The Singapore and Southeast Asia Collection

An invaluable resource for researchers of Singapore and the region.

By Ang Seow Leng

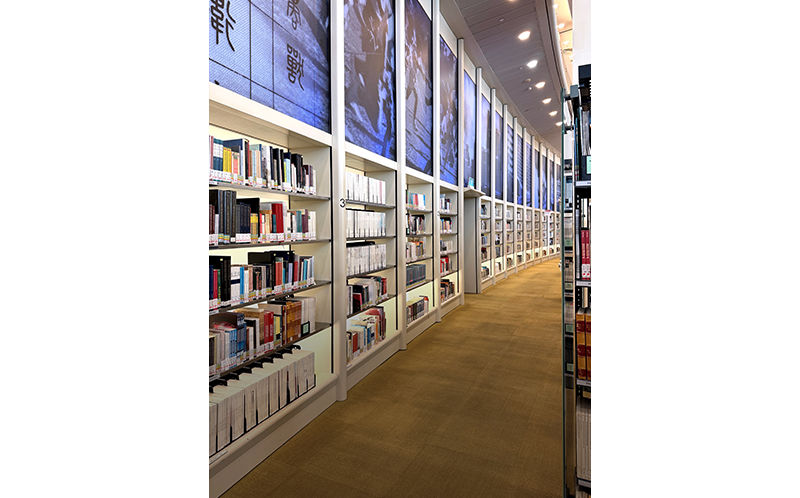

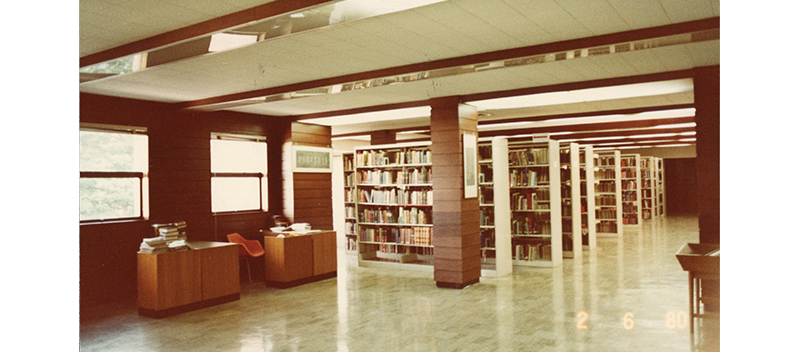

First time visitors to Level 11 of the Lee Kong Chian Reference Library at the National Library Building are typically wowed by the space: from the floor-to-ceiling windows offering a spectacular view of the Singapore skyline to the triple-volume floor with a six-metre-high book wall. But the gorgeous view and the high ceilings pale in comparison to what is on the bookshelves on this floor. Level 11 is the home of the Singapore and Southeast Asia Collection – a valuable source of materials for historical research and discovery into topics relating to Singapore and the region.

The Singapore and Southeast Asia Collection, together with the Rare Materials Collection, the Legal Deposit Collection and the Donors’ Collection, form the National Collection of almost 2 million items at the National Library Singapore.

The Early Years of the Singapore and Southeast Asia Collection

The National Library has its beginnings as the Singapore Institution Library, which was established in 1837 with just 392 elementary education primers.1

In 1845, the Singapore Institution Library was renamed the Singapore Library. By 1874, with a collection of 3,000 volumes, the Singapore Library became a part of the museum. The new entity was called the Raffles Library and Museum, and its objective was to collect “valuable works relating to the Straits Settlements, and surrounding countries, as well as standard works on Botany, Zoology, Mineralogy, Geography, and the Arts and Sciences generally”.2

