Conceiving Ethnic dialectal Church Communities: A Mission Growth Strategy from 1888–1935

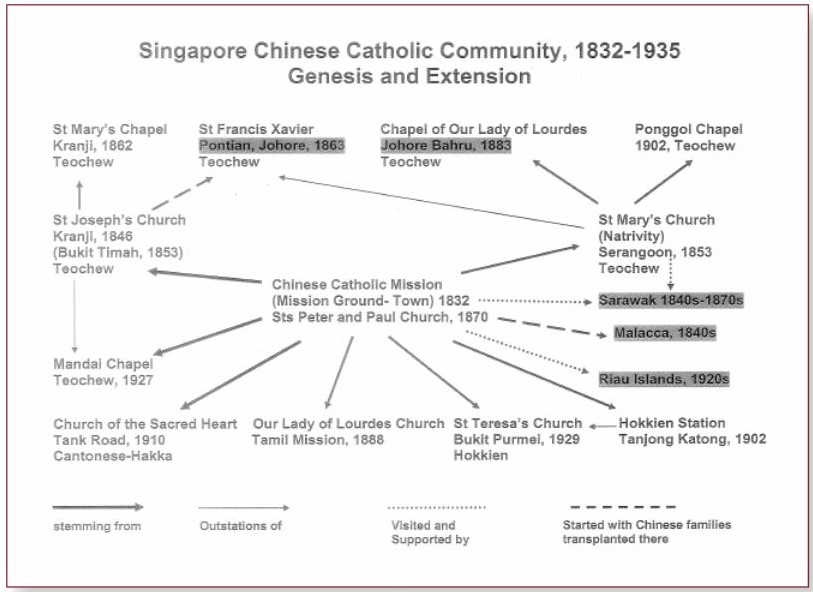

The French Roman Catholic Mission in Singapore found that church growth along ethnic lines was an effective strategy for indigenising and Asianising the local Catholic community in the pre-war years. Towards the turn of the century, the various dialectal communities within the Chinese Catholic Mission became sufficiently large enough to form separate parishes of their own.

Conceiving Ethnic-dialectal Communities

To foster an indigenised Chinese Catholic community, the missionaries had to foster amongst the Chinese Christians, a notion that as a whole, they constituted a distinct community, and as a community, they had a sufficient stake in Singapore to choose settlement over continual migration. To achieve this, the Church had to organise its various communities along the lines of language and ethnicity, and give them a place of their own to congregate and erect their communal social institutions. Hence, towards the turn of the century, while there was only one Chinese Catholic community, the need to further develop and root the Chinese Catholic community necessitated the Mission to form enclaves along dialectal lines. Although the pioneering Chinese parishes at Bukit Timah, Serangoon and in town were partly constituted by Chinese Christians from various dialect groups, they were nevertheless designated Teochew parishes, as the main body of the Chinese Christians were Teochews.1

In Serangoon, the Teochew Catholic community enjoyed rapid growth from the 1880s. From just 328 parishioners in 1883, this isolated Catholic community had grown to 700 by 1903, and this excluded the 350 at the Johor Bahru mission station, which was considered as part of the Serangoon parish. By 1916, the parish numbered 1,200, and was overseeing three schools, two for boys and one for girls, with 70 boys and 40 girls respectively.2 One reason for the Serangoon church’s impressive growth was that its progress had followed closely the economic progress of the district. The islands that faced the Serangoon and Punggol coastline had formed a natural estuary that favoured the development of a fishing industry and coconut cultivation.3 By the 1890s, most of the Chinese Christians at Serangoon were either coconut planters or fishermen,4 and their economic situation was invariably tied to the presence of the Church there. By this time, the Church had more than 50 acres of land in the district of which a large part was rented to parishioners for homes and farms.5

The plantations reared chickens and ducks in the natural ponds that were found all over the district in order that the droppings from the poultry might be used as manure.6 Many hired labourers from these plantations were eventually converted to Catholicism. At the sea front, a thriving fishing industry had also developed by 1900. Many young Chinese men who had come together to fish, lived in groups of eight or nine, in huts raised above the water, which they called “Yu Liao”.7 By 1910, there were several dozens of such “Yu Liaos” all across the Serangoon-Punggol coastline, and many young men from these huts were also converted to Christianity.

