A History More Refined: Malay Women’s and Men’s Magazines of the 1950s in Singapore and Malaya

This essay covers the historiography of Malay periodicals of the 1950s. Associate Librarian Kartini Saparudin elucidates the use of magazines as vital historical sources, and traces the history of magazines for women and men in Singapore.

Magazines As Historical Sources

Within Malaysian historiography, much has been written about official documents as a result of its focus on colonial policy and practice. However, as the domains of historical inquiries expanded, scholars began to pay more attention to the local society especially the countries in Southeast Asia.

In the past, scholars would argue that indigenous materials are scarce and inaccurate. Official records, which consist of letters, reports, policy papers, whilst helpful also have certain limitations. They were not focused on the ruled but the ruler. With the increase in nationalistic sentiments and developments towards nation-building in the 1950s, scholars began to contemplate more on the local history, which hitherto had been a neglected area of research.

Western scholars were also increasing calls for autonomous and indigenous studies of Asian history. This has implications on how history is being written and in the use of its sources. In the case of contemporary history of Singapore and Malaysia written and oral records can be used. Oral sources, however, are problematic in terms of the availability of interviewees and the element of memory. Historians have reached a consensus that oral sources are best used in accompaniment with written sources. While colonial records represent a type of written source, publications such as newspapers, literary works, journals and magazines are gateways to indigenous societies. Ironically, far more Malay newspapers have been produced in Malaya than English newspapers throughout the 20th century.1

There are differences between using newspapers and periodicals in historical inquiry. Newspapers are indispensable as they provide a wide coverage of events and developments of a certain place and time. A periodical’s usefulness lies in its specificity. Periodicals are targeted at a certain audience with specific objectives, and therefore contain thoughts of particular groups in a particular nation. Periodicals invite us to the weltanshauung (worldview) and mentalité (mentality) of groups in a community. The use of periodicals in historical enquiry is beginning to find its equitable place alongside newspapers. As Dr A.M. Iskandar posits, there were more than 400 different periodicals published in Malaysia throughout the 20th century until 1968.2 This phenomenon is compelling given that only a small group of Malay-medium students had university education. In this light, Malay periodicals are underutilised as historical sources.

In the decolonisation of Malaya, the crucial process of identity formation within a multicultural society had to be accompanied by the self-empowered need to modernise itself along western lines. The tumultuous period of nation-building in the 1950s necessitated the creation of a progressive and open society to fulfill this vision of decolonisation by modernisation.3 It was a bulwark against the rise of communism and communalism in Asia, particularly Singapore and Malaya.4 Benedict Anderson concisely outlines this phenomenon as “the convergence of capitalism and print technology on the fatal diversity of human language [which] created the possibility of imagined community, which in its basic morphology set the stage of the modern nation”.5

The proliferation of Malay periodicals, specifically political magazines, men’s magazines, women’s magazines, children’s magazines and educational magazines was an answer to the call for nation-building. It was a manifestation of the search of the new Malayan identity that Malaya and Singapore had taken on its path to independence. T.N. Harper’s The End of Empire and the Making of Malaya posit that the “capacity of the state to create identity is a central issue in modern Malaysian history”.6 He reveals that the search for the British vision of the “Malayan” in art and literature was somehow “defeated by an upsurge of explorations in ethnic and religious identity that emanated from networks within vibrant popular cultures in town”. This effectively means that the rise of consciousness in identities within Malayan communities had thwarted colonial attempts to create one. Magazines were manifestations of this search for the Malayan identity, the Malayan Malay identity.

How would the use of women’s and men’s magazines assist scholars in this respect? The identity formation of modern Malay women, shaped by women’s magazines, was part of the larger upsurge of the various explorations of ethnic and religious identities that successfully refrained state-led attempts to create a British Malayan one. At the level of racial politics, the formation of the “modern” was part of a greater desire to ensure that Malay women got ahead of women from other groups. Kristin Ross’ theory in the reverberating example of modernising French women in the 1950s, “let’s win over the women and the rest will follow… [was] to target the innermost structure of society”.7 Reinventing the home was reinventing the nation. Men’s magazines, on the other hand, promoted the impetus to modernise men along western lines while providing an out-of-bounds marker on what is permissible for their Malay/ Muslim identity.

