Rising Dragon, Crouching Tigers? Comparing the Foreign Policy Responses of Malaysia and Singapore

What do states do when faced with an increasingly stronger and/or potentially threatening big power? For decades, mainstream international relations theorists have offered two broad answers to this central question: states are likely to either balance against or bandwagon with that power.

Introduction: Balancing, Bandwagoning or Hedging?

What do states do when faced with an increasingly stronger and/or potentially threatening big power?1 For decades, mainstream international relations (IR) theorists have offered two broad answers to this central question: states are likely to either balance against or bandwagon with that power. The “balancing” school argues that, driven to preserve their own security, states are likely to perceive a rising power as a growing threat that must be counter-checked by alliance and armament.2 This is particularly so if the power’s aggregate capability is accompanied by geographical proximity, offensive capability and offensive intentions.3 The “bandwagoning” school, by contrast, opines that states may choose to crouch under – rather than contain – a fast emerging great power. That is, they may choose to accept a subordinate role to the dominant power in exchange for material or ideational gain. This could happen when they view the power as a primary source of strength that can be exploited to promote their own interests.4

Not withstanding the enduring centrality of these schools of thought in the study of IR, recent scholarly debates suggest that these propositions might not accurately describe the contemporary responses of East Asian states toward a rising China.5 Empirical observations indicate that none of the regional states have adopted pure forms of balancing or bandwagoning. While most of them do pursue some form of military cooperation with Western powers (most notably the United States), these actions do not strictly constitute a balancing strategy toward China. This is because such cooperation actually predated the rise of China,6 and there is no clear indication that the states’ military modernisation has accelerated in tandem with the growth of Chinese power.7

In a similar vein, while East Asian states have all demonstrated an interest in developing economic ties and engaging China bilaterally and multilaterally, this should not be considered a bandwagoning strategy. Economic cooperation and diplomatic engagement are chiefly motivated by the pragmatic incentives of gaining economic and diplomatic profits and do not by themselves constitute an acceptance of power.8 Bandwagoning, in contrast, reflects a readiness on the part of smaller partners to accept the larger partner’s power ascendancy, mostly through political and military alignment. Empirically, however, none of the regional states (with the partial exceptions of Burma, Cambodia, and North Korea) have aligned politically and militarily with China.

There are several factors that explain why most regional states have rejected pure-balancing and purebandwagoning.9 Pure-balancing is considered strategically unnecessary, because the Chinese power remains largely a potential, rather than actual threat. It is also viewed as politically provocative and counter-productive, in that an anti-Beijing alliance would certainly render China hostile, turning a perceived threat into a real one. Further, it is regarded as economically unwise, as it would likely result in the loss of trade opportunities that could be reaped from China’s growing market. Pure-bandwagoning, on the other hand, while economically appealing, is deemed politically undesirable and strategically risky, as it is likely to limit the smaller states’ freedom of action.

For these reasons, most of the East Asian states do not regard pure-balancing and pure-bandwagoning as viable options. In the case of the original member countries of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), none of the tigers have chosen to contain or crouch under the dragon. Instead, they have taken a middle position that is now widely described as “hedging”.10 Borrowed originally from finance, “hedging” is brought into IR to refer to an alternative state strategy distinguishable from balancing and bandwagoning. It has been used not only to describe smaller states’ reactions to a major power but also big powers’ strategies in dealing with one another.11

This article examines the former, with case studies of Malaysia and Singapore. By comparing their foreign policies towards a rising China in the post-Cold War era, it seeks to analyse how and why these smaller states have responded to their giant neighbour the way they have.

Hedging: A Conceptual Framework

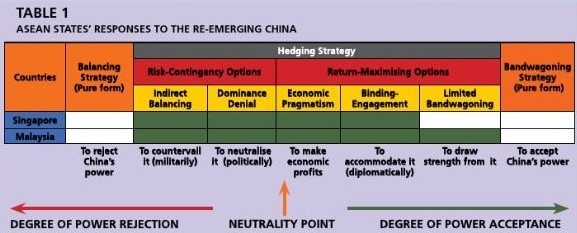

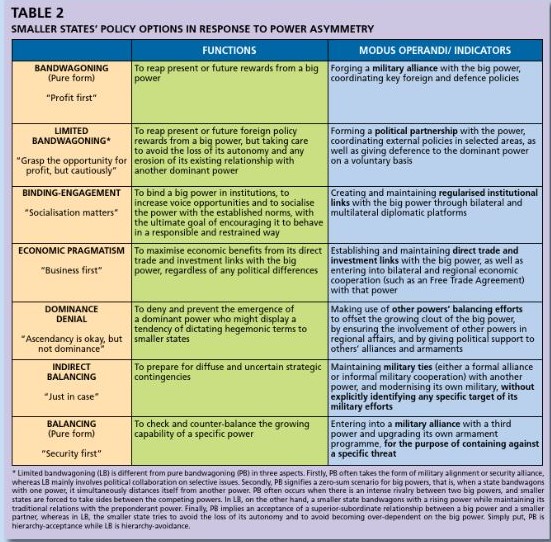

The hedging strategy is defined here as a purposeful act in which a state seeks to insure its long term interests by placing its policy bets on multiple counteracting options that are designed to offset risks embedded in the international system.12 Accordingly, it is conceived as a multiple-component strategy situated between the two ends of the balancing-bandwagoning spectrum (see Table 1).13 This spectrum is measured by the degrees of rejection and acceptance on the part of smaller state toward a big power, with pure balancing representing the highest degree of power rejection, and pure bandwagoning the extreme form of power acceptance.