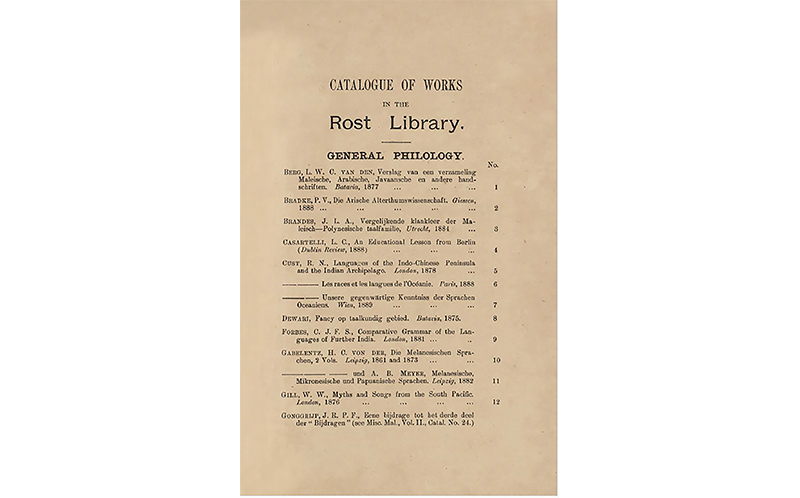

Early acquisitions include the 1879 purchase of the Logan Philological Library belonging to James Richardson Logan, the founder and well-known editor of the Journal of the Indian Archipelago and Eastern Asia (popularly known as Logan’s Journal). This consisted of 1,250 works on the ethnography and philology of the Malay Archipelago.3 The Rost Collection was acquired in 1897 from a portion of the private library of Reinhold Rost, the librarian at the India Office Library in London. The 970-volume collection comprises titles relating to the philology, geography and ethnology of the Malay Archipelago.4

The library’s collection grew steadily and by the end of 1900, there were more than 26,000 volumes.5 The appointment of qualified librarian James Johnston in 1920 to manage the Raffles Library was a landmark in the library’s history. He was instrumental in organising works on Malaya and the surrounding islands into a special Malaysia Collection in 1924. The library’s collection continued to grow and gain traction from there.6 In 1923, the library of the Malayan Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society was transferred “on permanent loan” to the Raffles Library as the society’s council felt that it would “receive more attention and care in the larger library”.7

The move back to the Raffles Institution building in 1876 presented an opportunity to reclassify the growing collection. The simple six-genre arrangement was expanded into 24 subjects, each represented by a letter of the English alphabet. The letter “Q”, for instance, was given to “Works on Singapore, the Straits Settlements and the Eastern Archipelago”.8

Fortunately, the Japanese Occupation (1942–45) did not do much damage to the collections of the museum and library. After the war, the library focused on rebuilding its collection which increased to 70,000 volumes by 1947. This figure reached 80,000 volumes by 1955.9

In 1955, the Raffles Library and Museum was separated into two entities and plans were also made for the library to have its own separate building next door.10 Raffles Library was renamed Raffles National Library in 1958 after the Raffles National Library Ordinance took effect. It moved into its new premises in November 1960 and a month later, the Raffles National Library became officially known as the National Library.11

Opening of the South East Asia Room

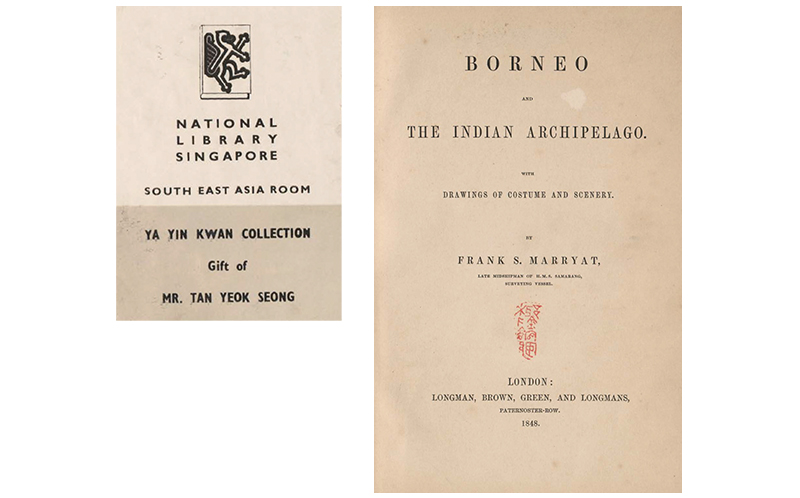

One of the more important additions to the library’s collection in the early postwar years is the Ya Yin Kwan (Palm Shade Pavilion) Collection, donated by Tan Yeok Seong (1903–84), the founder of Nanyang Book Company. A historian and collector of books and historical artefacts, Tan devoted his life and time researching Southeast Asian history, especially the influence of the Chinese in Southeast Asia.