In 1906, when 100 parishioners of this mission station migrated closer to the Punggol coastline, Fr Saleilles, the parish priest of the station, erected a two-level house near them, where the ground floor was used as a chapel as well as a school for the Chinese of the district. Over time, this little Teochew Catholic enclave converted a number of Chinese residing there.8 By the 1920s, a large and visible Teochew Catholic enclave had emerged at the end of Serangoon Road, and such was the success of this enclave that the Bishop called it a “Catholic oasis”.9 In 1921, as an indication of the importance of this parish, the Serangoon church’s presbytery was chosen as a temporary site when the Mission wanted a local minor seminary to prepare young candidates for priesthood before sending them off to the major seminary at Penang. A proper seminary, christened St Francis Xavier Minor Seminary was finally erected next to the church in 1925.10

In town, there existed only two parishes till the 1870s: the European and Eurasian Catholics were considered “parishioners” of the Church of the Good Shepherd (made Cathedral in 1888) while the Mission’s Asiatic Christians were all housed under one roof within the Chinese Mission Church of Sts Peter and Paul, making the development of a distinct communal identity for the Chinese Mission in town much more difficult. It was especially so for the Indian Christians who had been placed within the Chinese Mission since the 1860s. By the 1880s, as the number of Indian Christians had grown sufficiently large enough to have their own church, steps were taken to separate the Indian Catholic Mission from the Chinese. Though many of the Indian Christians were still sojourners at this time, an increasing number had begun to form families in Singapore.11

By the mid-1880s, when there were 400 Indian Catholics at Sts Peter and Paul, the want of a parish of their own was never more felt. They found it increasingly more difficult to share the same premises with the Chinese Catholics.12 Furthermore, following the death of Fr Paris in 1883, there was no missionary who knew both languages, and hence, the Chinese and Indian Christians were assigned separate missionaries. In 1885, the missionary of the Indian Mission, Fr Meneuvrier, found a piece of ground along Ophir Road to build the Indian Christians their first church. It was completed in early 1888 and dedicated to Our Lady of Lourdes.13

The departure of the Indian Christians from the Chinese Catholic Mission did not leave Sts Peter and Paul a homogeneous parish. There remained a Chinese Catholic community divided by a multiplicity of Chinese dialects. In 1883, the Church of Sts Peter and Paul had only 795 Chinese Christians in its fold, but by 1900, there were 2,200.14 As early as 1889, the Bishop noticed that there was a great proliferation of Chinese families among the various Chinese Catholic dialect groupings in the Straits.15 In fact, by the early 1900s, the Bishop became concerned that the fast growing Chinese Mission and its increasing diversity would prove problematic to the Church, as he noted in his annual report to Rome:

“Without counting the multiplicity of Chinese

dialects, one can count seven in the parish of Fr

Gazeau (Sts Peter and Paul). A big [sic] difficulty

is felt more and more. In fact, there are three

distinct classes of Chinese in Singapore: Those

who were born in China; those who are born

in Singapore and converse in Chinese; and the

Straits-born Chinese (Peranakans). Several in

this last group have already cut off the tresses

of their hair”.16

By the last decade of the century, the Cantonese and Hakka Christians at Sts Peter and Paul had grown so numerous that they began clamouring for a church of their own. In 1895, after a short visit by a Cantonese priest from China, the Cantonese Christians of Sts Peter and Paul called for the creation of a parish of their own. They were granted their request, and a separate Cantonese Mission was created in 1895 with its own services, although they remained under the same roof with the others at Sts Peter and Paul.17 Yet, the desire for separate premises was still very much hoped for.18 Hence, a piece of land at Wayang Street was purchased in 1897 to build the new church. Three prominent members of Sts Peter and Paul: Chan Teck Hee, Low Kiok Chiang and Chong Quee Thiam, each paid a third of the total cost of the land which amounted to $16,000.19

The Mission decided to place the Hakka Christians with the Cantonese in this new church dedicated to the Sacred Heart of Jesus.20 However, due to some complications, the property was sold and the present one at Tank Road was purchased in 1903. Although a public subscription was started for the building of the main church, the Mission still had to depend on the generosity of Chan Teck Hee to erect the church’s presbytery cum orphanage in 1906.21 The foundation stone of the church was laid on 14 June 1908, and by 11 September 1910 Sacred Heart Church was completed, blessed and opened.