In the context of Southeast Asia-China relations, hedging has five components: economic-pragmatism, bindingengagement, limited-bandwagoning, dominance-denial and indirect-balancing. Each of these components is distinguished not only by the degrees of power rejectionacceptance, but also by function and modus operandi (see Table 2).14

Hedging is essentially a two-pronged approach that operates by simultaneously pursuing two sets of mutually counteracting policies, which can be labelled as “returnmaximising” and “risk-contingency” options. The first set (consisting of economic-pragmatism, binding-engagement, and limited-bandwagoning) allows the hedger to reap as many economic, diplomatic and foreign policy profits as possible from the dominant power when all is well. This is counteracted by the risk-contingency set, which, through dominance-denial and indirect-balancing, limits the hedger’s loss if things go awry. Hedging, in essence, is a strategy that aims for the best and prepares for the worst. A state policy that focuses on merely return-maximising without preparing for risk contingency – and vice versa – is not a hedging strategy.

By concurrently adopting these risk-contingency and return-maximising options, smaller states such as Singapore and Malaysia hope to hedge against any possible risks associated with the rise of China and the resultant changes in the distribution of global power. Whether China will become weak and no longer be a potential, alternative power centre; whether Beijing will turn aggressive and become a target for containment by the U.S. and its allies; and whether China will grow even more stronger and gradually emerge as a key provider of regional public goods – the smaller states hope that their present strategy of counteracting one transaction against another will serve to insure their long term interests amid the structural change in the international system.15

This conceptualisation provides useful parameters to illuminate the similarities and differences between responses of the two ASEAN states. Our research findings indicate that while Malaysia and Singapore have both pursued a hedging strategy through economic pragmatism, binding-engagement, dominance-denial and indirect balancing, they have reacted differently toward limited bandwagoning. While Malaysia, has embraced the policy by showing a greater deference to China and collaborating on several foreign policy issues, Singapore, has dismissed limited bandwagoning as a policy option because of its concerns over geopolitical complexity and the long-term ramifications of a powerful China.

These similarities and differences are illustrated in Table 1 below.

Malaysia’s China Policy

The evolution of Malaysia’s China policy illustrates how a previously hostile and distrusting relationship has transformed into a cordial political partnership over a short period of time.16 As late as the second half of the 1980s, Malaysia still perceived China as a long-term threat, largely because of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP)’s continued support for the outlawed Communist Party of Malaya (CPM), and because of Beijing’s Overseas Chinese policy and the overlapping territorial claims in the South China Sea.17 Malaysia’s China policy then was understandably highly vigilant, cautiously designed to “manage and control” what was considered to be the “most sensitive foreign relationship.”18

After the end of the Cold War, however, Malaysia adopted a much more sanguine outlook towards China. The dissolution of the CPM in 1989 effectively removed a long-standing political barrier. At the same time, the growing salience of economic performance as a source of authority for the United Malays National Organisation (UMNO)-led coalition government, along with Prime Minister Mahathir’s foreign policy aspirations in the post-Cold War era, all contributed to the shift in Malaysia’s perception of China from being the largest security threat to that of a key economic and foreign policy partner.19 Such a perceptual change led to an adjustment in actual policy. In addition to strengthening its long-held economic pragmatism, Malaysia gradually adopted policies that can be considered binding-engagement and limited bandwagoning toward the second half of the 1990s.

Malaysia’s economic pragmatism is best illustrated by its leaders’ high-level visits to China, which have always been accompanied by large business delegations. These visits often resulted in the signing of memoranda of understanding for various joint projects. Former Premier Mahathir made seven such visits during his tenure, while the current Prime Minister Abdullah Badawi’s visit to China in May 2004 was his first bilateral visit to a non-ASEAN country after assuming his premiership. Presently, China is Malaysia’s fourth largest trading partner. Bilateral trade has increased more than eight-fold over the past decade, from US$2.4 billion in 1995 to US$19.3 billion in 2004.20

Binding-engagement is apparent in Malaysia’s various diplomatic efforts to increase dialogue opportunities withChina. Having become the first ASEAN state to forge diplomatic ties with Beijing during the Cold War, Malaysia was also among the first regional states to establish a bilateral consultative mechanism between foreign ministry officials in the immediate post-Cold War era, as early as April 1991.21 Kuala Lumpur has also tried to bind China at the regional stage. China’s appearance at the 24th ASEAN Ministerial Meeting in July 1991 as a guest of Malaysian government was Beijing’s first multilateral encounter with the regional organisation.

