes of Stamford Road

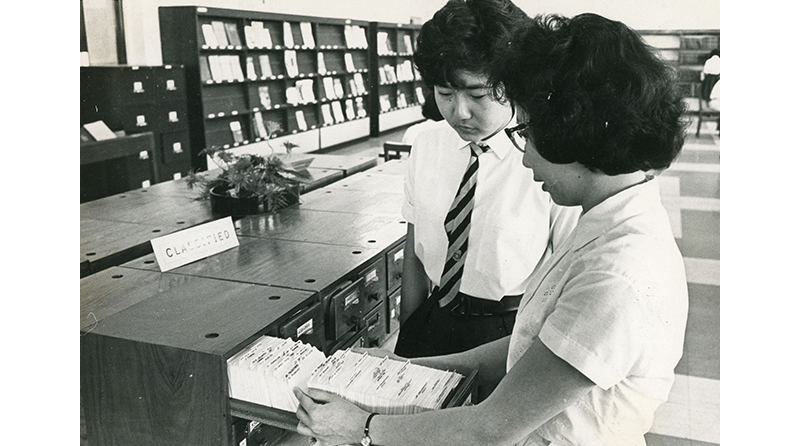

The National Library owed much of its success and impact to its staff. At the reference counters, the staff addressed public enquiries, providing guidance and expertise. In later years, the library would accept queries by mail and the telephone, and subsequently email.

Behind the scenes, countless library staff handled essential duties such as acquiring new materials, cataloguing, compiling the national bibliography, and undertaking conservation and preservation work like microfilming and book repairs.

A New Chapter

In March 1997, the National Library underwent a six-month extensive makeover costing $2.6 million. When it reopened in October that year, its facade had been updated with glass partitions and its interior replaced with carpeted floors.

A new Singapore Resource Centre was set up to replace the South East Asia Room, while the lending library was renamed the Central Community Library and furnished with a new information counter as well as new shelves and study tables.

The long snaking queues became a thing of the past as self-check machines and an automated bookdrop allowed patrons to borrow and return books with greater convenience. Computer stations with Internet access were also added to aid the discovery of new information and library materials.9

The 300-square-metre courtyard of the National Library also underwent a transformation. After upgrading works, the courtyard was repurposed as a public space to “promote the library as a vibrant place and as a venue for creative expressions like poetry, readings, drama or dance performances, or forum discussions on an art topic,” said Lim Siew Kim, deputy director of the National Reference Library. The addition of a fountain and a café enhanced the ambience and further improved library user experience.10

From Stamford Road to Victoria Street

In 1998, it was announced that the National Library would be demolished to make way for the Singapore Management University and the construction of Fort Canning Tunnel. The Preservation of Monuments Board (now Preservation of Sites and Monuments), which evaluated the building, found that it did not “possess sufficient merit to be accorded the status of a gazetted national monument”.

The decision sparked public calls to preserve the building. However, the demolition plan went ahead, citing the need for better land use in the area and to alleviate traffic congestion. The National Library closed its doors on 1 April 2004 before reopening on 12 November 2005 at its current state-of-the-art premises on Victoria Street.11

Although the National Library building on Stamford Road no longer exists, its entrance pillars are preserved within the grounds of the Singapore Management University. Some of the red bricks were salvaged and utilised for the construction of the wall of the garden at the Basement 1 Central Public Library in the new building. The St Andrew’s Cross – a geometric floor pattern consisting of four adjoining crosses – that used to adorn the floor of the entrance at the Stamford Road building was moved to a space outside the new building.12

Bricks from the former National Library were used for the wall in the garden of the Central Public Library, 2025. The bronze sculpture of the girl reading is by Singaporean sculptor Chong Fah Cheong. Photo by Jimmy Yap.

