The Myth of the “Squatter” and the Emergency Housing Discourse in Southeast Asia and Hong Kong

Lee Kong Chian Research Fellow Loh Kah Seng unpacks the myths and metaphors of informal housing in Southeast Asia and its associated postwar representations.

Before anger was expressed over “slum” in Danny Boyle’s popular, multi-Oscar winning movie Slumdog Millionaire (New York Times, 21 February 2009), representations of informal housing (otherwise known as “squatter” housing) played a much more prominent role in Southeast Asia and Hong Kong after World War II. Boyle’s film depicted the dwellers of an Indian slum to be both criminal and cosmopolitan, although critics focused on the former.

After the war, however, metaphors of contagion, crime and communism were commonly used to depict informal communities in Southeast Asia and Hong Kong. Framed by both the colonial and postcolonial states, these representations were much more discursive and invasive than their cinematic equivalents in Slumdog Millionaire. The postwar metaphors were a key part of an emergency housing discourse which conveyed no love for the slum, only a great anxiety to control them.

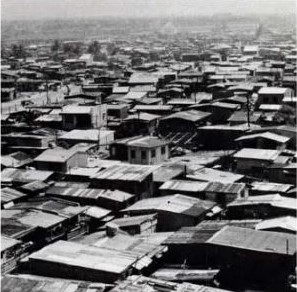

The very nature of informal housing was inimical to the states of Southeast Asia and beyond. James Scott has written about “high modernist” governments which embrace a robust “self-confidence about scientific and technical progress… and, above all, the rational design of social order commensurate with the scientific understanding of natural laws”. These states desired cities to be organised according to subscribed scientific-rational principles. In their view, the city, when seen from the air, should reveal itself as a “legible map”, whose “beauty” and “order”, it is argued, are expressed visually in the form of straight grid lines and clearly defined zones of planned building and infrastructure development (Scott, 1998, pp. 4–5).

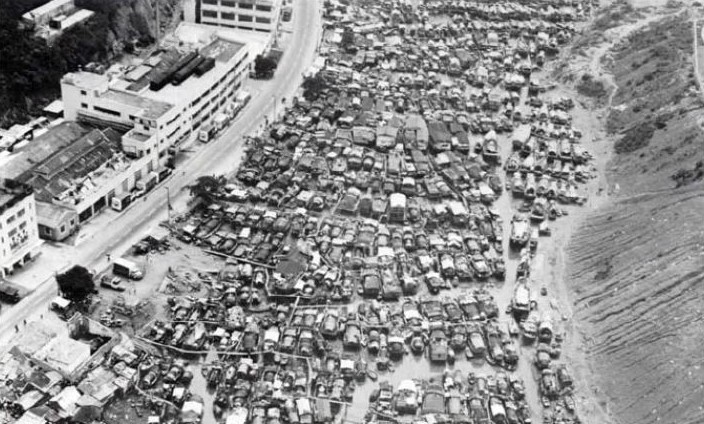

The classic informal settlement in postwar Southeast Asia and Hong Kong was anything but that. They were the unplanned products of a massive population boom and various forms of transnational, rural-urban and intra-urban migration of low-income families after the war (Yeung and Lo, 1976, p. xviii). By 1961, there were an estimated 750,000 informal dwellers in Jakarta (constituting 25% of the city’s population), 320,000 in Manila (23%), 250,000 in Singapore (26%), and 100,000 in Kuala Lumpur (25%) (McGee, 1970, p. 123).

