European Perceptions of Malacca in the Early Modern Period

A major site of intra-Asia trade between India and China, Malacca was also an important site in European expansion into Asia. Lee Kong Chian Research Fellow Katrina Gulliver examines the importance of Malacca to Europe, and how the city developed with European influence.

Malacca was controlled by European powers for more than 400 years – by the Portuguese in 1511, the Dutch in 1641, and the British, first temporarily in 1795, then from 1824 as part of the Anglo-Dutch Treaty, in which the city was exchanged for Bengkulu in Sumatra.

Malacca held an important role in the European expansionist imagination. Tomé Pires said: “Whoever is lord of Malacca has his hand on the throat of Venice.” English texts from the 16th century onwards demonstrate a desire to capture the port, and the cultural position its name held as a symbol of wealth and the exotic. This paper looks at how Malacca was used, and how it demonstrates changing attitudes towards colonisation and the idea of the city.

Malacca was an important site in European expansion into Asia. In the 15th century, the city was a crucial nexus of a trade network from the Moluccas to Venice. Being at the “end of the monsoon”, it served as a major site for intra-Asia trade between China and India. I have chosen to look at the city from a different angle, in examining how important Malacca was to Europe, and how the city developed with European influence.

European Perceptions of the City

The term Golden Khersonese (or Chersonese) appears in Ptolemy’s geography, referring to what was later confirmed to be the Malay Peninsula.1 This term was in use during the early modern period in Europe to refer more specifically to the region, and in a more vague, mythical sense as a site of treasure. During the late 15th century, the city of Malacca came to be known in Europe, and references to it began to appear in literature.

During Portuguese control of the city, the references became more common, both in factual references and literature. I am limiting my references to printed works that would have been available to a broader audience than unpublished manuscripts. Gasparo Balbi’s Viaggio dell’Indie Orientali, published in Venice in 1590, described Malacca’s location and what could be bought there (sandoli, pocellane: sandalwood and porcelain, p. 64), and detailed the dates of the monsoon season between Goa and Malacca.2

The overlap in usage between Malacca and Golden Chersonese is discussed in this 1604 text:

The “great & famous illand” description also demonstrates a growing level of assumed knowledge in Europe about the East Indies, and how much they had even by this stage (the English East India Company’s first mission was in 1601) become part of the mental map projected from Europe.

A more detailed description of Malacca was given by Pierre d’Avity, translated into English in 1615:

Here we see two elements emerging in the description: One is the wealth and success of the town, and the other its position as a central gathering place for traders from different regions, as what might be termed proto-multiculturalism.

In Portuguese literature (the city is mentioned in the Lusiad of 1572, an epic poem by Luís Vaz de Camões, depicting Portuguese history and the events of the discovery of India as blessed by mythological figures) demonstrating even at this stage its role – and that of colonialism in general – in Portuguese national culture.

Malacca is mentioned in Book X, verse 44:

Nor Him shalt Thou (though potent) scape, and flye,

(Though sheltred in the Bosome of the Morn)

MALACCA (and the Apple of her Eye)

Prowd of thy wealthy Dow’r as her first-born.

Thy poyson’d Arrows, those Auxiliary

CRYSES I see (thy Pay That do not scorn)

MALACCANS amorous, valiant JAVANS,

Shall all obey the LUSITANIANS.

And verse 57:

Great Actions in the Kingdom of BINTAN

Thou shalt perform, MALACCA’S Foe: her score

Of Ills in one day paying, which That ran

Into, for many a hundred year before.

With patient courage, more then of a man,

Dangers, and Toyles, sharp Spikes, Hills always hoare,

Spears, Arrows, Trenches, Bulwarks, Fire and Sword,

That thou shalt break, and quell, I pass my word.

(This text is from Richard Fanshawe’s 1655 translation; the work has been translated a number of times into English.)

By the 17th century, Malacca was making a more regular appearance in literature written in English. As well as its inclusion in guides of the world, guides to spices and general histories, it was again featured in poetry. David Dickson was a Scottish preacher and his Truth’s Victory over Error, or, An abridgement of the chief controversies in religion which since the apostles days to this time, have been, and are in agitation, between those of the Orthodox faith, and all adversaries whatsoever… was a translation into English of Dickson’s sermons given in Latin. It is relevant that by this stage the city of Malacca was being specified rather than the more vague “Golden Cherson”.

