Eyes on Nature: The Glorious Periods of Picturing Natural History

The mere mention of the Malay Archipelago conjures up images of amazing rare things and nature’s paradise. During the 17th century, the term “natural history illustration” came into use as artists created images of plants and animals for documentation and study. Early Europeans who had studied the flora and fauna of the region include Stamford Raffles, William Farquhar, William Marsden and Alfred Russel Wallace.

— Stamford Raffles writing from Southern Sumatra to the Duchess of Somerset in July 1818. Quote extracted from Archer, M. (1962). Natural history drawings in the India Office Library. London, Published for the Commonwealth Relations Office by H.M. Stationery Off.

To the early naturalist, the mere mention of Malay Archipelago conjures up images of amazing rare things and nature’s paradise. Interest in natural history in this region corresponded with the energetic intellectual climate in early modern Europe. During the 17th century, the term natural history illustration came into use as artists created images of plants and animals for documentation and study. Many European ships set sail for journeys of discovery during that period. The travelling naturalists responded to the flora and fauna and to the landscapes, in which they worked.

Rendering the nature’s elegance and beauty has a long history. Dating as early as 30,000 years ago, the oldest “scientific” records can be seen from the French caves. Pictures of ancient Egyptians sacrifice and Leonardo da Vinci’s sketches of human bodies are notable forms of early scientific drawing. There are also vivid descriptions of exotic flowers in the South East Asia including the Rafflesia arnoldi, the world’s largest flower and the Orchideous plant, discovered by Sir Stamford Raffles.

Painting on Cave Walls

Primitive men are credited with painting on cave walls at Lascaux in France, long before civilisation. Animal figures such as the horses, bison, rhinoceroses, lions, buffalo and mammoth have been seen. These amazingly accurate drawings seem to indicate that the observers had studied the subject intensely and reproduced the images from memory in dimly lit caves. The meaning and purpose of cave paintings are complicated and varied. Some images record mythological stories, sorcery, fertility and rituals, while others depict hunting scenes. It was believed that drawing a particular animal would invoke the species to propagate and the ritual act of painting or touching these depictions would release sacred energy or power. Visual aids such as arrows have also been seen next to some drawings and could have been used to train the young cave dwellers.

Animals played a big part in the lives of the early cultures. They are among the first drawings that human depicted. Various art forms have shown animals in their symbolising power and influences. There are certain degrees of similarity among these animal portrayals. Most animals are shown in broadside view to provide the most information. Birds, quadrupeds and fishes show their most salient characteristics from the side whereas insects and arthropods reveal most of theirs when seen from above.

Tomb Murals and Greek Pottery

The ancient Egyptians (5000–300 BC) lived on high ground along the banks of the Nile River and were cattle- raisers or farmers. Drawings on buildings, sculptures, papyri, coffins and burial tombs revealed the rich tapestry of Egyptians’ relationship with nature and their beliefs, such as “life after death”. One famous depiction showing a person’s judgment of the afterlife is the Weighing of the Heart, where the jackal-headed god Anubis is weighing the heart of a priestess. The scale illustrates one example of “ancient technology”.

Ancient Greek (1500–31 BC) was particularly famous for their vases, sculptures and architecture. Early portrayal of “scientific apparatus” of the era has shown transport, hunting tools and techniques of weaving cloths. This period also marked the beginning of humans and monumental stone sculptures. Human statutes are heroically proportioned due to Greek humanistic belief in the nobility of man. By the time Alexander the Great died at 323 BC, the Greek sculptors had mastered carving marbles and were technically perfect. They sculpted heroic human figures that still remain popular today.

Chinese Animal Motif and the Mughal Painting

Chinese arts are greatly influenced by nature. Painting of birds, flowers, and landscapes from the countryside were popular. The earliest images of animals are produced during the Shang Dynasty (1523–1028 BC). Animal motifs such as cicada, owl, bear, rabbit, deer, even tapir and Indian rhinoceros are carved in jade or cast in bronze. Two and more animals are often combined in a single artwork, representing the “metamorphosis of one animal into another”. Animals are not the subjects of interest as living creatures but are for aesthetic and decorative purposes. The Chinese also like to depict animals with symbolic meaning. For example, fantasy animals such as dragon and phoenix with flames (symbolising power) streaming from their bodies and cranes and zodiac animals (symbolising long life).