With the separation of the Chinese Mission a fait accompli, the further development of the Cantonese-Hakka Catholic community thus commenced. Aside from having their own place to congregate, their own schoolhouse cum orphanage, sermons were also given in their own Cantonese-Hakka vernacular. The creation of a collective identity for their community was thus made possible, and this certainly had the effect of rooting down more Chinese Christians to Singapore. By the mid-1920s, the CantoneseHakka church had grown to 1,300 adherents.22 The departure of the non-Teochew Christians from Sts Peter and Paul left the seat of the Singapore Chinese Catholic Mission even more Teochew in character.

The Hokkien Christians were the last of the Sts Peter and Paul community to establish their own community. There were only several hundred of them in Singapore in the early 1920s, and conversions among them were very rare.23 Evangelical work with the Hokkien Christians began as early as 1902, when the Mission acquired a property six miles east of town where Fr R Cardon gathered his small Hokkien Catholic community.24 In 1912, when a wave of Chinese nationalism swept through Singapore following the 1911 Republican Revolution in China, anti-foreign sentiments once again flared-up among some Chinese in Singapore. The Catholic Church once again came under the harassment of Chinese secret societies as they considered the Church a Western institution. The Hokkien Catholics were subjected to daily taunting, and their mission outpost was vandalised. A well-to-do Hokkien Catholic was also set upon and nearly killed.25 By that time, the French Mission was convinced that the Hokkien Catholics needed a church and enclave of their own, or no Hokkien Catholic community would ever be rooted. However, no concrete step towards this goal was taken till after World War I.

The land to build a church for the Hokkien Christians was finally acquired by Fr EJ Mariette on 21 November 1925. Located at Bukit Purmei, just west of town, it cost the Mission $26,000.26 Fr Mariette, with the assistance of Fr Stephen Lee, then rallied of the congregation of Sts Peter and Paul to contribute all they could for this new endeavour.27 And just as it was with the Church of the Sacred Heart, it was the prominent Catholics of Sts Peter and Paul who once again came to the aid of their Hokkien brethren. A church building committee was convened at Sts Peter and Paul on 15 December 1925 where eleven of the wealthiest Chinese Catholics of the island were roped in to lead the subscription efforts. The contract cost of this new church was estimated to be $211,000.28 As the amount was staggering, the Bishop withheld his approval for the contract till the priests of the Chinese Mission could assure him that the sum could actually be obtained. At this juncture, it was Chan Teck Hee who came to the rescue once more, offering to stand as guarantor for the unpaid pledges of the subscription.29

It was Fr Lee who finally completed the new parish, dedicated to St Teresa, in 1929, as Fr Mariette had died a year earlier in a fatal accident at the construction site.30 Following the completion of the main church, a doctrine house was erected on 6 October 1929 at a cost of $5,000 which was entirely paid for by Wee Cheng Soon, another prominent personality from Sts Peter and Paul. The doctrine house, aside from functioning as a presbytery, was also the church’s “Memorial Hall” and residence of the parish’s HockChia catechist. Fr Lee also made it the Mission’s Catholic “Hokkien Hui-Kuan”.31 However, this new edifice remained dormant for several years before the Bishop could spare a priest to be its resident vicar. Besides, many of the Hokkien Catholics were still congregating in the east of the sland, near the original Hokkien mission station.32 Hence, masses at St Teresa were celebrated only on Sundays and on feast days, and seldom with the church filled. There was no “parish” assigned to this new church till April 1935, when Fr Lee himself was posted there as parish priest.33 The missionaries’ solution to the slow growth of the Hokkien Mission was to build around St Teresa’s, a new Catholic enclave.

