Singapore and the Middle East: Forging a Dynamic Relationship

Researcher Bouchaib Silm considers the relationship between Singapore and the Middle East, how they can move towards a more vital and dynamic relationship, and how Singapore can play a pivotal role in reconnecting the Middle East with the rest of Asia.

While Singapore’s system of governance has proved its efficiency and sustainability, there are serious concerns about whether successful stories such as Singapore’s can serve to stimulate change in other countries, including those in the Arab world. Unfortunately, Arab societies tend to be conservative, and therefore lag behind in global integration.

History has shown that Arab culture is actually very dynamic and highly capable of learning and making progress. In the eighth century, the Abassid Khalif al Ma’mun, son of the famous Abassid Khalif Harun Al Rasheed, established the Bait al-Hikma (House of Wisdom) in Baghdad, Iraq. Al Ma’mun gave orders for important books in different fields of knowledge in the Greek, Persian and Indian languages to be translated into Arabic.1 Arab scholars accumulated a great collection of knowledge about the world, and built on it through their own discoveries.

Such achievements enabled the rise of the Arabic-speaking Islamic civilisation, which later became the blueprint for the European Renaissance. Meanwhile, the recent rise of an Arab business intelligentsia that is equipped with excellent educational qualifications and ready to face new challenges has demonstrated the ability of Arabs to learn from the experiences of others. For instance, the six countries of the Gulf Cooperate Council (or GCC), Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, Qatar, Bahrain, Kuwait and Oman, in general, and the United Arab Emirates in particular, offer clear examples of the readiness of the Gulf Arab societies to acquire new knowledge, and of how Arab societies can study and implement new knowledge that has been received from different societies.

A Region of Complex Images

Occupying a strategic location and possessing a wide array of natural resources, the Middle East is a region where the major powers have long competed to exercise their influence. Indeed, it has been an arena of conflict and cooperation that has helped shape the political, economic and security configurations of the world in which we live today.2

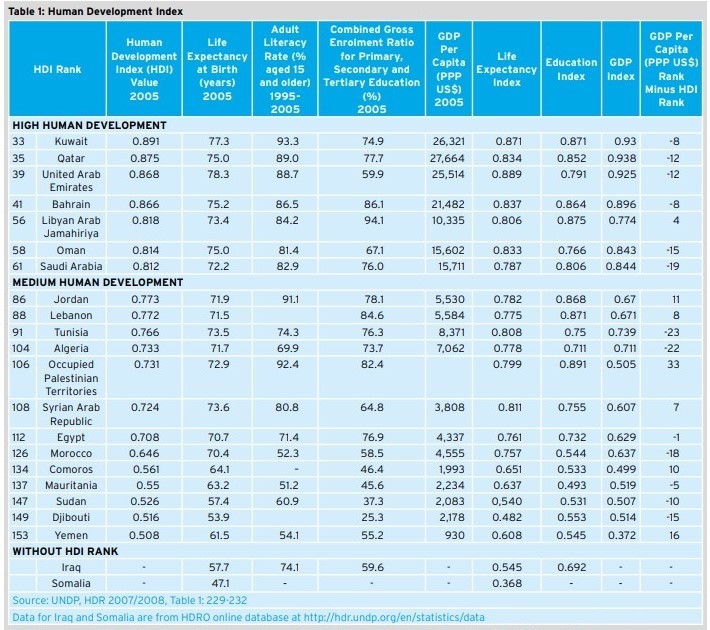

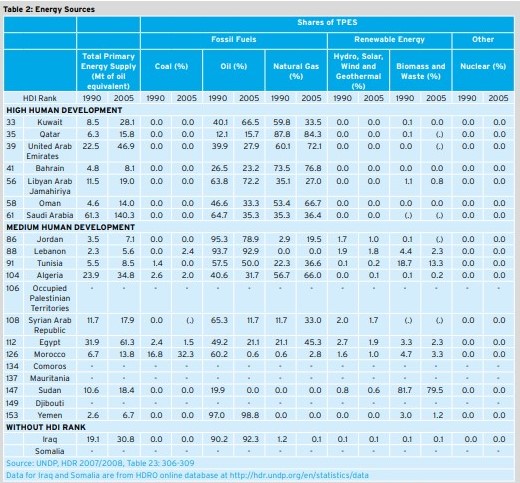

Meddling by foreign powers in the domestic politics of Middle Eastern countries has resulted in two distinct outcomes. First, Western intervention has led to the diversion of a large portion of oil revenues to military expenditure, rather than investing these funds towards economic progress.3 As is well known, the Middle East commands nearly three-fourths of the world’s oil reserves and has earned vast revenues from its oil resources.4

