A View from the Top: Williams Hunt Aerial Photograph Collection

Senior Librarian Makeswary Periasamy introduces aerial photographs gathered by P.D.R. Williams-Hunt, an aerial photograph interpreter for the Royal Air Force during and after World War II.

Introduction

The Williams-Hunt aerial photograph collection is a special historical collection of aerial photographs on Southeast Asia gathered by P.D.R. Williams-Hunt. Williams-Hunt worked as an aerial photograph interpreter for the Royal Air Force (RAF) during and after World War II. The photographs in the Collection were taken during the Royal Air Force’s reconnaissance missions, mostly in the 1940s.

There are about 5,800 photographs in the Collection, out of which 240 photographs are on Singapore. The National Library of Singapore acquired copies of 174 of the Singapore images.

This article is a brief introduction to the aerial photographs that Williams-Hunt gathered, as well as a look at Williams-Hunt himself.

Background

Many of the photographs in the Williams-Hunt collection were taken by the Allied Photographic Interpretation Service (APIS). (Lertlum & Moore, [198–?], p. 3) It was a unit within the RAF that specialised in gathering photographic intelligence. A few of the photographs were taken by Williams-Hunt himself, who also had an avid interest in archaeology and anthropology.

Before his untimely death in 1953, Williams-Hunt had passed his aerial photographs collection to his colleague and friend, John Bradford, in 1951. The collection was housed at the Pitt Rivers Museum. The museum subsequently passed the collection over to the University of London, where the photographs were scanned to create negatives. Currently, these photographs are held at the University’s School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS). (Lertlum & Moore, [198–?], pp. 1–2)

Dr Elizabeth Moore from SOAS found out about the collection when she was researching for her doctoral thesis on Northeast Thailand. Previously unorganised and without any explanatory data, Dr Moore helped organise the photographs by the various major locations in Southeast Asia and came up with a database to identify and inventorise the photographs (Lertlum & Moore, [198–?], p. 1).

The Center for Southeast Asia Studies (CSEAS) at the University of Kyoto has digitised the whole collection, making it accessible via a digital archive. (Lertlum & Moore, [198–?], p. 3). The digital archive, known as the “Geo-spatial Digital Archive for the Southeast Asia” is a collaborative effort between CSEAS, SOAS, the Chulachomklao Royal Military Academy (CRMA) and the Inter-University Network of Thailand (UniNet). Such efforts in inventorying and digitising have facilitated access to the rich trove of information available within these images.

Williams-Hunt, 1919–53

Williams-Hunt was born in Caversham, Berkshire on 2 July 1919 as Peter Darrell Williams-Hunt. He was interested in archaeology from a young age. While in his teens, he joined the Berkshire Archaeological Society and was actively involved in their fieldwork activities. By 1940, his name on the Society’s membership list was indicated as “P.D. Rider Williams-Hunt, Royal Fusiliers, Hounslow”. (Moore, 1984, p. 98–99). John Bradford notes that “Peter Williams-Hunt, F.S.A., F.R.A.I., A.M.A.” was “self-trained in observation and recording” and his early experience with field archaeology in Berkshire proved useful when he was in Southeast Asia after the Second World War. (Bradford, 1953, p. 175). For his obituary, F.M. Underhill wrote that Williams-Hunt was admired for his “acute powers of observation as an archaeologist” (Underhill, 1953, p. 8).

During World War II, Williams-Hunt joined the RAF as an Intelligence and Paratroop officer and assisted in aerial photographic interpretation. At the end of the war, he was based at the Army Photo Interpretation Unit located at North Africa and Italy. To his initial regret, Williams-Hunt was posted to the Far East in June 1945. He became more involved in aerial photographic interpretation while based in Singapore, Bangkok and Saigon for the next two years. With his experience, keen ability and the extensive resources available, Williams-Hunt made several significant archaeological discoveries from the air. He was also put in-charge of a huge library of aerial photographs on Southeast Asia, and henceforth devoted himself to aerial photo interpretation and the “assembling of his photographic library” (Bradford, 1953, p. 175; Moore, 1984, p. 99).