History of Men’s & Women’s Magazines in Singapore

Brief History of Malay Print in Singapore

During 1876–1941, Malay publishing went through three different phases of Malay journalism. According to William Roff (1972), the first phase of Malay journalism occurred in the period 1875–1905. Non-Malays such as Straits-born Muslims (Jawi Peranakans) and Straits-born Chinese (Baba Peranakans) dominated the phase.8 Ian Proudfoot (Working Paper 1994) outlines that it was the Javanese who dominated the scene, not the Jawi Peranakans.9 Despite this revelation, the weekly Jawi Peranakan was a manifestation of this era as the longest-surviving periodical of its time (1876–1905).

The second phase (1906–16) of Malay journalism, according to Roff, was characterised by a rise of major “national” dailies as well as the appearance of religious journals. This was probably the first time that a pan-Islamic religious publication began to make its presence. These journals were both reformist and influential, and were unique to Singapore. Two publications were highlights of these genres. One was Utusan Melayu, first published in November 1907. It was the first “national” “daily” that was published thrice a week by Mohd Eunos Abdullah. The other was the monthly Al-Imam (1906), the first Islamic reform journal to be published in Southeast Asia. It was the most influential journal of its time.

The third phase (1917–41) saw a rise of new titles and new types of publications such as dailies and weeklies, religious periodicals, non-religious periodicals (association magazines, school magazines), literary periodicals, periodicals from “progress associations” such as clubs and societies and, lastly, journals of entertainment. It is worth deliberating on the “journals of entertainment” to understand the beginnings of popular magazines such as men’s and women’s magazines. These journals, which started appearing in the late 1920s, gave birth to men’s and women’s magazines later in spite of the interruption from World War II.

Roff identifies such light-hearted tendencies in otherwise sober journals of entertainment. He sees them as an attempt to produce content of a more entertaining nature. Although these were light in intent, the periodicals were mostly didactic. Lightweight popular knowledge such as humorous sketches, jokes and “Pak Pandir tales” were incorporated into the content of the journal. Some journals, though unrepresentative of its time, were characterised as “unashamed entertainment”. Examples of these suggestive periodicals were Suleiman Ahmad’s infamous monthlies such as Dunia Sekarang, Shorga Dunia, Melayu Muda and others. Their salacity provoked the religious authorities, resulting in the banning of these publications. Magazines of this nature were more accepted during the postwar period. A more well known and respectable of this light-hearted genre is Al-Ikhwan by renowned Sayyid Shakh al-Hadi.

Roff’s appraisal of the three different phases in Malay journalism from 1876–1941 is complemented by Hamedi Mohd Adnan’s elucidation of the period after. He categorises the ensuing period into two. These are the period of the Japanese Occupation of Singapore and Malaya (1941–45), and the postwar period up to the time of Malayan independence in September 1957 (1945–57). Hamedi explains the sociohistorical factors of the postwar period that made the birth of and reception to Malay periodicals a unique occurrence This period saw the wide circulation and publication of popular magazines in Malaya and Singapore.

This period saw the emergence of Singapore as a premium printing and publishing centre in the region. Singapore’s political, economic and cultural infrastructure was instrumental in the political, intellectual, cultural and economic revival of the industry. This was due to the existence of a significant professional printing and publishing class such as printers, publishers, writers, journalists and activists. In addition, the greater existence of capital and publishing/printing technological know-how in Singapore promoted Singapore’s position as a cultural hub greatly.

According to Hamedi, from the date of the Japanese surrender (15 August 1945) until September 1957, 145 Malay magazine titles were published in Singapore and Malaya. During the same period, 46 newspaper titles were also published.10 These figures were an improvement over the figures provided by Iskandar in 1973, which were 105 magazine titles and 26 newspaper titles respectively.11

Hamedi proposes three main reasons for the increase in the number of Malay periodicals in this period. The most important factor, he believes, was the official declaration of the Emergency of Malaya in 1948. The Emergency activated the mobilisation of Malay men for defence of the country. More and more Malay men entered the army and police, and as a result, the demand for leisure reading was very high. The need for light reading also arose from the men and women who were weary from the Occupation and the post-Occupation social turmoil in the community. This was also supported by a rise in rubber prices due to the eruption of the Korean War in 1949. The rubber boom was instrumental for the growth of the printing and publishing industry. Thirdly, he observes that there was a shift of focus and interest, from publishing the religious and the social to the entertaining and the popular, to meet the reading demands of the public.