After the mid-1990s, Malaysia’s China policy gradually manifested elements of limited-bandwagoning. This was first apparent in the Spratly Islands dispute. According to Joseph Liow, Malaysia and China reached a consensus in October 1995 that rejected outside interference or third party mediation in the dispute. Since then, it appeared that Malaysia “was willing to accommodate and accept, if not share in, China’s positions on the South China Sea.”22 Not only did Malaysia echo the long-held Chinese assertion that territorial disputes should be addressed bilaterally, the two countries also seemed to take similar stance over the proposed code of conduct in the South China Sea.23 In August 1999, while Manila vehemently protested Kuala Lumpur’s construction of structures on Terumbu Siput and Terumbu Peninjau, Beijing response was mild. Considering the fact that the Malaysian Foreign Minister was in Beijing just before the construction took place, “it is a matter of conjecture,” a well-informed Malaysian analyst writes, whether the minister was “actually dispatched to Beijing in order to ‘explain’ the latest development over Malaysia’s position.”24

Malaysia’s limited-bandwagoning behaviour is particularly apparent in the area of East Asian cooperation. Partly due to the shared worldview between the leaders of the two countries, and partly because of Beijing’s international influence, Malaysia considers China as valuable partner in pushing for its goal of fostering closer and institutionalised cooperation among the East Asian economies. This goal can be traced back to Mahathir’s East Asian Economic Grouping (EAEG) proposal in December 1990, which advocated the protection of regional countries’ collective interests in the face of trade protectionism in Europe and North America. The proposal involved ASEAN members, Indochinese states and Northeast Asian countries, but excluded the U.S. and its Australasian allies. The EAEG concept was met with strong objection by the U.S., while receiving lukewarm responses from Japan, South Korea, and other ASEAN members, even when it was later renamed East Asian Economic Caucus (EAEC). Malaysia was disappointed with Japan’s response as it originally hoped that Tokyo would play the leading role in the proposed group.25 In due course, China stood out as the only major power who lent explicit support to EAEC despite its initial hesitance.26

In 1997, China, along with Japan and South Korea, accepted ASEAN’s invitation to attend an informal meeting during the ASEAN Summit in Kuala Lumpur, against the backdrop of the Asian financial crisis.27 The Summit was subsequently institutionalised as an annual cooperative mechanism among the East Asian economies, and marked the advent of the ASEAN Plus Three (APT) process. In 2002, Malaysia’s attempt to set up an APT Secretariat in Kuala Lumpur was opposed by some ASEAN members, but supported by Beijing.28

Malaysian and Chinese leaders clearly saw eye to eye on the need to accelerate East Asian cooperation and community building. In 2004, when Malaysian Prime Minister Abdullah proposed to convene the first East Asia Summit (EAS) in the following year, he was strongly backed by Chinese Premier Wen Jiabao. In the run-up to the inaugural meeting, Kuala Lumpur and Beijing initially wanted to limit the EAS membership to the 13 APT countries. Later, when it became clear that India, Australia and New Zealand would be included in the new forum, both Malaysia and China proposed that the APT would be the main vehicle for East Asia community building, and the EAS a forum for dialogue among the regional countries.

Beyond East Asian cooperation, the two countries have also concurred with each other over a host of regional and international issues, ranging from the welfare of developing countries to the pursuit of a multi-polar world.

The convergence of interests over these foreign policy issues, combined with the tangible benefits accruing from closer bilateral economic ties, somewhat assuaged the Malaysian leaders their earlier apprehensions about the potential ramifications of their powerful neighbour. At an event celebrating the 30th anniversary of bilateral relations, Prime Minister Abdullah remarked: “Malaysia’s China policy has been a triumph of good diplomacy and good sense. … I believe that we blazed a trail for others to follow. Our China policy showed that if you can look beyond your fears and inadequacies, and can think and act from principled positions, rewards will follow [emphasis added].”29

Taking this stance, leaders from Mahathir to Abdullah have made efforts to reiterate and internalise Malaysia’s benign view of Beijing at various occasions, often citing example of Chinese navigator Zheng He’s peaceful voyages to the Sultanate of Malacca in the 15th century to underscore the benevolent nature of Chinese power. Thus far, the leaders’ open rhetoric has largely been matched by the country’s policy. Notwithstanding the lingering concerns over Chinese long-term intentions within the Royal Malaysian Armed Forces (MAF) circle, there has been no clear indication of Malaysia pursuing internal or external balancing acts against China. An empirically-rich study on the bilateral relations suggests that Malaysia’s defence modernisation program does not reflect a strategic priority that is targeted at China.30

To be sure, Malaysia has long maintained close defence ties with the U.S, and has been a participant in the FivePower Defence Arrangement (FPDA) that involves the U.K., Australia, New Zealand and Singapore.31 These arrangements, however, should be seen as a manifestation of “indirect” rather than pure balancing, given that their raison d’etre had more to do with the need to cope with diffuse strategic uncertainty than with a specific threat. According to Amitav Acharya, Malaysia’s existing military ties with the West were created during the Cold War and therefore “might not be seen as a response to the rise of Chinese power.”32 This is certainly true for Malaysia’s security cooperation with the U.S.. As Malaysian scholar Zakaria Haji Ahmad observed:“…[in] Malaysian conceptions of the future, there is no notion of the U.S. being a strategic partner to ‘balance’, counter or neutralise China’s ‘big power’ mentality and actions.”33

To Malaysian leaders, the idea of a China threat could prove a self-fulfilling prophecy. As Mahathir once remarked: “Why should we fear China? If you identify a country as your future enemy, it becomes your present enemy – because then they will identify you as an enemy and there will be tension.”34 In this regard, the defence cooperation Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) signed by Malaysia and China in September 2005 was significant not only because it institutionalised the bilateral defence ties, but also because it signified that Malaysia was now more willing to see China as a security partner than a security threat.