In 1934, the Chinese Mission acquired approximately seven acres of land on Bukit Purmei hill to build a Catholic village that was eventually named Bukit Teresa.34 The village began with just six bungalows and ten barrack houses, which the Church had built and sold to parishioners. In the midst of these houses, the Mission added a Convent that was given to the Carmelite nuns from Bangkok. Similar to the Chinese Catholic communities of Malacca and Pontian, at Bukit Teresa, Catholic families were relocated from town to settle in this new Catholic colony, thereby entrenching a rooted Catholic community around the church. By 1935, when St Teresa was officially designated a parish, Fr Lee had 450 parishioners coming for masses, a significant number considering that there were only a couple of hundred Hokkien Catholics in the mid-1920s.35 Clearly, in the case of St Teresa’s, to root a Catholic community, it was not enough to separate dialectal communities and give them their own places of worship. It was also necessary to gather these communities within enclaves where social-communal institutions could be established to foster a sense of belonging to the community.

Following the success of the Chinese Catholic enclaves, the Eurasian Catholics had also established their own church in suburban Singapore after the turn of the century.

Since the 1830s, the Eurasian Catholics have shared the Cathedral of the Good Shepherd with all other ethnic groups.36 Though the Asiatic Christians were eventually separated from the parish of the Good Shepherd after the completion of Sts Peter and Paul, the Cathedral continued to house a cosmopolitan mix of Catholics from all over Europe. There were even scores of Japanese converts baptised at the Cathedral till the 1930s, and this figure does not include the Catholic arrivals from Japan.37 The Eurasians thus, till then, had no parish of their own. By the mid-1890s, the Cathedral had 2,000 parishioners, including several hundred Eurasian families with hundreds of children in the town schools.38

From 1902, when the completion of Tanjong Katong Road made access from town to the East Coast district easier, a large number of the town Eurasians settled themselves in this suburb, six to seven kilometres from town, turning it into a Eurasian enclave.39 However, it was only in 1923 that the MEP was able to erect a chapel for the Eurasians at Katong.40 In time, just as with the other Catholic enclaves in Singapore, social-educational institutions were also developed around the Katong parish. By 1935, there were 1,500 parishioners at the Katong church, and they had more than 600 children enrolled in the Katong Brothers’ and Convent school.41

Another sign that a more indigenised Catholic community had already been rooted in Singapore prior to World War II was the emergence of ethnic-based fraternities and welfare organisations within the Church.42 In 1917, Chinese and Indian Christians of the Mission came together to found the Catholic Union, a pan-ethnic social action organisation that brought the Mission’s Asiatic Christians together.43 By 1922, the Catholic Union was entirely constituted by the Chinese Christians while the Indian Christians went on to form their own Catholic Young Men’s Association in 1928.44 At the Serangoon parish, the St Joseph’s Dying Aid Association was established in 1926 to aid parishioners in times of bereavement.45 The Indian Christians too had their very own funeral association, the Indian Catholic Benevolent Society, which they founded in 1914.46

Although this trend towards communal self-help was typical of ethnic-oriented trend of development within the Church in the pre-war years, communal separation did not amount to discriminatory segregation. Perhaps, what is pertinent here is that the communal Church had begun sharing the traditional social-welfare functions of the French clergy, the same functions that had indigenised the institutional Church. Hence, it can be seen that among the ethnic Christian communities, a sense of communal “ownership” of the Church had already arisen in the prewar years. When Fr Stephen Lee was entrusted with the stewardship of the whole Chinese Catholic Mission in 1929, following the death of Fr Mariette, an indigenous clergyman was placed solely in-charge of the Chinese Catholic community for the first time.47

In Retrospect

Though throughout the 19th century the Church in Singapore was fundamentally multi-ethnic, Church growth was mainly dependent on the addition of Chinese Christians to the Mission. It was in no small part due to the Mission’s concerted effort in fostering the creation of families among the Chinese Christians, and the subsequent emergence of Catholic communal enclaves across the island, that it was possible for the Church to reach a certain level of maturity. By the turn of the century, the Chinese Catholic community had grown so large and dialectally diverse that it became necessary to allow for divergence in the hitherto singular Chinese Mission.