Definition of Malay Women’s and Men’s Magazines

Women’s Magazines in the 1930s and 1950s

Since the early 1920s, the discourse of femininity in Malay women was more developed in periodicals such as association and professional periodicals. Meant for teachers and largely influenced by the rise of reformist and religious journals in the region, the discourse was largely didactic, which was no different from other subjects discussed in Malay print.

Hamedi loosely defines women’s magazines as periodicals meant for women. This includes religious, nationalistic, literary, educational, association and organisational periodicals, and entertainment magazines (Hamedi, 2002, p. 46). Hamedi identifies seven women’s magazine titles: Ibu Melayu (October 1946), Putri Melayu (June 1947), Ibu (January 1952), Wanita (August 1956), Bulan Melayu (June 1930), Dewan Perempuan (1 May 1935) and Dunia Perempuan (15 August 1936). He observes that three of them were produced during the prewar period.

Departing from Hamedi’s broad definition of women’s magazines we can redefine them to be mass-circulated commercial magazines, which target women as consumers and agents of change in the households and community. These contain information on fashion, sentimental fiction and modern etiquette, and advertisements.

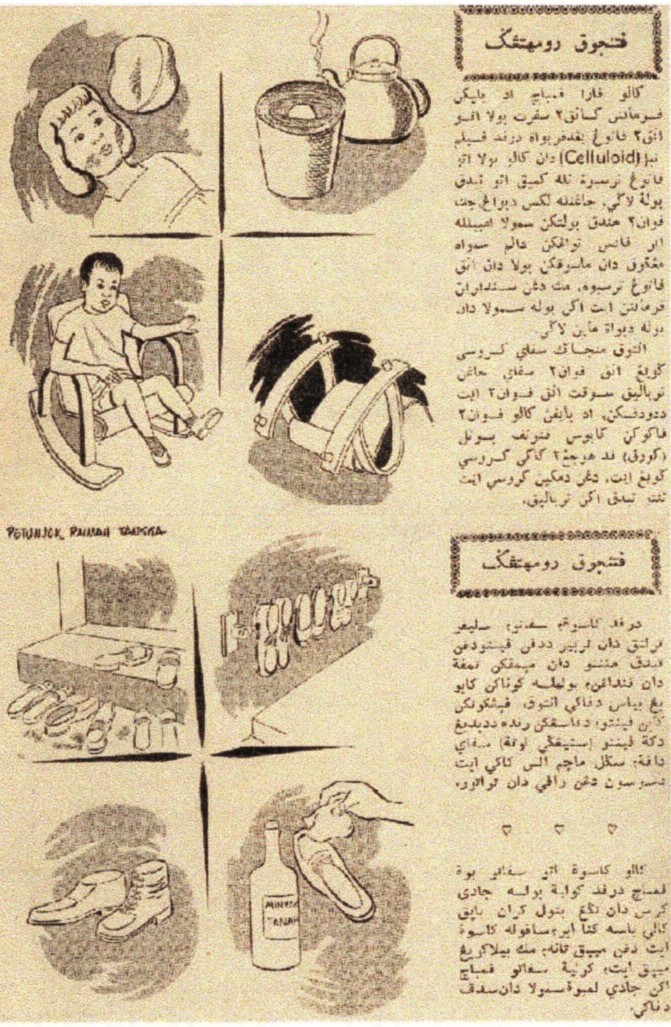

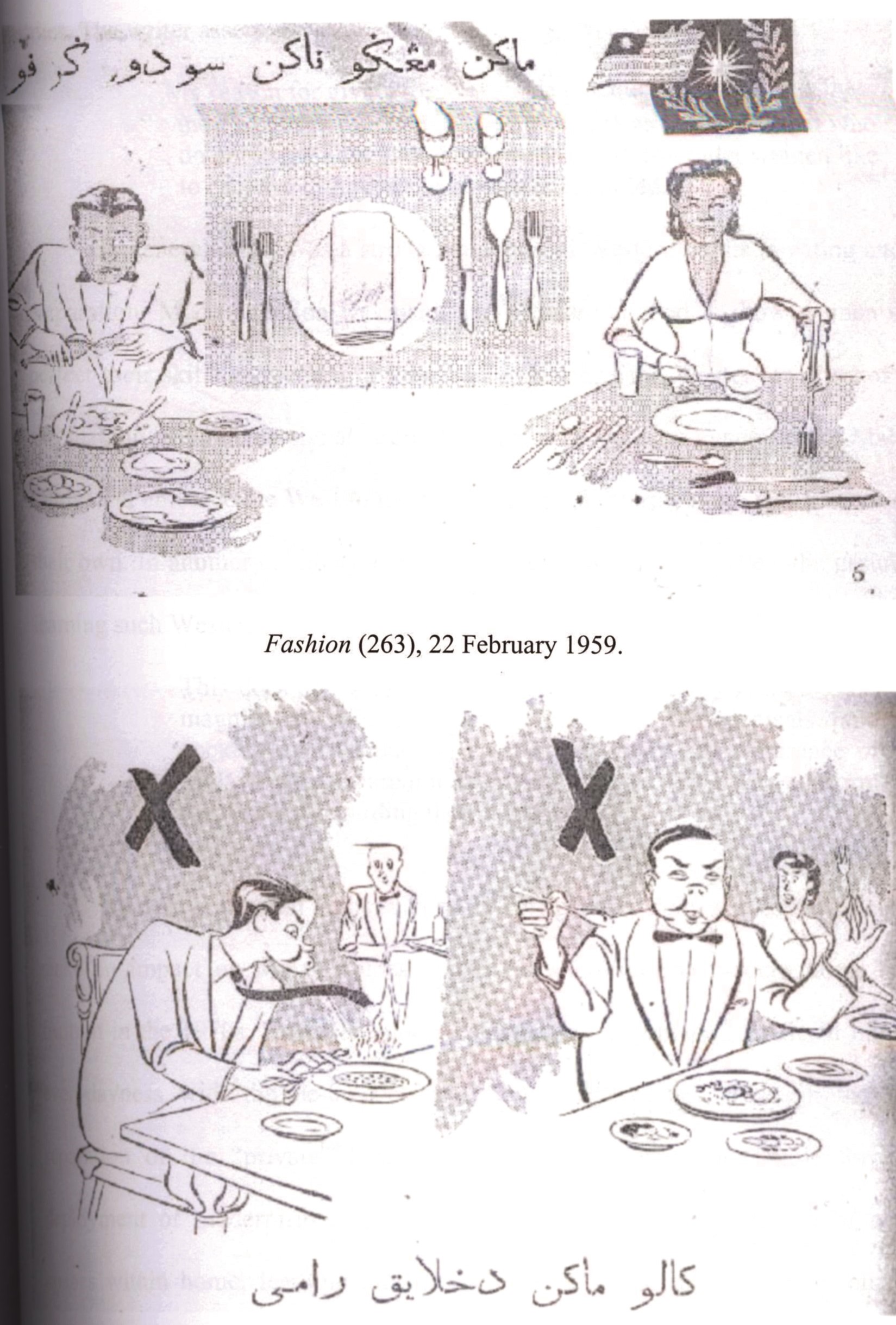

The latter were new to the Malay audience until the 1950s. Fashion is an example of a popular magazine which had a broad appeal, catering not only to women who are students or teachers but Malay women of all classes. Hamedi, however, does not identify Fashion as a women’s magazine despite it being listed in his directory.12 It was also not classified under any other genres.

Abdul Aziz notes that Fashion (produced by Harmy Press) and Mastika (Utusan Melayu Press) had more than 10,000 copies each per issue.13 (This did not take into account the frequency of printing and it was common for reprints due to high demand.) Other fictional and nonfictional titles (periodicals or books) issued only 5,000 copies per print. While Fashion was a weekly periodical, Mastika was a monthly literary periodical. This meant that Fashion would have a monthly production of at least 40,000 copies per print, whereas Mastika would have a monthly production of 10,000 copies per print. This testifies to the popularity of Fashion as a popular women’s magazine.