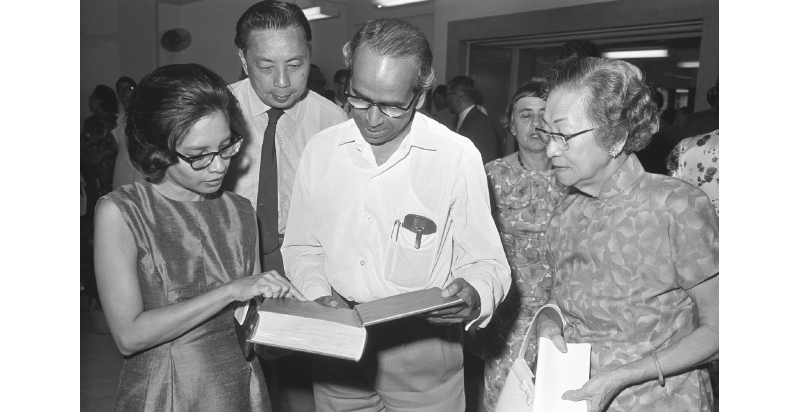

In 1964, Tan donated his collection to the National Library with the condition that a South East Asia Room (SEA Room) be set up to house the collection and make it accessible to the public. His wish was for the donation to be a catalyst for more donations and for the National Library to become a centre for Southeast Asian studies.12 Since the majority of the publications about this region in the early 19th and 20th centuries were mainly by Europeans, Tan hoped for more Southeast Asian scholars to write their own history.

The SEA Room was officially opened on 28 August 1964, with Culture Minister S. Rajaratnam as the guest of honour. “Today’s occasion is one that makes Singaporeans and Malaysians proud,” said Rajaratnam. “From the closed stacks at the back of the building our librarians have now brought out this famous collection.”13

In June 1965, the Singapore and Southeast Asia Collection was further enriched by Mrs Loke Yew’s donation of books and journals originally from the personal library of the late Carl Alexander Gibson-Hill (curator at the Raffles Museum and editor of the Journal of the Malayan Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society). Mrs Loke Yew was the mother of Loke Wan Tho, the chairman of the board of the National Library from 1960 until his death in 1964.14

“I welcome this opportunity of fulfilling my son’s intention, thereby not only perpetuating the memory and names of these two close friends (Dato Loke and the late Dr Gibson-Hill) but also providing a source of knowledge for many young men in the years that lie ahead,” said Mrs Loke Yew at the presentation ceremony.

The SEA room gave prominence and importance to works on Southeast Asia, including titles relating to Singapore. The Gibson-Hill, Logan and Rost collections were housed in the SEA Room, along with materials on Malaysia, Burma (now Myanmar), Thailand, Vietnam, Laos, Cambodia, Brunei, Indonesia and the Philippines.15

In the ensuing decades, the National Library continued to add rare and important Singapore and Southeast Asian materials, either through purchase or from donations. The current strengths of the National Library’s collections and services on Southeast Asia owe much to the farsighted policies during this period of the 1960s.

In 1997, the National Library on Stamford Road underwent an extensive six-month makeover. When it reopened in October that year, the SEA Room had been converted into the Singapore Resource Centre, which was publicly accessible.

Part of the collection from the SEA Room was recategorised as the Singapore Collection and placed in the Singapore Resource Centre, while the rare and valuable materials were moved into a new space called the Heritage Room that was not accessible to the public. (The Heritage Room’s collection is now the Rare Materials Collection at the National Library Building on Victoria Street.)16