Graphic art started after paper was invented in AD 105. Although no painting on paper survived from the early Han period (206 BC–220 AD), stylised animal pictures preserved on damask and other textiles are found. Chinese ceramics such as those in Tang Dynasty (AD 600– 900) achieved its finest artistic standard; for example, the standing figures of spirited horses.

Hunting scenes, common in many prehistoric illustrations are also found in India. Religious life of the Hindus (namely Buddhism and Hinduism) greatly influences the Indian arts. Human figures are glorified and most animal representations (elephants and cattle are fairly common) are sculpted in stones.

Realistic and detailed paintings came about from the 16th century. Monarchs at the time, such as Akbar the Great and his son, Jahangir were very passionate about painting and the natural world. The Mughal School of painting came into being. One famous artist, Mansur was known as the “painter of flora and fauna”. He travelled with the emperor and created famous images of zebra, neelgai (a kind of deer) and a variety of birds.

Artists as Scientists from Early Modern Europe

Around 1400, artists in Europe began to produce more “realistic” or “naturalistic” style of drawing. During this period, scholars were increasingly interested to study, collect and classify living things. Many captivating drawings are produced and used as identification aids, religious symbols and philosophical ideas or purely for art appreciation. Over the next two centuries, this new approach to nature came to be known as “scientific illustration”.

A man of “both worlds”, Leonardo da Vinci (1452–1519) was an artist, scientist, engineer and inventor. He would dissect corpses and record everything he found in his journals. His images of animals, plants and human bodies are results of careful observation of natural structures, forms and compositions.

One of the greatest painter-naturalists of her time was Maria Sibylla Merian (1647–1717). She created beautiful visual images of flowers and insects and her observations revolutionised the science of animals and plants. Her works are rich with tropical flowers and fruit, insects of all kinds, especially exotic butterflies, moths and caterpillars.

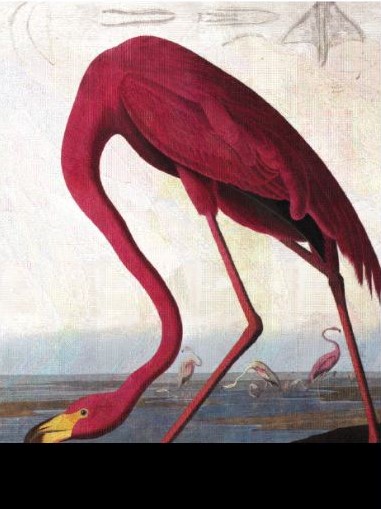

Another well-known water-colourist, naturalist and adventurer whose name is synonymous with bird and nature lover and environmentalist was John James Audubon (1785–1851). His passion for birds resulted in a seven-volume edition of The Birds of America describing the anatomy, habits and localities of the birds with 500 hand-coloured lithographs.

For centuries, artists have worked closely with the “natural scientists”. Andreas Vesalius (1514–1564) worked with artist, Jan van Calcar in the seven-volume, revolutionary human anatomy textbook, De humani corporis fabrica. Woodcut designer, Hans Weiditz and botanist, Otto Brunfels (1488–1534) produced stunning plant studies in Herbarium vivae eicones. A team of craftsmen and Leonhard Fuchs (1501–1566) who was a physician and botanist, created the early printed herbals, De historia stipium.

Voyages and journeys of exploration became common in early modern Europe. These ships travelled around the world in search of scientific discovery. Skilled artists usually went along and produced amazingly illustrated botanical and natural history books. English painter, Augustus Earle (1793–1838) embarked with Charles Darwin (1809–1882) in one of the world most famous expedition, HMS Beagle. Darwin had no artistic flair and depended on Earle to illustrate the materials that he collected both at sea and ashore.

