Money Lending: A Short History

Singapore is today a well-developed financial centre with many banks and other financial institutions offering a suite of banking products and services. But it was a completely different scene during the colonial era.

Singapore’s First Banks

In the early 19th century, when Stamford Raffles first set foot on Singapore, it was essentially a small fishing village whose residents relied mainly on barter trade for goods and services. Soon after Raffles established Singapore as an entrepot port, trading activities expanded rapidly, and there naturally arose a need for banking facilities to support the growing number of traders and merchants on the island.

It was first suggested that a bank be established in Singapore in 1833. However, it was not until 1840 that a branch of the Union Bank of Calcutta was opened here. The bank offered merchants advances on goods to be imported, up to three-fourths of their value at an interest rate of 9 percent. It also provided loans against bullion, up to 90 per cent of its value, with an interest rate of 7 percent. Other banks subsequently opened branches in Singapore - the Oriental Bank in 1846, the Mercantile Bank of India in 1855, Nederlandsche Handel MaatscNapy in 1857, Chartered Bank in 1859, and the Hong Kong and Shanghai Bank in 1866.

In the beginning, these banks were established primarily for the China trade. Their business was confined to providing trade financing and currency exchange services for traders and merchants plying their trade in the region, and their main clientele was the European mercantile community.

When it came to dealing with Chinese traders and merchants, each bank found it expedient to hire a local middleman known as the comprador (Portuguese for “buyer”). The banks lent money to Chinese merchants and traders through the comprador, who was responsible for every Chinese account opened. The comprador was also responsible for hiring and managing all local staff. In the early days, compradors were men with good connections and established family backgrounds.

Until the beginning of the 20th century the banking system in Singapore consisted mainly of European Banks. It was only at the turn of the 20th century that the first Iocal banks were established. Kwong Yik Bank was the first Chinese bank: It was set up in 1903 by Wong Ah Fook and several Cantonese businessmen. The bank’s services included banking facilities, mortgages and loans, and its clientele was mainly Chinese. The second Chinese bank, Sze Hai Tong, was set up in February 1906. One of its directors, Tan Swi Phiau, also held the important position of comprador to Netherlands India Commercial Bank.

The Rise of Agency Houses

Another source of finance for many businesses were agency houses such as Guthrie & Co. Established in the 19th century by colonial pioneers, these companies had started off as trading businesses, but later diversified into non-trading businesses such as banking and finance.

Guthrie & Co., for instance, started off as an import-export establishment. As the company accrued assets from the profits it made from trading activities, it decided to make good use of the surplus assets by providing finances for other people’s business ventures, such as building factories and sawmills in Singapore. It also provided loans to businesses such as tin-mining and rubber cultivation in the Malay states.

Enter The Chettiars

Outside the realm of European banks and agency houses, the chettiars were the most prominent professional moneylenders. They were an influential class of merchants from South India who had over time established a reputation in the field of commerce and finance. As the Europeans expanded their colonial influence in Southeast Asia in the 19th century, the chettiars had also extended their network throughout the region.

By the end of the 19th century, the chettiars had become a formidable force in the business of moneylending in Singapore, having large amounts of capital at their command. Many chettiars were agents of wealthy men in India who were the main source of capital. They also made use of capital from local depositors and European banks, obtaining money from the basis on demand notes signed by two or more chettiars. The amounts advanced by the banks on the demand notes depended on the standing of the chettiars who signed them.

In some cases, banks would insist on a personal guarantee from the chettiars own “shroff,” or head cashier, as an additional precaution. Nevertheless, so great was the business aptitude and reputation of the chettiars, that the losses incurred by the banks in dealing with them were relatively small (Wright, 1908, p. 141). The money obtained from banks was then lent out to others, such as Chinese traders, at higher rates of interest.

The chettiar’s loans operated in the following manner: The borrower would be required to sign a promissory note, and this was considered sufficient for small loans and loans granted without collateral. For larger amounts, jewels, gold or land title deeds were held as collateral.

The amount actually received by the borrower would be less than that stated on the promissory note. A rate of interest would be charged on the amount mentioned in the promissory. If the borrower did not repay the principal and interest on the due date, the amount owed would be automatically adjusted to comprise the principal and accrued interest, and a higher interest would be charged.