First published in June 1953, Fashion was the first magazine in Malaya to promote modern manners and dress among Malay women. It lasted 15 years. During this time, it was an agent of change for the development of the modern Malay woman. It provided information on areas of cooking, childcare, sewing as well as care for the home. My study on the invention of the modern Malay woman sheds more light on this.14

Men’s Magazines in the 1930s and 1950s

Men dominated the reading culture before the print of women periodicals in the mid-1930s. Given that most print materials were meant for men, would these automatically classify them as men’s magazines? How would we define men’s magazine then? For the purpose of this article, we define men’s magazines to be those which do not only have a primarily male readership but which persuades men to a certain lifestyle and that reflects the men’s standing, class or values. For the Malay men’s magazine, this may lean towards consumerism, but it may not be necessarily so. This is because consumerism within these magazines is reflected as a feminine virtue rather than a male trait.

Although modern scholars like Aziz and Hamedi did not consider men’s magazines to be a genre that existed before the war, men’s magazines had evolved much like the women’s magazines described earlier. As a genre, however, men’s magazines were not established like the women’s magazines. Therefore, their existence has not been examined and discussed in an elaborate study like Hamedi’s.

Men’s magazines before the war were characterised by their religious or nationalistic orientations and their didactic nature. Magazine titles such as Lidah Teruna (Johor, June 1920), Medan Laki-Laki (Singapore, 27 September 1935) and Majalah Pemuda (Johor, Novermber 1935) are worthy of mention as their names signalled that these magazines were meant for men. However, the magazines did not exclude women as there were columns for women, or columns dedicated to the discourse of women in Islam. The men’s magazines, like the women’s magazines of the period, were similar to general, educational or religious magazines. They were not distinctive as “men’s magazines”.

An insignificant amount of provocative titles was published in the 1930s. This was the beginning of consumer “men’s magazines” that modern life was associated with. Suleiman Ahmad, on behalf of the Royal Publishing Company, was infamous for the production of such men’s magazines. Some of these titles were Shorga Dunia (March 1936), Dunia Sekarang (14 July 1934) and Melayu Muda (13 July 1936).

Shorga Dunia was understood to be a men’s magazine. Hamedi categorises Shorga Dunia (Earthly Heaven) as “entertainment for the young [hiburan untuk mudamudi]”. In the newspaper Tanah Melayu (April 1936), it was reported:

“Kanak-kanak dan perawan-perawan tidak

dibenarkan membaca akhbar ini kerana sesetengah

daripada perkataan-perkataan dan gambar-gambar

yang di dalamnya mendahsyatkan pemandangan

dan membangkitkan keinginan hawa nafsu dengan

sekejapnya” [children and young women are not

allowed to read this because half of the words and

photographs contain inside [this publication] are

destructive to the sight and arouses the

desire in an

instant]. 15

In another instance, the same daily reported

“…suatu akhbar yang luar biasa dan sengit sekali.

Kanak-kanak dan orang-orang perempuan tidak

dibenarkan membeli akhbar ini” [a periodical that is

extraordinary and very narrow. Children and women

are not allowed to buy these].16

This was a rare instance when women and children are excluded from reading men’s magazines and this was not the case for other publications. This preclusion characterises this magazine as an exclusively men’s magazine. While this type of men’s magazine did not find much acceptance in its time, it was beginning to garner a wider acceptance in the social world of the 1950s. It is interesting to note that Singapore was the birthplace of such magazines in the 1930s and later in the 1950s. Such publications aroused religious and moral sentiments from the community across the Causeway. Regardless of this, men’s magazines of the 1950s were still very popular.

The more popular men’s magazines in the 1950s were Aneka Warna, Asmara, Album Asmara and Album Bintang. Hamedi describes Album Bintang as a magazine for “entertainment and light sex [hiburan/seks ringan]”. Pustaka H.M. Ali published the annual edition of Bintang magazine which contained tabloids, pictures of movie stars and long commentaries. Its first print was in 1955 and its last in May 1959. In May 1957, 15,000 copies of the magazine were printed. Jimmy Asmara was the chief editor from 1956–57.17