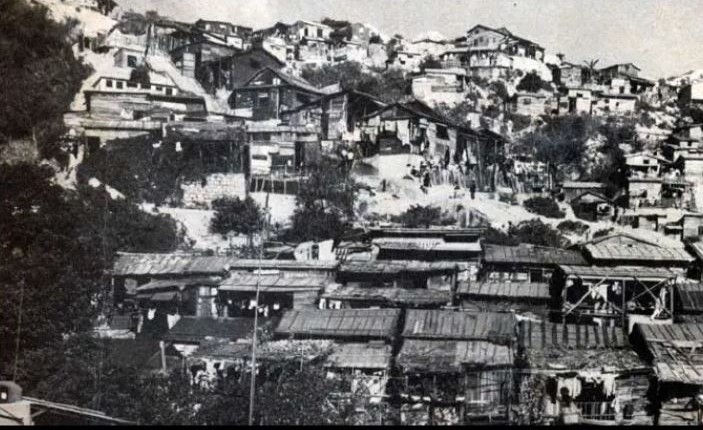

The informal house was typically built without planning approval and with light semipermanent materials such as wood, attap and zinc. The numbers of such housing grew rapidly after the war at the physical and administrative margins of the city: in war-damaged sectors; on steep hillsides, unused cemeteries and rooftops of existing shop houses; along railway tracks, dried up riverbanks and canals; in boats, foreshore areas and parks; and over swampy ground, disused mining land and rubbish dump sites (Sendut, 1976; Johnstone, 1981; McGee, 1967; Dwyer, 1976; Giles, 2003; Dick, 2003; Laquian, 1969; Stone, 1973). The peripheral locations of informal settlements caused the state much anxiety. They were spaces where official control was weakest and where, as the state feared, any social change could profoundly alter the character of society (Douglas, 2002, p. 150).

The official fear of informal housing did not arise merely over housing form or geography. It was deeply reinforced by how their residents, far from being disorganised and marginal, like the housing, formed dynamic social communities. On the one hand, as scholars in other contexts have observed, informal housing dwellers were well integrated into the politics and economy of the city and country (Perlman, 1976; Castells, 1983). On the other hand, the dwellers possessed their own networks of mutual self-help, much of which was frowned upon by the state.

There were numerous gangs based in the settlements, which recruited from among its youthful, under-employed residents. But in Manila, for instance, informal dwellers viewed their community as safe and harmonious, while also organising volunteer fire brigades and anti-crime patrols to safeguard their basic interests (Laquian, 1971, pp. 196–97). In short, the informal communities challenged the formal authority of the state. They constituted “the quiet encroachment of the ordinary” or the growing strength of “the weapons of the weak” (Bayat, 2004, p. 90; Scott, 1985, 1990).

It was in such a context, in which the balance of state-society relations was being redefined by the growth of the informal settlements, that the governments of Southeast Asia and Hong Kong created an emergency housing discourse. Governments in the region sought to bring informal housing under official regulation or even completely replace it with modern public housing. The basic aim was not just to change the form of shelter – it was, more ambitiously, to socialise semi-autonomous informal dwellers into becoming model colonial subjects and, subsequently, citizens of the high modernist state.

Discourse and Representation: Creating the “Squatter”

The first discursive act of the Southeast Asian state was to criminalise informal dwellers as “squatters”. The term conveys an instant impression of both illegality and social inertia and forges a powerful sense of social crisis. As Greg Clancey has argued, the colonial state in Singapore forged a controlling emergency discourse, which empowered it with the moral authority to intervene robustly in the everyday lives of ordinary people (Clancey, 2004, p. 53). In fact, most Chinese informal dwellers were not squatters but rent-paying tenants, having settled in autonomous housing as migrants from China and Malaya or from the overcrowded shop houses in the inner city after the war.

The Singapore Land Clearance and Resettlement Working Party of 1955, in fact, rejected the term “squatter”, as it had been “a long established custom in Singapore for owners of land not required for immediate development to rent out plots on a month-to-month basis and for the tenant to erect thereon a house” (Singapore, 1956, pp. 2–3). But its use persisted into the postcolonial period.

This criminalising discourse also appeared in postwar Thailand. Here, only a small minority of the informal dwellers were technically squatters. Like in Singapore, the majority were renters who had been granted permission on a temporary basis by landlords to build houses on their lands (Giles, 2003, p. 213). In Manila, too, many informal dwellers confidently viewed themselves not as squatters but as rent-paying tenants. In 1962, when the Philippine government sought to clear informal dwellers in Singalong and took them to court, the residents argued that they were not squatters but “lessees who had been paying rentals”. Such an assertive self-perception was rooted in the popular belief among Filipinos that public land in the country was not the possession of all but belonged to no one, and could be freely occupied (cited in Stone, 1973, pp. 40–43, 71–73, 80).

