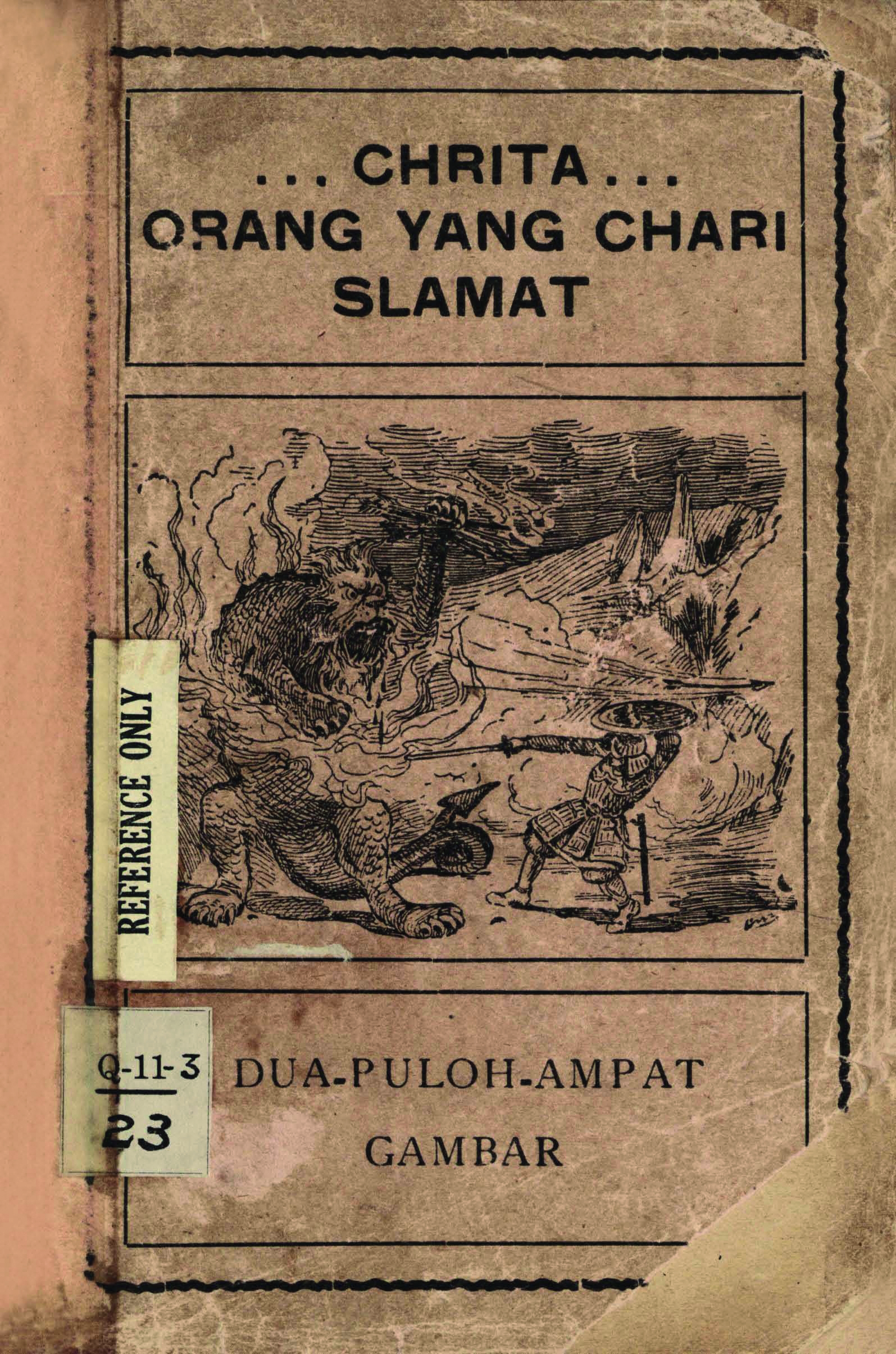

A Graphic Tale in Baba Malay: Chrita Orang Yang Chari Slamat (1905)

Senior Librarian Bonny Tan shines the spotlight on Chrita Orang Yang Chari Slamat, the Baba Malay translation of the classic, The Pilgrim’s Progress.

Introduction

Before J.R.R. Tolkien there was John Bunyan. Pilgrim’s Progress was a 17th-century bestseller based on an allegorical world of the Christian faith’s journey.

Bunyan was an unschooled thinker from an impoverished family who was inspired by his faith to share the gospel with others. While imprisoned for conducting religious service outside the official church, Bunyan penned the now immortal Pilgrim’s Progress. First published in 1678, it traces the journey of Christian, the everyman of faith, from the City of Destruction to the Celestial City.

Caricatures representing spiritual encounters and transformation, culled from Biblical parables and various scriptural references, show that the adventure could very well have been Bunyan’s own spiritual autobiography. Bunyan conveyed the convert’s life of faith so simply yet vividly through the allegorical sojourn that it soon became a bestseller in England. It was then carried beyond the English shore by missionaries who fanned out to the outposts of the colonised world.

The book has been translated into more than 200 languages, was never out of print and remains one of the most widely read today.

Almost 250 years since its first publication, another passionate Christian in Malaya translated this classic into Baba Malay. He was none other than soldier, scholar and missionary William Shellabear.