The second outcome is closely tied to the first. The involvement of the two Cold War superpowers – the United States of America and the Soviet Union – brought violence and uncertainty to the region, including the many wars and skirmishes that took place during the 20th century. Cases in point are the Arab-Israeli Wars of 1967 and 1973, the Iran–Iraq War from 1980 to 1988, Iraq’s invasion of Kuwait in 1990, America’s invasion of Iraq in 2003 and the persistent problem of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict and the Israeli-Hezbollah conflict in Lebanon.5

The recent escalation of tension between Iran and the United States over the Iranian nuclear programme has also led to speculation on the possibility of an imminent military confrontation between the two countries. If left unresolved, such a confrontation could lead to new military conflicts. On the other hand, we must not ignore the internal problems within the Middle Eastern countries: social and political problems, religious fanaticism, tribal conflicts, ideological extremism, dictatorships, and the denial of educational and professional opportunities to women in some Middle Eastern countries.

This list of problems could, perhaps, lead to a very negative impression of the region, a conclusion that would deny any hope for prosperity and peace there. But this is not the case. Despite political uncertainties and numerous other problems in the region, business opportunities are fast emerging in the GCC states. Some scholars and politicians have argued that the current changes in the Gulf states are a product of oil revenues, and that the oil and natural gas sectors are still predominant in their economies, rather than other sectors. However, this argument has no solid basis. The winds of change are blowing across the Middle East, and the clearest indication of this shift is the inflow of large amounts of foreign investment. State monopoly over economic resources has also given way to privatisation and, thus, to increased manoeuvering space for local companies.6

