A Survey of the Development of the Singapore Chinese Catholic Mission in the 19th Century

For the Singapore Catholic Church, mission growth has hinged on the progress and participation of the Chinese Catholic community, and this became the mission strategy for the establishment of a localised Catholic Church in Singapore.

The Genesis

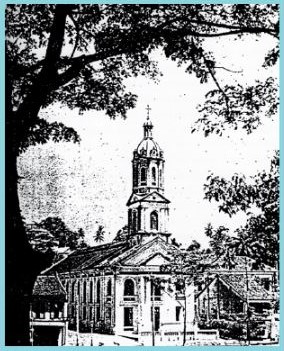

Although the first Catholic clerics and their followers on the island were members of the Portuguese mission coming out of Malacca in the1820s, they did not found a mission for the thousands of immigrants who had landed here. They had a “parish” but it was not certain that they had erected any church building even after the 1820s.1 It was not until the arrival of the French missionaries of the Societe des Missions Etrangeres de Paris (MEP) in 1832 that the first Catholic chapel and mission for Chinese Christians were established.

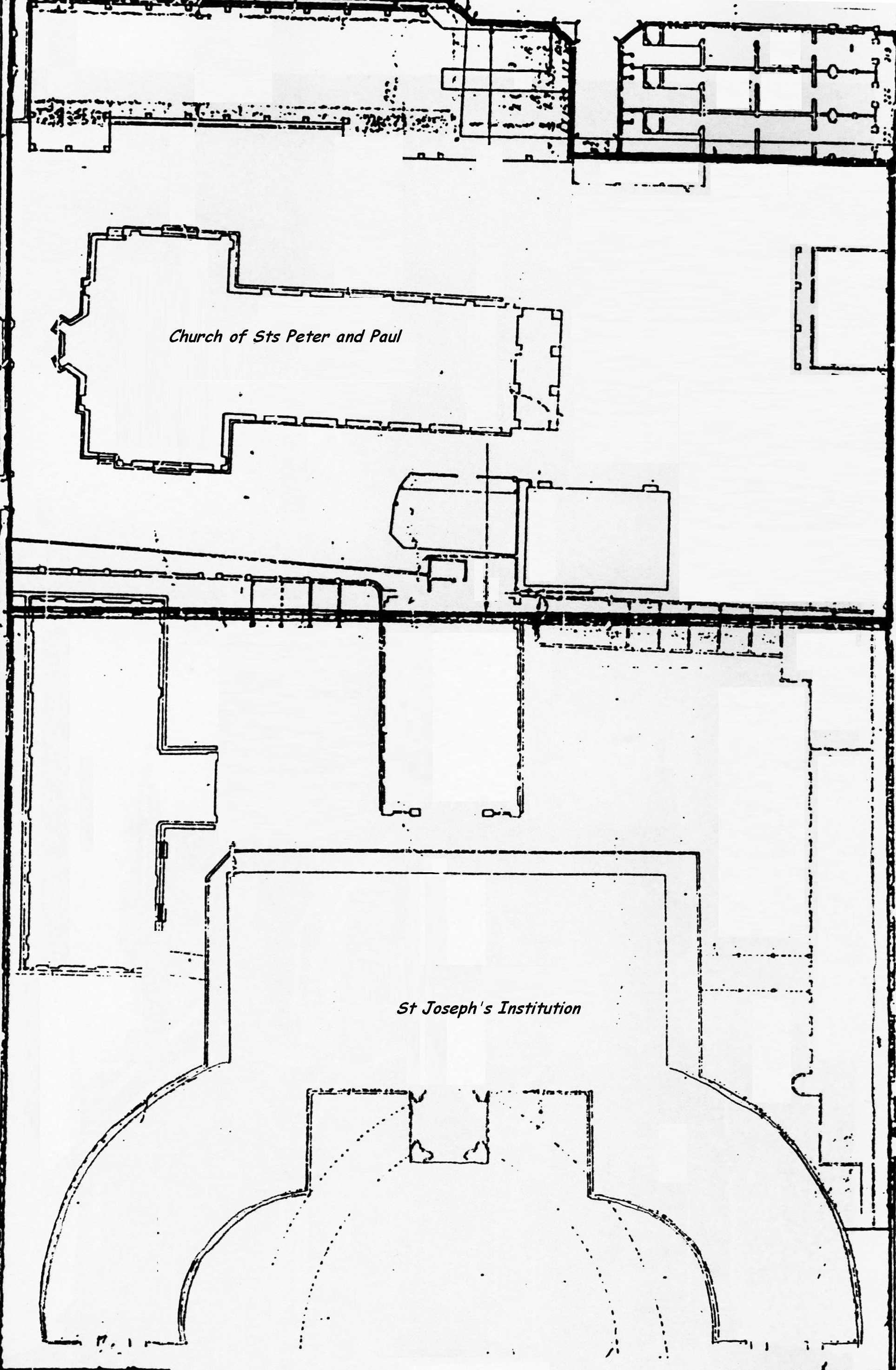