Malay Translations

The story of the Pilgrim was already much alive among the local community at the turn of the 20th century. For instance, in the 1880s, readings from Pilgrim’s Progress in Chinese were conducted at the Prinsep Street Church for Straits Chinese, accompanied by singing in English and Malay concerning the life and works of Bunyan and illustrated using magic-lantern slides.1 Characters such as Worldly Wiseman and Hopeful were thus part of the Christian vocabulary among the Straits Chinese prior to the publication of the story in Baba Malay.

In the Malay Archipelago, the tale had had several translations and versions. One of the earliest translations was done in Jawi some time in the 1880s; it was then followed by a Dutch romanised Malay version. In the Malay Peninsula, Benjamin Keasberry, a missionary serving under the London Missionary Society and father of Malaya’s early printing press, brought out one of the first Malay versions.

Shellabear’s translation however was unique in the Malay Peninsula as it was in Baba Malay and published especially for the Straits Chinese community. Shellabear makes reference to one of these earlier publications and his reasons for publishing a version for the Straits Chinese in the introduction to his book:

“Ada brapa puloh tahun dhulu satu tuan yang pandai skali sudah pindahkan ini chrita dalam bhasa orang Mlayu: ttapi sbab dia pakai perkata’an yang dalam-dalam, terlampon susah orang China peranakan mngerti, dan sbab itu kita bharu pindahkan ini chrita dalam bhasa Mlayu peranakan, spaya smoa orang China dan nonya-nonya yang chakap Mlayu boleh mngerti baik baik.”

(“Several decades ago, an intelligent gentleman translated this tale to Malay. However, as he used complex terms, the Chinese Peranakans found it difficult to understand. Because of this, we have translated this tale into Peranakan Malay so all Chinese and their women folk who speak Malay will be able to better understand it.”)

Slightly more than a decade after Keasberry passed away, Shellabear came to Singapore in 1887, not as a missionary but as a military man in the British Royal Engineers, assigned to build Singapore’s defence. He fell in love with the Malay soldiers under his command and sought to take the gospel story to them. Thus his passion turned him to translating religious works into Malay and, conversely, translating Malay classical mythology into English. Leaving the military, he joined the Methodist Missions and established the Methodist Mission Press in Singapore which brought out various publications in Malay along with invaluable language tools such as English-Malay dictionaries and grammars, which are still highly regarded even today.

The press and his translation work took much of his time, but Shellabear had to return to England in 1894 on account of his wife Fanny’s ill health. She unfortunately passed away and Shellabear returned to Singapore and later married Emma Ferris in 1897, an active Methodist missionary whose work had crossed paths with his. By 1904, the Shellabears’ base for missionary work had moved to Malacca, the heartland of the Straits Chinese. It was here that Shellabear would translate Pilgrim’s Progress.

The Use of Baba Malay

Shellabear had already made the acquaintance of the unique hybrid community of Chinese in Singapore, many of whom traced their genealogy to the Malaccan Straits Chinese. This included prominent community member, Tan Keong Keng, who was one of the early Straits Chinese to adopt the thoroughly Western idea of having his daughters educated.2 Thus he persuaded the Shellabears to establish a school for girls in Malacca. Tan’s home at Heeren Street in Malacca was given to Emma Shellabear and Ada Pugh to start the institution – a task most suited to Shellabear’s wife Emma who had already been active in the Methodist girls’ school in Singapore.

Meanwhile, Tan sent his only son, Tan Cheng Poh, to Shellabear to learn how to type and practise English. With little to translate to English, Emma considered having him translate a children’s version of Pilgrim’s Progress into Baba Malay instead. The exercise was Shellabear’s first introduction to Baba Malay and he became fascinated with its “distinct dialect of Malay, with very definite idioms and rules of its own”.3 Another Baba, Chin Cheng Yong, was recruited to help in verifying the accuracy of the translation; but little is known of him.

In translating Pilgrim’s Progress, Shellabear kept close to the original text, including scriptural references which Bunyan had noted. He was careful to keep his translated language simple and clear: “Skali-kali kita t’ada pakai perkata’an yang dalam-dalam atau yang orang susah mngerti, mlainkan dalami agama punya perkara ada juga sdikit perkata’an yang orang t’ada pakai s-hari-hari…” (“Thus we have refrained from using complex terms or those people find too difficult to understand, except for that pertaining to religious terms which may not be frequently used by most…”)

Particularly challenging were the translations of the book’s place names as many are abstract terms with peculiar Christian connotations. Shellabear had used an older Malay edition of the story, lithographed in Munshi Abdullah’s Jawi script, to help determine the translations of the various characters.4 Thus most of the terms were translated into more formal Malay terms or, if not, were taken directly from the English or Christian terms. For example, Christian’s name is literally translated as “Kristian”, while “Beulah Land” is transcribed as “Tanah Biulah”. The title of the book Pilgrim’s Progress has cleverly been simplified to Orang Yang Chari Slamat (“One Who Seeks Salvation”), although this title could have been Keasberry’s original translation or that of the earlier versions in Malay.5 To assist his readers in grasping the meanings of these terms, the appendix lists all the given place names and personal names with both Baba Malay and English translations along with page references. This is followed by a glossary of terms with both a Peranakan explanation and an English translation. Some terms include definitions according to Malay terms. For example, “gombala” is explained in Malay as “gumol” or “wrestle”.