In Hong Kong, the illegality of “squatters” was based on a complicated official distinction between building land and agricultural land. This stipulated that residents could erect buildings only on the former. The distinction was made at the beginning of the 20th century and had been hotly contested. It could even lead to the criminalisation of residents who had built unauthorised houses on their own agricultural land. The legal distinction made it difficult for the private sector to satisfy the requirements of the complex building regulations to convert agricultural land into building land. The construction of informal wooden housing became illegal (Smart, 2003, pp. 212–213).

The use of a criminalising discourse of illegality and social inertia to provide the state with a powerful mandate to rehouse unauthorised housing dwellers in public housing in Southeast Asia and Hong Kong did not simply aim to represent. Rather, it sought to depict the “squatter” as the liminal Other who needed to be eliminated so that the city can be recreated in the political and public imagination (Mayne, 1990, pp. 8–9). Scholars in India have contended that the notion of illegality was, really, a fabrication since the laws of the state served chiefly the interests of the powerful. Cities, they argue, had always been built from the bottom up until recently; the poor had the right to build their own housing if the government was unable to provide for them (Desrochers, 2000, pp. 17–22, 27).

Transnational Roots and Western Advocates

The discursive vocabulary of “squatters” was common in official statements on housing in Southeast Asia and Hong Kong because it had strong transnational links and advocates. The 1951 United Nations Mission of Experts, which visited informal settlements in Thailand, India, Indonesia, Malaya, Pakistan, the Philippines and Singapore as part of its survey, reported that “squatting on somebody else’s land has become an art and a profession” in the Philippines (United Nations Mission of Experts, 1951, p. 157). Charles Abrams, an influential American urban planner in the post-war period, warned that informal housing dwellers formed a “formidable threat to the structure of private rights established through the centuries”, the rule of law and the basic sovereignty of the state (Abrams, 1970a, p. 11; 1970b, p. 143; 1966, p. 23).

Abrams and other Western urban planners such as Morris Juppenlatz frequently advised Southeast Asian governments on housing and urban planning after the war. Juppenlatz was a United Nations town planner who had worked in postwar Manila, Hong Kong and Rio de Janeiro. Drawing from the stark, powerful metaphors of disease and contagion, he represented informal housing as “a plague” and an “urban sickness”. Juppenlatz reveals his highly modernist mind in expressing his distaste for the physical appearance of informal settlements, where “[t]he outward appearance of the malady, the urban squatter colonies, when viewed from the air, from a helicopter, is that of a fungus attached to and growing out from the carapace of the city”.

He blamed many of the cholera outbreaks in Philippine cities on the physical environment of the informal settlements and the social habits of their residents. The basic solution, Juppenlatz urged, was to organise the residents’ integration into the state as tax-paying citizens. In this, the government’s role was pivotal and needed to be “based on the scientific method and planned urban development throughout the entire nation” (Juppenlatz, 1970, pp. 1–5, 41, 104, 212). Abrams had also warned that the “diseases of housing rival those in pathology” (Abrams, 1965, p. 40).

“Detrimental to Crime and Morals”: Contagion and the Gangs

British officials in the colonies fully endorsed these abject views of informal housing. In 1948, the British housing authorities in Malaya represented the “mushrooming” informal housing as being “temporary buildings of a very inferior type, erected without regard to the elementary requirements of sanitation, light and air” (cited in Johnstone, 1983, p. 298). In Hong Kong, similarly, the connection between the clearance of informal housing and state intervention into public health matters was similarly strong: informal housing became illegal when British colonial officials ruled it to be unhealthy for habitation (Smart, 2006, p. 32). In Singapore, the 1947 Housing Committee also reported that the unplanned urbanisation and development of slum and informal settlements in the city after the war were “detrimental to health and morals” (Singapore, 1947, p. 11), and in literally being “schools for training youth for crime” (Singapore Improvement Trust, 1947).

