Picturing an Island Colony: A Short History of Photography in Early Singapore

Traces Singapore’s photographic history and highlights three specific titles relating to early Singapore’s photographic past.

Before embarking on a journey through time into the world of photography in mid-19th century Singapore, the birth of modern photography deserves a brief mention. Photography as it is understood and practised today – made possible by the scientific discovery of methods to permanently fixate images directly formed by light onto either metal or paper – did not come into being until the 19th century. Many writers conventionally hail Frenchman Louis-Jacques-Mande Daguerre (1787–1851) and William Fox Talbot (1800–1877) in Britain as the founding fathers of modern photography. Daguerre and Talbot were the first to announce their findings publicly in 1839, though they were certainly not alone in the quest to permanently capture fleeting images.1 Daguerre, after years of experimentation (much of it in collaboration with fellow contemporary Joseph-Nicephore Niepce, 1765–1833), had taken his first successful photograph in 1837, which he proudly named after himself – the Daguerreotype, though it would be another two years before his invention was publicly announced. William Talbot’s photographic process became known as the Calotype or Talbotype. His photographic technique, which became involved in the making of multiple positive prints from paper negatives, is significant because it paved the way for the development of modernday photography.2

It is not known for sure when photography first arrived in Singapore. The earliest known daguerreotypes of the settlement were created by a Frenchman named Jules Itier (1802–1877), who first set foot in Singapore in July 1844 as part of a French commercial mission to Asia. Besides recording his impressions of the British colony in a journal (which was subsequently published in Paris in 1848, entitled Journal d’un voyage en Chine en 1843, 1844, 1845, 1846), Itier also photographed the island, producing a number of quarter-plate (8.3 x 10.5) daguerreotypes of the town area, including that of the Singapore River from Government Hill (present-day Fort Canning). Today, this daguerreotype is part of the collection at the National Museum of Singapore.3

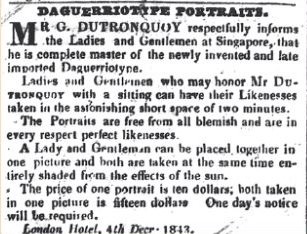

This photographic history of colonial Singapore begins with Gaston Dutronquoy, a native of Jersey,4 who arrived in Singapore in March 1839.5 Starting off as a portrait painter and miniaturist (his advertisement, dated 27 March 1839, first appeared in the weekly Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser on 11 April6), he is more popularly known as the proprietor of the London Hotel, which first opened at High Street in May 1839.7 It was in the London Hotel that Dutronquoy commenced his photographic business, first advertising himself as a daguerreotypist in the Singapore Free Press on 4 December 1843.

Dutronquoy’s assurance to potential customers that “a sitting can have their likenesses taken” in just two minutes was probably not exaggerated as by 1840, technical improvements made to the daguerreotype process had reduced exposure times from ten minutes to just one minute.8 Nevertheless, his advertisement is a little misleading, because it does not sufficiently inform patrons about the entire posing process, which certainly took longer than two minutes. A detailed description of a Daguerrian photoshoot provided by art historian Dr Naomi Rosenblum, based on an 1843 image entitled “Jabez Hogg making a portrait in Richard Beard’s studio”, gives readers an idea of what a Dutronquoy’s typical sitting in Dutronquoy’s studio might have been like:

A tripod – actually a stand with a rotating plate – supports a simple camera without bellows. It is positioned in front of a backdrop … The stiffly upright sitter [or sitters] … is [or are] clamped into a head-brace, which universally was used to ensure steadiness. He clutches the arm of the chair with one hand and makes a fist with the other so that his fingers will not flutter. After being posed, the sitter remains in the same position for longer than just the time it takes to make an exposure, because the operator must first obtain the sensitised plate from the darkroom (or if working along, prepare it), remove the focusing glass of the camera, and insert the plate into the frame before beginning the exposure … In all, the posing process was nerve-wrecking and lengthy, and if the sitter wished to have more than one portrait made the operator had to repeat the entire procedure, unless two cameras were used simultaneously – a rare occurrence except in the most fashionable studios.9

Some individuals who had their pictures taken at Dutronquoy’s daguerreotype studio might have shared the same sentiments as Ralph Waldo Emerson, an American author, poet and philosopher, who had this to say about posing in front of the camera:

In your zeal not to blur the image, did you keep every finger in its place with such energy that your hands became clenched as for fight or despair, and in your resolution to keep your face still, did you feel every muscle becoming every moment more rigid; the brows contracted into a Tartarean frown, and the eyes fixed in it, in madness, or in death? 10