“As Ophirs Gold, which from Malacca came,

Made Solomon on Earth the richest Man.

So will this Book make rich thy heart and mind,

With Divine Wisdom, Knowledge of all kind.

Thee richer make than Croesus of great name,

Thee wiser make than Solon of great fame.

Than all the seven wise Sages, Greeces Glory,

I do protest it’s true, and is no Story.”3

We also see the direct Biblical link being used. Malacca was being firmly situated in the cultural geography of Europe in texts such as this. Being already “familiar” and linked to Biblical and classical references, the city developed an identity in European culture through these depictions. This also links to the Portuguese use of religious justification for colonisation.

Under the heading “Manners of the People”, the residents were described by Pierre d’ Avity as follows:

He draws a clear distinction between the Christian Portuguese residents and the local community. The exoticism of the Malays in this description, as both murderers and passionate authors of romantic songs and poems is an interesting juxtaposition. It is particularly relevant that the Malays, or “they that are borne in this place” are not described as Muslims.

Influencing the City

There are two major themes in colonial historiography that are often applied to city sites: one is that colonisers took the opportunity to create “ideal” cities, often based on the Renaissance vision of the perfect city with straight streets and boulevards and a central square marked by visual symmetry and balance. The idea of building the ideal city from scratch was appealing because it was something that could not be done in Europe where most of the cities had developed organically over hundreds of years without central planning. These neoclassical ideas were brought in to, for instance, city planning by the Spanish in the Americas. It was also seen in some of the towns built by the British in India, which were built to appeal to an aesthetic of Oriental classicism, rather than resembling architecture in Britain.

The second approach to colonial cities is a presumed intention of replication of the metropolis. More than simply utilising known construction techniques and plans, this vision is aimed at recreating the experience of living in Europe.