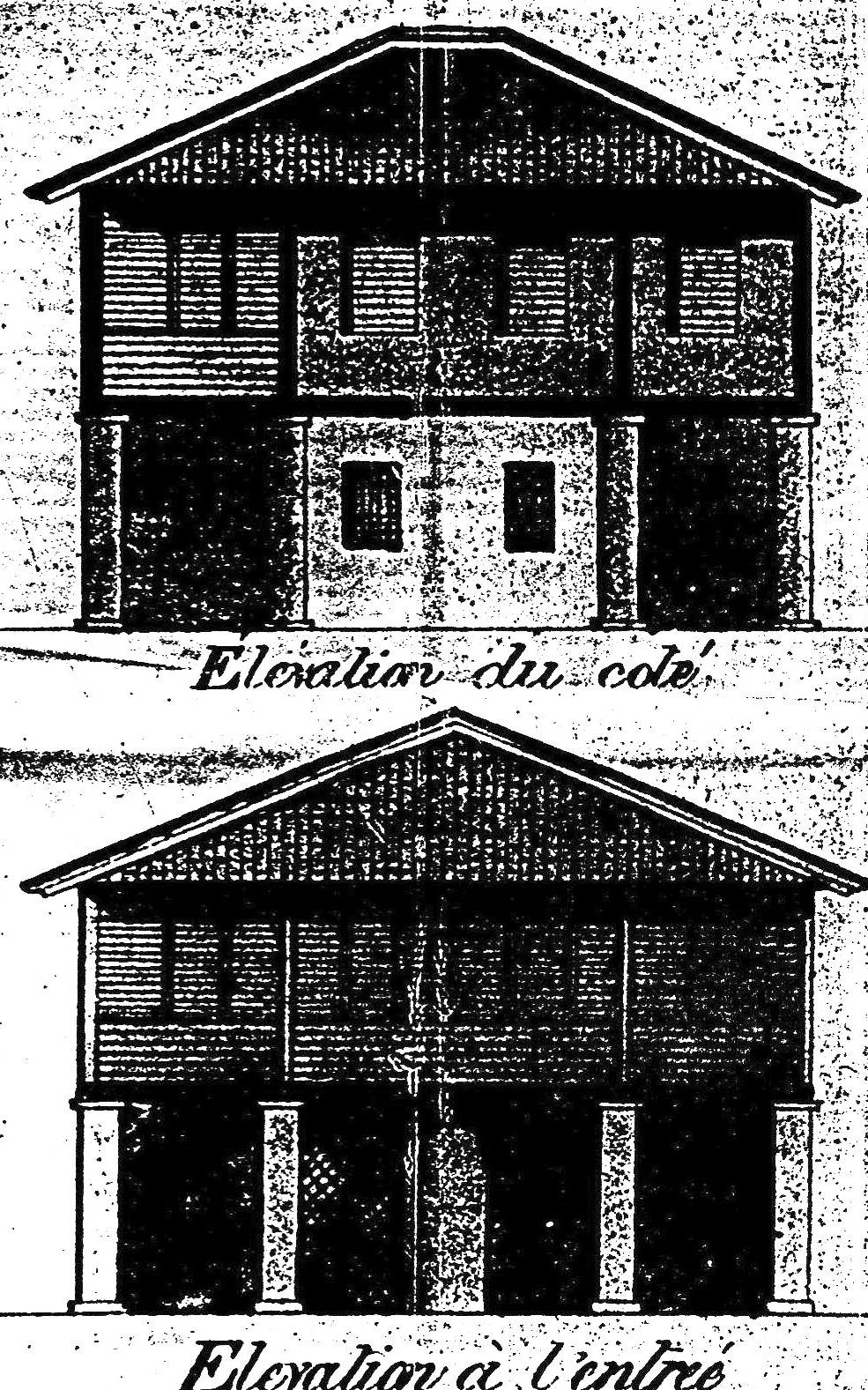

The MEP was able to secure a piece of ground soon after their arrival to establish a French mission station as well as a Chinese Mission upon which they had hoped to build the future Church of Singapore. Both institutions were established within the Mission Ground, with the former occupying the front part facing Bras Basah Road and the latter at the back. Today, the entire ground roughly covers the space occupied by a national icon and a National Monument, the Singapore Art Museum and the Church of Sts Peter and Paul, respectively. The MEP completed their chapel in 1833, a simple 60 by 30 feet plank fourwalled structure,2 which they blessed and named the Church of the Good Shepherd.3 It was only a year later that a Mission House (and catechumenate) for Asian Catholics was completed at the back of the Mission Ground,4 and this was to become the seed of the future Chinese Catholic missions in Singapore.