Hence, the Church began its next phase of development by forming parishes along ethnic-dialectal lines, a strategy that was greatly aided by the Mission’s founding of communal enclaves around each established parish. In essence, the desire for communal division by the dialectal subgroups within the Chinese Catholic community was also in reality their expression of communal self-identity vis-a-vis others in the Church. Clearly, a more indigenised Chinese Catholic community had taken root in Singapore at the turn of the century. In retrospect, the emergence of this community in Singapore in the pre-war years was the outcome of social evolution as well as the fruit of institutional action.

A more localised Catholic community had emerged in Singapore by the early 20th century, decades before the notion of nationhood was conceived on the island. In its transition to find a niche in a society that was in transition itself, the Singapore Catholic Church had become more than just a component within the wider pre-war colonial order. The emergent Church was more than just a religious community. It had become a visible and self-generating social community.

PhD candidate

National Institute of Education, Nanyang Technological University

NOTES

-

At Bukit Timah, the land exhaustion of the 1850s led most of the district’s Teochew Catholic agriculturists to re-migrated elsewhere. Yet, a small community of several hundred always remained at the Bukit Timah parish, partly due to the fact that they resided on parish land and that the parish still had 40,000 rubber trees that kept them employed. See Annales des Missions Etrangeres, Malaisie (An ME), Archives de la Societe des Missions Etrangeres de Paris, 1907–1911, 305. ↩

-

Archives de la Missions Etrangeres (AME 905/342), 1883–1884; 906/111, 1903–1904; 906/180, 1916. ↩

-

Phang Lee Kiong, “The Development of the Teochew Community in Kangkar, Upper Serangoon Road - Migrants Adjustability and Social Change” (Bachelor’s theses, National University of Singapore, 1971), 34, https://scholarbank.nus.edu.sg/handle/10635/238211. ↩

-

Compte Reudu (CR), Malaisie, 1892, 203–10. ↩

-

Straits Settlements, Straits Settlements Government Gazette, June 1910, 1305–06. (Call no. RRARE 959.51 SGG; microfilm NL1232) ↩

-

Phang, “Teochew Community,” 34. ↩

-

Phang, “Teochew Community,” 34. ↩

-

An ME, 1906, 237–39. ↩

-

CR 1922, 123–28. ↩

-

CR 1921, 105–10; CR 1925, 113–18. ↩

-

Straits Settlements Annual Report, Education Reports and Appendices, 1860–1870. From an annual average of 25 Indian Christian boys enrolled at the school in the 1860s, the number rose to 36 in the 1870s. ↩

-

AME 905/373, 1886; CR 1885, pp.108–12. ↩

-

CR 1886, pp.112–16; AME 905/365, 5 Jun 1885; 905/379, 7 Feb 1887 and 905/410, 10 May 1888. The presbytery was erected in 1887, with the ground floor occupied by the new Anglo-Tamil Mission School. Sir Frederic Weld, Singapore’s first Catholic governor, helped to secure the land. Our Lady of Lourdes was not unlike the Chinese Catholic enclaves in the interior of Singapore where the creation of close-knit communities had become catalytic to Church growth. By 1892, there were 750 Indian Catholics on the island. See AME 906/50, 1893. ↩

-

AME 905/342, 1884; 906/99, 1901. ↩

-

CR 1889, 189–91. ↩

-

CR 1904, 215–22. ↩

-

“Benediction”, speech written by Fr Gazeau in September 1910 on the occasion of the blessing and opening of the Church of Sacred Heart– found written in the last pages of the parish’s first Confirmation Register. ↩