More interestingly, Shellabear expressed the need to include in the glossary English terms because he expected many of his readers to be proficient in English: “Lagi pun dalam ini chrita ada banyak nama orang dan nama tmpat yang kita sudah kumpolkan, dan sudah taroh Inggris-nya yang John Bunyan sudah pakai, spaya orang yang tahu bhasa Inggris boleh bandingkan dan boleh mngerti lagi baik…” (“Also, in this tale, many personal pronouns and place names we have compiled with English terms that John Bunyan himself used so those who understand English can compare and better understand…”).

However, the grammar of the text conveys some of the unique nuances inherent in Baba Malay, mainly influenced by Hokkien linguistic constructs. For example, this sentence found in the introduction is full of the idiomatic phrases peculiar to Baba Malay: “Ttapi John Bunyan ta’mau ikut itu ong ke kau punya smbahyang, dan sbab itu bila dia ajar dalam dia punya greja dia kna tangkap, dan dia kna tutop dalam jel….”6 (“However, John Bunyan did not want to follow the religious practices of the official church and so, when he taught at his own religious gathering he was caught and placed in jail….”). “Punya”, a Malay term meaning “to own” is used instead as the Hokkien possessive particle “e”, a common construct found in Baba Malay, is unknown in vernacular Malay. In the same vein, “kena” is also used to convey passive past – “dia kena tangkap”. “Ong ke kau” is a Hokkien idiomatic term which Shellabear explained in the previous sentence as “Kompani punya greja” (The company’s church). “Jel” is also a transliteration from the English “jail”. Thus, as is typical of the Baba language, the text has a mix of Malay, Hokkien and English terms.

However, it is only in the introduction to the text that Shellabear remains true to Baba Malay. In the translation of the story, a more proper though low Malay is applied. Thus, although key terms such as “punya” are consistently applied, other typical terms such as “gua” for the personal pronoun “I” and “lu” for “you” are not used. Instead, Shellabear applies the Malay terms “sahya” (“saya” or “I”) and “angkau” (“engkau” or “you”).7 That Shellabear retained the more “proper” Malay expressions and terms in the translation may mean that he wanted a wider audience for the book and showed his higher regard for the use of standard Malay.