The First Chinese Christians and The French Mission

Many of the early immigrants who came seeking their fortunes originated from Siam, Penang, Malacca and the Riau Islands. They were closely followed by their brethrens from China, particularly from Chao Chou in Kwangtung. Many of them were Teochew and Hakka speaking migrants who laboured in the jungles of Singapore as well as in the dockyards along the coasts. It is among these migrants that the first resident MEP priest, Fr Etienne Albrand, assisted by a Chinese catechist from China, had found his first Chinese converts. His catechist had also come to Southeast Asia in search of a fortune. Having found the faith in Penang, he ventured from Borneo to Batavia and back to China to spread the “Good News”, before returning to these parts to serve with Fr Albrand.5

Both Fr Albrand and his catechist spent the day going about town preaching the Christian faith to the people along the streets, and some eventually turned up at the Mission Ground for instruction.6 Every evening, from 8pm to 10pm, the Chinese catechist would instruct potential converts, most of them Teochews, in Fr Albrand’s house.7 The French missionary at that time had yet to learn any of the Chinese dialects so he worked mainly among the Malays while this catechist taught the Chinese. Sometimes, to reward his new “students”, Fr Albrand would offer them tobacco and tea.8 By September 1833, he had already a hundred Chinese converts (and Fr Albrand only arrived in May that year).

The Mission’s modest success was however, not without difficulties. The converts as well as the ones preaching conversion were constantly in “danger”. The French missionary and his catechist were shadowed by members of the local Chinese secret society on a daily basis. They had hoped to deter their fellow Chinese from listening to these evangelists. They called Fr Albrand, “the Head of the Devil”, and they threatened to cut the pigtails and tear the clothes off whoever dared to convert.9 Protestant missionaries had also attempted to obstruct the work of the French Mission by “visiting” the class taught by the Chinese catechists.10

It is probable that without the aid of his Chinese catechist, Fr Albrand might not have succeeded in founding his Chinese Mission. The MEP had trained generations of Chinese catechists to assist their missionaries in Asia. The case of the Singapore MEP venture underscores the wisdom of this mission strategy.11 The MEP had maintained a seminary, College General, outside of China since the 17th century.12 Originally established in Ayuthia, this seminary was relocated all over Siam till it found a permanent site at Penang in the first decade of the 19th century. Fr Albrand’s catechist, who was also a Chinese physician, had received his training here. It was also this catechist who taught Fr Albrand Teochew, the dialect of many of his converts. In 1834, with the assistance of this catechist, Fr Albrand was also able to convert 30 Chinese in the Riau islands.13

The MEP found it easier to convert the Chinese when they were overseas than in China. The missionaries had reported that in the Nanyang, detached from their traditional socio-political network, the Chinese had less fear of reprisal from the Chinese authorities or the objection from within their own home communities.14 However, it was not simply because conditions overseas were more ideal, it was also partly because the Missions remained socially relevant to the overseas Chinese. Fr Albrand wrote in 1833 that he had to constantly help his catechumens who faced injustices. He would go to their aid and “protect them like the government”.15 And when conversion meant that they would be rejected by their own Chinese community, the Church offered an alternative community from which they could seek aid and security, just as the missions in China had done.16 In Singapore, the Chinese Catholic community had evolved outside the framework of the immigrant Chinese social order, where the Chinese secret societies had become the de facto government. In this scheme of things, the Chinese Mission, it seemed, had functioned as an imperium in imperio, while it was at the same time, part of a larger Chinese community that transcended political boundaries.

The Expansion Of The Chinese Mission in Town and Beyond

In 1839, the Chinese Mission received its first Chinese priest from China, Fr John Tchu. Like Fr Albrand’s catechist, Fr John Tchu was also a respectable Mandarin. Fr Tchu was sent by a French missionary in his youth to the College General in Penang for his studies where he was to be trained as a catechist. Having exercised this ministry first in Penang, then in Siam, he was ordained a priest in Bangkok by Mgr. Courvezy in 1838 a physician.17 Born in Canton of a Mandarin, and posted to Singapore in the following year where he served as a priest to the Chinese Mission till he died on 13 July 1848. It was acknowledged, after Fr Tchu’s death in 1848, that his work with the Chinese Christians had had a great impact on the Chinese Mission in Singapore.18 From 1840 to 1848, with the conversion of a great number of Chinese, the Church doubled in size.19

The Mission had grown so large in the 1840s that it became necessary to build a larger place of worship for the Catholics of Singapore. This new Church of the Good Shepherd was completed in 1846–47 across the road from the old Mission ground. All Catholics of the French Mission from thence worshipped there, though the Chinese Christians continued their activities on the old Mission ground. The old chapel was then turned into a school for the Mission. In that same year, the Chinese Christians raised the funds to erect their own house of instruction on the old grounds.20

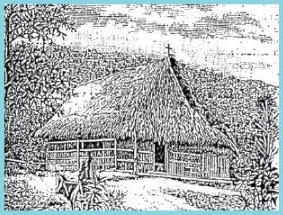

While the Chinese Mission in town grew in number, the French Mission commenced their mission in the jungles of Singapore in 1846. They started a mission outpost at Kranji for the many Teochew Catholic converts who had gone into the interior to grow gambier and pepper. This chapel was dedicated to St Joseph. In 1852, they shifted this station to Bukit Timah where it still stands today. A year later, another Chinese station was started at Serangoon for the Chinese Catholics of Kranji and town who had migrated there in the 1840s.21 The French Missionaries christened this outpost, the St Mary’s Church, and it was later renamed the Church of the Nativity of the Blessed Virgin Mary.