Photography in 19th century Singapore was also done outdoors, though it is not known whether Dutronquoy provided such a service for customers wishing to have their pictures taken outside the studio. The Hikayat Abdullah, the autobiography of early 19th century Malay writer Abdullah Abdul Kadir (better known as Munshi Abdullah), gives a vivid eyewitness account of a daguerreotype being made by an unidentified American doctor on Bonham’s Hill (what is today Fort Canning Hill) in around 1841:

… I walked up the hill, and the others joined us there. I saw the doctor go into a room and bring out a box. The box had an attachment like a telescope. The lens, about the size of a cent piece, could be pulled outwards. It had two components, the larger one inside. This larger lens magnified anything seen in front of it. One side of the box could be opened and closed. Then the doctor went and fetched a metal plate about nine inches long by six inches wide, thin and brightly polished. He rubbed the surface with a certain kind of reddish-coloured powder until it was a dull brown all over. Then he took a bowl which had been filled with another kind of powder, black in colour. He held the polished plate about four inches above the powder. After about ten minutes he lifted up the plate, and its colour had turned to a reddish gold. He took the plate and put it into the extensible box, which he then placed with the side of the apparatus with a sliding lens in the direction in which he wished to take the picture. The image of the scene passed through the lens and struck the plate. He said, “In strong sunlight it takes only a moment, but in a dull light it takes a little longer.” After this he took the metal plate out and we noticed that there was nothing visible on it at the time. He then took it to a place in a shade and washed it with a chemical solution. Now he had a kind of frame with a vessel containing quicksilver fitted underneath it. He mounted the plate in position on top of the vessel, about six inches above the surface of the quicksilver. Below the vessel there was a spirit lamp which he lit. The quicksilver soon became hot and gradually its vapour rose and was allowed to condense on the plate for a certain length of time. Now the chemical with which the plate had been treated etched all the parts on which light had fallen, while it had not affected those parts on which no light had fallen. After a timed interval the plate was lifted out and at once we saw a picture of the town of Singapore imprinted on it, without deviation even by so much as the breadth of a hair, a fine reproduction of the actual scene. The plate with the picture on it was used as a block, and by contact with its surface prints were easily taken which faithfully reproduced the original without variation. 11

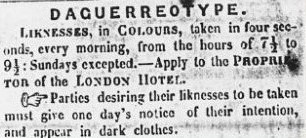

Another pioneer who worked with the daguerreotype camera was J. Newman, an American traveller who visited Singapore between 1856 and 1857. Although his stay in Singapore was short-lived, he played an important role in promoting the use of the daguerreotype in the settlement. As expressed by John Falconer, Newman’s advertising approach “is characterised by a much more positive and aggressive attempt to catch the public’s eye”.12 All in all, the daguerreotype proved to be much more popular than Talbot’s Calotype during the 1840s and 1850s. This was so in spite of the fact that the latter allowed multiple prints to be made from a single negative, a process not possible with the daguerreotype. One possible reason for this, Falconer explains, was that the daguerreotype was offered free-ofcharge to the world, while Talbot’s invention was patented (in 1840) and thus posed restrictions where its practice was concerned. In fact, Daguerre’s photographic technique was so well received internationally that his original pamphlet of instruction was translated into nine languages!13 Yet, in spite of its popularity, by the late 1850s, the daguerreotype was gradually replaced by another photographic technique, termed the wet collodion process, a paper print-based method invented commercially in Singapore by Edward A. Edgerton around 1858.

Perhaps the most renowned photographer in 19th century Singapore who made use of the wet collodion process was Scotsman John Thomson (1837–1921), who travelled extensively to many parts of Asia including Singapore. Judith Balmer provides a lucid description of what Thomson had to do to create a wet-plate collodion:

First, he composed the scene, then focused it on the groundglass screen. Next, he selected a perfectly clean, blemish-free glass plate (any marks showed up in the print) and, in the darkroom, evenly coated it with collodion. After waiting a few seconds for the collodion to set slightly, he sensitised the plate by immersing it in a bath of silver nitrate. He then put the coated plate in a light-tight wooden frame, and hurried out to the camera with it. Quickly he would recheck the focus on the ground-glass screen before replacing the screen with the frame and exposing the plate. After hurrying back to the darkroom, he removed the plate from its frame and continuously poured freshly made developing solution over the surface of the plate. When the image was sufficiently developed, he rinsed the glass plate with water and then chemically fixed it (if he did not properly fix the negative, the image would, over time, continue to darken when exposed to light). Finally, he washed the plate thoroughly to remove all traces of chemicals, and set it aside to dry. When dry, the negative could be packed away for printing later.14

John Thomson loved to work in the early mornings, which according to him was “the time when the finest atmospheric effects may be caught”. He had remarked, “The temperature is lower, and for an hour or two, nature enjoys the most perfect repose. … there is not a breath of wind to stir even the leaves of the ‘people’ [pipal] tree.”15 Given such a preference, it is not surprising why his “Coconut Plantation” in Singapore was taken in the early morning.