The likening of informal housing development to the spread of disease in official and even academic discourse underlines the social and moral danger the residents were alleged to pose. They were regarded not only as a threat to themselves but also to the fabric of society at large. Many official and academic commentators also did not fail to point to the alleged prevalence of crime and gangsterism in the informal settlements. Juppenlatz emphasised that the Oxo and Sigue Sigue – organised criminal gangs in Manila – were based in informal housing areas (Juppenlatz, 1970, p. 107). In Jakarta, groups of djembel-djembel (vagabonds), also based in slums and informal settlements, gained a reputation for being responsible for much of the crime in the city (cited in McGee, 1967, p. 159).

In Malaysia, increased overcrowding in the cities produced “a mood of urban anxiety”, with which not only the state but also the middle class viewed their values to be coming under severe threat (Harper, 1998, p. 218). The Ministry of Local Government and Housing depicted informal settlements in Kuala Lumpur in 1971 as “seedbeds of secret societies and racketeers” (Malaysia Ministry of Local Government and Housing, 1971, p. 42).

In Singapore, too, the government portrayed slum and informal housing as “breeding grounds of crime and disease”, noting that “[t]he incidence of tuberculosis is higher here than anywhere else on the island, as is the incidence of crime and gangsterism” (Choe, 1969, p. 163).

Masses and Mobs: Anglo-American Fears of Communism

Another international dimension of the emergency housing discourse was related to the Cold War and the attempt of Western planners to determine the character of postcolonial societies in Southeast Asia. Informal residents, understood to be resistant to resettlement, were seen to constitute “a potentially dangerous mass of political dynamite”, wherein lay the deadly possibility for antiestablishment and revolutionary politics (McGee, 1967, p. 170). Abrams acutely feared that the rural-urban migration was leading many Asian cities to relive the unfortunate history of Western cities:

“[Asian cities] have become the haven of the refugee, the hungry, the politically oppressed. The Filipino hinterlanders fleeing the Huks pour into Manila, the Hindus escaping the Moslems head into New Delhi, and the victims of Chinese communism head into Hong Kong” (Abrams, 1966, p. 10).

In Malaya, the British perceived locally born Chinese of the first generation, who did not speak English and whose fathers were immigrants, as a great menace to peace; their numbers were “expanding in labour forces and squatter settlements … [and] nothing can be done to convert them into Malayan citizens” (Britain, Colonial Office, 1948). The postcolonial Malaysia state, which won with British support the counter-insurgency struggle against the communists, also maintained that the clearance of informal housing was “not only in the best interests of Kuala Lumpur as a capital city but also to foster economic growth, improve social standards and improve security, thereby making for greater political stability” (Malaysia Ministry of Local Government and Housing, 1971, p. 29).

In 1968, political scientist Samuel Huntington wrote of how an enforced programme of urbanisation in South Vietnam offered an important way for the anticommunist regime to defeat the Vietcong insurgents based in the countryside (Huntington, 1964, pp. 648, 652).

The fear of communism was deeply embedded in the minds of Western, particularly American, urban planning experts. It forged a strong link between their ideas and practices and the rehousing programmes which emerged in postwar Southeast Asia. As Abrams warned, unlike the institutional and cultural buffers which existed against communism in Europe, Asian countries were openly vulnerable to the spread of communism. The “housing famine”, he cautioned, could easily encourage the ascendancy of Marxism, where “today’s masses” could turn into “tomorrow’s mobs”.

Such an ideological view of urban housing reflected Abrams’ belief that the city was the frontier in the postcolonial struggle to establish peaceful, democratic and stable societies in the less developed world. Asian cities were not only sites of great social and demographic growth; they were also politically explosive places, where the housing crisis represented a serious threat to both national development and global stability (Abrams, 1966, pp. 287–88, 296). The 1962 United Nations Ad Hoc Group, which Abrams chaired, likewise believed that housing and urban development were activities in which “social and economic progress meet” (United Nations, 1962, pp. 1, 9–19).