These Chinese outstations were placed under the jurisdiction of the head of the Chinese Mission. The Catholics of these outstations themselves kept their close links with the Church. In fact, many of these Christians had turned to Fr John Tchu to arbitrate in their affairs. On major feast days, the Catholics of the outstations would also join their brethrens for celebrations, often ending with a Chinese dinner on the Mission grounds.22 The close link between the town and jungle missions cannot be more underscored than during moments of crisis. In 1849, when the secret society ran amok in the interior of the island, attacking Catholics, the converts of the outstations, numbering in hundreds, took refuge with their Chinese brethren.23 In 1851, when a bigger and bloodier attack took place, it was speculated that 500 Chinese converts were massacred across the island.24 Once again, the survivors had to seek refuge with their brethren in Town where the Chinese Mission had a house for the sick next to their catechumenate.

The Chinese Mission in the jungle ultimately survived and continued to grow, albeit at a slower pace in the following decades. In early February 1853, the MEP erected a small chapel at the end of Serangoon Road that cost $800.25 This mission station was, however, too small at this time to require a permanent missionary to be stationed there. Hence, the MEP missionary to the outpost’s missionary was stationed in town from where he visited the Serangoon Catholics.26 By 1859, although there were in all only 140 Chinese Catholics at this station,27 it was constituted by an increasing number of Chinese Catholic families. Fr Beurel, the head of the Singapore Mission then, had made a request to the government in 1857 for a grant to a piece of land near the Serangoon chapel where he could settle these newly arrived Catholic families who could grow vegetables there.28 Although only 34 acres of the 114 acres of land requested was granted in 1858,29 it was more than sufficient to plant a new Christian enclave at the far end of the island.

