Storm in Shuang Lin

Shuang Lin Monastery was once used as a training ground for people who volunteered their services at the Burma Road, which served as a supply route during the Sino-Japanese War in the 1930s. The monastery had a great impact on the lives of two men: Wu Hui Min, volunteer for the war effort, and Venerable Pu Liang, the abbot of the monastery.

The Sino-Japanese War began on 7 July 1937. As the war developed, the Chinese seaports were either captured or blocked by the Japanese who attempted to terminate external supplies entering China. In response, the Chinese government developed alternative land supply routes.

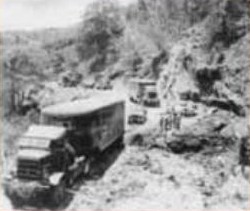

The Burma Road, built as an alternative supply road, became China’s most important supply route. The Singapore Free Press described it as China’s new munitions and supplies route.1

Construction of the Burma Road between Yunnan in China and Lashio in Burma began in 1937 and was completed in 1938. Supplies were sent by sea to the Rangoon port (Yangon), transported by rail to Lashio and through the Burma Road to Kunming in China. The journey from Kunming to Lashio took about a week, and there were six stations along the route to support the drivers.

Due to the lack of experienced drivers and mechanics in China, the Chinese government requested Mr Tan Kah Kee, the Chairman of the China Relief Fund, to recruit drivers mechanics from Nanyang (South East Asia).

The Nanyang Federation of Relief Fund was founded in 1938 to support China in the Sino-Japanese War. Mr Tan Kah Kee had been elected as its chairman, and its regional office was located at the Ee Hoe Hean Club in Singapore. Representatives of the Fund set up their local China Relief Fund offices to implement programmes, forming a large network around the region.

The China Relief Fund raised money to purchase medication, medical equipment, clothing, food and military hardware such as planes, tanks, trucks, explosives and weapons,2 transforming the Overseas Chinese population into a regional force in support of China.

Drivers and Mechanics from Nanyang

In response to the Chinese government’s request for volunteers from Nanyang, the China Relief Fund published the first recruitment notice (number 6) on 7 February 1939.3

Among the candidates who responded were applicants who had borrowed licences or had very limited driving skills. At the same time, information from China indicated that the roads required extremely good driving skills. So the China Relief Fund decided to test drivers and to establish a Driving Institute.

After background checks were conducted, candidates whose driving licences had a photo were accepted while others were tested near Outram Road. Initially, the test involved basic driving skills with an empty truck. When further information on road conditions came in, the testers for the third or fourth and subsequent batches attempted to simulate road conditions in China by testing candidates on more difficult terrain on Neo Tiew Road, and the trucks were loaded to increase driving difficulty.

These who could not drive were sent to the Driving Institute located in Shuang Lin Monastery. The coordinators included Mr Ng Aik Huan, Mr Lau Boh Tan and a training committee formed by a group of skilled drivers.

The Shuang Lin Monastery was founded in 189B by Mr Low Kim Pong when he invited Venerable Xian Hui to be The first Abbot. It was the first Buddhist monastery in Singapore and one of the largest in the region.

Mr Ng recalled training and testing the candidates at the Shuang Lin Monastery, and described the training location as a “very big place” that was acquired by the government amid the post-war housing development projects. Dr Low Cheng Jin, grandson of Mr Low Kim Pong, mentioned that the training was conducted “behind the temple” where “entry could be made by the other side, not necessary through the temple’s gate”. At the back of the temple was a piece of open land with access roads.

On 7 July 1939, Mr Tan Kah Kee issued a notice4 for more volunteers and cited recruitment efforts in Singapore, mentioning the recruitment of 200 semi-skilled drivers who were trained at a “distant location with rough terrain “ for about three weeks. He then recommended other China Relief Fund local offices to adopt similar strategies to produce more qualified volunteers. The “distant location with rough terrain” was probably the land behind the monastery.

On To The Burma Road

Qualified volunteers from Nanyang converged in Singapore to form a batch Between February and August 1939, about 3,2005 volunteers left in nine batches. The majority were Chinese men, but there were also Indians. Malays and four Chinese women.6 These volunteers were known as Drivers and Mechanics from Nanyang. About 1,000 of them died in service, 1,000 settled in China and others returned to Nanyang after the war.

China’s wartime leader Chiang Kai Shek said that the volunteers “spontaneous offer of service to the country in the hour of crisis has not only brought material aid to China in the war of independence, but has also demonstrated to the world that the Chinese people everywhere are united by common loyalty”.7

One of the volunteers who were trained in the Driving institute was Mr Wu Hui Min.