Conclusion

In postwar Southeast Asia and Hong Kong, powerful emergency housing discourses were forged by the colonial regimes and subsequently embraced by their successor states. But only the city-state of Singapore and Hong Kong successfully adopted policies of social governance which approached the “high modernist” model. The governments of Singapore and Hong Kong overrode organised opposition to replace superficially “messy” informal settlements with visually legible modern housing estates. Both governments possessed the will to transform their subjects into model citizens towards achieving broader developmentalist goals.

One was a non-representative colony which did not have to contend with democratic politics, while the other was an elected postcolonial government which tolerated little opposition and dominated domestic politics. Both also launched their public housing programmes in the context of major states of emergency occasioned by the outbreaks of great fires in settlements of informal housing (Castells et al, 1990; Smart, 2006; Loh, 2009).

Elsewhere in Southeast Asia, both the colonial and postcolonial governments were unable to integrate semi-autonomous informal communities into the formal structures of the state (Dwyer, 1975; Ooi, 2005). The postcolonial state was typically the patron of the citizenry, including the informal communities. They usually failed to obtain the requisite political hegemony to push through unpopular housing reforms.

In the Philippines, informal dwellers, local politicians and senior administrators held too much political influence for the state to carry out a sustained campaign of eviction and resettlement. By contrast, the Thai, Indonesian and Malaysian states were not genuinely democratic. But they were also too reliant on patronage politics for political legitimacy to ignore the importance of votes found in informal settlements at the margins of the city (Dick, 2003; Stone, 1973; Laquian, 1966).

In Manila, both national and local politicians were bound up in a mutually beneficial relationship: both needed each other to win elections. They also aligned themselves with informal dwellers to win votes, while the residents themselves made use of such patronage to resist eviction and win lawful tenure of their occupation from the state (Laquian, 1966, pp. 54, 118). The result of these complicated tangles of state-society relations was that most Southeast Asian states usually embarked on limited, short-term and visible “prestige projects”. T.G. McGee has observed that “national prestige, more than national concern for the social welfare of squatters, has been the most active force leading to their shift in these two cases”, but this, in the final analysis, merely maintained the status quo (McGee, 1967, pp. 169–70).

The region’s states floundered in tackling the informal housing issue in characteristic ways: forming numerous public agencies to disguise a lack of political authority and commitment, without being able to coordinate these agencies, and lacking comprehensive planning, sufficient resources and proper legislation and bylaws (United Nations Mission of Experts, 1951; Sicat, 1975).

Nonetheless, despite the failure of most Southeast Asian states to remove their informal settlements, it remains crucial to highlight the role played by the accompanying emergency housing discourse. Compared to the actual dis-housing efforts, the discourse was much more invasive. By representing informal dwellers as criminal, inert, unsanitary and, above all, dangerous populations, high modernist states were framing these part-autonomous, part-integrated communities of people as the Other. Such discursive views of “slum dwellers” and “squatters” have entered into popular consciousness and are uncritically accepted as “common sense” truisms, even before the making of Slumdog Millionaire. In the process, the states have been able to establish political hegemony over matters of what constituted modern, healthy housing and living and what the character of the model citizen was to be in postwar Southeast Asia and Hong Kong (Gramsci, 1992).

The author wishes to acknowledge the contributions of Professor Alan Smart, Department of Anthropology, University of Calgary, in reviewing the paper.

Lee Kong Chian Research Fellow

National Library

REFERENCES

Asef Bayat, “Globalisation and the Politics of the Informals in the Global South,” in Urban Informality: Transnational Perspectives from the Middle East, Latin America, and South Asia, ed. Ananya Roy and Nezar AlSayyad (Lanham: Lexington Books, 2004), 79–104.

Alan Choe, “Urban Renewal,” in Modern Singapore, ed. Ooi Jin-Bee and Chiang Hai Ding (Singapore: University of Singapore, 1969), 161–70. (Call no. RSING 959.57 OOI)

Alan James Christian Mayne, Representing the Slum: Popular Journalism in a Late Nineteenth Century City (Melbourne: University of Melbourne, 1991).

Alan Smart, “Impeded Self-Help: Toleration and the Proscription of Housing Consolidation in Hong Kong’s Squatter Areas,” Habitat International 27, no. 2 (June 2003): 205–25.