By lending to the chettiars, the European banks were able to profit from the local credit market with a much reduced risk. At the same time, local borrowers got access to capital from the European banks, which would otherwise have been unavailable. Most of the Chinese traders and merchants were illiterate, and hence turned to chettiars instead of banks, as it involved fewer formalities, less hassle and minimal documentation.

By the late 19th century, the chettiars were among the wealthiest members of the community. However, most of them led a simple lifestyle, as illustrated in the following description of chettiars in early 20th century Singapore.

“They were amongst the wealthiest members of the community, but they live in a very simply way. Their dress consists merely a strip of muslin cloth wound loosely round their limbs and a pair of leather sandals. As an ornament they often wear a gold wire round the neck with a massive gold ornament attached to it. They seldom or never purchase any of the luxuries of Western civilisation, but they spend large sums of money on the Hindu Temple which they attend.” (Wright, 1908, p. 141)

However, chettiars were at times criticised for usury and labelled as “Shylocks of the East” (Wright, 1908, p. 219). This was not helped by the fact that chettiars were not slow to bring people to court to enforce loan agreements. Indeed, it was a common saying that chettiars spent their time between the banks and the court.

Arab, Chinese and Sikh Moneylenders

Apart from the chettiars, there were also Arab, Chinese and Sikh moneylenders. Chinese moneylenders ranged from wealthy businessmen to itinerant moneylenders such as shopkeepers, who provided small credit. These moneylenders often provided a source of capital for Chinese immigrants to set up small businesses, though not all business did well:

“After completing their twelve months as Sinkehs, many get an advance of money from town shopkeepers, clear a piece of forest, land, plant vegetables, plaintains and indigo at first, and eventually gambier and pepper; under certain government regulations forest lands are thus cleared and cultivated, and a grant obtained in perpetuity from the state. The returns are so slow, and the exactions of the money lenders so stringent, that in a few years the squatters are forced to sell their land to repay their creditors. Hokkiens are often the purchasers.” (Vaughn, 1879, p. 15)

The Sikhs were first recruited from Punjab to go to Malaya to serve as policemen. As the Sikh community in Singapore expanded, a number of them went into the business of moneylending, which was not a difficult trade to learn and offered good profits.

Unlike Chinese and Sikh moneylenders, Arab moneylenders had to avoid Islamic prohibitions on interest dealings, and relied on other means, such as making use of real estate, for their moneylending activities.

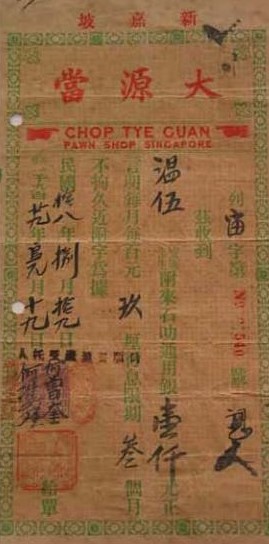

The First Pawnshops

For the majority of the population, the most easily available lending facility in times of need was the pawnshop. The pawnbroking business, which had a long history in China, was brought to Singapore by Chinese immigrants. As the only banks available in the early days were European and most of the Chinese immigrants spoke no English, they naturally fell back on the traditional practice of pawnbroking.

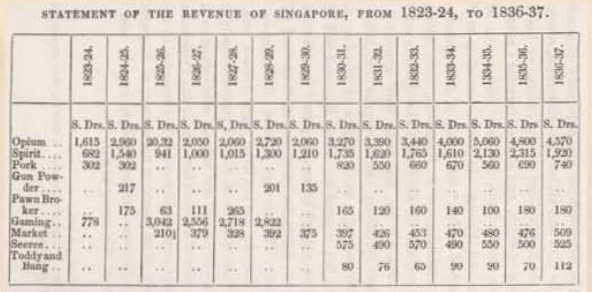

Since the early 19th century, pawnbroking activities had been widespread in Singapore. They served as a source of revenue for the British colonial administration, which had adopted the practice of revenue farming. This gave those holding the contracts of revenue farms the sole right to sell opium and spirits, and to manage gambling and pawnbroking businesses.