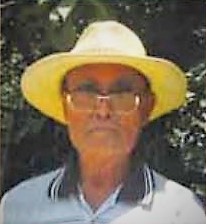

My Wu Hui Min 8

Mr wu Hui Min was born in Hainan, China, and came to Singapore in 1934 when he was 15 years old. In Singapore, he worked for the Wu association and had the opportunity to read the Chinese newspapers every day. They updated him with developments of the Sino-Japanese war, and he participated in fund-raising activities like selling flowers, attended rallies and boycotted Japanese goods.

In 1939, Hainan Island fell to the Japanese and Mr Wu felt a deep sense of loss. He wanted to contribute towards the war efforts, as he felt that he did not have a home to return to, and believed that everyone should do whatever he could in a time of crisis.

For volunteers like Mr Wu, the Japanese Occupation of their homes had initiated a process in which they transformed the despair of personal loss into efforts towards the protection of their larger cultural homeland.

During this time, Mr Wu came across the notice for volunteers for the Burma Road, and went to register at the Shuang Lin Monastery.9 All the volunteers lived in the Driving Institute and were trained by instructors. They started the day with morning exercises and military training, after which they had driving lessons. A few trainees shared a truck and took turns to drive.

(Right) Mr Wu Hui Min and his batch of volunteers gathered at the Tong Ji Hospital before they left Singapore. Earlier batches of volunteers had stayed in the hospital.

After three weeks of training, Mr Wu joined 506 others to form the ninth batch. They stayed at the Great Southern Hotel and left Singapore on 14 August 1939. At 6am, they gathered at Tongji Hospital and left for Tanjong Pagar harbour at 10am. The harbour was by then already crowded with people who had come to send them off. As the vessel Feng Qing left the harbour at 3pm, the crowds sang to encourage the volunteers and to bid them farewell.10

The Sook Ching Massacre

On 7 February 1942, Japan began the invasion of Singapore. By 15 February, the British had surrendered and Singapore became Syonan. On 21 February, the Japanese launched “Sook Ching” to “clean up all anti-Japanese elements.”11

All male Chinese between the ages of 18 and 50 had to assemble at five assembly points at noon. One of them was Jalan Besar, where anti-Japanese suspects were transported to Changi Beach “just outside the wire of the Changi Prisoner of War camp”12 for execution.

One of the victims of Sook Ching was Venerable Pu Liang, Abbot of Shuang Lin Monastery, who had allowed the China Relief Fund to establish the Driving Institution inside the monastery.

Venerable Pu Liang 13

Venerable Pu Liang came to Singapore in 1912. In 1917, he became the 10th Abbot of Shuang Lin Monastery. From 1937 till his execution, the Venerable served as the chairman of the Chinese Buddhist Association, a Buddhist charity and social association.

Venerable Pu Liang had two disciples to assist him in temple management, serving as an accountant and a clerk. Both assistants were “very devoted”14 to the Venerable.

The Venerable was a highly regarded and well-respected person who enjoyed wide support across different sectors of the Chinese community. During the Sino-Japanese war, he was involved in various activities to support the China Relief Fund and help war victims. A Chinese newspaper described him as “very active in relief work”.[^15]

On Vesak Day in 1939, he worked with the China Relief Fund to launch the “Shuang Lin Monastery Vesak Day Vegetarian Meal Fund Raising Event”. Held on 28 May15 in the monastery, it attracted “a few thousand” participants and raised about $10,000 (Straits Dollars). It was covered by major newspapers.16

In early 1942, during Sook Ching, a group of Japanese soldiers arrived at the Shuang Lin Monastery to arrest Venerable Pu Liang. They had to force their way in, and upon entering, arrested the Venerable and his two disciples immediately. The rest of the people were ordered to squat along the corridors. The soldiers proceeded to search the Venerable s rooms, and opened trucks and lockers. Dr Low Cheng Jin, who was present, believed that the Japanese were looking for evidence of Venerable Pu Liang’s “ anti-Japanese” activities. Mr Ng Aik Huan, the China Relief Fund leader, believed that the Japanese found some belongings and marketing materials belonging to the Driving Institute’s volunteers.17

Venerable Pu Liang, his two disciples and others in the monastery were taken to the Jalan Besar inspection point. Most of the people who reported to Jalan Besar were released about a week later, but the three Venerables did not return. The monastery sent people to search for them, but they could not find them. They and Mr Ng concluded that the Japanese had executed the Venerables.