Illustrations of the Straits Chinese

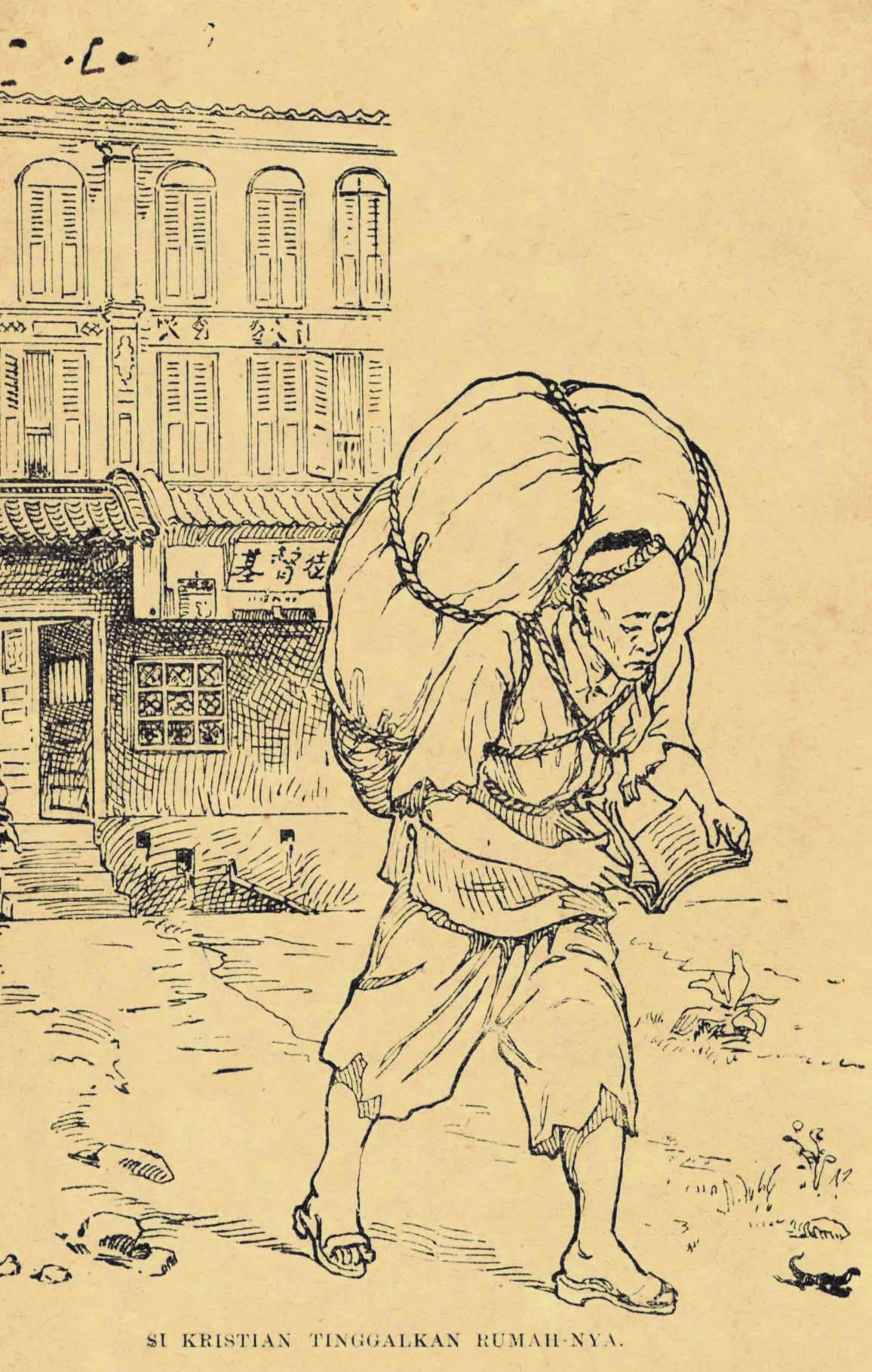

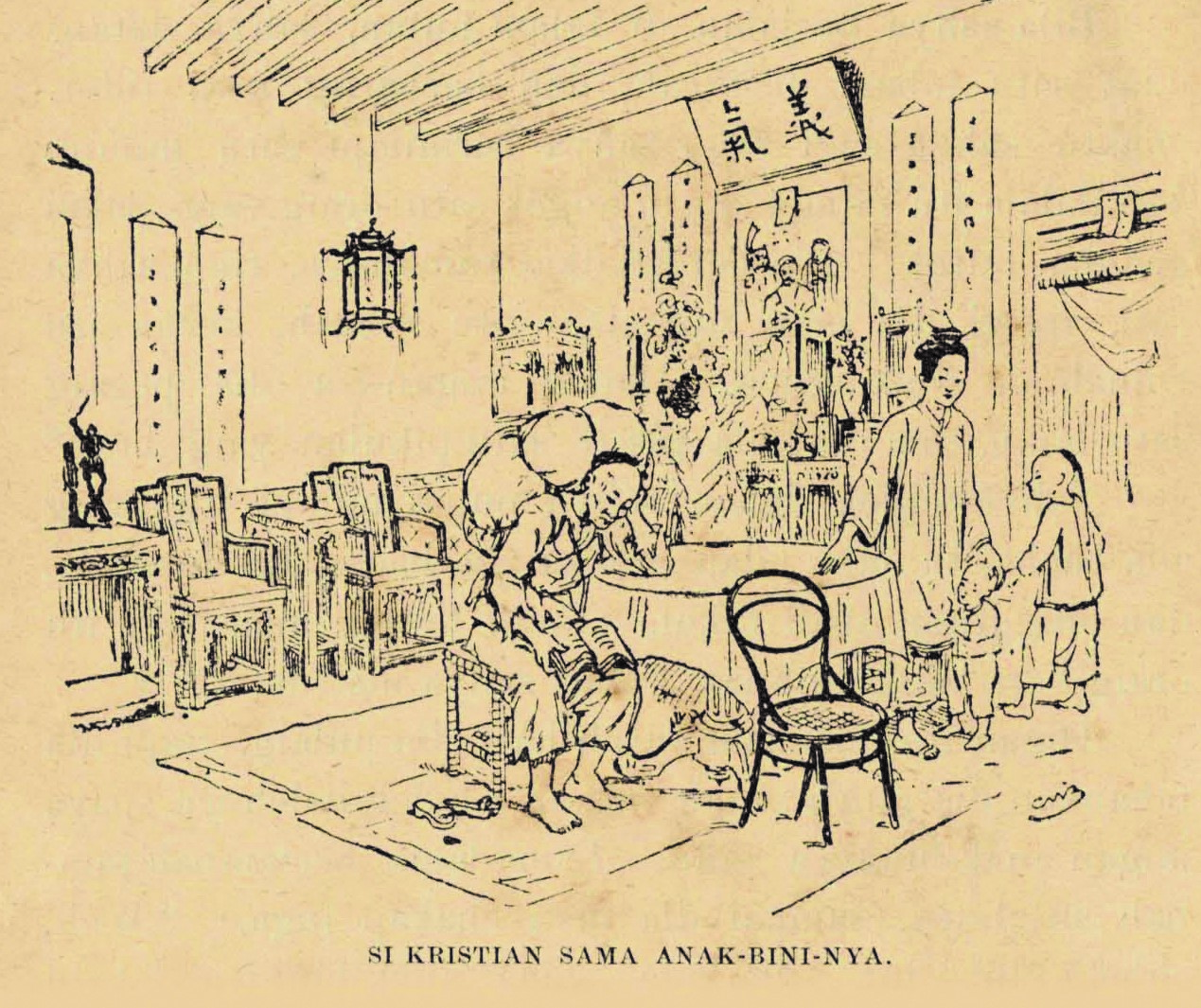

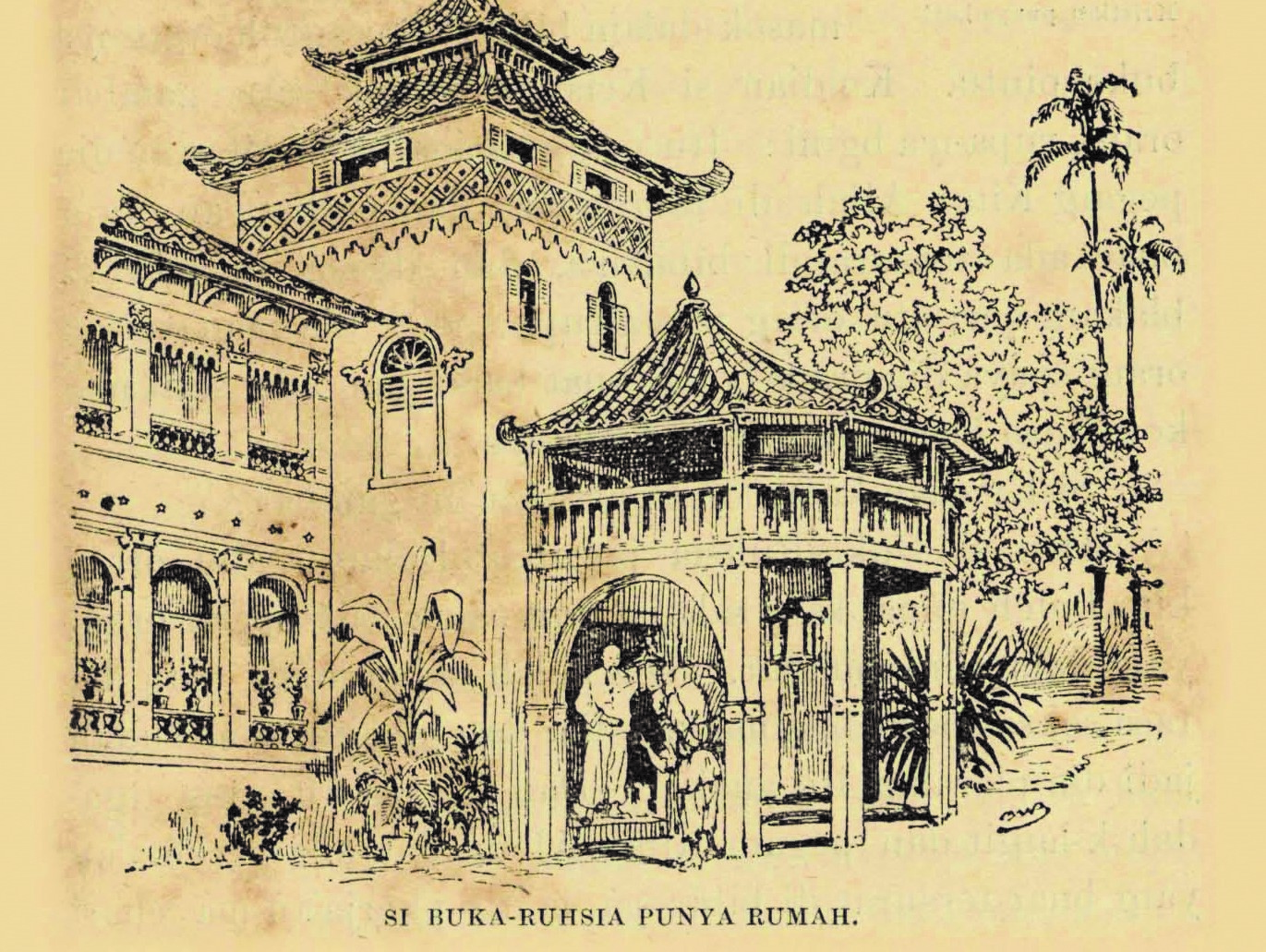

T.W. Cherry had taken over from Shellabear in the running of the Methodist printing press in Singapore. In mid-1904, C.W. Bradley, a young illustrator, had been sent by the American Methodist Missions to assist Cherry in the work of the printing press. Unfortunately, Bradley proved inadequate in printing duties as his only experience had been as a cartoonist for a newspaper. As the Missions had to pay for his passage home, he was sent to Shellabear in Malacca to illustrate Pilgrim’s Progress to make it worth their money.8 The result was 24 fine-line drawings that detail the life of the Chinese in the Straits Settlements at the turn of the 20th century.

In the introduction, Shellabear praised Bradley for his accurate depiction of the local people and scenery: “dia sudah tulis btul sperti rupa orang dan rumah-rumah dan pokok-pokok yang kita tengok sini s-hari-hari” (“he has made realistic drawings of people, homes and trees that we see daily”).