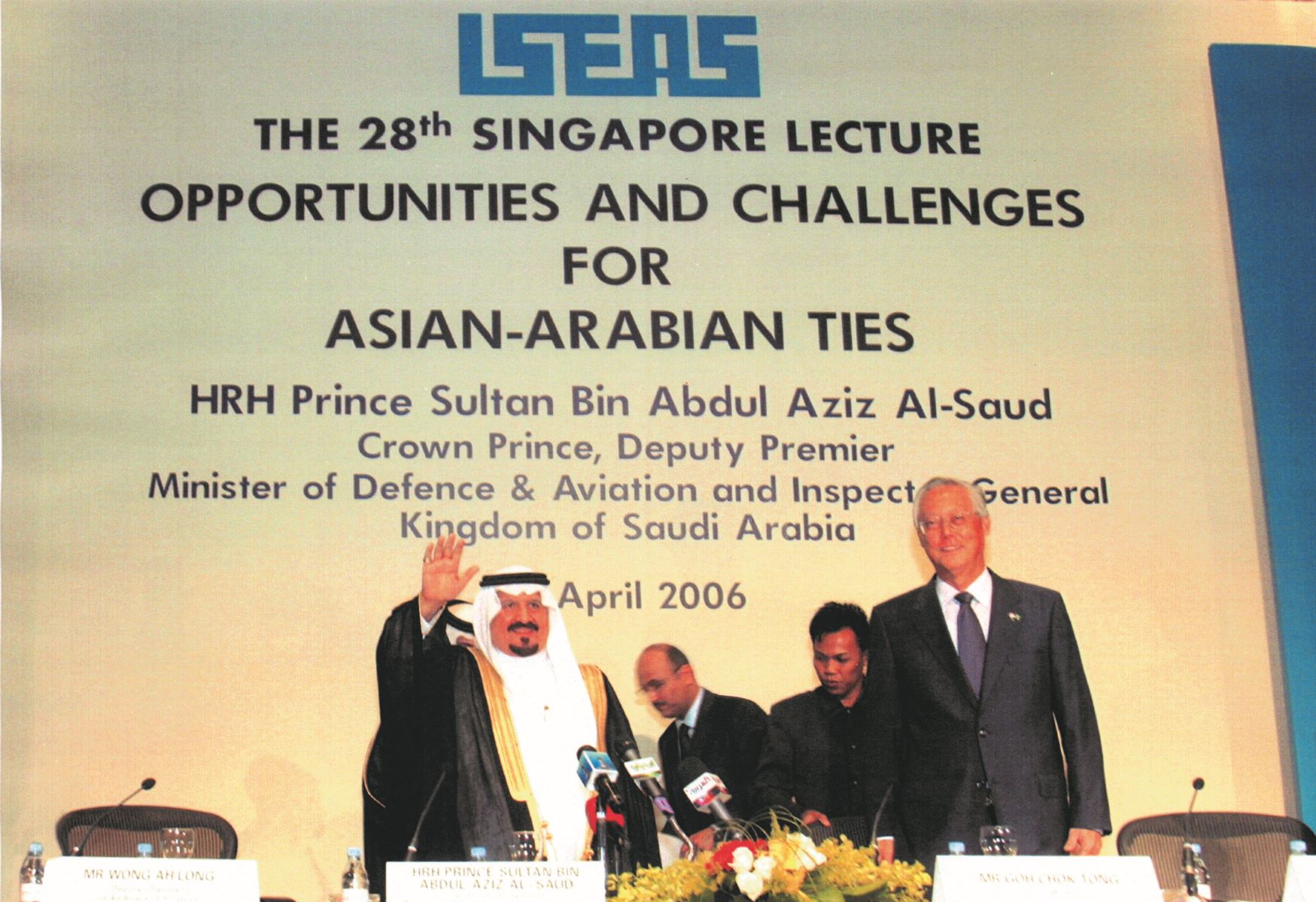

As Singapore’s Senior Minister Goh Chok Tong has rightly observed, the Middle East is “experiencing breathtaking development”.7 Like Singapore, the Gulf states are exploring the viability of creating, controlling and selling their technology. City-states such as Dubai in the United Arab Emirates have set an excellent example for other countries in the Middle East. In light of this, it is fair to assert that, while oil is certainly an enabling factor, it is not the determining factor for the region’s economic progress. The Middle East has slowly responded to the changes taking place in the world,8 but a great deal of work and determination are still needed. For instance, there is a strong need for economic integration in order to give the region a major role in the global economy.9

Singapore and the Middle East: Increasing Mutual Cooperation

Serious engagement between Singapore and the Middle East began in 2004, when Mr Goh made several official visits to the Middle East.10 These visits were soon followed by Singapore’s hosting of the inaugural Asia-Middle East Dialogue (AMED) in June 2005, which offered an opportunity for Middle Eastern representatives and their counterparts from other Asian countries to discuss issues of mutual concern.11 AMED enabled policymakers, intellectuals and businessmen to discover a wide range of opportunities for cooperation, and led to several bilateral agreements between their countries.

As a follow-up, the Singapore Business Federation (SBF) launched the Middle East Business Group in March 2007, which set out with two primary objectives: to foster strong ties between business chambers and companies from both sides, and to provide consultations for local companies with business interests in the Middle East.12 Even so, the options for economic cooperation between Singapore and the Middle East have been relatively few, regardless of the opportunities. One reason for this could be the Western-centric approach of Singapore’s foreign policy. Recent events, such as the 11 September 2001 attacks on the United States of America, have resulted in a shift towards the promotion of a more intensive Asia-Middle Eastern engagement.