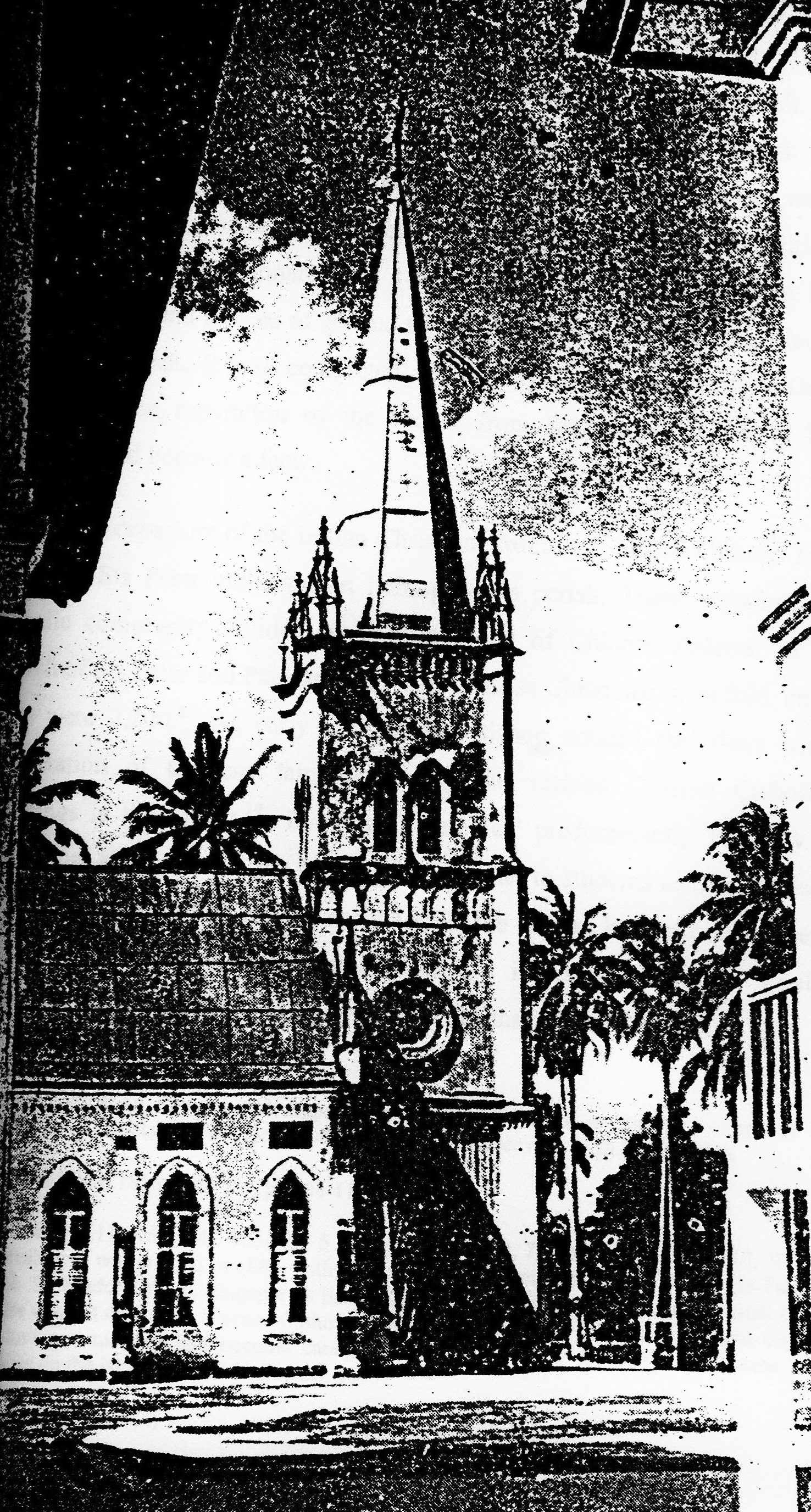

The First Chinese Catholic Church

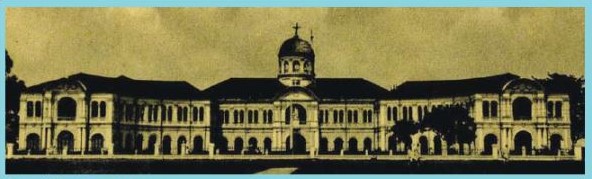

When the Christian Brothers of St John Baptist de la Salle arrived to found a Christian school for the boys of Singapore in 1852, the old chapel was given to the Brothers who then established St Joseph’s Institution. Next to this new school (the old chapel), the Chinese Mission maintained a Chinese school for boys which had a branch for the Indians. The boys of the Chinese school were instructed by a teacher from China. At this point, the Chinese Mission shared the front part of the old Mission Ground with the Brothers. However, by the early 1860s, when the enrolment at the Brothers’ school had grown so large that a new school building was needed, it became necessary for “spaces” to be more defined. At this time, the Chinese Catholic community had also grown enormously. It was then decided to divide the Mission grounds permanently with St Joseph’s Institution (the Brothers’ School) occupying the portion fronting Bras Basah Road. The Chinese school was then transferred to Kranji.30 This separation in effect paved the way for the Chinese Christian community to finally erect a place of worship of their own, the Church of Sts Peter and Paul.

The missionary given the colossal task of building the Church of Sts Peter and Paul was Fr Pierre Paris. Fundraising was difficult as most of the Chinese Christians were poor. But fortunately, amongst them was a wealthy and influential Chinese Christian, Pedro Tan No Keah,31 who managed to raise the necessary funds. The church was completed in 1870 on the site of the original Chinese Mission. It was from Sts Peter and Paul that Fr Pierre Paris continued to plant the seeds of the future Chinese Catholic (and Tamil) churches of Singapore. Every Sunday morning, he walked the length of Serangoon Road to say mass for his flock there (Nativity Church) before returning to Sts Peter and Paul to hold service for the Tamils at 11am. After that, he held mass at the jail before returning to his parish at 2pm in the afternoon to conduct catechism for the Chinese children. Then, at 3pm, he had Vespers in the parish. On Mondays and Wednesdays, he dealt with the temporal affairs of his Chinese in town. On Tuesdays, he visited the Chinese in the jungles. On Thursdays, he taught the catechumens at Serangoon who used to travel long distances to him. The last two days of the week were given to confession and other works.32

Fr Paris was also the first missionary in the Mission who spoke Tamil, a language which he picked up from Malacca. Thus, with him, the seed for an Indian Mission was also planted. For them, he started a school, the St Francis Malabar School, which was located along Waterloo Street.

By the time of his death, there was already a small Indian congregation in the making. They too worshipped in the Church of Sts Peter and Paul together with the Chinese.

Planting Other Chinese Catholic Communities

While the European and Eurasian Catholics of the settlement had remained “pastoral” and based mainly within the town churches of St Joseph’s (Portuguese Mission) and Church of the Good Shepherd (MEP), church growth was characterised by the growth of the Chinese Mission communities. Towards the mid-1850s, the planted Chinese Catholic communities of Singapore had already begun to impact the establishment of other Chinese Catholic communities in the region in a profound manner. The first instance of the Mission’s extension into Peninsular Malaya was in 1853, when Chinese Catholic families from the island were transplanted to Malacca to form the nucleus of an agricultural community that was calculated to attract the Chinese there to convert.33 In the 1860s, as the Mission at Bukit Timah was making inroads north of the island to Boo Koo Kangkar (Kranji), Catholic families from Serangoon had begun re-migrating to Johore where they found new economic opportunities planting gambier and pepper. By February 1861, the MEP decided that they should establish a Mission station for these Chinese Catholic re-migrants.34 In July 1861, the Mission secured a grant from the Temenggong of Johore for a piece of land to start their station, and this led Fr Paris to begin his visits to the Chinese Christians there. However, nothing resulted from this evangelical endeavor.35