Fusion of Western and Eastern Natural

Shortly before the 19th century, the British East India Company began to explore Asia. Great numbers of its staff moved from England in search of new trading ports.

In India, these newcomers who have arrived on the exotic land were fascinated by what they saw. They purchased paintings that depicted daily life, important monuments and local flora and fauna. Indian artists were quick to offer what these new patrons wanted. They modified traditional techniques to suit Western tastes. The resulting hybrid of Indian and European styles and painting techniques came to be known as the “Company Painting”.

Calcutta (Kolkata) was the oldest trade houses of the East India Company. It was also an early production centre for natural history paintings. The city’s enthusiastic patrons include Marquis Wellesley, governor-general from 1798 to 1805 and Major-General Thomas Hardwicke of the Bengal Artillery (1755–1835). Both men collected large menageries and hired artists to paint the birds and animals and other specimens they acquired. A Company-established botanical garden in Calcutta also undertook similar project for the plant samples it had collected.

Another influential painting centre was in Madras where Lord Clive, eldest son of Robert Clive was stationed. While in the army, Lord Clive, a naturalist devoted his time to pursue his interest and produced several volumes of natural history paintings from South India.

European traders have also enjoyed access to China in the late 17th century. Like the Indian counterparts, Chinese artists who worked at the foreign settlement at Canton (Guangzhou), were quick to adapt their talent to produce detailed botanical paintings that suited the Western clients.

detailed botanical paintings that suited the Western clients. China has a well-established system of modular painting techniques. The Mustard Seed Garden Manual of Painting (Chieh Tzu Yuan Hua Chuan) is one of the greatest manuals on painting. It gives hundreds of examples of the brushstroke forms, ranging from single stroke of a blade of grass or flower petal to the composition of a tree, village and mountain. These superior examples explain the principles and standards of painting. An artist could creatively combine each module in different ways with almost limitless variation in his work. This also explains why the Chinese artists could adapt their skills easily to create botanical drawings to meet the export markets.

Early Naturalists in the Malay Peninsula

The East India Company has one of the largest natural history drawings. They realised the economic and scientific value of plant and animal products. Thus, overseas officials were encouraged to pursue their interests in natural history.

After the British conquest of Java in 1811, Stamford Raffles (1781–1826) was promoted to become the lieutenant governor. In 1819, he founded Singapore by purchasing the land for the British East India Company. Raffles was an enthusiastic natural historian. While travelling on his assignments, he encountered the unusual natural and stunning landscapes. Raffles hastened to collect and record the images of the objects he found with proper scientific data. This resulted in a plethora of dried plants and insects, skins of birds and animals, shells and minerals and a series of their paintings by Chinese painters.

Raffles would carefully organise and dispatch crates of specimens back to England. However, few of these collections have survived and these are now preserved at the British Museum. A fire broke out and destroyed everything that he had collected on his boat when he left Sumatra for home in 1824.

A friend of Raffles, William Marsden (1754–1836) who was stationed in Bencoolen in Sumatras has a broad interest in the local history, cultures and language. He was also keen in natural history and frequently wrote to British scientists. Marsden was a source for many of our most precious botanical and zoological drawings from his time.