Alan Smart, The Shek Kip Mei Myth: Squatters, Fires and Colonial Rulers in Hong Kong (Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, 2006).

Antonio Gramsci, Prison Notebooks (New York: Columbia University Press, 1992). (Edited with an introduction by Joseph A. Buttigieg).

Aprodicio A. Laquian, The City in Nation-Building: Politics and Administration in Metropolitan Manila (Manila: School of Public Administration, 1966). (Call no. RCLOS 320.99141 LAQ)

Aprodicio A. Laquian, Slums Are for People: The Barrio Magsaysay Pilot Project in Urban Community Development (Manila: Local Government Center, 1969). (Call no. RUR SEA 301.3609599 LAQ)

Aprodicio A. Laquian, “Slums and Squatters in South and Southeast Asia,” in Urbanisation and National Development, ed. Leo Jakobson and Ved Prakas (Beverly Hills: Sage Publications, 1971), 183–204. (Call no. RCLOS 301.3630959 JAK)

Ceinwen Giles, “The Autonomy of Thai Housing Policy,” Habitat International 27, no. 2 (June 2003): 227–44.

Centre for Social Action (Bangalore, India), India’s Growing Slums (Bangalore: Centre for Social Action, 2000).

Charles Abraham, The City Is the Frontier (New York: Harper and Row, 1965).

Charles Abrams, Housing in the Modern World (London: Faber, 1966). (Call no. RUR 331.833 ABR STK)

Charles Abrams, “Slums,” in Slums and Urbanization, ed. A. R. Desai and S. Devadas Pillai (Bombay: Popular Prakashan, 1970), 9–14. (Call no. RUR SEA 711.59 DES)

Charles Abrams, “Squatting in the Philippines,” in Slums and Urbanization, ed. A. R. Desai and S. Devadas Pillai (Bombay: Popular Prakashan, 1970), 141–3. (Call no. RUR SEA 711.59 DES)

D.J. Dwyer, People and Housing in Third World Cities: Perspectives on the Problem of Spontaneous Settlements (London: Longman, 1975). (Call no. RUR 01.54091724 DWY)

D.J. Dwyer, “The Problem of in Migration and Squatter Settlement in Asian Cities: Two Case Studies, Manila and Victoria Kowloon,” in Changing South-East Asian Cities: Readings on Urbanisation, ed. Y.M. Yeung & C.P. Lo (Singapore: Oxford University Press, 1976), 131–41. (Call no. RSING 301.3630959 CHA)

Gregory Clancey, “Towards a Spatial History of Emergency: Notes From Singapore,” in Beyond Description: Singapore Space Historicity, ed. Ryan Bishop, John Phillips and Wei-Wei Yeo (London: Routledge, 2004), 30–60. (Call no. RSING 307.1216095957 BEY)

H. Gurney to Sir T. Lloyd, 8 October 1948, Enclosure “Groups in the Chinese community in Malaya”. (From Britain Colonial Office file no. CO 537/3758).

Hamzah Sendut, “Contemporary Urbanisation in Malaysia,” in Changing South-East Asian Cities: Readings on Urbanisation, ed. Y. M. Yeung & C. P. Lo (Singapore: Oxford University Press, 1976), 76–81. (Call no. RSING 301.3630959 CHA)

Housing Committee, Singapore, Report, 1947 (Singapore: Government Printing House, 1948). (Call no. RCLOS 711.4095951 SIN; microfilm NL10187)

Howard W. Dick, Surabaya, City of Work: A Socioeconomic History, 1900–2000 (Singapore: Singapore University Press, 2003). (Call no. RSING 330.95982 DIC)

Kementerian Penerangan, Malaysia Squatters in Kuala Lumpur (Kuala Lumpur: Jabatan Penerangan, 1971). (Call no. RUR SEA 711.5909595132.K8 MAL)

James C. Scott, Weapons of the Weak: Everyday Forms of Peasant Resistance (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1985). (Call no. RCLOS 301.444309595 SCO)

James C. Scott, Domination and the Arts of Resistance: Hidden Transcripts (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1990).