However, in 1830, instead of issuing licences to individual pawnbrokers, the colonial administration decided to revert to the farming system by giving the pawnbroker farmer the exclusive right to run the pawnbroking business. Describing the pawnbroking scene in Singapore, John Cameron, an editor of the The Straits Times in the 1860s, wrote that “in Singapore alone, where there are not 100,000 souls, the farmer can pay a premium of 450/ a month for a monopoly of the pawnshops.” (Cameron, 1865, p. 218)

The farming system offered a few advantages for the colonial administration. Firstly, by giving the pawnbroker farmer the exclusive right to operate the pawnbroking business, it was able to avoid having to manage pawnbroking activities and collecting dues from pawnbrokers.

Secondly, the farming system tended to bring about higher revenue, since interested pawnbrokers bidded highly to secure the pawnbroking farms. However, this raised concerns that the system tended to result in high interest rates, because pawnbrokers naturally charged more to meet the high rents. The issuing of licenses was seen as a better solution to keep interest rates low.

This was perpetual dilemma for the colonial administration, and in the ensuing decades, it oscillated between revenue farming and regulation by licensing. This continued until 1934, when the colonial government implemented a new system, in which pawnbrokers’ licenses were granted in a tender system.

The first pawnshop in Singapore was Sheng He Dang, set up by Lan Quishan and a few partners. In 1878, He Yuan Shi obtained the first pawnbroking farm from the Straits Settlements government. He operated eight pawnshops and paid an annual fee of $200 for each. In the early days, the pawnbroking business was dominated by Hokkiens and Teochews, two of the largest dialect groups among the Chinese immigrants. However, they were later superseded by the Hakkas. By 1941, there were 26 pawnshops, 24 of which were owned by Hakkas.

At the beginning of the 20th century, many of the pawnbrokers also went into banking business. For instances, when Kwong Yik Bank was first established in 1903, five of the bank’s 11 directors were proprietors of pawnshops, including the managing director, Lam Wei Fong.

Pawnshops remained an important source of lending for the community at large until recent years. Unlike the affluent class, most people did not own land nor other recognised assets against which they could borrow from the banks. While they charged higher interest than any other forms of commercial credit, pawnshops enabled people without large assets to borrow money for weddings, funerals or festivals.

HUI

The hui was another popular source of lending among local Chinese. In Western terms, the hui was commonly referred to as “tontine”, an annuity scheme named after Neapolitan banker Lorenzo Tonti, who started the scheme in France around 1653.

Like the tontine, the hui was a form of loan association set up for mutual assistance. Each member would pay a fixed amount to hui every month, and each month, a different member had the use of the total amount collected. Those who wanted to use the money that month would bid for the privilege, with the member offering the highest interest, securing the loan.

The membership size of a hui ranged from 10 to 60. Members met for the monthly “drawing”, which was usually held at the beginning of the month at the organiser’s residence. At the meeting, members tendered for the loan by passing slips of paper to the organiser stating the rate of interest they offered. The cash was then collected and handed over to the highest bidder.

The organiser often got a fee called teh poh for bringing the participants together. In the early years, account books were rarely kept, as the organisers or managers were often illiterate. They kept record of members’ obligations and liabilities by “numerals, dots, circles and crosses (tulisan ayam)” (Koh, 1938, p. xi). Subsequently, it became a common practice to issue members with account books called Wui Poh, on which organisers would acknowledge the contributions received from members.

However, the hui had its risks - advances were given without collateral, and participants were susceptible to risks such as the death or default of memebrs, or the failure of the headsman to pay up the subscription collected. Moreover, participants were not protected by law, even though written accounts could be presented by the organiser to the subscribers; the Societies Ordinance made by any loan association with 20 or more members unlawful if unregistered.

Despite the risks, the hui was a popular source of lending for local Chinese who had little access to banks or could not offer collateral. The common folk relied on its as as source of lending to meet emergency or short-term needs, such as hospital bills or children’s weddings, and small Chineses traders relied on it for their credit needs.