Bricks from the former National Library were used for the wall in the garden of the Central Public Library, 2025. The bronze sculpture of the girl reading is by Singaporean sculptor Chong Fah Cheong. Photo by Jimmy Yap.Its literary heritage lives on in the National Collection at the Lee Kong Chian Reference Library within the new building. Additionally, the stories and memories of users and patrons of the former National Library have been recorded in publications and in oral history interviews with the National Archives of Singapore. These efforts will ensure that the legacy of the red-brick building will not be lost to future generations.13

Lim Tin Seng is a Senior Librarian with the National Library Singapore. He is the co-editor of Roots: Tracing Family Histories – A Resource Guide (2013), Harmony and Development: ASEAN-China Relations (2009) and China’s New Social Policy: Initiatives for a Harmonious Society (2010). He writes regularly for BiblioAsia.

Lim Tin Seng is a Senior Librarian with the National Library Singapore. He is the co-editor of Roots: Tracing Family Histories – A Resource Guide (2013), Harmony and Development: ASEAN-China Relations (2009) and China’s New Social Policy: Initiatives for a Harmonious Society (2010). He writes regularly for BiblioAsia.NOTES

-

“Cultural Awakening at Opening of New National Library,” Straits Times, 13 November 1960, 5; Lydia Aroozoo, “S’pore’s New Landmark,” Singapore Free Press, 12 November 1960, 7. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

K.K. Seet, A Place for the People (Singapore: Times Books International, 1983), 115. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 027.55957 SEE) ↩

-

“Start Made on Free Library,” Straits Times, 17 August 1957, 4; “$2½ Mil. Library Is Free,” Singapore Free Press, 16 August 1957, 2; “City’s New $2 Mil Library,” Sunday Standard, 20 November 1955, 3. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Library Building in Singapore Is Severely Criticised,” Straits Times, 4 July 1960, 7; Ian Mok-Ai, “They Gasp with Horror at This ‘Monstrous Monument’,” Singapore Free Press, 9 July 1960, 4. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

National Library Board Singapore, Report: 5th December 1960 to 30th September 1963 (Singapore: Government Printing Office, 1963), 4, 9. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RCLOS 027.55957 SIN) ↩

-

National Library Singapore, Annual Report 1964 (Singapore: Government Printing Office, 1967), 1. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RCLOS 027.55957 RLSAR); National Library Singapore, South East Asia Collection (Singapore: Government Printing Office, 1964), 2–6. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RCLOS 027.55957 SIN) ↩

-

S. Rajaratnam, “The Opening of the South East Asia Room and Presentation of the Ya Yin Kwan Collection by Mr. Tan Yeok Seong,” speech, National Library, 28 August 1964, transcript. (From National Archives of Singapore, document no. PressR19640828) ↩

-

National Library Singapore, Annual Report 1964, 1; National Library Singapore, South East Asia Collection, 2–6. ↩

-

Claudette Peralta, “National Library’s $2.6m Facelift,” Straits Times, 12 March 1997, 2. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Jessica Tan, “Library Learns to Put Down the Book and Xpress Itself,” Straits Times, 10 July 1999, 13. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

National Library Board, Annual Report 2004–05 (Singapore: National Library Board, 2006), 37. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RCLOS 027.55957 RLSAR); Theresa Tan, “After April 1, Buy a Chunk of the Old Library,” Straits Times, 29 January 2004, 4; Lydia Lim, “New Plan for Bras Basah Offered,” Straits Times, 25 January 2000, 34; Tan Hsueh Yun, “National Library Building Will Not Be Conserved,” Straits Times, 27 March 1999, 51; Tan Hsueh Yun, “Library Must Go for 2 Key Reasons,” Straits Times, 22 March 1999, 42; “A Cultural Asset That Inspires All,” Straits Times, 12 November 2005, 20. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Adeline Chia, “A-Z Guide to the New National Library,” Straits Times, 2 July 2005, 2; Tay Suan Chiang, “Green and Bear It,” Straits Times, 23 July 2005, 10. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

National Heritage Board, “Former National Library (Stamford Road) Entrance Pillars,” Roots, last updated 10 September 2021, https://www.roots.gov.sg/places/places-landing/Places/surveyed-sites/Former-National-Library-Stamford-Road-Entrance-Pillars. ↩