James C. Scott, Seeing Like a State: How Certain Schemes To Improve the Human Condition Have Failed (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1998). (Call no. RBUS 338.9 SCO)

Janice E. Perlman, The Myth of Marginality: Urban Poverty and Politics in Rio de Janeiro (Berkeley: University of California, 1976).

Land Clearance and Resettlement Working Party (Singapore), Report of the Land Clearance and Resettlement Working Party (Singapore: Government Printing Office, 1956). (Call no. RCLOS 711.4095951 SIN)

Loh Kah Seng, “The Politics of Fires in Post–1950s Singapore and the Making of a High Modernist Nation-State,” in Reframing Singapore: Memory, Identity and Trans-Regionalism, ed. Derek Heng and Syed Muhd Khairudin Aljunied (Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2009). (Call no. RSING 959.57 REF)

M. Castells, L. Goh, and R. Y.-W. Kwok, The Shek Kip Mei Syndrome: Economic Development and Public Housing in Hong Kong and Singapore (London: Pion, 1990). (Call no. RSING 363.556095125 CAS)

Manuel Castells, The City and the Grassroots: A Cross-Cultural Theory of Urban Social Movements (California: University of California Press, 1983).

Mary Douglas, Mary Douglas: Collected Works, 2 (London: Routledge Classics, 2003). (Call no. R 301 DOU)

Matias Echanove and Rahul Srivastava, “Taking the Slum Out of ‘Slumdog’,” New York Times, 21 February 2009, A21.

Michael Johnstone, “The Evolution of Squatter Settlements in Peninsular Malaysian Cities,” Journal of Southeast Asian Studies 12, no. 2 (September 1981): 364–80. (From JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website)

Michael Johnstone, “Urban Squatting and migration in Peninsula Malaysia,” International Migration Review 17, no, 2 (Summer 1983): 291–322. (From JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website)

Morris Juppenlatz, Cities in Transformation: The Urban Squatter Problem of the Developing World (St. Lucia: University of Queensland Press, 1970). (Call no. RUR SEA 301.363091724 JUP)

Richard L. Stone, Philippine Urbanization: The Politics of Public and Private Property in Greater Manila (DeKalb: Northern Illinois University, 1973) (Call no. RCLOS 346.59904 STO)

Samuel P. Huntington, “The Bases of Accommodation,” Foreign Affairs 46, no. 4 (July 1968): 642–56. (From JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website)

Sicat, G.M. (1979). “Housing Finance,” in Housing Asia’s Millions: Problems, Policies, and Prospects for Low-Cost Housing in Southeast Asia, ed. Stephen H. K. Yeh and A. A. Laquian (Ottawa: International Development Research Centre, 1979), 81–91. (Call no. RSING 363.5095 HOU)

Singapore Improvement Trust, “Notes for Discussion on Housing by Commissioner of Lands,” government records, 13 June 1947. (From National Archives of Singapore record no. SIT 475–47)

T.N. Harper, The End of Empire and the Making of Malaya (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1999). (Call no. RSING 959.5105 HAR)

T.G. McGee, The Southeast Asian City: A Social Geography of the Primate Cities of Southeast Asia (London: G. Bell and Sons, 1967). (Call no. RCLOS 301.3630959 MAC)

T.G. McGee, “Squatter Settlements in Southeast Asian Cities,” in Slums and Urbanization, ed. A.R. Desai and S. Devadas Pillai (Bombay: Popular Prakashan, 1970), 123–28. (Call no. RUR SEA 711.59 DES)

United Nations. Tropical Housing Mission, Low Cost Housing in South and South-East Asia Report of Mission of Experts, 22 November 1950–23 January 1951, no. ST/SOA/3/Add.1 (New York: United Nations, Dept. of Social Affairs, 1951).

United Nations. Ad Hoc Group of Experts on Housing and Urban Development, Report (New York: U. N. Ad Hoc Group of Experts on Housing and Urban Development, 1962).

Y.M. Yeung and C.P. Lo, eds. Changing South-East Asian Cities: Readings on Urbanisation (Singapore: Oxford University Press, 1976). (Call no. RSING 301.3630959 CHA)