For those with surplus assets, the hui acted like a “savings bank” that offered a higher rate of interest then banks. The hui was reportedly very popular among the women folk, who saw it as a means to invest and increase their savings. It was said that “nine out of every 10 amahs and three out of every 10 nonyas” were members of a hui. (Koh, 1938, p. xll)

Among the local Indians, there was a loan association similar to the hui called kutoo or Kuthu. However, there was no interest and members’ right to borrow was determined by casting lots. For Indian immigrants, the kutoo provided a means of securing capital to set up a small business, such as selling iced water or a cigarette stall in a corner shop.

Reference Librarian

Lee Kong Chian Reference Library

National Library

REFERENCES

Arnold Wright and H.A. Cartwright, eds., Twentieth Century Impressions of British Malaya: Its History, People, Commerce, Industries, and Resources ([London]: [Lloyd’s Greater Britain Publishing Company, Limited], 1908). (Call no. RRARE 959.5103 TWE)

C. Gamba, “Poverty, and Some Socio-Economic Aspects of Hoarding, Saving and Borrowing in Malaya,” Malayan Economic Review 3, no. 2 (October 1958): 33–62. (Call no. RCLOS 330.9595 MER)

Douglas Wong, HSBC: Its Malaysian Story (Kuala Lumpur: Editions Didier Millet, 2004). (Call no. RSING q332.1509595 WON)

Hans-Dieter Evers and Jayarani Pavadarayan, “Religious Fervour and Economic Success: The Chettiars of Singapore,” in Indian Communities in Southeast Asia, ed. K.S. Sandhu and A. Mani (Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, 2006). (Call no. RSING 305.891411059 IND)

He Qianxun 何谦训, Xinjiapo dian dang ye zong heng tan 新加坡典当业纵横谈 [Talking about the pawnbroker industry in Singapore] (Xinjiapo 新加坡: Xinjiapo Chayang (Dabu) hui guan, Xinjiapo dang shang gong hui 新加坡茶阳(大埔)会馆, 新加坡当商工会 2005). (Call no. Chinese RSING 332.34095957 HQX)

J. D. Vaughan, The Manners and Customs, of the Chinese of the Straits Settlements (Singapore: Printed at the Mission Press, 1879). (From BookSG; call no. RRARE 390.0951 VAU; microfilm NL2437)

John Cameron, Our Tropical Possessions in Malayan India: Being a Descriptive Account of Singapore, Penang, Province Wellesley, and Malacca; Their Peoples, Products, Commerce, and Government (London: Smith, Elder and Co, 1865). (From BookSG; call no. RRARE 959.5 CAM; microfilm NL11224)

Koh C. J., Hway, Chinese Loan Societies, Malayan Law Journal 7, xi–xdl. (microfilm NL3493)

Lal Harcharan Singh, Law of Moneylenders in Malaysia and Singapore (Malaysia: Sweet & Maxwell Asia, 2003). (Call no. RSING 346.5957073 SIN)

Rajeswary Ampalavanar Brown, Capital and Entrepreneurship in South-East Asia (Hampshire: The Macmillan Press Ltd., 1994). (Call no. RSING 338.040959 BRO)

S. K. Das, “Nattukottai Chettiars in Malaya,” Malayan Law Journal 24 (1958): xiv–xxii, xxvi–xxiii. (Call no. RCLOS 340.05 MLJ)

Sjovald Cunyngham-Brown, The Traders: A Story of Britain’s South-East Asian Commercial Adventure (London: Newman Neame, 1971). (Call no. RSING 382.0959 CUN)

T. J. Newbold, Political and Statistical Account of the British Settlements in the Straits of Malacca, Viz. Pinang, Malacca, and Singapore: With a History of the Malayan States on the Peninsula of Malacca, vol 1. (London: J, Murray, 1839). (From BookSG; call no. RRARE 959.5 NEW; microfilm NL5141)

Yasser Mattar, Ethnic Entrepreneurship: Towards an Ecological Perspective (Singapore: Dept. of Sociology, National University of Singapore, 2000). (Call no. RSING q338.04095957 MAT)