Under the Portuguese

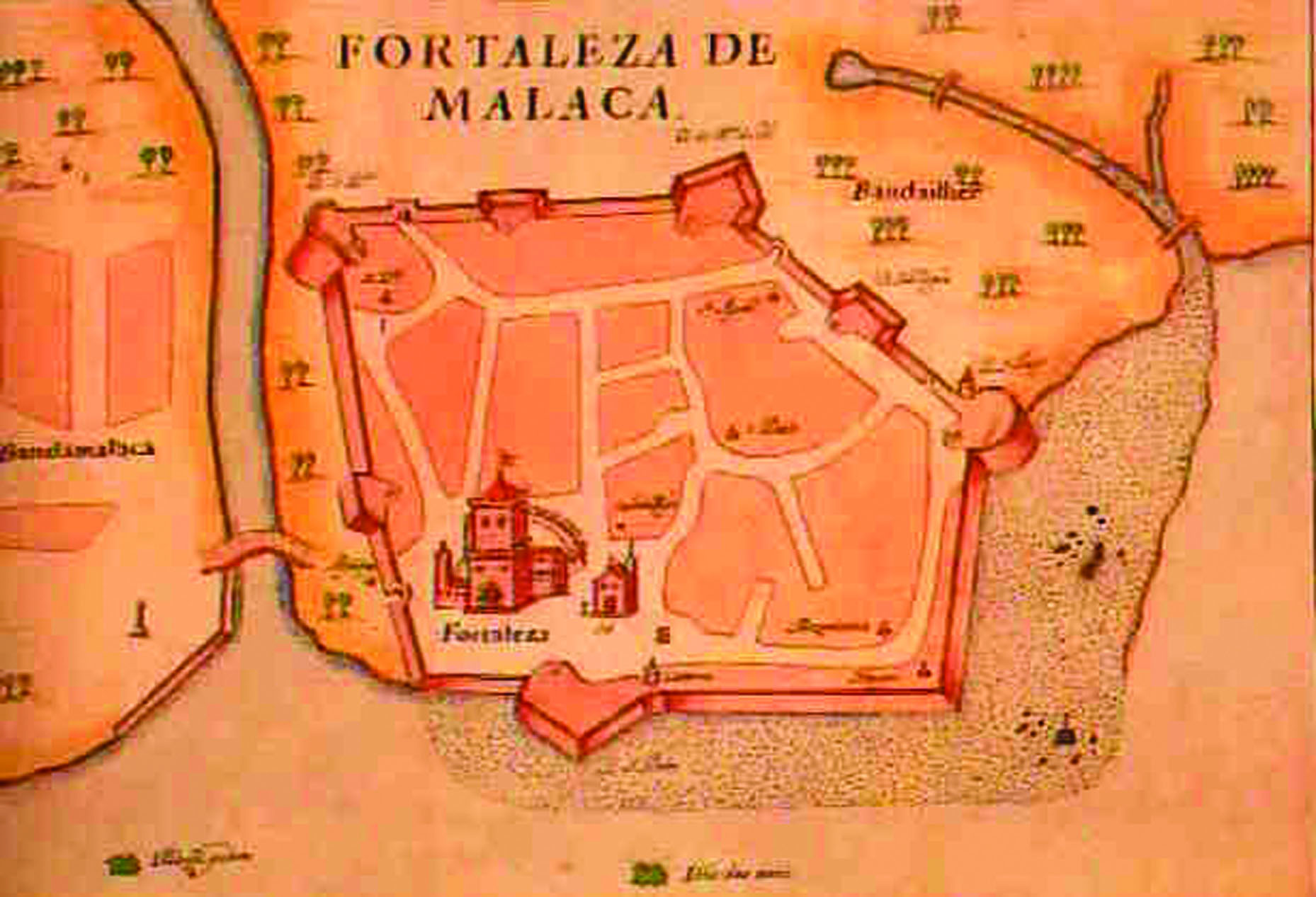

The built environment at Malacca was shaped by the Portuguese, most famously in their construction of the fort.

The fort was constructed with a thick heavy wall and was obviously designed to protect the city from attack. However, this creates a very strong separation of the city from the hinterland of the surrounding regions. And it was significant particularly when the city was ruled by foreigners. It had no strong relationship with the regions outside the city and this accelerated the development within Malacca of a distinct Malaccan city urban identity quite detached from the region around. The strength of the fort also suggests permanence to the Portuguese settlement.

The fort did not really replicate something that was in Portugal although it followed the building styles there. It has a fairly organic shape, responsive to the natural geography of the hill. The lack of a grand design for the city is an indication of several things about the Portuguese, one being that they did not know how long they would stay. And it is evident from Portuguese documents of the time that their goals towards the city were somewhat conflicted. Building forts was something that the Portuguese tended to focus on in their colonial efforts in other parts of the world, and a clear resemblance can be seen between the Malacca fort and those at Mombasa, Goa and elsewhere.

It is problematic to apply the notion of colony and the attendant philosophies to refer to the time when the Portuguese captured Malacca. The Portuguese did not establish a large settlement of civilians and they did not hold much territory beyond the borders of the city itself. However. their fortifications at least hinted at plans for permanence extending further than simply a factory. Nonetheless, their attitude towards the Malay Peninsula seemed ambivalent.

The idea of conversion to Catholicism was clearly part of the rhetoric of the Portuguese expansion. Nonetheless, the missions set up by the Jesuits, while endorsed by the Portuguese, were not really part of the official expansion nor were they something that the Portuguese crown invested in. It was very convenient to promote the idea of converting the Malay world from Islam to Christianity for audiences in Europe, particularly the Vatican, but in practice the Portuguese showed little interest in actually pursuing this.

The pre-existing town was sizeable, described thus in 1510: “In Malacca, there are approximately ten thousand homes, which are located along the sea and river. Those who live further away from the sea are at a distance of a little more than a cross-bow’s shot.”4 This assumes a population of at least 40,000, in housing clustered close to the sea.

Economically, the city was not a great success for the Portuguese. They were unable to regain the city’s prosperity when it was under the sultan. The Portuguese did act in accordance with their Christian expansionist plans to the extent that they limited Muslim trade in the town,5 which reduced profitability.

Macau’s duties paid to Malacca and Goa sustained Malacca.6 The true scale of the economy cannot be established, as much of it was unofficial, either held by private individuals or on the side (illegally) by agents of the state; aided by the loss of documents, and the fact that much of the empire “was created and functioned in the prestatistical age”.7

According to Victor Savage, Malacca was in the 16th century, as Ayuthia was in the 17th, a “comfortable and beautiful city for Western residents”.8 While Malacca might have been beautiful, it was not precisely a city on European lines. The largest reminders of the Portuguese were the fort and the church, which were reused by the Dutch. Savage’s description also hints at the evolving European taste for the exotic, in listing the destinations of luxury for European residents and the temporal/geographic shift around Asia.