In retrospect, photography in Singapore was still in its nascent stage at the end of the 1850s, but it certainly marked the beginning of a development that would turn out to be revolutionary. Over the next few decades, photographic studios, most of them European-owned, sprang up throughout the British trading settlement, not only offering portraiture photographic services to the public but also providing an invaluable medium for capturing images of distant lands and Britain’s expanding presence in them through imperialism. Photography did not come to a standstill with the outbreak of the Second World War; Japanese war photographers and photo studios both played their part in enriching Singapore’s photographic record. The idea of photography as an art form began to take shape after the war, and continues to evolve to this day.

SELECTED TITLES ON THE HISTORY OF PHOTOGRAPHY IN EARLY SINGAPORE AVAILABLE AT THE LEE KONG CHIAN REFERENCE LIBRARY

The Lee Kong Chian Reference Library’s rich collection of heritage materials on Singapore includes a number of works related to the history of photography in early colonial Singapore. In his book entitled A Vision of the Past , John Falconer, Curator of Photographs in the British Library’s Oriental and India Office, concentrates on one European owned famous studio that operated during the late 19th and early 20th centuries – G.R. Lambert & Co. (first formed in 1867, when Singapore became a Crown Colony). The book also provides a pretty detailed account of photographic activities prior to 1867. His 190-oddpage masterpiece is replete with images of not just classic studio portraits but also photographs of lush landscapes, majestic architecture, and colourful street scenes throughout Singapore, Malaya and other parts of Southeast Asia, from the Lambert collection. In addition, Falconer’s inclusion of a biographical list of early photographers who operated in Singapore is an invaluable reference for any researchers interested in the beginning and evolution of photography in the then island colony.

All rights reserved, Times Edition, 1987.

All rights reserved, Times Edition, 1987.

Eminent travel photographer John Thomson recounted his travel experiences in his memoirs, which were subsequently published as The Straits of Malacca, Indo-China and China in 1875. The first six chapters of this work, which include his journey to Singapore, were reprinted by Oxford University Press in 1993. EntitledThe Straits of Malacca, Siam and Indo-China: Travels and Adventures of a Nineteenth-Century Photographer , it features a lucid introduction by Judith Balmer, outlining the life and achievements of the 19th century travel photographer.

All rights reserved, Oxford University Press, 1993.

All rights reserved, Oxford University Press, 1993.

It is worthy to note that apart from European studios, there were also those owned by Chinese. The Chinese owned photographic studios proliferated towards the end of the 19th century. One example of a prominent Chinese studio that operated in Singapore was Lee Brothers, whose photographic collection now resides mainly at the National Archives of Singapore. Gretchen Liu’s From the Family Album, tells the story of Lee King Yan, the founder of Lee Brothers Photographers (1911).

All rights reserved, Landmark Books, 1995.

All rights reserved, Landmark Books, 1995.

King Yan was later joined by his brother, Poh Yan, and the dynamic duo developed their studio into a frontrunner in the competitive world of portraiture photography. Gretchen Liu mentions that Lee Brothers photographed many of Singapore’s eminent personalities of the day; they included Dr Lim Boon Keng, Mr and Mrs Song Ong Siang, and even Dr Sun Yat-sen during his visit to Singapore. Liu added that a substantial number of the studio’s photographs were used for the 1923 classic biographical work,One Hundred Years of the Chinese in Singapore, compiled by Song Ong Siang.16

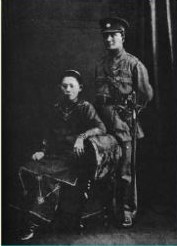

Portrait of Song Ong Siang and his wife, taken by Lee Brothers. Reproduced from One Hundred Years’ History of the Chinese in Singapore. All rights reserved, Murray, 1923.

Portrait of Song Ong Siang and his wife, taken by Lee Brothers. Reproduced from One Hundred Years’ History of the Chinese in Singapore. All rights reserved, Murray, 1923.