Knowledge Is Power

Education is the conduit that connects the leadership of a modern nation-state to the population, since the national leadership disseminates its policies to the people through this channel. Education is responsible for establishing lines of communication between the leaders and the citizens. In the case of Singapore, education has produced a generation of Singaporeans trained in modern science, and able to change and adapt to new technologies. In fact, education has helped create a favourable framework for policymakers to disseminate their programmes. Indeed, no matter how brilliant the leaders are or how clear their strategies and planning, they cannot possibly share their ideas and views with an illiterate society. The success of the strategy depends on the general population; if the majority of the population is ignorant, any plan for progress will surely fail. Therefore, educating the people should be the foundation of any leader’s vision. Education can produce citizens with whom the leadership can communicate, and among whom can be found the future leaders of the country. This is as true for the Gulf states as it is for Singapore.

Dynamic Governance

This paper suggests that economic development is the yardstick by which the success of any state is determined. Economic development promotes social and political stability. Although there may be no worldwide unanimous agreement on the criteria for achieving good governance, it is clear that good governance has the ability to transform societies and promote development, as well as social stability and peace. In the case of Singapore, the good governance provided by its leadership has transformed this nation from a Third World country to a First World success story. The combination of courage, determination, commitment, character and ability on the part of its leaders have ensured their people’s willingness to follow their leadership.13

Such values are clearly demonstrated in the behaviour of the government during times of conflict, as well as in times of peace. A dynamic approach is a vital factor, as this determines the capability of a given leadership to maintain its legitimacy. In their book Dynamic Governance: Embedding Culture, Capabilities and Change in Singapore, Neo Boon Siong and Geraldine Chen listed three characteristics for a dynamic government:

First, the government has to think ahead, so as to identify areas for future development and set goals, as well as devise strategies to achieve those goals.14 In the absence of this factor, the government will be left to merely react to new developments in times of shock and fear.15 In Singapore’s case, the civil servants have succeeded in accomplishing almost all the plans that have been made by the leadership. Minister Mentor Lee Kuan Yew himself acknowledged the role of this group of people, and attributed Singapore’s success to them. He said: “The single decisive factor that made for Singapore’s development was the ability of its ministers and the high quality of the civil servants who supported them.”16 In the book The Modern Prince: What the Leaders Need to Know Now, Garnes Lord explained that Lee set down several criteria when selecting the civil service team. These criteria included the power of analysis and imagination, as well as a sense of reality.17

Second, since to err is human and it is only natural to make mistakes, a dynamic government must not be reluctant to review its performance objectively, and it must be ready to revise its policies whenever necessary. One may argue that when a government revises its original position, it implies that it is incompetent. However, this argument is deeply flawed and disregards the fact that no one is infallible, including government leaders. A leadership that refuses to accept that it has failed will produce a society that is unable to learn from its own mistakes. On the other hand, revising one’s previous position is a crucial factor that sets a successful government apart from a failed regime. It “requires leaders who are willing to confront the realities of current performances and feedback, and to challenge the status quo”.18

The third characteristic of a dynamic government is its ability to “think across” traditional orders and boundaries in order to learn from the experiences of others.19 What happens when the set agenda does not work, and when there is an urgent need for a change in strategy? How can a leadership think of new ways to achieve its agenda, and where can the new ideas be found? Barriers against sharing ideas for development are dissolved when leaders, as well as individual citizens, become eager to share their success with other nations through the media and cooperative exchange programmes. To learn from its own mistakes while following the examples of others does not undermine the legitimacy of a country’s leadership. Instead, these characteristics reflect the open-minded spirit of learning new ideas and strategies, while also accepting the inherent limitations of the human condition.

To succeed, a society must allow and encourage its people to innovate and think into the future, and it must also refrain from making harsh judgments against those who have failed. A society that opens its people’s minds to learn from the experiences of others is a dynamic society that is able to differentiate between pride and pragmatism. Refusal to do so will only result in isolation in an increasingly globalised world.

Singapore enjoys an outstanding reputation in the eyes of its neighbours and the international community as a whole. Its sophisticated infrastructure and strategic location, combined with the business-friendly environment of this island city-state, are just a few of the many factors that have made Singapore the ideal country to take the lead in reconnecting the Middle East with the rest of Asia. To highlight one example: Singapore enjoys excellent bilateral relations with China. The value of trade between the two countries reached US$20 billion in 2003. It further increased to more than US$30 billion in 2005 before hitting nearly US$40 billion for the first 10 months of 2006, and accounting for more than 10% of Singapore’s total foreign trade.20 Singapore was China’s seventh-largest international trade partner and China’s top trading partner among the ASEAN nations.21

Singapore is therefore highly qualified to take the lead in increasing economic ties between Asia and the Middle East. Indeed, its sophisticated infrastructure, strategic location and excellent relations with the Middle East are just a few of the driving factors that have put Singapore forward as an ideal trading partner for the Gulf states and the rest of the countries of the Middle East.