Under the Dutch

When the Dutch took possession of Malacca, they did not attempt to do what they had initially done in Batavia (Jakarta today) – replicating a Dutch city. Likewise, they were not taking large numbers of civilian settlers to Malacca either. So it developed as an Asian city under European jurisdiction rather than a European city in the tropics. Direct European influence on architecture during the colonial period did not extend past official buildings.

Again, Malacca was not an economic success, as described in this account:

The Dutch built the State House and other administrative buildings, as well as private housing. But their arrival did not signal a rapid overhaul of the city, rather a slower evolution. The Dutch reuse of the fort demonstrated this continuity.9

Malacca was unique in the region for not relying on an agrarian hinterland, due to its “unusually favourable position”.10 This position depended on supplies from outside, and a level of trade to maintain them, which did not always hold under the Dutch.

Under the Dutch, there was a small European population. There was not much work for artisans and tradesmen,11 which meant that the European influence on material culture was less than in other colonies. Chinese and Indian artisans were often involved in construction and design. This led to the development of a unique visual idiom and these elements also helped to give the city (and its citizens) a particular identity.

The Dutch construction included St John’s Fort, which was sited for inland defence rather than defence against attack from the sea. As well as a demonstration of the politics involved, such an element of the built environment serves to imply a level of visual hostility to the surrounding area, and to reinforce insularity to the city.

MALACA,

Which is a Town belonging to the Company,

and was taken from the Portugueze.

This Place is very considerable, and much frequented

for Traffick, and is the Magazine

of the Eastern Trade, where all Nations, who

have frequented the Seas, met heretofore. At

present, its Trade is not near so considerable,

not sufficient to answer the Charge;

which Inconveniency might be remedied, by

sending thither a good Director; for it is certain,

that there is a good Vent in that Town

for great Quantities of Linnen Cloth, of all

sorts, as well as in many other Towns, its

Dependencies, or which lye round about it;

as Andragieri, and other Towns, and such

Places as lye along the Rivers of Sierra,

Perra, &c. where for the moft Part the Payments

are made in Gold and Tin, which is a Return

very rich, necessary, and profitable for the

Good and Support of the Trade of the Company.

Malacca is the Rendezvous of all the Vessels that return from

Japan every Year with their Cargoes, and which they there sort

and distribute, in order to their being sent to the [end p. 212] other

Store-houses on the Coast of India, Coromandel, Bengal, & c.12

Once again, we see a return to the standard descriptions of Malacca, that even in an account of its economic failure, it is referred to as the “magazine of the east” and in positive terms. Malacca’s ability to retain a positive image in European minds even as it was a poor investment merits further investigation, which I hope to pursue later.

The author wishes to acknowledge the contributions of Dr Merennage Radin Fernando, Senior Fellow, Humanities & Social Studies Education, National Institute of Education, Nanyang Technological University, in reviewing the paper.

Lee Kong Chian Research Fellow

National Library

REFERENCES

Barbara Watson Andaya, “Malacca Under the Dutch 1641–1795,” in Melaka: The Transformation of a Malay Capital, ed. Kernial Singh Sandhu and Paul Wheatley (Kuala Lumpur: Oxford University Press, 1983). (Call no. RSEA 959.5141 MEL)

David Dickson, Truth’s Victory Over Error (Edinburgh: [sn], 1684).

Gaspora Balbi, Viaggio Dell’indie Orientali (Venetia: Appresso Camillo Borgominieri, 1590).

George Bryan Souza, The Survival of Empire: Portuguese Trade and Society in China and the South China Sea, 1630–1754 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1986). (Call no. RCLOS 382.09469051 SOU)

Josede Acosta, The Naturall and Morall Historie of the East and West Indies (London: Edward Blount and William Aspley, 1604). (From BookSG; call no. RRARE 973.16 ACO; microfilm NL25702)

M.A.P. Meilink-Roelofsz, Asian Trade and European Influence in the Indonesian Archipelago Between 1500 and About 1600 (The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff, 1962). (Call no. RSEA 382.095 MEI)

Paul Wheatley, The Golden Khersonese (Kuala Lumpur: University of Malaya Press, 1961). (Call no. RSING 959.5 WHE)

Peter Heylyn, Cosmographie in Four Books: Containing the Chorographie and Historie of the Whole World, and All the Principal Kingdoms, Provinces, Seas, and Isles Thereof (London: Harry Seile, 1652).