Reference Librarian

Lee Kong Chian Reference Library

National Library

REFERENCES

Alma Davenport, The History of Photography: An Overview (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1999)

Bengal Civilian, The Singapore Chapter of Zieke Reiziger, or, Rambles in Java and the Straits in 1852 (Singapore: Antiques of the Orient, 1984). (Call no. RSING 959.57 BEN)

Charles Burton Buckley, An Anecdotal History of Old Times in Singapore, 1819–1867 (Singapore: Oxford University Press, 1984). (Call no. RSING 959.57 BUC-[HIS])

From the Family Album: Portraits From the Lee Brothers Studio, Singapore 1910–1925 (Singapore: Landmark Books for National Heritage Board, 1995). (Call no. RSING 779.26095957 FRO)

Gordon Baldwin, Looking at Photographs: A Guide to Technical Terms (California: J. Paul Getty Museum in association with British Museum Press, 1991). (Call no. RART 770.3 BAL)

Gretchen Liu, Singapore: A Pictorial History, 1819–2000 (Singapore: Archipelago Press in association with the National Heritage Board, 1999). (Call no. RSING 959.57 LIU-[HIS])

John Falconer, A Vision of the Past: A History of Early Photography in Singapore and Malaya: The Photographs of G.R. Lambert & Co. (Singapore: Times Editions, 1987). (Call no. RSING 779.995957 FAL)

John Thomson, The Straits of Malacca, Indo-China and China: Travels and Adventures of a Nineteenth-Century Photographer (Singapore: Oxford University Press, 1993). (Call no. RSING 915.9 THO)

Liz Wells, ed., Photography: A Critical Introduction (London: Routledge, 2004). (Call no. RART 770.1 PHO)

Munshi Abdullah, The Hikayat Abdullah, trans. A. H. Hill (Singapore: Malaya Publishing House, 1955). (Call no. RCLOS 959.5 ABD)

Naomi Rosenblum, A World History of Photography (New York: Abbeville Press Publishers, 1997). (Call no. RART 770.9 ROS)

National Museum (Singapore), National Museum of Singapore: Topping Off Ceremony, Monday, 28 November 2005, 7.00 PM (Singapore: National Museum of Singapore, 2005). (Call no. RSING 708.95957 NAT)

Robert Hirsch, Seizing the Light: A History of Photography (Boston: McGraw-Hill, 2000). (Call no. RART 770.9 HIR)

NOTES

-

Liz Wells, ed., Photography: A Critical Introduction (London: Routledge, 2004), 46–47. (Call no. RART 770.1 PHO) ↩

-

John Falconer, A Vision of the Past: A History of Early Photography in Singapore and Malaya: The Photographs of G.R. Lambert & Co. (Singapore: Times Editions, 1987), 187. (Call no. RSING 779.995957 FAL) ↩

-

National Museum (Singapore), National Museum of Singapore: Topping Off Ceremony, Monday, 28 November 2005, 7.00 PM (Singapore: National Museum of Singapore, 2005), 15–16 (Call no. RSING 708.95957 NAT); Gretchen Liu, Singapore: A Pictorial History, 1819–2000 (Singapore: Archipelago Press in association with the National Heritage Board, 1999), 36. (Call no. RSING 959.57 LIU-[HIS]) ↩

-

Bengal Civilian, The Singapore Chapter of Zieke Reiziger, or, Rambles in Java and the Straits in 1852 (Singapore: Antiques of the Orient, 1984), 1. (Call no. RSING 959.57 BEN) ↩

-

Charles Burton Buckley, An Anecdotal History of Old Times in Singapore, 1819–1867 (Singapore: Oxford University Press, 1984), 341. (Call no. RSING 959.57 BUC-[HIS]) ↩

-

“Page 1 Advertisements Column 2: Gaston Dutronquoy,” Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, 11 April 1839, 1. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Buckley, An Anecdotal History of Old Times, 341. ↩

-

Robert Hirsch, Seizing the Light: A History of Photography (Boston: McGraw-Hill, 2000), 33. (Call no. RART 770.9 HIR) ↩

-

Naomi Rosenblum, A World History of Photography (New York: Abbeville Press Publishers, 1997), 43–44. (Call no. RART 770.9 ROS) ↩

-

Hirsch, Seizing the Light, 33. ↩

-

Munshi Abdullah, The Hikayat Abdullah, trans. A. H. Hill (Singapore: Malaya Publishing House, 1955), 257. (Call no. RCLOS 959.5 ABD) ↩

-

Falconer, Vision of the Past, 13. ↩

-

Falconer, Vision of the Past, 5–6; Alma Davenport, The History of Photography: An Overview (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1999); Gordon Baldwin, Looking at Photographs: A Guide to Technical Terms (California: J. Paul Getty Museum in association with British Museum Press, 1991), 15. (Call no. RART 770.3 BAL) ↩

-

John Thomson, The Straits of Malacca, Indo-China and China: Travels and Adventures of a Nineteenth-Century Photographer (Singapore: Oxford University Press, 1993), xix–xx. (Call no. RSING 915.9 THO) ↩

-

Thomson, Straits of Malacca, Indo-China and China, xxiii. ↩

-

From the Family Album: Portraits From the Lee Brothers Studio, Singapore 1910–1925 (Singapore: Landmark Books for National Heritage Board, 1995), 11. (Call no. RSING 779.26095957 FRO) ↩