The more significant mission foray into Johore was actually achieved by Fr Augustine Perie from his stations at Bukit Timah and Boo Koo Kangkar where Chinese Catholics were beginning to migrate to Johore as well. St Mary’s Chapel, a chapel erected by Fr Perie at Kranji, had prospered for a while before an “accidental” fire razed it in early 1863. Fr Perie suspected that the Chinese Secret socities were behind it.36 Coupled with this destruction and the general economic difficulties in the district, many Catholic families had begun to re-migrate to Java and Johore.37 Fr Perie knew that in Johore, without a missionary, his Chinese converts would eventually give up Christianity. Hence, he made preparations to found an agricultural colony in Johore for the Christians.

Fr Perie’s goal was to transplant a portion of his Catholic community from Bukit Timah and Boo Koo Kangkar to this new agricultural colony to establish another Catholic enclave up north. A piece of land at Pontian Kitsil, on the western side of Johore, was granted by the Maharajah of Johore in mid-1863. Fr Perie then set out with a few of his Chinese Christians on 18 August 1863 to survey the jungle plains of Pontian Kitsil for land clearance.38 In all, 32 Chinese Christians set up plantations on both sides of the Pontian River, which ran down the middle of Pontian Kitsil. At the heart of this plain, Fr Perie established his Mission station with a vegetable garden, school and a house-chapel that he dedicated to St Francis Xavier.39 In the agreement with the Maharajah, the land was granted to Fr Perie on the condition that he assumed the position of the kangchu, the headman or master of the river. A regular kangchu was responsible for the law and order of his district as well as the monopoly rights over trading, spirits, gambling and supply of opium. Fr Perie, however, forbade gambling and opium in his colony, and this turned many potential non-Christian Chinese settlers away.40

There were high hopes for this colony but the marshy terrain had made life extremely difficult, and that further deterred other potential settlers. In 1864, a great fear arose among the Christians of Singapore and Johore that the secret society was about to launch an all out attack against the Church. The fear of an impending attack, and the spectre of another “Bloody 1851”, eventually led most of the Singapore Christian migrants to Pontian to abandon their plantations, leaving only 15 Chinese planters.41 Discouraged, Fr Perie moved further inland in 1865 to work among the indigenous aborigines there. The Pontian station however, continued with missionaries from Bukit Timah visiting it intermittently. The register for St Francis Xavier’s Chapel, from 1864 to 1873, is still kept in the archives of St Joseph’s Church, Bukit Timah. On record, from those years, there were 22 infant baptisms, 85 adult conversions, 11 marriages and 30 burials.42

By the 1870s, numerous Chinese Catholic enclaves had already been established in the northern part of the island and beyond. Located far apart and in very different environs, they remained similarly constituted. The Chinese Missions at Bukit Timah, Serangoon and in town had their own attached schools, hospitals (infirmaries) and cemeteries,43 making them self-contained communities within their own districts. Given the historical ties with the Singapore Church, the Chinese Christians of Pontian and those in other parts of Johore, had always kept their links with their “mother” Church in Singapore by making annual pilgrimages to St Joseph’s, Bukit Timah, on all major feast days.44

In 1881, the main mission initiative to Johore shifted from Bukit Timah to the Serangoon Mission, following Fr Laurent Saleilles’ reassignment there. When Fr Laurent Saleilles arrived in 1877, he was first posted to Bukit Timah from where he visited Pontian several times a year.45 In time, he included on his itinerary other parts of Johore where he initially found 36 Chinese Christians who had migrated from Singapore, scattered all over. From January 1881, after Fr Saleilles was posted to Serangoon, he concentrated his efforts at Johore Bahru. Pontian then, had become too far from where he was stationed. Fr Saleilles had initially gathered his first converts at his rented residence at Johore Bahru, and by early 1882, he had already converted 63 Chinese.46 An application to the Maharajah for a piece of land to erect a church in Johore Bahru was made in September 1881. By May 1882, with the assistance of a Catholic British planter in Johore, three acres of land was granted, less than a mile from the town centre.47 The foundation stone for this church, dedicated to Our Lady of Lourdes, was laid on 21 November 1882, and by 29 May 1883, the church was completed, blessed and opened, together with a Chinese catechumenate and a parochial house. Fr Saleilles subsequently established a Chinese school for the children of this Mission at the catechumenate.48 The first Catholic institution in Johore was thus established, an extension of the MEP Chinese Catholic Mission in Singapore and modeled after Singapore’s Chinese Catholic enclaves.