A Targeted Arrest

Although Venerable Pu Liang had participated actively in support of relief work for the war, many other Buddhist and Taoist organisations had held similar events. For example, in July 1939, a seven-day Chinese opera was put up at Tian Fu Gong to raise funds for the China Relief Fund.18

The Chinese Chamber of Commerce - whose chairman was Mr Tan Kah Kee, Japan’s most wanted man - managed Tian Fu Gong. Yet, during the Japanese occupation, temples19 managed by the Chinese Chamber of Commerce were not disturbed.20 Venerables from major Buddhist institutions21 that participated in memorial services and China Relief Fund activities were also left unharmed.

For example, Venerable Rui Yu Abbot of Seng Hong Temple had donated money22 and participated in China Relief Fund programmes. After Venerable Pu Liang’s execution, he became the Chairman of the Chinese Buddhist Association and sought permission from the Japanese authorities to resume the association’s activities.23

In general, Japanese troops were advised not to disturb religious institutions.24 Therefore, the Japanese soldiers who went to Shuang Lin Monastery probably knew whom they wanted and what “crimes” they had committed.

The Burma Road was seen as China’s major lifeline, and the Japanese had attempted to terminate it through diplomatic and military means. The fall of Singapore was perceived as a means for the Burma Road “to be completely cut off in the near future”.25

Even though Venerable Pu Liang had offered only the physical place, the Driving Institute was seen as part of the larger network to supply volunteers to the Burma Road. Shuang Lin Monastery was reported in the press as a recruitment and training ground for volunteers to the Burma Road, and training was conducted in the open, visible to people around the monastery, so it was not difficult for the Japanese to know about its activities. From the Japanese perspective, “volunteers” meant “guerillas”.26

This may have explained why the Venerable’s rooms and the monastery were searched. Usually, Japanese soldiers would arrive to inform residents about inspections, but would not search the place.

Like most of the victims from Jalan Besar Inspection Point, Venerable Pu Liang and his two disciples were likely executed at Changi beach. The Venerable was probably the only Chinese Buddhist religious leader executed,27 and he and his two disciples probably the only Chinese Venerables executed during Sook Ching.

A Pow Witness

A British prisoner-of-war may have witnessed the execution of Venerable Pu Liang. Mr John Hamilton Wadge,28 a Corporal (Service number 993369), was part of the Royal Army Service Corps attached to the 53rd Infantry Brigade of the 18th Division. Following the fall of Malaya, the 18th Division retreated to Singapore and was assigned to protect the northern shores of Singapore. On the day of surrender on 15 February 1942, the 53rd Brigade was stationed along Braddell Road.

Mr Wadge’s group had moved southwards along Thomson road and taken shelter in an abandoned house, the former residence of a Michelin employee who had been evacuated from Singapore. They had been taken as prisoners of war in this house and transferred to the Changi area.

Mr Wadge witnessed three Chinese monks in robes being executed at the beach.

History Remembered

The volunteers to the Burma Road and their supporters were people from all walks of lives. Their decisions and actions were propelled by a cuturally-conditioned world view, and through their actions, these individuals became the embodiments of global-local forces. Their stories enable us to understand how an event influenced and impacted individuals, and how their actions shaped the course of the Sino-Japanese War.

As the place where volunteers were trained and whose Abbot paid a heavy price during Sook Ching, Shuang Lin Monastery is one of the few institutions29 related to Burma Road volunteers that still exist, making it a “living” institution and a depository for the nation’s collective social memories. The monastery was gazetted as a National Monument on 17 October 1980, and has embarked on a restoration project that continues to this day.

This is an extract from a paper, Storm in Shuang Lin: Ethnography of Social Actors in the Political Climate of 1939–1942, by Mr Chan Chow Wah, a Fellow of the Royal Anthropological Institute and Member of the American Anthropological Association. He presented this paper in December 2006 as part of the inaugural Lee Kong Chian Research Fellowship Series.