Growing the Singapore and Southeast Asia Collection

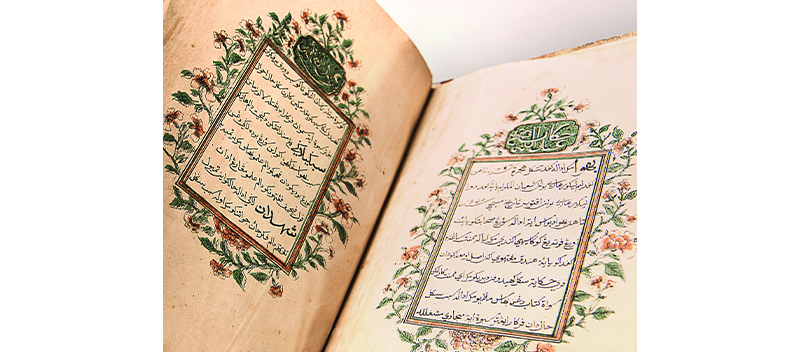

The early acquisitions, donations and titles from the Singapore Library form part of the Rare Materials Collection today. The collection covers language and literature, religion, history and geography, focusing on Singapore and Southeast Asia from the 15th to the early 20th centuries. Many of the titles were produced by Singapore’s earliest printing presses such as the Mission Press of the London Missionary Society.

Donations and gifts, including items that were not available for purchase, add diversity and depth to the National Library’s collections. Over the years, the National Library is fortunate to have been the beneficiary of the personal collections of collectors, researchers and scholars, who systematically accumulated important reference materials over their years of study, or from individuals or institutions that hold heritage materials of value such as manuscripts, private papers, letters and photographs. These items contribute to the preservation of Singapore’s documentary heritage.

The National Library safeguards the published heritage of Singapore. Works published in Singapore are deposited with the National Library and these also make up part of the Singapore and Southeast Asia Collection. Known as legal deposit, it is the legislation by which a country ensures that copies of every publication produced and printed in the country are deposited with one or more designated repositories – usually a library.

Legal deposit is enshrined in the National Library Board Act (Chapter 197), which sets out the functions and powers of the National Library Board (NLB) to acquire, organise, preserve and make accessible Singapore’s published legacy. Under the act, all library materials published and distributed in Singapore have to be deposited with the National Library. This includes two copies of every published material in a physical format and one copy in an electronic format. From 2018 onwards, the National Library also began archiving websites containing the .sg domain without needing to seek written permission from content owners.17

In 2014, NLB became a member of the Biodiversity Heritage Library consortium, the world’s largest open-access digital library for biodiversity literature and archives. Along with other local institutions such as the Singapore Botanic Gardens and the National Parks Board, Singapore offers digital documentations with information on the flora and fauna in Southeast Asia from the 19th century to the present, depicting the rich biodiversity of the region.18

Since 2016, the National Library has embarked on the Singapore Digital Resource Project that aims to enrich the Singapore and Southeast Asia Collection and fill gaps. There have been several collaborations with overseas institutions to digitise, acquire digitised copies and make accessible the archival and printed materials of Singapore and Southeast Asia held by them. For instance, a five-year project with the British Library, which began in 2013, saw the digitisation of Malay manuscripts, early maps of Singapore and papers relating to Stamford Raffles, thanks to a kind donation of £125,000 from William and Judith Bollinger.19

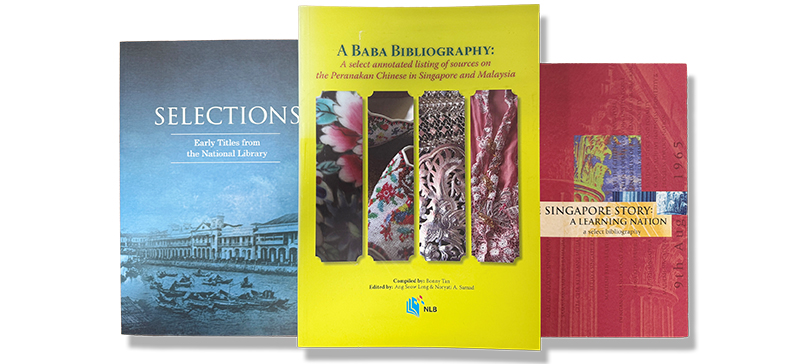

The strengths of the Singapore and Southeast Asia Collection are titles on the history (particularly Malayan colonial history), government, language and literature, and sociocultural descriptions of Singapore, Malaysia and the region. The materials are primarily in the four official languages – English, Malay, Chinese and Tamil. However, there are also items in European languages (for instance French and German), Japanese and some Southeast Asian languages (such as Indonesian, Thai and Tagalog).

Although print publications make up the core of the collection, there are also resources in formats such as microforms, maps, photographs, posters, ephemera, audiovisual and electronic databases. Together, they present a sense of the history, time and place of the people, societies and cultures of Singapore and the region, the changes in collection and research focus, as well as hot-button issues and how these have evolved over the years.