Syed Omar Alsagof published Album Asmara on behalf of Geliga Publications Bureau (at 430 Orchard Road). This was a yearly edition for Asmara. Like Album Bintang, Album Asmara saw its inaugural print in 1955 and its final print in 1959. Hamedi described this as an entertainment magazine (hiburan). The magazine was published as it “was asked by readers to create a magazine that contain stories on films from a cinematic perspective [didesak oleh pembaca supaya melahirkan majalah yang mengandungi hal-hal perfileman ditinjau dari sudut perfileman]”. The basis of this magazine was to “create stories surrounding passion/love [dasar album kami ialah mengisahkan kejadian di sekitar asmara]”.18

Aneka Warna, like Album Asmara, was described as “entertainment and light sex”. Unlike the two yearly editions mentioned earlier, Aneka Warna was a monthly magazine. It was first published in October 1954 and saw its final print in November 1959. Qalam Press then replaced Aneka Warna with Pusparagam in May 1960.

Due to its popularity, Aneka Warna managed to save Qalam press from financial troubles. These financial troubles were incurred due to a political disagreement with Tengku Abdul Rahman. The editor, Al-Edrus (Syed Abdullah Abdul Hamid al-Edrus), also known by his pen name, Ahmad Lufti, reacted critically to the Tengku burning copies of Warta Masyarakat and Qalam in Johor Bahru (both his productions) by writing an angry piece in a December 1953 issue. He had to close his newspaper as a result. Aneka Warna saved Qalam Press. It lasted five years from October 1954 to November 1959. Ahmad Lufti was the writer of Kesatuan Islam (13 December 1945) and Mastika.

Asmara, another magazine of this genre, reinforced Aneka Warna as a men’s magazine in its description of Aneka Warna (November 1954):

“Lain daripada yang lain, dapat menghiburkan tuan-

tuan dan dapat memberi tauladan kepada tuan-

tuan. Tetapi ingat! Kanak-kanak dinasihatkan jangan

membacanya! Hanya untuk orang-orang dewasa

yang gemar mengambil masa lapang, menghiburkan

hati dengan bacaan-bacaan ringan…” [Different

[from the rest], able to entertain the men and able to

provide guidance to men. But remember! Children

are advised not to read it! These are for the adults

who love their leisure, to amuse themselves with

light reading…].19

What was noteworthy was that female readers of the 1950s were not forbidden to read this genre of men’s magazines. This was not the case for women in the 1930s, indicating a change in attitude towards what was permissible for women’s reading pleasure.

Conclusion

As it is not possible to discuss the above mentioned magazines in detail, we will summarise why the discourse in the magazines is worthy of mention. The discourse on manners, behaviour, masculinity and femininity in men’s magazines and that in women’s magazines should be viewed somewhat differently. Apart from magazines being read or perused for their entertainment value, male writers and publishers used this symbol of white beauty to exercise moral power, not just as representers of permissible female femininity in Islam but over themselves as well.

On almost all occasions, male protagonists in short stories of men’s magazines such as Asmara and Aneka Warna (these were men’s literary magazines), would be roused to a state of temptation but experienced spiritual realisation afterwards. In addition, the male characters would understand the meaning of conjugal bliss with love in marriage. These were the normal plots in the adult stories in these men’s magazines. As women were allowed to read men’s magazines of the period, there was equal emphasis on chastity in men’s magazines as well. Overall, this reinforced an attempt by the literati class to redefine the “modern” according to standards demarcated by the culture and religion of the Malay community. Above all, these anxieties projected on white beauty reflected their own anxieties about the colonial power or the emerging American power.

For women’s magazines, the utility of such “white” images was to exercise a moral power over Malay women. In Fashion, immediately before the proclamation of the Independence of Malaya on 31 August 1957 and significantly after, fewer images of white women were published, while concurrently representations of Malay women were an ubiquity to the gaze of the public. This heavy use of representations of white women in magazines in the 1950s was an attempt to exploit anticolonial feelings that existed then. As a certain representation of white women was used in stark contrast to one of Malay women on covers of magazines, this reinforced the idea of the “them” versus “us” discourse. Whether these were images of sexy Hollywood actresses or Miss Americas, which were in stark contrast to the full-sized images of Malay women, images were not without their ideologies. Bearing that in mind, the implications were provocative especially when Fashion was intended for the Malay society of Malaya and Singapore, whose religious inclinations placed an overriding emphasis on the modesty of women. Despite this, even with the insertion of such “raunchy” materials, it was reported that the weekly was a hit with them.