That limited-bandwagoning has become part of Malaysia’s China policy does not imply that Malaysia favours a Beijing-dominated regional order. In fact, dominancedenial continues to be an unwavering goal for Malaysia, as indicated by the country’s efforts to maintain close relations with all powers. Deputy Prime Minister Najib Razak recently remarked that acceptance of the reality of China’s rise was “by no means a reflection of (Malaysia’s) fatalism, nor did it indicate that Malaysia was adopting a subservient position towards China.”35 Given Malaysia’s sensitivity about sovereignty and equality, along with the complexity of its domestic ethnic structure – that is, the long-standing uneasy relations between the majority ethnic Malays and the minority ethnic ]Chinese - it seems reasonable to expect that Malaysia’s bandwagoning behaviour will remain limited in the foreseeable future.

Singapore’s China Policy

The peculiarity of Singapore’s China policy is that it is an ambivalent one – warm in economic and diplomatic ties but distanced in political and strategic spheres.36 Specifically, while it concurs with Malaysia about the expediency of economic pragmatism and binding-engagement in dealing with China, it has firmly rejected limited-bandwagoning as an option.

Economic gain has always been a key driving force behind Singapore’s China policy. As far back as the 1960s and through the 1980s, Singapore, under the leadership of the People’s Action Party (PAP), already pursued an economically opportunistic policy notwithstanding political differences. The island-state actively promoted bilateral economic relations, especially after the signing of the bilateral trade agreement in December 1979 as well as the exchange of trade representatives in July 1981. The launch of China’s open-door policy in 1978, together with Singapore’s economic recession in the mid-1980s and the PAP’s plan to develop a “second wing” of the Singaporean economy, provided additional incentive for Singapore to exploit growing opportunities in China.37 Largely because of the complementary nature of the two economies, Singapore has long been China’s largest trading partner in ASEAN. Apart from trade, the close bilateral economic cooperation has also taken the forms of direct investment and management skills transfer. A case in point is the flagship Suzhou Industrial Park (SIP) project.

Singapore’s economic opportunism persisted through the post-Cold War era. Its initial objective of economic gain, however, was now meshed with the goal of engagement. Involving other ASEAN partners, Singapore’s engagement policy is implemented both through economic incentives and regional institutions such as the ASEAN Regional Forum (ARF).38 By binding Beijing in a web of institutions, Singapore – the prime advocate of engagement policy – hopes to give China a stake in regional peace and stability.39 As Evelyn Goh notes: “Singapore wants to see China enmeshed in regional norms, acting responsibly and upholding the regional status quo.”40

Why does Singapore care so much about the regional status quo, and how China is factored in? To begin with, Singapore is a tiny state with an acute sense of vulnerability.41 This could be attributed to its minuscule size, limited natural resources, demographic structure and geopolitical circumstances.42 As Michael Leifer observed, Singapore has since 1965 addressed its vulnerability with a three-fold approach: the promotion of economic interdependence, pursuit of armament and alliance, and cultivation of a balance of power at the regional level.43 Each of these approaches is in turn subject to the following pillars of “regional status quo-ness”: regional peace and stability, freedom and safety of sea-lanes, a cohesive ASEAN and a stable distribution of power. For instance, if there was no safe and free navigation of commercial vessels, Singapore’s economic viability would be severely affected; if ASEAN was weak and fractured, Singapore would not be able to play a disproportionate role in external affairs; and if there was no stable balance of power, Singapore’s autonomy would be compromised by the emergence of a dominant power that was likely to limit the strategic manoeuvrability of smaller states.

This explains Singapore’s concerns over the Taiwan Strait, the Spratlys and Beijing’s escalating power. Given its high dependence on maritime trade and sea-lanes of communication, Singapore becomes apprehensive whenever there is any rising tension in the Taiwan Strait. During the 1996 crisis, Singaporean officials feared that any armed conflict in the region would “totally destabilise foreign trade and investment.”44 Similarly, although Singapore is not a claimant to the Spratlys, it is concerned that the dispute will have a direct bearing on the safety of navigation in the South China Sea.45 Moreover, the Spratlys case illustrates the extent to which China is willing to abide by regional norms and international law.

To Singapore, there is little doubt that China will be powerful enough to alter the strategic landscape of Asia. The question, however, is less about capability than intention – that is how a robust China will exercise its newfound power in the region.

In view of the uncertainty over Beijing’s intentions, Singapore has cautiously adopted indirect-balancing as a “fallback position” should engagement policy fail.46 Such a position is very much a reflection of a “classic anticipatory state”, as described by Yuen-Foong Khong thus: “the time frame for Singapore’s ruminations about China is not now, or even five years down the line; it is twenty to thirty years hence.” PAP leaders therefore tend to “think in terms of possible scenarios for the future and how they might affect Singapore.”47 Given its relatively geographical distance from China, as well as the absence of territorial disputes, China does not pose any direct threat to the citystate. Singapore’s musings about China thus are mostly cast over the mid- and long-term, and revolve around whether Beijing’s behaviour will disrupt regional stability and prosperity, constrain Singapore’s policy choices or drive a wedge between Southeast Asian states that would undermine ASEAN cohesion.48

Singapore’s quintessence as an anticipatory state is clearly demonstrated by a decision made by then Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew in the immediate post-Cold War era. In August 1989, when it appeared that the U.S. might have to close the Clark and Subic bases in the Philippines, Singapore announced that it would grant the Americans access to its bases. Lee’s move was driven by his fear that the U.S. withdrawal would create a power vacuum in the Asia Pacific, which would lead to competition and conflict among regional powers seeking to fill the vacuum. If that happened, the ensuing instability would threaten Singapore’s survival. To forestall this, Lee decided to “stick with what had worked so far,” i.e. the American military presence that he saw as “essential for the continuation of international law and order in East Asia.”49 While Lee’s decision addressed strategic uncertainty in general rather than China in particular, Beijing’s subsequent action over the Mischief Reef a few years later gave rise to the strategic uncertainty he was worried about. In 1998, Singapore further strengthened bilateral security ties with the U.S. by constructing a new pier at its Changi Naval Base, designed specially to accommodate U.S. aircraft carriers.