As the National Library continues to be a repository of the nation’s documentary heritage and builds the collection through acquisition, donations, gifts and exchange with other libraries and digital acquisition, it also aims to be a leading resource centre on Southeast Asia.

Users of the Singapore and Southeast Asia Collection

Many researchers and scholars have benefitted from the Singapore and Southeast Asia Collection through the years. The late Professor Ian Proudfoot (1946–2011) was an Australian researcher and former SEA Room user. He studied the Malay manuscripts collection held at the National Library during his early career and became one of the greatest philologist scholars on early Malay printing. He also found love in the SEA Room and got married to one of the librarians.

The library regularly receives visits from former residents of Singapore or their descendants who are tracing the history of their forebears. They would scan newspaper articles or ask for street directories to check whether there have been changes to the street names or places where they used to live.

There have also been requests and visits by overseas institutions to use our resources for their research needs. For instance, in 2019, staff from the Xiamen Tan Kah Kee Memorial Museum requested to view all related resources available at the library on the businessman and philanthropist Tan Kah Kee in preparation for their anniversary celebrations.

The annual Lee Kong Chian Research Fellowship also sees batches of local and overseas researchers diving deep into the collection for their research topics. For instance, Anh Sy Huy Le, an Assistant Professor of History at St Norbert College, De Pere, Wisconsin, was awarded the Fellowship in January 2020. His research topic, “Trade, Colonialism and Diaspora: Chinese Rice Commerce and the Transformation of Sài Gòn–Chợ Lớn in Colonial Vietnam”, examines the confluence of Chinese migration and diasporic capitalism in transforming Sài Gòn–Chợ Lớn in the 1870s into a central trade emporium and prominent colonial port city.20

More recently, in 2022–23, Sharad Pandian, who graduated from the Nanyang Technological University with a degree in physics and holds a Master of Philosophy in History and Philosophy of Science at the University of Cambridge, discusses the standardisation and the promulgation of quality-consciousness by the Singapore Institute of Standards and Industrial Research (SISIR) in his topic, “‘Prosperity Through Quality and Reliability’: SISIR and the Making of a Quality Conscious Nation”.21

Library patrons have increasingly relied on digitised resources that the librarians put up online. The National Library Collections Directory provides an overview of the library’s rich Singapore content through a wide range of resources, including donor materials across different subjects and formats.

As research methods evolve over time with resources available beyond print, the strong link between collections, librarians and library users will remain constant.

Ang Seow Leng is a Senior Librarian with the National Library Singapore. Her responsibilities include managing the Singapore and Southeast Asia Collection, developing content as well as providing reference and research services relating to Singapore and Southeast Asia.

Ang Seow Leng is a Senior Librarian with the National Library Singapore. Her responsibilities include managing the Singapore and Southeast Asia Collection, developing content as well as providing reference and research services relating to Singapore and Southeast Asia.Notes

-

Singapore Institution Free School, Fourth Annual Report 1837–38 (Singapore: Singapore Free Press Office, 1838), 59. (From National Library Online) ↩

-

Walter Makepeace, Gilbert E. Brooke and Roland St. J. Braddell, eds., One Hundred Years of Singapore, vol. 1 (Singapore: Oxford University Press, 1991), 546. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 959.57 ONE) ↩

-

“Untitled,” Straits Times Overland Journal, 20 December 1879, 7; “The Council’s Annual Report for 1879,” Straits Times Overland Journal, 11 February 1880, 3. (From NewspaperSG); Raffles Museum and Library, Annual Report for the Year 1879 (Singapore: The Museum, 1880), 1. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RRARE 027.55957 RAF; microfilm no. NL3874) ↩

-

Makepeace, Brooke and Braddell, One Hundred Years of Singapore, 559. ↩

-

Raffles Museum and Library, Catalogue of the Raffles Library, Singapore, 1900 (Singapore: American Mission Press, 1905), 1. (From National Library Online) ↩

-

Lim Huck Tee, Libraries in West Malaysia and Singapore, A Short History (Kuala Lumpur: University of Malaya Library, 1970), 74–75, 82. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 027.0595 LIM-[LIB]) ↩