Although wars, conflicts and uncertainty are still shaping the Middle East, the region nevertheless preserves its uniqueness and appeal. However, if the political and security outlooks paint a pessimistic picture of the area, business opportunities and trade would appear to be far more promising. The winds of change are heading towards the region. Privatisation and foreign investments are just two of the signs of the changing trends that are permeating several aspects of life in the region.

According to the World Bank report Middle East and North Africa Region 2007: Economic Developments and Prospects, the region “has turned in strong economic performances, driven, to a large degree, by high oil prices and a favourable global environment, but also by reform policies that, though gradual, are generally on the right track. Growth in the region continues to be robust for the fourth year in a row”.22 Unfortunately, although there have been tremendous achievements recently in the GCC states, some other areas of the Arab world have not yet responded positively to international developments, especially those in the field of non-oil-related businesses. Hopefully, the GCC states can provide examples of success to be emulated by their neighbours.

Conclusion

Recent political, economic and social developments all forecast a revival of the Silk Road. History was always present in the establishment of connections between the different regions of Asia, as demonstrated by the trading links between the Middle East and Southeast Asia via Arab traders.23 These established networks wield the power to enable Singapore and the Middle East to enhance their patterns of cooperation and exchange, and to move towards a more vital and dynamic relationship. To be sure, Singapore can play a pivotal role in reconnecting the Middle East with the rest of Asia.

Singapore’s experience is also attracting the attention of other Asian states, including China and Taiwan, as well as many countries in Eastern Europe. It is unjust to narrow Singapore’s success to just a few factors. What has made Singapore what it is today is a system of policies, taking into consideration all aspects of life in this country, including the economy, education, research and development, and good governance. These policies have created an efficient government, effective leaders, successful citizens, an excellent educational system and a thriving economy.

Researcher

National Library

REFERENCES

Brian Whitaker, “Centuries in the House of Wisdom: Iraq’s Golden Age of Science Brought Us Algebra, Optics, Windmills and Much More,” accessed 13 July 2009, https://www.theguardian.com/education/2004/sep/23/research.highereducation1.

Cames Lord, The Modern Prince: What the Leaders Need to Know Now (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2003).

Goh Chok Tong, “The Opening Session of the Inaugural Asia-Middle East Dialogue (AMED),” Shangri La Hotel, Island Ballroom, Singapore, 21 June 2005, transcript, Ministry of Information, Communications and the Arts. (From National Archives of Singapore document no. 20050621989)

Hossein Askari, Middle East Oil Exporters: What Happened to Economic Development? (Cheltenham: Edward Elgar, 2006). (Call no. RBUS 338.956 ASK)

L.W.C. van den Berg, Le Hadhramout Et Les Colonies Arabes Dans l’Archipel Indien (Batavia, Impr. du gouvernement, 1886). (Call no. RRARE 325.25309598 BER; microfilm NL7400)

Lee Kuan Yew, From Third World to First: The Singapore Story, 1965–2000: Singapore and the Asian Economic Boom (Singapore: Times Editions, 2000). (Call no. RSING 959.57092 LEE)

Masoud Kavoossi, The Globalization of Business and the Middle East: Opportunities and Constraints (Westport, Conn.: Quorum Books, 2000). (Call no. RBUS 337.56 KAV)

Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Singapore, “Bilateral Relations: Middle East,” accessed 17 July 2009,

https://www.mfa.gov.sg/.

Neo Boon Siong and Geraldine Chen, Dynamic Governance: Embedding Culture, Capabilities and Change in Singapore (Singapore: World Scientific, 2007). (Call no. RSING 351.5957 NEO)

The Emirates Center for Strategic Studies and Research, Current Transformations and their Potential Role in Realizing Change in the Arab World (Abu Dhabi: Emirates Center For Strategic Studies And Research, 2007).