-

CR 1897, 206–20. ↩

-

Gazeau, “Benediction.” ↩

-

CR 1898, 198–211. ↩

-

Gazeau, “Benediction”; Church of the Sacred Heart, 75th Anniversary Souvenir (Singapore: Church of the Sacred Heart, 1985), 14. Chan Teck Hee had also provided the building material of the church. ↩

-

CR 1927, 124–30. ↩

-

CR 1924, 103–07. ↩

-

CR 1902, 212–24. ↩

-

CR 1912, 239–49. ↩

-

CYMA Church of St. Teresa, St Teresa Souvenir (Singapore: Catholic Young Men Association, St Teresa’s Church, 1947), 19. (From PublicationSG) ↩

-

CR 1926, 128–34. ↩

-

CYMA Church of St. Teresa, St Teresa Souvenir, 21–22. ↩

-

“The Church of St Teresa,” Stephen Lee’s Manuscript Journal, 6 December 1926. ↩

-

“The Church of St Teresa,” Lee was made head of the Chinese Mission upon from Mariette’s death, 13 March 1928. ↩

-

“The Church of St Teresa,” 1929. ↩

-

“Baptism Registers,” St Teresa’s Church, 1929–1934. ↩

-

Lee, “St Teresa’s”, 6 April 1935. ↩

-

CYMA Church of St. Teresa, St Teresa Souvenir, 53. ↩

-

Lee, “St Teresa’s.” ↩

-

When Rome restored the Diocese of Malacca in 1888, the Vicar Apostolic of Malaya was then conferred the title of Titular Bishop. The Church of the Good Shepherd was then officially renamed a Cathedral. ↩

-

Baptism Registers, Cathedral, 1906–1930s. There were no Japanese names on the baptismal registers of any other parishes before the war except at the Cathedral. The Japanese Christians, though Asians, were unlikely to have been welcomed at the Chinese parishes during this period of Chinese anti-Japanese sentiments. ↩

-

CR 1896, 256–60; SSAR 1893, 323–30. ↩

-

Myrna Braga-Blake and Ann Ebert-Oehlers, eds., Singapore Eurasians: Memories and Hopes (Singapore: Times Editions, 1992), 61. (Call no. RSING 305.80405957 SIN) ↩

-

Braga-Blake and Ebert-Ohlers, Singapore Eurasians, 61. This chapel was demolished in 1932, and the present one erected. ↩

-

Straits Settlements, Blue Book (Singapore: Govt. Print. Off., 1930), 638, 648. (Call no. RRARE 315.957 SSBB). In 1930, the town Convent founded a branch of their school at Katong, and the Brothers followed suit by converting their bungalow there into St Patrick’s School in 1933. ↩

-

A discussion on how fraternities were aspects of a mature community can be found in Phelan, The Hispanization of the Philippines, 74. There were several social welfare associations formed within the Church before 1900, the St Vincent de Paul Society and the Singapore Catholic Funeral (Benevolent) Association. Though a third of the SCBA membership was non-Eurasian, it was a Eurasian-dominated organization. See The Singapore and Malayan Directory (Singapore: Fraser and Neave, 1922), 97 (Call no. RRARE 382.09595 STR; microfilm NL1191–NL1193); Singapore Catholic Benevolent Association, Management Committee’s Report and Accounts For 1922 (Singapore: CA Ribeiro, 1923), 7–11. ↩

-

Singapore and Straits Directory_ (Singapore: Fraser and Neave, 1919), 107; “Clubs, Societies and Associations,” The Singapore and Malayan Directory (Singapore: Fraser and Neave, 1927). (Call no. RRARE 382.09595 STR; microfilm NL1191–NL1193) ↩

-

SMD 1922, 96; 1940, 1023. ↩

-

SSBB, 1926, Friendly Societies, Section 30. ↩

-

Straits Settlements Executive Council Minutes, 24 Jul 1913, 525. ↩

-

It has been observed that in a Mission, indigenous Christians, who were ordained ministers, were still regarded as assistants to the foreign missionaries. See Christian Neill, Missions, 515. Fr Lee was assisting anyone in 1929. ↩