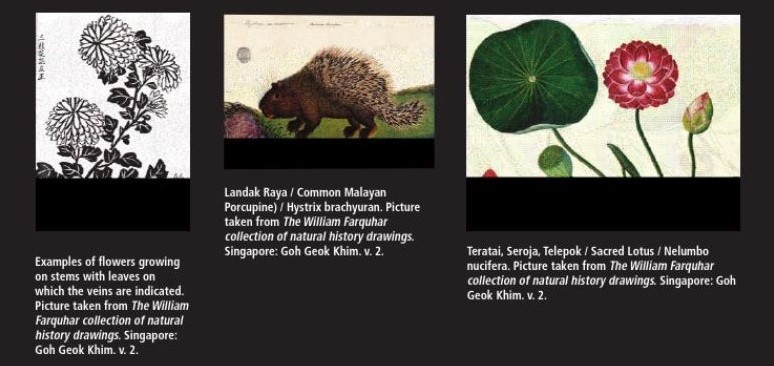

William Farquhar (1770–1839) has long been associated with Stamford Raffles. He was the first British Resident and Commandant of Singapore in 1819. He was also a naturalist and passionate investigator. While in Melaka (Malacca) from 1795 to 1818, Farquhar employed the locals to collect and preserve the specimens and commissioned Chinese artists to paint them. The paintings show a charming combination of traditional Chinese painting aesthetics and a high standard of scientific detail. He would send the drawings, detailed descriptions, bones, preserved specimen, particularly unknown foreign species to the attention of museums, botanic gardens and naturalists. He made many important zoological discoveries, among them the Malayan tapir, binturong, banded linsang, bamboo rat and moonrat.

Farquhar brought his collection of drawings with him to Singapore and from there to London. He presented the collection to the Royal Asiatic Society (RAS) in 1827. Mr Goh Geok Khim, a stockbroker by profession and a nature lover, acquired the entire collection of watercolour painting in an auction in 1993. He officially donated it to the Singapore History Museum in 1996.

The person, who shared Darwin’s discovery of evolution was Alfred Russel Wallace (1823– 1913). Wallace made extensive trips to the Amazon River basin and then the Malay Archipelago. He arrived in the East in 1854 as an experienced collector and never lost his excitement at seeing new things and making new discoveries. More than 125,000 specimens (including 80,000 beetles alone) were collected in the Malay Peninsula. During the field trips he observed the differences between animals in Asia and those in Australia. Delicate pencil sketches and drawings of those newly discovered species were among Wallace’s collection.

Uses of Art in the Service of Science

Prehistoric men communicated their religion, law and history through painting and carving long before written language was developed. Various art forms, including song, dance and storytelling were not merely used for ceremonial performance or enjoyment but as a mean of recording ideas and values.

From the Lascaux cave art of France, through Merian’s secrets of insect metamorphosis to Leonardo’s anatomical studies, pictures and diagrams have made learning science more interesting and meaningful than text alone can provide. Natural history drawings also reveal the natural environment of our rich past and present in a creative way.

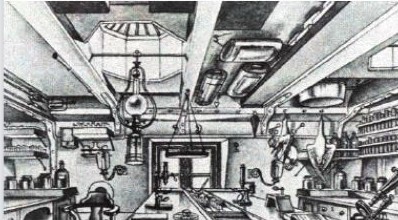

Drawing and painting plants are among the earliest uses of art for scientific purposes. The Greek physician, Pedanius Dioscorides who was born in the first century AD, compiled De materia medica. He showed vividly how drugs were prepared from plants and their chemical properties. It became the most central pharmacological work in Europe and the Middle East.

Exotic objects were collected from the Western ships coming back from the New World—Asia, Middle East and Africa. These were kept in “cabinets of curiosities” and became the forerunners of modern museums. Famous collectors include the “greatest naturalist of his times”, Conrad Gessner (1516–1565) and Ulisse Aldrovandi (1522–1605) who organised numerous excursions to Italian mountains, countryside, islands and coasts in order to collect and catalogue plants.

The 18th century witnessed infectious interest in the study of natural history among the amateurs and scientists. It became part of liberal education among men and women. It was also the golden age of Carl Linnaeus (1707–1778). He was curious about the natural world and wanted to “bring order to nature”. He went on to name, rank, and classify the living things using his naming convention known as the “binary nomenclature”, which is still widely used today. Natural history drawing has been important in showing the general characteristics of the species such as shapes and colours and is essential for systematic classification.

Charles Darwin kept many specimens during his amazing journey aboard the Beagle where he made observations that led to his revolutionary theory of natural selection. His book, On the Origin of Species became a pivotal work in the scientific literature. Another famous expedition, the Challenger of 1874 witnessed the birth of oceanography, as it is known today. Among the new discoveries made, the expedition catalogued 4,000 previously unknown species of animals. These specimens were examined, identified and drawn. The expedition also reflected a deep collaboration among natural historians, ocean specialists and artists.