The Emirates Center for Strategic Studies and Research, International Interests in the Gulf Region (Abu Dhabi: Emirates Center for Strategic Studies, 2004).

The World Bank, Middle East and North Africa Region 2007: Economic Developments and Prospects (Washington: The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development, 2007).

NOTES

-

Brian Whitaker, “Centuries in the House of Wisdom: Iraq’s Golden Age of Science Brought Us Algebra, Optics, Windmills and Much More,” accessed 13 July 2009, https://www.theguardian.com/education/2004/sep/23/research.highereducation1. ↩

-

The Emirates Center for Strategic Studies and Research, International Interests in the Gulf Region (Abu Dhabi: Emirates Center for Strategic Studies, 2004), 1, 6. ↩

-

The Emirates Center for Strategic Studies and Research, International Interests in the Gulf Region, 83. ↩

-

Hossein Askari, Middle East Oil Exporters: What Happened to Economic Development? (Cheltenham: Edward Elgar, 2006), 83. (Call no. RBUS 338.956 ASK) ↩

-

Askari, Middle East Oil Exporters, 36. ↩

-

The Emirates Center for Strategic Studies and Research, Current Transformations and their Potential Role in Realizing Change in the Arab World (Abu Dhabi: Emirates Center For Strategic Studies And Research, 2007), 144. ↩

-

Goh Chok Tong, “The Opening Session of the Inaugural Asia-Middle East Dialogue (AMED),” Shangri La Hotel, Island Ballroom, Singapore, 21 June 2005, transcript, Ministry of Information, Communications and the Arts. (From National Archives of Singapore document no. 20050621989) ↩

-

The Emirates Center for Strategic Studies and Research, Current Transformations and their Potential Role, 148. ↩

-

Masoud Kavoossi, The Globalization of Business and the Middle East: Opportunities and Constraints (Westport, Conn.: Quorum Books, 2000), 146. (Call no. RBUS 337.56 KAV) ↩

-

“Bilateral Relations: Middle East,” Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Singapore, accessed 17 July 2009, https://www.mfa.gov.sg/. ↩

-

Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Singapore, “Bilateral Relations.” ↩

-

Singaporean companies have been very active in various business sectors in the Middle East, including petrochemical distribution, hotel development, water desalination, investment in petrochemical olefin projects, food manufacturing, e-government projects (for example, e-judiciary and e-trade projects), the sale of automotive parts, stationery and printing consumables, oil and gas parts and automotive parts, as well as oil and the petrochemical trade. “SBF Launches Middle East Business Group To Boost Business Ties Between Singapore and the Middle East.” ↩

-

Lee Kuan Yew, From Third World to First: The Singapore Story, 1965–2000: Singapore and the Asian Economic Boom (Singapore: Times Editions, 2000), 737. (Call no. RSING 959.57092 LEE) ↩

-

Neo Boon Siong and Geraldine Chen, Dynamic Governance: Embedding Culture, Capabilities and Change in Singapore (Singapore: World Scientific, 2007), 30. (Call no. RSING 351.5957 NEO) ↩

-

Neo and Chen, Dynamic Governance, 32. ↩

-

Lee, From Third World to First, 736. ↩

-

Cames Lord, The Modern Prince: What the Leaders Need To Know Now (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2003), 104. ↩

-

Neo and Chen, Dynamic Governance, 37–38. ↩

-

Neo and Chen, Dynamic Governance, 40. ↩

-

Neo and Chen, Dynamic Governance, 120. ↩

-

Neo and Chen, Dynamic Governance, 120. ↩

-

The World Bank, Middle East and North Africa Region 2007: Economic Developments and Prospects (Washington: The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development, 2007) ↩

-

L.W.C. van den Berg, Le Hadhramout Et Les Colonies Arabes Dans l’Archipel Indien (Batavia, Impr. du gouvernement, 1886), 104. (Call no. RRARE 325.25309598 BER; microfilm NL7400) ↩