While Singapore’s indirect-balancing has relied primarily on its military cooperation with the U.S., it would be wrong to link Singapore-U.S. ties entirely to China. In fact, Singapore’s recent efforts to solidify its collaboration with the U.S. have less to do with China than with its new concerns over terrorism. According to Evelyn Goh, Singapore’s concept of security changed significantly after the September 11 terrorist attacks in the U.S. and the arrest of members of the Jemaah Islamiah (JI) group in Singapore in 2002. Terrorism has now been identified as the key security threat. Consequently, the new counter-terrorism agenda now acts “as stronger glue for the Singapore-U.S. strategic partnership than the China challenge.”50

Such developments, however, do not mean that China has been relegated to the sidelines of Singapore’s strategic concerns. In fact, despite Beijing’s charm diplomacy in recent years, Singapore still cautiously guards against any potential repercussions of an increasingly powerful China. As Goh Chok Tong remarked in 2003: “China is conscious that it needs to be seen as a responsible power and has taken pains to cultivate this image. This is comforting to regional countries. Nevertheless, many in the region would feel more assured if East Asia remains in balance as China grows. In fact, maintaining balance is the over-arching strategic objective in East Asia currently, and only with the help of the U.S. can East Asia achieve this.”51 In this context, the Sino-Singaporean diplomatic feud that erupted right after Lee Hsien Loong’s visit to Taipei in 2004 might have heightened Singapore’s trepidation about the possible ramifications of a too powerful China.

Finally, Singapore’s policy is also marked by its rejection of limited-bandwagoning. This is owing to its demographic profile and geopolitical complexity. Ever since Singapore gained independence after its unpleasant separation from the Federation of Malaysia in 1965, the island, with an ethnic Chinese population of 76 percent, has been reluctant to be seen as the “third China,” especially by its larger neighbours, Malaysia and Indonesia. During the Cold War, Singapore’s declaration that it would be the last ASEAN state to establish diplomatic ties with Beijing was intended to dispel the image that it would be the “front post of China”.52 Even after the end of the Cold War, Singapore still takes care to downplay ethnic affinity in its bilateral relations with China, and to avoid leaving any impression that it is promoting China’s interests in the region.53 For this reason, Singapore set “a self-imposed limit” on the extent to which it can forge political ties with Beijing.54 Hence, bandwagoning behaviour, even in limited form, does not appear to be a likely option for Singapore.

Conclusion: Explaining the Policy Variation

The preceding discussions suggest that the variation in Malaysia’s and Singapore’s responses to the rise of China is largely a function of the differing pathways of domestic authority consolidation, i.e. the differing sources through which the respective ruling elites seek to enhance their authority to rule at home.

In the case of Malaysia, the substance of its China policy mirrors the key sources of the UMNO-led government’s political foundation. These include the promotion of Malay ethnic dominance, economic growth, electoral performance, national sovereignty and international standing. Pursuing a pure form of bandwagoning (an across-the-board alignment and an acceptance of hierarchical relations) is a non-starter for the Malay-dominated regime, as this option would likely result in an imbalance in domestic political configuration and an erosion of external sovereignty. The limited form of bandwagoning, however, is desirable and vital, for the Barisan Nasional (BN) coalition government. Given Malaysia’s multi-racial structure, any politically significant economic performance requires the ruling BN to concurrently attain two goals: the improvement of the Malays’ economic welfare, and the enlargement of the overall economic pie for the non-Malay groups.55 In this regard, a closer relationship with Beijing is crucial for Malaysia not only because it boosts the bilateral trade and investment flows, but also because China’s support will strengthen Malaysia’s ability to promote a new economic order for East Asia, with the ultimate goal of reducing the effects of the volatile global economy on its national economic performance. This ambition, if realised, is expected to elevate Malaysia’s regional and international standing, which along with other legitimation pathways would help consolidate its electoral base. Hence, a pure form of balancing against Beijing is not only unjustifiable, but would prove harmful to BN regime interests because such an option would call for a full-fledged alliance with the U.S., which would in turn reduce the credibility of the BN’s claim of pursuing an “independent” external policy for Malaysia.

In the case of Singapore’s China policy, the rejection of limited-bandwagoning despite the enthusiasm for bindingengagement and economic-pragmatism is best explained by the very foundation of the PAP elite’s political power, i.e. the imperative to cope with the island-state’s inherited vulnerability. Singapore’s close economic and diplomatic relations with China would serve to attain this goal (by contributing to Singapore’s sustainable economic vitality and its external stability), but a strict sense of political and strategic partnership would not. In fact, any bandwagoning polices with China would only increase Singapore’s vulnerability by causing its two larger neighbours to be suspicious. For a “little red dot” that has been viewed as a Chinese island in a Malay sea, such a scenario is likely to destabilise Singapore’s immediate external environment and divert the attention of the PAP elite away from more crucial domestic economic tasks.