Interesting examples from periodicals reinforced the shared understanding by culture and intellectual historians as well as gender specialists that while we apply high standards to the task of interpretation in the historical enterprise, the same standards to the selection of historical written sources cannot be employed. This is significant when periodicals provide not only the mentality and worldviews of specific communities about themselves, but offer deeper insights to the anxieties they shared about other communities or groups they represent in these periodicals. Cultural historians are more willing to admit to the flaws in their cultural historicism than other historical scientists could or would in the “science” they practise. Taking measures to ensure important conclusions through high standards of interpretation remains for this field of historical inquiry.

Associate Librarian

Lee Kong Chian Reference Library

National Library

NOTES

-

Khoo Kay Kim, Majalah Dan Akhbar Melayu Sebagai Sumber Sejarah [Malay papers and periodicals as historical sources]. Bersama Dengan Satu Senarai Berkala-Berkala Melayu Sebelum Merdeka Dalam Pegangan Perpustakaan Universiti Malaya; Dan, Satu Bibliografi Mengenai Pengkajian Berkala Melayu [With a list of Premerdeka Malay periodicals held in the University of Malaya Library; and, A bibliography on the study of Malay periodicals] (Kuala Lumpur: Perpustakaan Universiti Malaya, 1984). (Call no. Malay RSEA 070.509595 KHO) ↩

-

A.M. Iskandar Ahmad, Persuratkhabaran Melayu, 1876–1968 (Kuala Lumpur: Dewan Bahasa dan Pustaka, Kementerian Pelajaran, Malaysia, 1980). (Call no. RCLOS 079.595 AMI-[SEA]) ↩

-

Kartini Saparudin, A Self More Refined: Representations of Women in the Malay Magazines of the 1950s and 1960s (Singapore: National University of Singapore, 2002). (Call no. RSING 305.42095957 KAR) ↩

-

Kartini Saparudin, “Colonisation of Everyday Life” in the 1950s and 1960s: Towards the Malayan Dream” (Master’s thesis, National University of Singapore, 2005). ↩

-

Benedict Anderson, Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism (New York: Verso, 1983), 49. (Call no. RU 320.54 AND) ↩

-

Tim Harper, The End of Empire and the Making of Malaya (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999), 274. (Call no. RSING 959.5105 HAR) ↩

-

Kristin Ross, Fast Cars, Clean Bodies: Decolonization and the Reordering of French Culture (Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 1995), 77–78. ↩

-

William R. Roff, Bibliography of Malay and Arabic Periodicals Published in the Straits Settlements and Peninsular Malay States 1876–1941; With an Annotated Union List of Holdings in Malaysia, Singapore and the United Kingdom (London: Oxford University Press, 1972). (Call no. RCLOS 016.0599923 ROF) ↩

-

Ian Proudfoot, The Print Threshold in Malaysia (Australia: Centre of Southeast Asian Studies, Monash University, 1994). (Call no. RSEA 070.509595 PRO) ↩

-

Hamedi Mohd. Adnan, Direktori Majalah-Majalah Melayu Sebelum Merdeka (Kuala Lumpur: Penerbit Universiti Malaya, 2002). (Call no. Malay R 059.9928 HAM) ↩

-

Ahmad, Persuratkhabaran Melayu. ↩

-

Hamedi, Direktori Majalah-Majalah Melayu, 233. ↩

-

Abdul Aziz Hussain, “Penerbitan Buku-Buku Dan Majalahmajalah Melayu Di Singapura Di Antara Bulan Sept 1945 Dengan Bulan Sept 1959,” (Latihan Ilmiah, Universiti Malaya Singapura, 1959) ↩

-

Saparudin, A Self More Refined. ↩

-

Hamedi, Direktori Majalah-Majalah Melayu, 129. ↩

-

Hamedi, Direktori Majalah-Majalah Melayu. ↩

-

Hamedi, Direktori Majalah-Majalah Melayu, 129. ↩

-

Hamedi, Direktori Majalah-Majalah Melayu, 250. ↩

-

Hamedi, Direktori Majalah-Majalah Melayu, 246. ↩