Lee Kong Chian Research Fellow

REFERENCES

Alan Houghton Brodrick,** Beyond the Burma Road (London: Hutchinson, 1945). (Call no. RUR 940.5425 BRO)

Brian P. Farrell, The Defence and Fall of Singapore 1941–42 (Stroud: Tempus, 2005). (Call no. RSING 940.5425 FAR)

C.F. Yong, Chinese Leadership and Power in Colonial Singapore (Singapore: Times Academic Press, 1992). (Call no. RSING 959.5702 YON)

C.M. Turnbull, A History of Singapore, 1819–1988 (Singapore: Oxford University Press, 1989). (Call no. RSING 959.57 TUR)

Daniel Chew and Irene Lim, eds., Sook Ching (Singapore: Oral History Department, 1992. (Call no. RSING 959.57023 SOO)

Gretchen Liu, In Granite and Chunam: The National Monuments of Singapore (Singapore: Landmark Books and Preservation of Monuments Board, 1996). (Call no. RSING 725.94095957 LIU)

Gretchen Liu, Singapore: A Pictorial History, 1819–2000 (Singapore: Archipelago Press in association with the National Heritage Board, 1999). (Call no. RSING 959.57 LIU)

History of the Chinese Clan Associations in Singapore (Singapore: Singapore News & Publications Ltd, 1986). (Call no. RSING q959.57 HIS)

Ian Ward, The Killer They Called a God (Singapore: Media Masters, 1992). (Call no. RSING 959.57023 WAR)

J.A.G. Roberts, The Complete History of China (Gloucestershire: Sutton Pub., 2003). (Call no. R 951 ROB)

Jon Latimer, Burma: The Forgotten War (London: John Murray, 2004). (Call no. RSEA 940.5425 LAT)

Lee Geok Boi, Syonan: Singapore Under the Japanese 1942–1945 (Singapore: Singapore Heritage Society, 1992). (Call no. RCLOS 959.57 LEE)

Lee Lai To, ed., Early Chinese Immigrant Societies: Case Studies From North America and British Southeast Asia (Singapore: Heinemann Asia, 1988). (Call no. RSING 305.8951059 EAR)

Lee Poh Ping, Chinese Society in Nineteenth Century Singapore (New York: Oxford University Press, 1978). (Call no. RSING 301.45195105957 LEE)

Lee Poh Ping, Chinese Society in Nineteenth and Early Twentieth Century Singapore: A Socioeconomic Analysis ([Ithaca, N.Y.]: Cornell University, 1974). (Call no. RCLOS 301.45195105957 LEE)

Leslie Anders, The Ledo Road; General Joseph W. Stilwell’s Highway to China (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, [1965]). (Call no. RUR 940.5425 AND)

Louis Allen, Singapore, 1941–1942 (London: Frank Cass, 1993). (Call no. RSING 940.5425 ALL)

Low Cheng Gin, oral history interview by Yeo Geok Lee, 3 June 1983–12 August 1983, transcript, MP 3 audio, Reel/Disc 1 to 23, National Archives of Singapore (accession no. 000287)

Low N. I., When Singapore Was Syonan-To (Singapore: Times Books International, 1995). (Call no. RSING 959.57023 LOW)

Mamoru Shinozaki, Syonan, My Story: The Japanese Occupation of Singapore (Singapore: Asia Pacific Press, 1975). (Call no. RCLOS 940.548252 SHI)

Masanobu Tsuji, Singapore 1941–1942: The Japanese Version of the Malayan Campaign of World War, trans. Margaret E. Lake (Oxford University Press, 1988). (Call no. RSING 940.5425 TSU-[WAR])

Ng Aik Huan, oral history interview by Tan Ban Huat/Tan Beng Luan, 3 April 1981–10 July 1984, transcript, MP3 audio, Reel/Disc 1 to 15, National Archives of Singapore (accession no. 000035)

Pek Cheng Chuan, oral history interview by Lim How Seng, 23 July 1980, transcript, MP3 audio, Reel/Disc 1 to 8, National Archives of Singapore (accession no. 000027)

Peter Duus, Ramon H. Myers, and Mark R. Peattie, eds., The Japanese Wartime Empire, 1931–1945 (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1996). (Call no. RSING 950.41 JAP)

Peter Elphick, Singapore: The Pregnable Fortress: A Study in Deception, Discord and Desertion (London: Hodder & Stoughton, 1995). (Call no. RCLOS 940.5425 ELP)

Peter Thompson, The Battle for Singapore: The True Story of the Greatest Catastrophe of World War II (London: Portrait/Piatkus, 2005). (Call no. 940.5425 THO)**

Richard Gough, SOE Singapore: 1941–42 (Singapore: Raffles, 2000). (Call no. RSING 940.5425 GOU)**

S. Woodburn Kirby et al., The War Against Japan (India: Natraj, 1989). (Call no. RUR 940.542 KIR)

See Hong Peng, oral history interview by Chua Ser Koon, 21 November 1981–3 February 1982, transcript, MP3 audio, Reel/Disc 1 to 31, National Archives of Singapore (accession no. 000135)