An inference can be drawn from the above analyses: how a smaller state is attracted to or alarmed by the aggregate capability of a rising power depends primarily on the state’s distinctive sources of domestic authority consolidation. To the extent that the pathways of regime consolidation require the state elite to utilise opportunities provided by the growing ascendancy of a big power, and to the extent that the power’s actions help rather than hinder the consolidation process, then the state (as in the case of Malaysia) would stress return-maximising more than risk-contingency measures vis-à-vis the power. However, if the pathways of a regime’s authority consolidation are not entirely compatible with the rise of a power, and if the power’s actions further complicate that legitimation process, then the state is expected to place more emphasis on risk-contingency options, as in the case of Singapore’s China policy.

This study is significant for policy analysis. Given the fact that few states are adopting pure forms of balancing or bandwagoning vis-à-vis China, conceptualising the hedging strategy as a spectrum of policy options is a more realistic way to observe the change and continuity in policy choices of states over time. It allows policy analysts to ponder the possibility, direction, and conditions of a horizontal shift along the building blocks of the spectrum – for instance, from indirect balancing leftward to pure-balancing, or from limited-bandwagoning rightward to pure-bandwagoning. Considering that states are more likely to adjust their strategic posture gradually, such a “transitional” outlook would be useful in monitoring the vicissitudes of states’ alignment choices amid the emerging structural changes in the 21st century.

Lee Kong Chian Research Fellow

National Library

NOTES

-

The author is grateful to Karl Jackson, David Lampton, Francis Fukuyama, Bridget Welsh, Wang Gungwu, Zakaria Haji Ahmad, Kong Bo, Goh Muipong, Jessica Gonzalez and Laura Deitz for their helpful comments on earlier drafts of this essay. All shortcomings of the paper are entirely the author’s own. ↩

-

Kenneth N. Waltz, Theory of International Politics (Mass.: Addison-Wesley, 1979) ↩

-

Stephen M. Walt, “Alliance Formation and the Balance of World Power,” International Security 9, no. 4 (Spring 1985): 3–43. (From JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website) ↩

-

Randall L. Schweller, “Bandwagoning for Profit: Bringing the Revisionist State Back In,” International Security 19, no. 1 (Summer 1994): 72–107 (From JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website); Kevin Sweeney and Paul Fritz, “Jumping on the Bandwagon: An Interest Based Explanation for Great Power Alliances,” Journal of Politics 66, no. 2 (May 2004): 428–49. ↩

-

Alastair Iain Johnston and Robert Ross, eds., Engaging China: The Management of an Emerging Power (New York: Routledge, 1999) (Call no. RSING 327.09509045 ENG); David C. Kang, “Getting Asia Wrong: The Need for New Analytical Frameworks,” International Security 27, no. 4 (Spring 2003): 57–85; Amitav Acharya, “Will Asia’s Past Be Its Future?” International Security 28, no. 3 (Winter 2003/2004): 149–64. (From JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website) ↩

-

Amitav Acharya, “Containment, Engagement, or Counter Dominance? Malaysia’s Response to the Rise of China,” in Engaging China: The Management of an Emerging Power, ed. Alastair Iain Johnston and Robert Ross (New York: Routledge, 1999), 140. (Call no. RSING 327.09509045 ENG) ↩

-

Herbert Yee and Ian Storey, eds., The China Threat: Perceptions, Myths and Reality (London: RoutledgeCurzon, 2002) (Call no. RUR 327.51 CHI); Evelyn Goh, ed., Betwixt and Between: Southeast Asian Strategic Relations with the U.S. and China, IDSS Monograph No. 7 (Singapore: Institute of Defence and Strategic Studies, 2005). (Call no. RSING 327.59051 BET) ↩

-

Amitav Acharya has rightly cautioned that engagement cannot be viewed as bandwagoning “because it does not involve abandoning the military option vis-à-vis China”, and that economic self-interest should not be confused with bandwagoning because economic ties “do not amount to deference.” See Acharya, “Will Asia’s Past Be Its Future,” 151–2. ↩

-

This is not to say that the balancing and bandwagoning propositions are no longer relevant. Rather, it only reflects that balancing and bandwagoning do not prevail because the antecedent conditions of these behaviours are largely absent in the present world. These conditions are, inter alia, (a) an all-out rivalry among the great powers which compels smaller states to choose sides; (b) political faultlines that divide states into opposing camps; and (c) strategic clarity. ↩

-

Johnston and Ross, Engaging China; Chien-Peng Chung, “Southeast Asia-China Relations: Dialectics of ‘Hedging’ and ‘Counter-Hedging’,” Southeast Asian Affairs (2004): 35–53 (From JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website); Evelyn Goh, Meeting the China Challenge, Policy Studies Series no. 16 (Washington, DC: East West Center Washington, 2005) (Call no. RSEA 327.59051 GOH); Francis Fukuyama and G. John Ikenberry, “Report of the Working Group on Grand Strategic Choices” (The Princeton Project on National Security, September 2005), 14–25. ↩