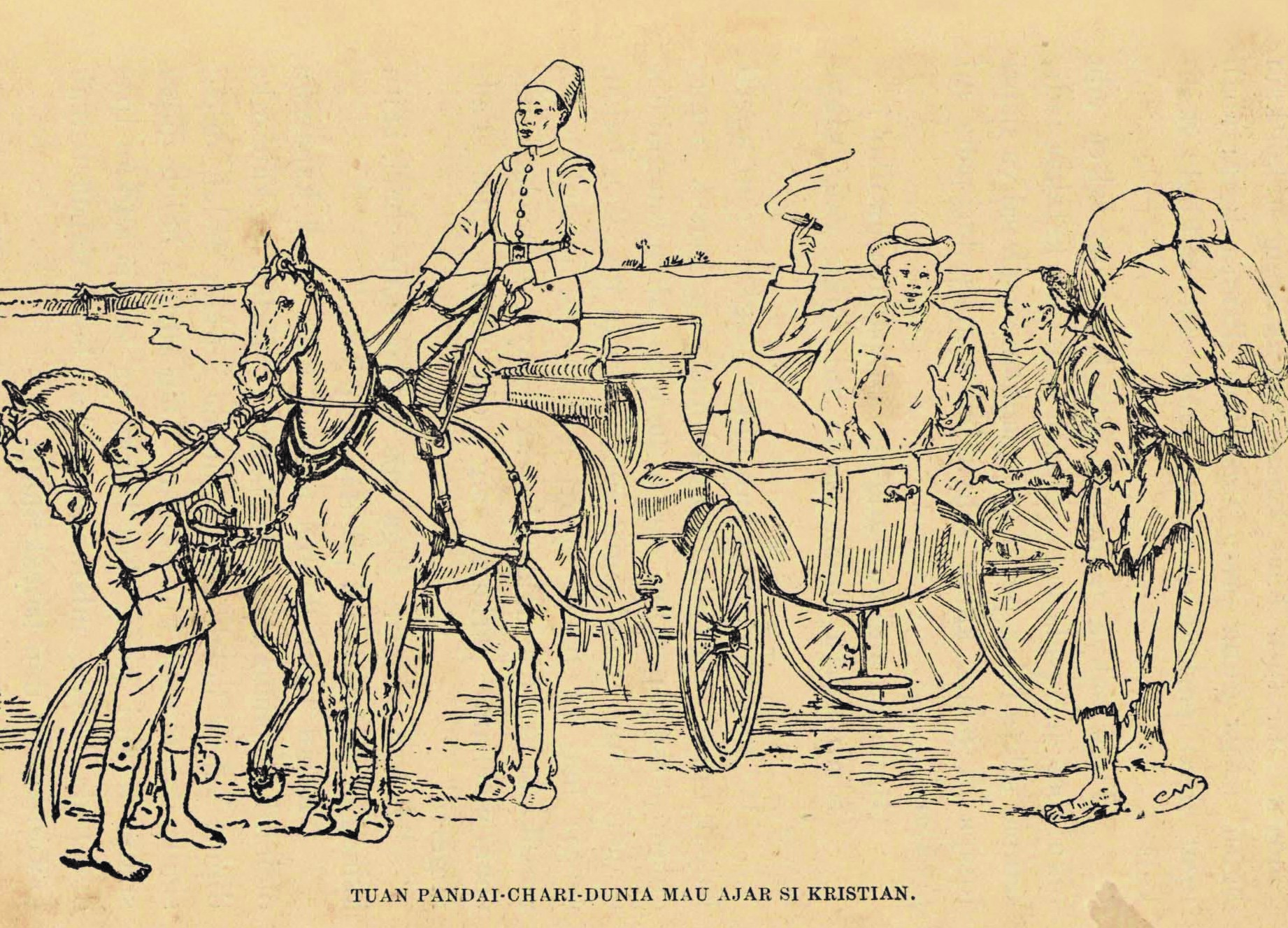

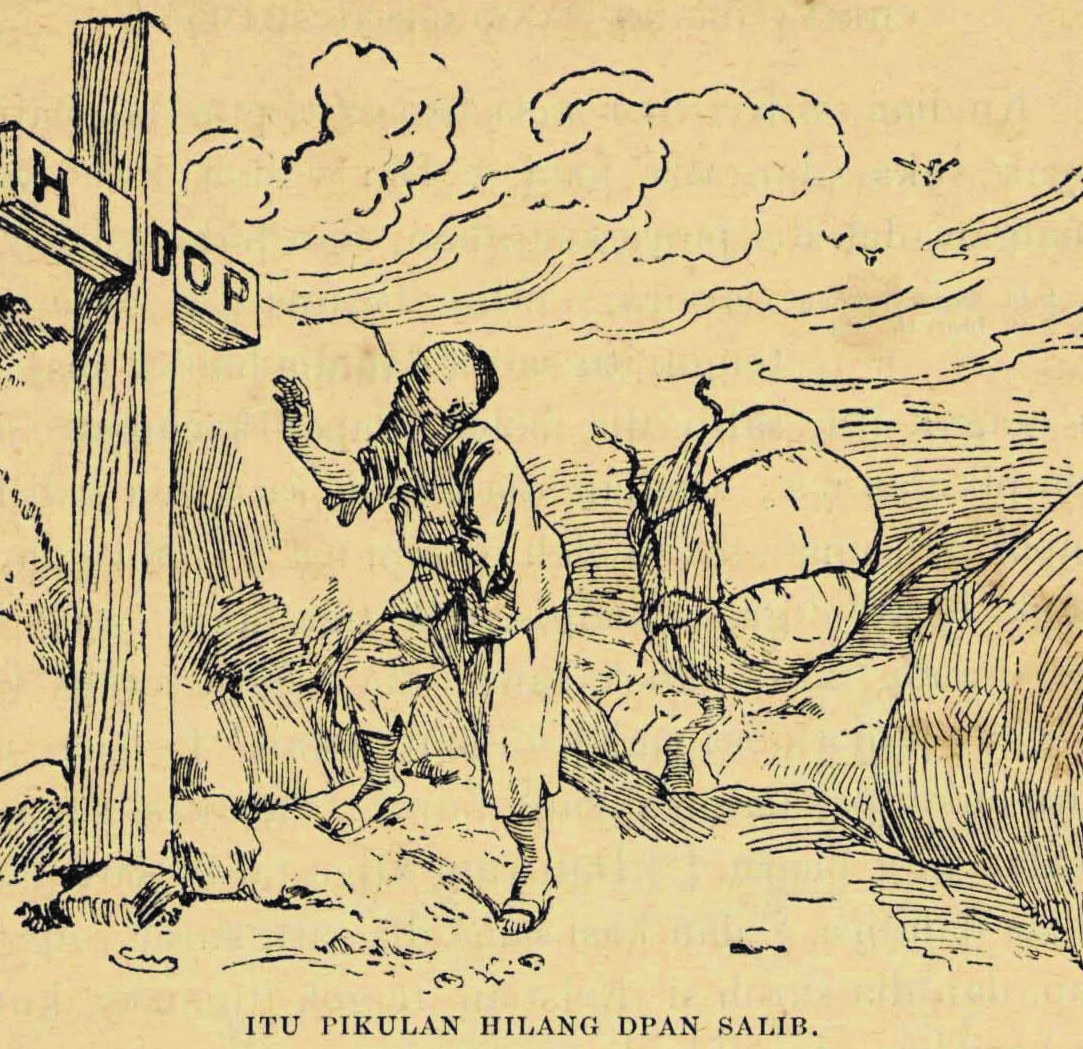

Indeed, the background scenes in the illustrations include coconut trees and banana clumps typically found in tropical Malaya. The familiar facades of the Malayan shop house and its interiors are also sketched. However, it is noteworthy that Si Kristian (Christian) is depicted as a typical Qing Chinese, complete with queue and Chinese clogs. However, when he encounters Tuan Pandai-chari-dunia (Mr Worldly-wise), the wealthy man rides a modern horse-drawn carriage driven by what appears to be young barefoot Malays wearing Turkish hats. The wealthy Chinese dons a mix of oriental and modern Western clothes topped with an English hat. Interestingly, Si Kristian acquires these Western trappings – a top hat and shoes – soon after his burden of sin falls away at the foot of the cross. It is uncertain if the Western costumes represent the Baba dress at the turn of the century since many of the drawings seem mainly of generic Chinese that had come to Malaya. Nonyas in kebayas and Babas of yore in their hybridised costumes are not really reflected in Bradley’s illustrations.

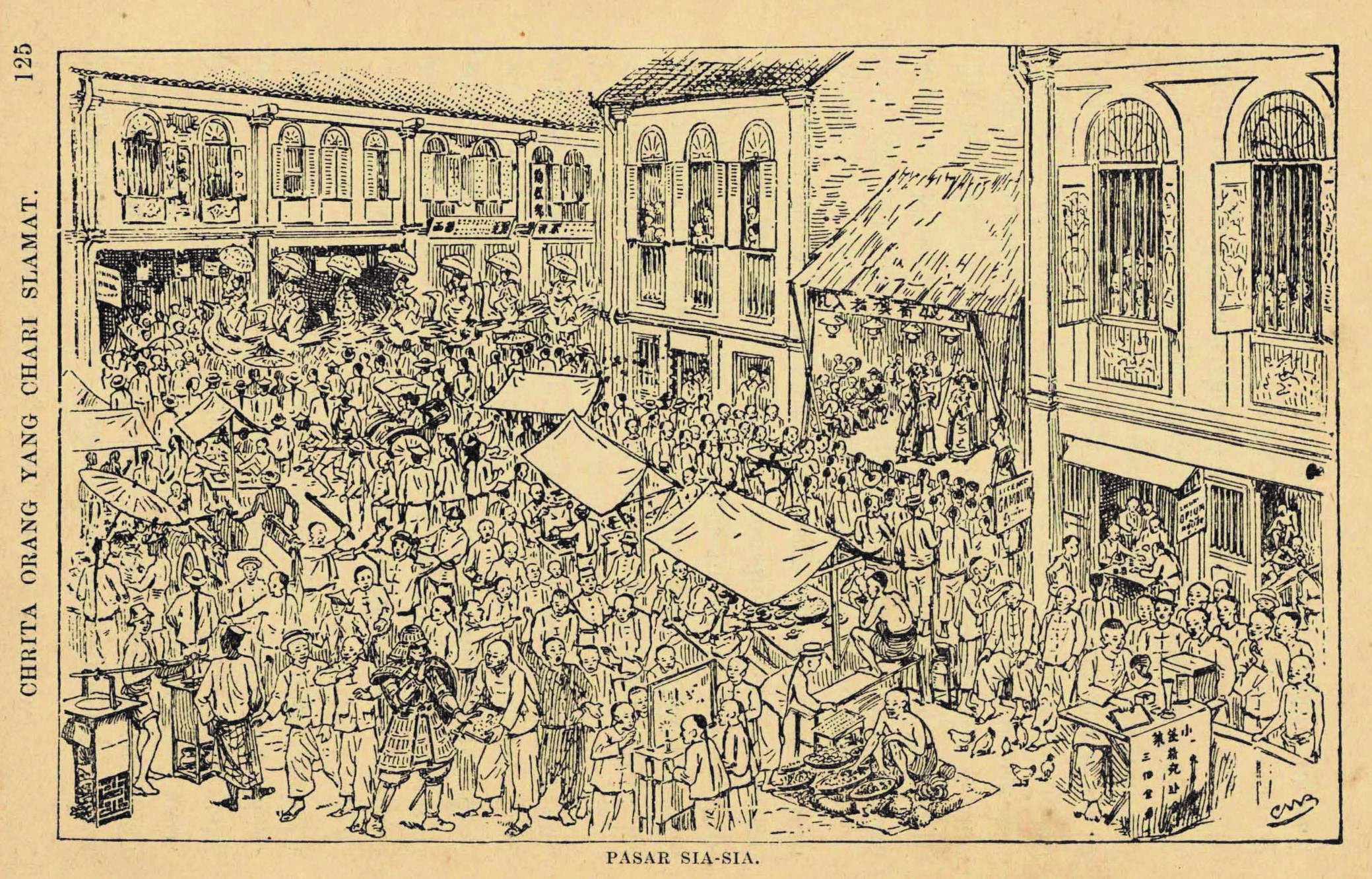

At Pasar Sia Sia (Vanity Fair), a detailed scene of the local Chinese congregating at a marketplace, shows a vignette of the 20th century Malayan Chinese community in its complex social world. Many were likely part of the influx of immigrants who had journeyed from China since the 1880s. In fact, Singapore’s Chinese population had almost doubled from 87,0000 in 1881 to 164,0000 by the 1900s.9