The missionary outreach of Singapore Chinese Catholic community in the 1870s, it appears, had also reached Sarawak as Fr Saleilles had reported making visits there even before being stationed at Serangoon. In July 1880, Fr Saleilles accompanied the American Mill Hill Fathers to Sarawak to help them found their Mission. And even after the establishment of the American Fathers, Fr Saleilles continued his visits the Chinese Catholics there, although jurisdiction over the district had passed on to these new missionaries.49 Perhaps, some Chinese Catholics from Singapore had migrated to Sarawak and Fr Saleilles simply followed them, just as Frs Paris and Perie did when their Catholics ventured into Johore. Following this pattern of Mission development in Malaya, where Catholics always preceded their missionaries, it was probable that the Sarawak and Singapore Chinese Christians were very much linked. It must be noted that as early as the 1840s, Chinese catechists from Singapore had already been reported to have evangelised in Sarawak and Labuan.50

Conclusion

The MEP’s mission strategy in 19th century Singapore, and perhaps generally in Asia, was to plant Catholic communities throughout Asia as a precursor to the establishment of indigenous Churches. The distribution of bibles and mere street preaching, the modus operandi of Protestant missionaries of the day, yielded little in a society that was still transient, mostly illiterate and more concerned with day to day affairs. In the Malay Archipelago, proselytising to indigenous Muslim Malays could only reap certain failure. There were also too few Eurasians and Europeans to form a rooted Church, and besides, they could hardly constitute a localised, or “Asianised” Catholic Church and community. It was left to the sojourning immigrants of East, Southeast and South Asia to provide the critical mass for the creation of a local Christian and Church community.

PhD candidate

National Institute of Education

Nanyang Technological University

NOTES

-

See Straits Settlements Record (SSR), N2 1827, 23 August 1827; Manuel Teixeira, The Portuguese Mission in Malacca and Singapore, vol. 3. (Lisboa: Agencia Geral do Ultramar, 1963), 10. (Call no. RCLOS 266.25953 TEI) ↩

-

J. M. Beurel, Annales de la Mission Catholique De Singapore, Ecrites Par Le Soussigne En Ese Moments De Loisir, 329; Archives de la Missions Etrangeres (AME) 892, 851–54, 23 February 1833. ↩

-

Beurel, Annales, 11–12. ↩

-

AME 892, 1035–7, 8 August 1834; 1051–4, September 1834; Joseph Ruellen, Situation Generale En Asis Du Sud-Est a Liarrivee De Mgr. P. Bigandet, Mai 1834–Nov 1859 (Singapore: MEP House, 1998). Compilation of manuscript correspondences from MEP Archives, Paris, AME, Siam, 27 September 1834, Fr Pallegoix to Mgr Courvezy. ↩

-

Annals de la Propagation de la Foi, Malaisie (APF), vol. XLII, September 1835, pp.124–34, 10 September 1833. ↩

-

Annals de la Propagation de la Foi, Malaisie (APF), vol. XLII, September 1835, pp.124–34, 10 September 1833. ↩

-

Annals de la Propagation de la Foi, Malaisie (APF), vol. XLII, September 1835, pp.124–34, 10 September 1833. ↩

-

Annals de la Propagation de la Foi, Malaisie (APF), 22 November 1834. ↩

-

Annals de la Propagation de la Foi, Malaisie (APF), 10 September 1833 and 26 December 1833. ↩

-

AME 892, 1051–4, Sep 1834; APF, vol. XLII, September 1835, 124–34, 22 November 1834. ↩

-

(APF), vol. XLII, September 1835, 124–34, 10 September 1833. ↩

-

Stephen Neill, A History of Christian Missions (Great Britain: Penguin Books, 1964), 191. As a measure to avoid the persecution of the Manchu Government, College General was located outside China. ↩

-

Ruellen, Situation Generale, AME, Siam, 27 September 1834, Fr Albrand to Mgr Courvezy. ↩

-

APF, September 1835, 124–34, 26 December 1833. Scholars have argued that overseas Chinese, “deprived of their accustomed family and lineage support”, sought out alternative solidarities. Although for the Chinese overseas, “moral constraints of kinship village attachment remained strong”, they were less direct. See Ng Chin Keong, “The Cultural Horizon of South China’s Emigrants in the Nineteenth Century: Change and Perspective”, in Asian Traditions and Modernization. Perspectives From Singapore, ed. Yong Mun Cheong (Singapore: Centre for Advanced Studies, National University of Singapore, 1992), 24–26. (Call no. RSING 959.57 ASI) ↩

-

APF, September 1835, 124–34, 26 December 1833. ↩

-

Jean-Paul Wiest, “Catholic Activities in Kwangtung Province and Chinese Responses, 1848–1885” (PhD dissertation, University of Washington, 1977), 112. ↩

-

AME 893, 975–7, 29 March 1842. Fr Tchu arrived in 1839. ↩

-

Singapore Free Press, 27 July 1848. ↩

-

Beurel, Annales, 68. The number of Catholics had increased from 450, in 1838, to 800, in 1846. From 1839, the Chinese Catholics had already constituted half the Catholics on the island. Of a total of 443 baptisms from 1840 to 1846, 333 were of Chinese converts. See Baptism Register, Cathedral, 1840–1846. It was also during this period that they became more than self-reliant. When the bishop found that it became necessary to erect a wall to enclose the Mission Grounds in 1839, the most influential (European) Catholics of the Mission, having continuously subscribed to the Mission’s building projects in the proceeding years, refused to help. It was Chinese Christians who then came to the bishop’s aid. ↩