-

“Royal Asiatic Society,” Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser (Weekly), 27 February 1924, 134. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Gracie Lee, “Collecting the Scattered Remains: The Raffles Library and Museum,” BiblioAsia 12, no. 2 (April–June 2016), 39–45. ↩

-

“Raffles Museum Treasures Safe,” Malaya Tribune, 23 October 1945, 2–3; “Donor Gives 60 Books to Raffles Library,” Sunday Tribune, 9 November 1947, 3; “Asiatic Readers at Library Have Doubled,” Straits Times, 8 December 1946, 7; “More Asiatic Than European Readers,” Singapore Free Press, 24 April 1947, 2. (From NewspaperSG); National Library Singapore, Annual Report 1963 (Singapore: Government Printing Office, 1964), 2. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RCLOS 027.55957 RLSAR-[AR]) ↩

-

“Start Made on Free Library,” Straits Times, 17 August 1957, 4; “$2½ Mil. Library Is Free,” Singapore Free Press, 16 August 1957, 2; “City’s New $2 Mil Library,” Sunday Standard, 20 November 1955, 3. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Hedwig Anuar, “Singapore’s National Library,” Straits Times Annual, 1 January 1962, 58–59; “Out Goes the Name Raffles,” Straits Times, 21 November 1960, 9; “Raffles’ Name Will Live On: Rajaratnam,” Straits Times, 1 December 1960, 7. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Ang Seow Leng and Jane Wee, comps., Catalogue of the Ya Yin Kwan Collection in the Lee Kong Chian Reference Library = 椰阴馆藏书目录 = Ye yin guan cang shu mu lu, ed. Lai Yee Pong, Lynn Fong and Noryati Abdul Samad (Singapore: National Library Board, 2006), 16. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING q338.092 TAN) ↩

-

S. Rajaratnam, “The Opening of the South East Asia Room and Presentation of the Ya Kin Kwan Collection by Mr Tan Yeok Seong,” speech, National Library, 28 August 1964, transcript. (From National Archives of Singapore, document no. PressR19640828) ↩

-

“Books Gift By Mrs Loke Yew Fulfils Wish of her Late Son,” Straits Times, 11 June 1965, 6; “Gift of Rare Books to Library,” Straits Times, 19 June 1965, 4. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“SE-Asia Room of Library Opens Today,” Straits Times, 28 August 1964, 5. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

K.K. Seet, Knowledge, Imagination, Possibility: Singapore’s Transformative Library (Singapore: SNP International Publishing Pte Ltd, 2005), 33, 97. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING q027.5597 SEE-[LIB]); “Have a Cuppa with Your Book at the Library,” Straits Times, 17 January 1998, 57. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Republic of Singapore, National Library Board (Amendment) Act 2018, No. 30 of 2018, Government Gazette Acts Supplement, Singapore Statutes Online, last updated 1 April 2025, https://sso.agc.gov.sg/Acts-Supp/30-2018/Published/20180813?DocDate=20180813. ↩

-

“About the Biodiversity Heritage Library,” Smithsonian Libraries and Archives, accessed 27 March 2025, https://about.biodiversitylibrary.org/; Lim Tin Seng, “A Slice of Singapore in the Biodiversity Heritage Library,” BiblioAsia 15, no. 3 (October–December 2019): 58–61. ↩

-

“Rare Historical Materials Made Accessible Through Partnership Between British Library and National Library Board of Singapore,” National Library Board, 19 August 2013, https://www.nlb.gov.sg/main/about-us/press-room-and-publications/media-releases/2013/rare-histo-materials-made-accessible-through-partnership-between-british-library-and-nlb-of-singa. ↩

-

Anh Sy Huy Le, “Trade, Colonialism and Diaspora: Chinese Rice Commerce and the Transformation of Sài Gòn–Chợ Lớn in Colonial Vietnam,” in Chapters on Asia 2020 (Singapore: National Library Board, 2021), 7–37. (From National Library Online) ↩

-

Sharad Pandian, “‘Prosperity Through Quality and Reliability’: SISIR and the Making of a Quality Conscious Nation,” Chapters on Asia, 2024, https://biblioasia.nlb.gov.sg/chapters-on-asia-2024/sisir-standards-quality-control/. ↩