Pierre D’ Avity, The Estates, Empires, & Principallities of the World, trans. E. Grimston (London: Mathewe Lownes and John Bill, 1615)

Pierre-Daniel Huet, Memoirs of the Dutch Trade in All the States, Empires, and Kingdoms in the World, trans. Samber (London: C. Rivington, 1719).

R. Araujo, “Letter to D. Afonso De Albuquerque, Malacca, 6 February,” in trans. M.J. Pintado, Portuguese Documents on Malacca, vol. 1 (Kuala Lumpur: National Archives of Malaysia, 1993). (Call no. RSEA 959.5102 PIN)

Radin Fernando, “Metamorphosis of the Luso-Asian Diaspora in the Malay Archipelago,” in Iberians in the Singapore-Melaka Area and Adjacent Regions (16th to 18th Century), ed. Peter Borschberg (Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz, 2004), 161–84. (Call no. RSING 959.50046 IBE)

Stuart B. Schwartz, “The Economy of the Portuguese Empire,” in Portuguese Oceanic Expansion, 1400–1800, ed. Francisco Bethencourt and Diogo Ramada Curto (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007), 19–48. (Call no. RSEA 325.34690903 POR)

Victor R. Savage, Western Impressions of Nature and Landscape in Southeast Asia (Singapore: Singapore University Press, 1984). (Call no. RSING 959 SAV)

NOTES

-

Paul Wheatley, The Golden Khersonese (Kuala Lumpur: University of Malaya Press, 1961), 138. (Call no. RSING 959.5 WHE) ↩

-

Gaspora Balbi, Viaggio Dell’indie Orientali (Venetia: Appresso Camillo Borgominieri, 1590). ↩

-

David Dickson, Truth’s Victory Over Error (Edinburgh: [sn], 1684). ↩

-

R. Araujo, “Letter to D. Afonso De Albuquerque, Malacca, 6 February,” in trans. M.J. Pintado, Portuguese Documents on Malacca, vol. 1 (Kuala Lumpur: National Archives of Malaysia, 1993). (Call no. RSEA 959.5102 PIN) ↩

-

Radin Fernando, “Metamorphosis of the Luso-Asian Diaspora in the Malay Archipelago,” in Iberians in the Singapore-Melaka Area and Adjacent Regions (16th to 18th Century), ed. Peter Borschberg (Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz, 2004), 162. (Call no. RSING 959.50046 IBE) ↩

-

George Bryan Souza, The Survival of Empire: Portuguese Trade and Society in China and the South China Sea, 1630–1754 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1986). (Call no. RCLOS 382.09469051 SOU) ↩

-

Stuart B. Schwartz, “The Economy of the Portuguese Empire,” in Portuguese Oceanic Expansion, 1400–1800, ed. Francisco Bethencourt and Diogo Ramada Curto (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007), 20. (Call no. RSEA 325.34690903 POR) ↩

-

Victor R. Savage, Western Impressions of Nature and Landscape in Southeast Asia (Singapore: Singapore University Press, 1984), 282. (Call no. RSING 959 SAV) ↩

-

Barbara Watson Andaya, “Malacca Under the Dutch 1641–1795,” in Melaka: The Transformation of a Malay Capital, ed. Kernial Singh Sandhu and Paul Wheatley (Kuala Lumpur: Oxford University Press, 1983), 200. (Call no. RSEA 959.5141 MEL) ↩

-

M.A.P. Meilink-Roelofsz, Asian Trade and European Influence in the Indonesian Archipelago Between 1500 and About 1600 (The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff, 1962), 7. (Call no. RSEA 382.095 MEI) ↩

-

Andaya, Malacca Under the Dutch, 206. ↩

-

Pierre-Daniel Huet, Memoirs of the Dutch Trade in All the States, Empires, and Kingdoms in the World, trans. Samber (London: C. Rivington, 1719), 212. ↩