-

For instance, Evan S. Medeiros, “Strategic Hedging and the Future of Asia-Pacific Stability,” The Washington Quarterly no. 1 (Winter 2005): 145–67; Rosemary Foot, “Chinese Strategies in a US-Hegemonic Global Order: Accommodating and Hedging,” International Affairs 82, no. 1 (2006): 77–94. (From JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website) ↩

-

This definition is adapted from Glenn G. Munn et al., Encyclopedia of Banking and Finance, 9th ed. (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1991), 485; Jonathan Pollack, “Designing a New American Security Strategy for Asia,” in Weaving the Net: Conditional Engagement with China, ed. James Shinn (New York: Council on Foreign Relations, 1996), 99–132 (Call no. RUR 327.73051 SHI); Goh, Meeting the China Challenge, 2–4. ↩

-

The need to go beyond the dichotomous terms was emphasized earlier by Amitav Acharya and Ja Ian Chong. See Amitav Acharya, “Containment, Engagement, or Counter-Dominance?” and Chong Ja Lan, Revisiting Responses to Power Preponderance (Institute of Defence and Strategic Studies Working Paper Series no. 54) (Singapore: Institute of Defence and Strategic Studies, 2003) (From PublicationSG). These writings, however, have seemed to privilege one single “prime” policy on a multi-option continuum, thus overlooking the fact that smaller states may and often choose to adopt more than one policy option simultaneously in responding to a rising power. ↩

-

For a more detailed account on each of these policy options, see Kuik Cheng-Chwee, “Regime Legitimation and Foreign Policy Choices: A Comparative Study of Southeast Asian States’ Hedging Strategies toward a Rising China, 1990–2005” (dissertation prospectus submitted to Paul H. Nitze School of Advanced International Studies (SAIS), Johns Hopkins University, Washington, D.C., September 2006) ↩

-

By contrast, states that pursue pure balancing or pure band wagoning are likely to face entirely different outcomes, depending on the changes in power structure. That is, they will be in a favourable position if the power they choose to bet on eventually prevails. Conversely, they will be in an unfavourable position if the power they choose to take sides with is vanquished by another competing power. ↩

-

Abdul Razak Baginda, “Malaysian Perceptions of China: From Hostility to Cordiality,” The China Threat: Perceptions, Myths and Reality, ed. Herbert Yee and Ian Storey (London: RoutledgeCurzon, 2002), 227–47 (Call no. RUR 327.51 CHI); Shafruddin Hashim, “Malaysian Domestic Politics and Foreign Policy: The Impact of Ethnicity,” in ASEAN in Regional and Global Context, et al., ed. Karl D. Jackson (Berkeley: University of California, 1986), 155–62. (Call no. RSING 382.0959 ASE) ↩

-

Wang Gungwu, “China and the Region in Relation to Chinese Minorities,” Contemporary Southeast Asia 1, no. 1 (May 1979): 36–50; Stephen Leong, “Malaysia and the People’s Republic of China in the 1980s: Political Vigilance and Economic Pragmatism,” Asian Survey 27, no. 10 (October 1987): 1109–26. (From JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website) ↩

-

Chai Ching Hau, “Dasar Luar Malaysia Terhadap China: Era Dr Mahathir Mohamad [Malaysia’s Foreign Policy towards China: The Mahathir Mohamad’s Era] (master’s thesis, National University of Malaysia, 2000); James Clad, “An Affair of the Head,” Far Eastern Economic Review, 4 July 1985, 12–14. ↩

-

Joseph Chin Yong Liow, “Malaysia-China Relations in the 1990s: The Maturing of a Partnership,” Asian Survey 40, no. 4 (July–August 2000), 672–91 (From JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website); K. S. Nathan, “Malaysia: Reinventing the Nation,” in Asian Security Practice, ed. Muthiah Alagappa (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1998), 513–48. (Call no. RSEA 355.03305 ASI) ↩

-

“Trade and Investments Statistics,” Ministry of Investment, Trade and Investment, https://www.miti.gov.my. ↩

-

“30 Years of Diplomatic Relations,” United Malays National Organization, accessed 5 June 2004, Mohamad Sadik Kethergany, Malaysia’s China Policy, master’s thesis, Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia, 2001) ↩

-

Liow, “Malaysia-China Relations in the 1990s,” 691. ↩

-

Liow, “Malaysia-China Relations in the 1990s,” 686–9. ↩

-

Baginda, “Malaysian Perceptions of China, 244. ↩

-

Interviews with Malaysian diplomats and academia, January 2006 and February 2007. ↩

-

Stephen Leong, “The East Asian Economic Caucus (EAEC): ‘Formalized’ Regionalism Being Denied,” in National Perspectives on the New Regionalism in the South, et al., ed. Bjorn Hettne, vol. 3. (London: MacMillan, 2000) ↩

-

Richard Stubbs, “ASEAN Plus Three: Emerging East Asian Regionalism?” Asian Survey 42, no. 3 (May–June 2002), 443. (From JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website) ↩

-

Interviews with Malaysian Foreign Ministry officials, January 2006 and March 2007. ↩

-

Abdullah Haji Ahmad Badawi, “Keynote Address to the China Malaysia Economic Conference,” speech, Sunway Lagoon Resort Hotel, 24 February 2004, https://www.pmo.gov.my/ucapan/?m=p&p=paklah&id=2833. ↩