Shu Yun-Tsiao and Chua Ser-Koon, eds., Malayan Chinese Resistance to Japan 1937–1945: Selected Source Materials Based on Colonel Chuang Hui-Tsuan’s Collection (Singapore: Cultural & Historical Pub. House, 1984). (From PublicationSG)

Tan Pei-Ying, The Building of the Burma Road (London: Whittlesey House, McGraw-Hill Book Co., Inc., [1945]). (Call no. RUR 940.5472591 TAN)

Tay Yen Hoon, oral history interview by Chua Ser Koon, 17 June 1984–27 July 1983, transcript, MP3 audio, Reel/Disc 1 to 17, National Archives of Singapore (accession no. 000281)

The Singapore Press

The Syonan Times

Xu Yunqiao and Cai Shijun 许云樵 and 蔡史君, Xin Ma Hua ren kang Ri shi liao 1937–1945** 新马华人抗日史料 1937–1945 [Malayan Chinese resistance to Japan 1937–1945] (Xinjiapo 新加坡: Wen shi chu ban gong si 文史出版公司, 1984). (Call no. Chinese RSING 959.57023 MAL)

(Chinese references – cannot be copied)

NOTES

-

More Than 1,000 Malayan Volunteers in China,” Singapore Free Press, 1 June 1939, 14. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

In Chinese ↩

-

In Chinese, 8 February 1939, 9. ↩

-

In Chinese, 9 February 1939, 7. ↩

-

(In Chinese), 6 July 1939, 9. ↩

-

In Chinese ↩

-

The Singapore Free Press, 31 May 1939, 2. ↩

-

Wu Hu Min, personal communication, 16 July 2005. ↩

-

In Chinese, 22 August 1999, 11. ↩

-

In Chinese. ↩

-

Mamoru Shinozaki, Syonan, My Story: The Japanese Occupation of Singapore (Singapore: Asia Pacific Press, 1975), 21. (Call no. RCLOS 940.548252 SHI) ↩

-

Peter Thompson, The Battle for Singapore: The True Story of the Greatest Catastrophe of World War II (London: Portrait/Piatkus, 2005), 375. (Call no. 940.5425 THO) ↩

-

Information on Venerable Pu Liang is constructed through Shuang Lin monastery publication, oral history records, Chinese newspapers of the period and accounts of British POW and The Singapore Chinese Buddhist Association archives (In Chinese) ↩

-

Low Cheng Gin, oral history interview by Yeo Geok Lee, 3 June 1983–12 August 1983, transcript, MP 3 audio, Reel/Disc 1 to 23, National Archives of Singapore (accession no. 000287) ↩

-

(In Chinese), 29 May 1939, 7. ↩

-

(In Chinese), 29 May 1939, 9; (In Chinese), 29 May 1939, 9; (In Chinese), 29 May 1939, 9. ↩

-

Ng Aik Huan, oral history interview by Tan Ban Huat/Tan Beng Luan, 3 April 1981–10 July 1984, transcript, MP3 audio, Reel/Disc 1 to 15, National Archives of Singapore (accession no. 000035) ↩

-

(In Chinese), 6 July 1939, 7. ↩

-

The temples included Tian Fu Gong (In Chinese); Heng Shan Ting, Jin Lan Miao. ↩

-

(In Chinese) ↩

-

The Buddhist monasteries that were active in China Relief Fund activities and frequently mentioned in the press include: (In Chinese) ↩

-

(In Chinese), 17 July 1939, 10. ↩

-

Singapore Chinese Buddhist Association (In Chinese) archives ↩

-

Masanobu Tsuji, Singapore 1941–1942: The Japanese Version of the Malayan Campaign of World War, trans. Margaret E. Lake (Oxford University Press, 1988), 306. (Call no. RSING 940.5425 TSU-[WAR]) ↩

-

The Shonan Times, 20 February 1943, frontpage ↩

-

Tsuji, Singapore 1941–1942, xi. ↩

-

A list of monasteries and their Abbots were constructed from newspaper reports of China Relief Fund programs that mentions Venerables. The list is checked against respective monasteries, publications, and archives to verify if they were executed during the Sook Ching period. ↩

-

Information supplied by Ms Janet Hamilton Jacobs, youngest child of Mr. John Hamilton Wadge, personal communication, February 2006. ↩

-

Other locations include Tong Ji Hospital (In Chinese), Ee Hoe Club (In Chinese), Great Southern Hotel (In Chinese) ↩