Conclusion

The wonder and beauty of nature has been richly documented for thousands of years. Delineation of the living world reaches its heightened accuracy in the late 18th century when advanced printing methods such as stipple engraving and lithography were used. The creators of natural history drawings often find the field an ideal fusion of interests in art and science. As Wilfrid Blunt expounded, “The greatest flower painters are those who have understood plants scientifically, but have yet seen and described them with the eyes and the hand of the artist.” Blunt (1994).

Senior Librarian

Lee Kong Chian Reference Library

National Library

REFERENCES

Alfred Russel Wallace, The Malay Archipelago: The Land of the Orang-Utan, and the Bird of Paradise (Singapore: Oxford University Press, 1986). (Call no. RSING 959.8 WAL)

Brian J. Ford, Images of Science: A History of Scientific Illustration (London: British Library, 1992). (Call no. RART 743.93 FOR)

David Attenborough et al., Amazing Rare Things: The Art of Natural History in the Age of Discovery (London: Royal Collection, 2007). (Call no. R 508.0222 ATT)

Images From Nature: Drawings and Paintings From the Library of the Natural History Museum (London: The Natural History Museum Publishing Division, 1998). (Call no. RART 758.4 IMA

Kwa Chong Guan, “Drawing Natural History in the East Indies,” in The William Farquhar Collection of Natural History Drawings, vol. 1. (Singapore: Goh Geok Khim, 1999), 27–35. (Call no. RSING q759.959 WIL)

Mildred Archer, Natural History Drawings in the India Office Library (London: Published for the Commonwealth Relations Office by H.M. Stationery Off., 1962). (Call no. RART 743.6 ARC)

S. Peter Dance, The Art of Natural History: Animal Illustrators and Their Work (Woodstock, N.Y.: Overlook Press, 1978). (Call no. RART 741.6 DAN)

Sherman E. Lee, A History of Far Eastern Art (London: Thames and Hudson, 1997). (Call no. RART q709.5 LEE)

The William Farquhar Collection of Natural History Drawings, vols. 1 and 2. (Singapore: Goh Geok Khim, 1999). (Call no. RSING q759.959 WIL)

Tony Rice, Voyages of Discovery: Three Centuries of Natural History Exploration (London: Natural History Museum/Scriptum Editions, 2000). (Call no. R q508.09 RIC)

Wang Gai, The Mustard Seed Garden Manual of Painting (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1977)

Wilfrid Blunt and William T. Stearn, The Art of Botanical Illustration (Woodbridge: Antique Collectors’ Club, 1994). (Call no. R 581.0221 BLU)

FURTHER READINGS

Bernard Smith, Imagining the Pacific: In the Wake of the Cook Voyages (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1992). (Call no. R q910 SMI)

Elaine R.S. Hodges, et al., eds., The Guild Handbook of Scientific Illustration (Hoboken, N.J.: John Wiley, 2003). (Call no. R q502.22 GUI)

Fritz Koreny, Albrecht Dèurer and the Animal and Plant Studies of the Renaissance (Boston: Little, Brown, 1988). (Call no. RART 759.3 KOR)

Gill Saunders, Picturing Plants: An Analytical History of Botanical Illustration (Berkeley: University of California Press in association with the Victoria and Albert Museum, London, 1995). (Call no. RART 743.7 SAU)

John James Audubon, Writings and Drawings (New York: Library of America, 1999). (Call no. R 598.092 AUB)

Robert Huxley, ed., The Great Naturalists (London: Thames & Hudson, 2007). (Call no. R 508.0922 GRE)

Sandra Knapp, Potted Histories: An Artistic Voyage Through Plant Exploration (London: Scriptum Editions in association with the Natural History Museum, London, 2003). (Call no. R 581 KNA)