-

Liow, “Malaysia-China Relations in the 1990s,” 682–3. ↩

-

Mak Joon Nam, “Malaysian Defense and Security Cooperation,” in Asia Pacific Security Cooperation, ed. See Seng Tan and Amitav Acharya (London: M.E. Sharpe, 2004), 127–53. (Call no. RSING 355.031095 ASI) ↩

-

Acharya, “Containment, Engagement, or Counter-Dominance?”, 140. ↩

-

Zakaria Haji Ahmad, “Malaysia,” Betwixt and Between: Southeast Asian Strategic Relations with the U.S. and China, IDSS Monograph No. 7 (Singapore: Institute of Defence and Strategic Studies, 2005), 59. (Call no. RSING 327.59051 BET) ↩

-

“I am Still Here: Asiaweek’s Complete Interview with Mahathir Mohamad,” Asiaweek, 9 May 1997, http://edition.cnn.com/ASIANOW/asiaweek/97/0509/cs3.html. ↩

-

Mohd Najib Tun Abd Razak, “Strategic Outlook for East Asia: A Malaysian Perspective,” Keynote Address to the Malaysia and East Asia International Conference, Kuala Lumpur, 9 March 2006. ↩

-

Part of this section is drawn from Kuik Cheng-Chwee, “Shooting Rapids in a Canoe: Singapore and Great Powers,” in Impressions: The Goh Years in Singapore et al., ed. Bridget Welsh (Singapore: NUS Press, 2009). (Call no. RSING 959.5705 IMP) ↩

-

John Wong, The Political Economy of China’s Changing Relations with Southeast Asia (London: Macmillan, 1984) (Call no. RSING 338.9151059 WON); Chia Siow-Yue, “China’s Economic Relations with ASEAN Countries,” in ASEAN and China: An Evolving Relationship, ed. Joyce K. Kallgren, Noordin Sopiee, and Soedjati Djiwandono (Berkeley: University of California, 1988), 189–214 (Call no. RSING 327.51059 ASE); Lee Lai To, “The Lion and the Dragon: A View on Singapore-China Relations,” Journal of Contemporary China 10, no. 28 (2001), 415–25. ↩

-

Yuen Foong Khong, “Singapore: A Time for Economic and Political Engagement,” in Engaging China: The Management of an Emerging Power, ed. Alastair Iain Johnston and Robert Ross (New York: Routledge, 1999), 109–28. (Call no. RSING 327.09509045 ENG) ↩

-

Allen Whiting, “ASEAN Eyes China: The Security Dimension,” Asian Survey 37, no. 4 (April 1997) ↩

-

Evelyn Goh, “Singapore’s Reaction to a Rising China: Deep Engagement and Strategic Adjustment,” in China and Southeast Asia: Global Changes and Regional Challenges, ed. Ho Khai Leong and Samuel C. Y. Ku (Singapore and Kaohsiung: ISEAS & CSEAS, 2005), 313. ↩

-

Chan Heng Chee, “Singapore: Coping with Vulnerability,” in Driven by Growth: Political Change in the Asia-Pacific Region, ed. James William Morley and Thomas P. Bernstein (New York: M.E. Sharpe, 1993), 219–41. ↩

-

See Barry Desker and Mohamed Nawab Mohamed Osman, “S Rajaratnam and the Making of Singapore Foreign Policy,” in Kwa Chong Guan, ed., S Rajaratnam on Singapore: From Ideas to Reality, ed. Kwa Chong Guan (Singapore: World Scientific Publishing, 2006), 3–20. (Call no. RSING 327.5957 S) ↩

-

Michael Leifer, Singapore’s Foreign Policy: Coping with Vulnerability (New York: Routledge, 2000). (Call no. RSING 327.5957 LEI) ↩

-

Whiting, “ASEAN Eyes China,” 308. ↩

-

Ian Storey, “Singapore and the Rise of China,” in The China Threat: Perceptions, Myths and Reality, ed. Herbert Yee and Ian Storey (London: RoutledgeCurzon, 2002), 213. (Call no. RUR 327.51 CHI) ↩

-

Khong, “Time for Economic and Political Engagement,” 121. ↩

-

Khong, “Time for Economic and Political Engagement,” 113. ↩

-

Goh, Meeting the China Challenge, 13. ↩

-

Yuen Foong Khong, “Coping with Strategic Uncertainties,” in Rethinking Security in East Asia, ed. J. J. Suh, Peter J. Katzenstein, and Allen Carlson (Stanford: Stanford University, 2004), 181–2. (Call no. RUR 355.03305 RET) ↩

-

Goh, Meeting the China Challenge, 13–15. ↩

-

Goh Chok Tong, “Challenges for Asia,” speech, Research Institute of Economy, Trade and Industry (RIETI) Special Seminar, Tokyo, 28 March 2003. ↩

-

Leo Suryadinata, China and the ASEAN States: The Ethnic Chinese Dimension (Singapore: Marshall Cavendish Academic, 1985), 81. (Call no. RSING 327.59051 SUR) ↩

-

Khong, “Time for Economic and Political Engagement,” 119; Goh, “Singapore’s Reaction to a Rising China,” 216. ↩

-

Khong, “Time for Economic and Political Engagement,” 119. ↩

-

Liow, “Malaysia-China Relations in the 1990s,” 676. ↩