-

AME 904/21, 11 May 1845 and 904/32, 7 October 1845. This house was completed by Oct 1845 at a cost of $550. See Beurel, Annales, 126. ↩

-

AME 90, 1401–3, 8 December 1847; 902, 105, 5 May 1848 and 175, 4 July 1848. In 1842, a number of Chinese Christians had started a nutmeg plantation of 17,000 trees with Fr Beurel at Serangoon. It was to raise an annual income of 400 francs from the produce to support the Christian Brothers’ School when it was founded. In December 1849, a seminary was established at the end of Serangoon Road to prepare Chinese candidates for the priesthood, before sending them off to College General in Penang for training. In December 1849, Holy Mary College was established with twelve Chinese seminarians who supported themselves by cultivating nutmeg and coconuts. The college was transferred to Matang Tinggi (near Penang) a year later when eleven of the twelve seminarians withdrew their candidature. See AME 904/94, 18 April 1849; 902, 4 December 1849. ↩

-

SFP, 16 April 1846. ↩

-

SFP, 3 July 1849. ↩

-

See J F McNair, Prisoners Their Own Warders (Westminster: Archibald Constable and Co., 1899), 68 (Call no. RRARE 365.95957 MAC; microfilm NL12115; accession no. B20048144A). Many historians, including CM Turnbull, Carl Trocki and Wilfred Blythe, have quoted this figure. This figure cannot be confirmed by any official sources. If this figure is near accurate, then the Church would have been wiped out! ↩

-

AME 902, 1403–5, 2 February 1853. ↩

-

AME 903, 269–70, 16 December 1854. ↩

-

AME 903, 1515, 17 October 1859. ↩

-

Straits Settlements Record, X16, 1858, 23; W28 1858, 12 October 1858, 58. ↩

-

Beurel, Annales, 490. (This page numbering is from the microfilm copy of Fr Beurel’s journal, MEP Archives, vol. 907. Entries for the years from years 1852 to 1860s are missing in the original copy from which I have been quoting thus far). ↩

-

The school for the Chinese Boys was called St Peter’s School. See Straits Settlements Annual Report, 1865–6, 24/7. ↩

-

Tan No Keah was born at Fuyang City of Zhao’an County, Guangdong Province, in 1821. The family was poor and life was difficult at his hometown, so he borrowed a few pieces of silver and set off to the Nanyang. He first landed in Johore where he worked on a gambier plantation. After having saved some money, he ventured to Singapore where he started gambier plantations at Punggol. Eventually, he was able to build 14 warehouses at Boat Quay. His company was known as “Qianyi” Kongsi, situated at No. 48 Boat Quay (or No. 33 River Valley Road). The company traded mainly in gambier and local produce. He later married a girl from the Convent of the Holy Innocent Jesus (Town Convent) and converted to Catholicism. This information was provided by Tan Keow Meng, great grand-daughter of Tan Tong Seng one of Tan No Keah’s four sons, according to oral accounts provided by her aunt and grandmother in May 2002. ↩

-

C B Buckley, An Anecdotal History of Old Times in Singapore (Singapore: Oxford University Press, 1984), 254. (Call no. RSING 959.57 BUC) ↩

-

AME 902, 1525–30, 2 August 1853. ↩

-

AME 904/217, 20 February 1861; 904/255, 5 November 1861. ↩

-

AME 904/246, 20 July 1861. The land granted was most likely within the vicinity of the Johore town, Johore Bahru. ↩

-

Augustine Perie, Souvenirs De Malasie, Onze Ans Sous L’equateur (France: E. Delsaud, 1885), 19. ↩

-

Perie, Souvenirs De Malasie, 23. ↩

-

Perie, Souvenirs De Malasie, 24. ↩

-

Perie, Souvenirs De Malasie, 26. ↩

-

C. M. Turnbull, Straits Settlements, 1826–67 (London: Athlone Press, 1972), 152. (Call no. RSING 959.57 TUR) ↩

-

Perie, Souvenirs de Malasie, 25. ↩

-

Register, St Francis Xavier’s Chapel, Pontien, 1864–1873. ↩

-

The Straits Calendar and Directory, 1870, 16. ↩

-

AME 905/97, 10 January 1878. ↩

-

AME 905/236, 14 September 1881. ↩

-

Compte Reudu, Malaisie, 1882, 82–86. ↩

-

AME 905/304, 21 July 1883. ↩

-

AME 905/342, 1884. ↩

-

AME 905/236, 14 September 1881. ↩

-

Graham Saunders, Bishops and Brookes: The Anglican Missions and the Brooke Raj in Sarawak, 1848–1941 (Singapore: Oxford University Press, 1992), 28 (Call no. RSEA 959.522 SAU); See AME 904/217, 20 February 1861. ↩