On the extreme right of the picture is a tea house located in a typical Straits Chinese house. Beside it, a letter writer reads a letter while a crowd of patrons await his services. Scenes from the wet market show vegetables sold on the dirt floor while chicks roam at the feet of men having their hair cleaned of lice, all showing Bradley’s keen eye for detail. At the foot of a wayang performance are food stalls where Chinese men eat while squatting on their chairs. Among the sea of fair-skinned men are a few Malays and turbaned Indians.

The shophouses with tiled sloping roofs, wooden shutters and animal figures in plaster below the windows are those found in the Straits Settlements. Other drawings give details of the interiors of Chinese mansions and, in contrast, the humble home of Si Kristian. They do not necessarily show the Malayan features or cosmopolitan designs which now have become associated with Peranakans. In fact, much of the interiors are of Chinese taste. Nevertheless, the graphic details of Bradley’s illustrations are invaluable for the study of the social lives of the local Chinese in the early 20th century.

Shellabear’s Celestial City

The publication was released in November 1905 and, by 1913, Shellabear had published the New Testament – Kitab Perjanjian Bahru – in Baba Malay, along with an article on Baba Malay in the Journal of the Malayan Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society. Although he remained a premier scholar of Malay text and focused mainly on publishing in Malay, these Baba publications testify to Shellabear’s versatility and interest in the wider local community.

By 1917, however, translation work and ministry took its toll on Shellabear and he returned to the United States on furlough. Even though he attempted a return to the East, health and internal politics lead him to retire from missionary work by 1919. Yet he never left his love for the Malays and Malay works, mastering Arabic later in life and then teaching and writing about the Malays while at the School of Missions at Drew University.

The story does not end here. In 1955, eight years after Shellabear’s death, his son-in-law R.A. Blasdell continued the family tradition and published a higher Malay version of Pilgrim’s Progress as Cherita Darihal Orang Yang Menchari Selamat (1955) (“The Story of One Seeking Salvation”).

Chrita Orang Yang Chari Slamat is part of the Rare Book Collection in the National Library Singapore. It has been digitised and can be found online at National Library Online or at the Lee Kong Chian Reference Library on microfilm NL8790.

The author wishes to acknowledge the invaluable help of Dr Robert Hunt who pointed to details of Shellabear’s life and publications and provided access to unpublished materials.

Senior Librarian

Lee Kong Chian Reference Library

National Library

REFERENCES

Anak Singapura, “Notes of the Day,” Straits Times, 12 December 1934, 10. (From NewspaperSG)

C.M. Turnbull, A History of Singapore, 1819–1988 (Singapore: Oxford University Press, 1989). (Call no. RSING 959.57 TUR)

John Bunyan, Chrita Orang Yang Chari Slamat (Singapore: American Mission Press, 1905). (From BookSG; call no. Malay RRARE 823.4 BUN; microfilm NL8790)

Robert Hunt, “The Life of William Shellabear,” Journal of the Malayan Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society 66, no. 2 (1993): 37–72. (From JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website)

Robert Hunt, William Shellabear: A Biography (Kuala Lumpur: University of Malaya Press, 1996). (Call no. RSING 266.0095957 HUN)

“Untitled,” Straits Times, 11 July 1887, 2. (From NewspaperSG)

W.G. Shellabear, “Baba Malay: An Introduction to the Language of the Straits-Born Chinese,” Journal of the Straits Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society no. 65 (December 1913): 49–63. (From JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website)

W.G. Shellabear, The Life of the Reverend W. G. Shellabear, DD, ed. and annotated Robert Hunt. (Unpublished)

NOTES

-

“Untitled,” Straits Times, 11 July 1887, 2. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Song, 529. ↩

-

W.G. Shellabear, The Life of the Reverend W. G. Shellabear, DD, ed. and annotated Robert Hunt, 37. ↩

-

Shellabear, Reverend W. G. Shellabear, 37. ↩

-

I was unable to find the translation by Keasberry or the earlier Javanese translations. ↩

-

W.G. Shellabear, “Baba Malay: An Introduction to the Language of the Straits-Born Chinese,” Journal of the Straits Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society no. 65 (December 1913): 49–63. (From JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website); John Bunyan, Chrita Orang Yang Chari Slamat (Singapore: American Mission Press, 1905). (From BookSG; call no. Malay RRARE 823.4 BUN; microfilm NL8790) ↩

-

Shellabear was well aware of the use of these Hokkien terms and actually explained the different usage in both Baba Malay and vernacular Malay in his article Shellabear, “Baba Malay.” ↩

-

Shellabear, Reverend W. G. Shellabear, 37. ↩

-

C.M. Turnbull, A History of Singapore, 1819–1988 (Singapore: Oxford University Press, 1989), 95. (Call no. RSING 959.57 TUR) ↩