In Southeast Asia, Williams-Hunt became increasingly interested in anthropology and ethnology, studying tribal settlements and land use from the air and highlighting key techniques in his article “Anthropology from the Air”. (Bradford, 1953, p. 175) He also came into contact with the aborigines in Malaya. Upon demobilisation in 1946 and with the rank of Major, he stayed on in Malaya, devoting his time to researching the customs and beliefs of the aborigines. He took up residence with them, and in 1950, married Wa Draman, the daughter of a Semai tribal chieftain (Underhill, 1953, p. 8; Moore, 1984, p. 99).

The plight and suffering of the Malayan aborigines during the war went largely unnoticed. Their struggles were further aggravated by the Malayan Emergency. To help ameliorate their situation, Williams-Hunt recorded his observations of and interactions with the aborigines in his book Introduction to the Malayan Aborigines, published in Kuala Lumpur in 1952. It was an attempt to educate the Malayan government and the British security forces about the aborigines and their problems. Furthermore, he helped in the resettlement of the aborigines and “taught them improved farming methods and simple camp hygiene and showed the Army how to use them intelligently as guides and porters” (The Times, 15 June 1953, p. 5; Fagg, 1953, p. 8; Moore, 1984, pp. 98–99).

Williams-Hunt is often cited for his pioneering work in locating both archaeological and ethnological sites from the air in Malaysia, Thailand and Australia. Although he had written only nine articles from 1946 to 1952 and mostly brief ones, he was regarded as a pioneer of scientific air photography (Fagg, 1953, p. 8; Moore, 1984, p. 99).

Williams-Hunt was appointed as Adviser on Aborigines and later as Acting Director of Museums for the Federation of Malaya (Bradford, 1953, p. 175). Interestingly, he helped the British Museum collect aboriginal material culture, and sent rare orchids to the Singapore Botanical Gardens and zoological specimens to the Raffles Museum. He also assisted in the reconstruction of the Kuala Lumpur National Museum that had been demolished during the war (Fagg, 1953, p. 8; Moore, 1984, pp. 99–100; The Straits Times, 13 June 1953, p. 1).

On 3 June 1953, Williams-Hunt was in Tapah, Perak, to attend the wedding of his wife’s sister when he met with a fatal accident. He was crossing a wooden bridge when a rotten timber gave way and he fell. The bamboo pole supporting the bridge pierced him. Eight days after the accident, he passed away in Batu Gajah hospital, leaving behind a wife and three-week-old son named Anthony. (Moore, 1984, p. 100). The man who endeared himself to the aborigines and who was known affectionately among them as “Tuan Jangot” (Mr Beard) was buried in his wife’s jungle village near Tapah, according to Semai rites (The Straits Times, 13 June 1953, p. 1; The Straits Times, 15 June 1953, p. 1).

Details of Williams-Hunt Collection

The Williams-Hunt Collection at SOAS comprises the aerial photographs of the RAF gathered by P.D.R. Williams-Hunt, including some of his documents as well as maps and flight plans.

The main Southeast Asian countries represented by the photographs are Singapore, Myanmar, peninsular Malaysia, Thailand and Cambodia. Majority of the photographs in the Collection are vertical aerial images while “about 20 percent… [are]… lower-level oblique photographs (notably of Bangkok, Ayutthaya, Singapore and Saigon)” (McGregor, 1996, p. 208).

Table 1 highlights the geographical coverage and major timelines of the photographs in the Collection, based on the inventory and description done by Dr Elizabeth Moore.

The largest portion of the photographs is on Peninsular Malaysia, shot between 1947 and 1949. The earliest photographs will be those of Myanmar, shot between 1943 and 1944. Interestingly, almost “300 photographs exist of Japanese-occupied Rangoon”.

Most of the aerial photographs of Malaysia were taken by the British during the Malayan Emergency in order to discover “possible activity of Communist insurgents”. The aerial photographs are a “good record of land use, but are difficult to locate in the absence of flight plans and recognisable settlements or transport arteries” (McGregor, 1996, p. 208).

Details of Singapore Photographs

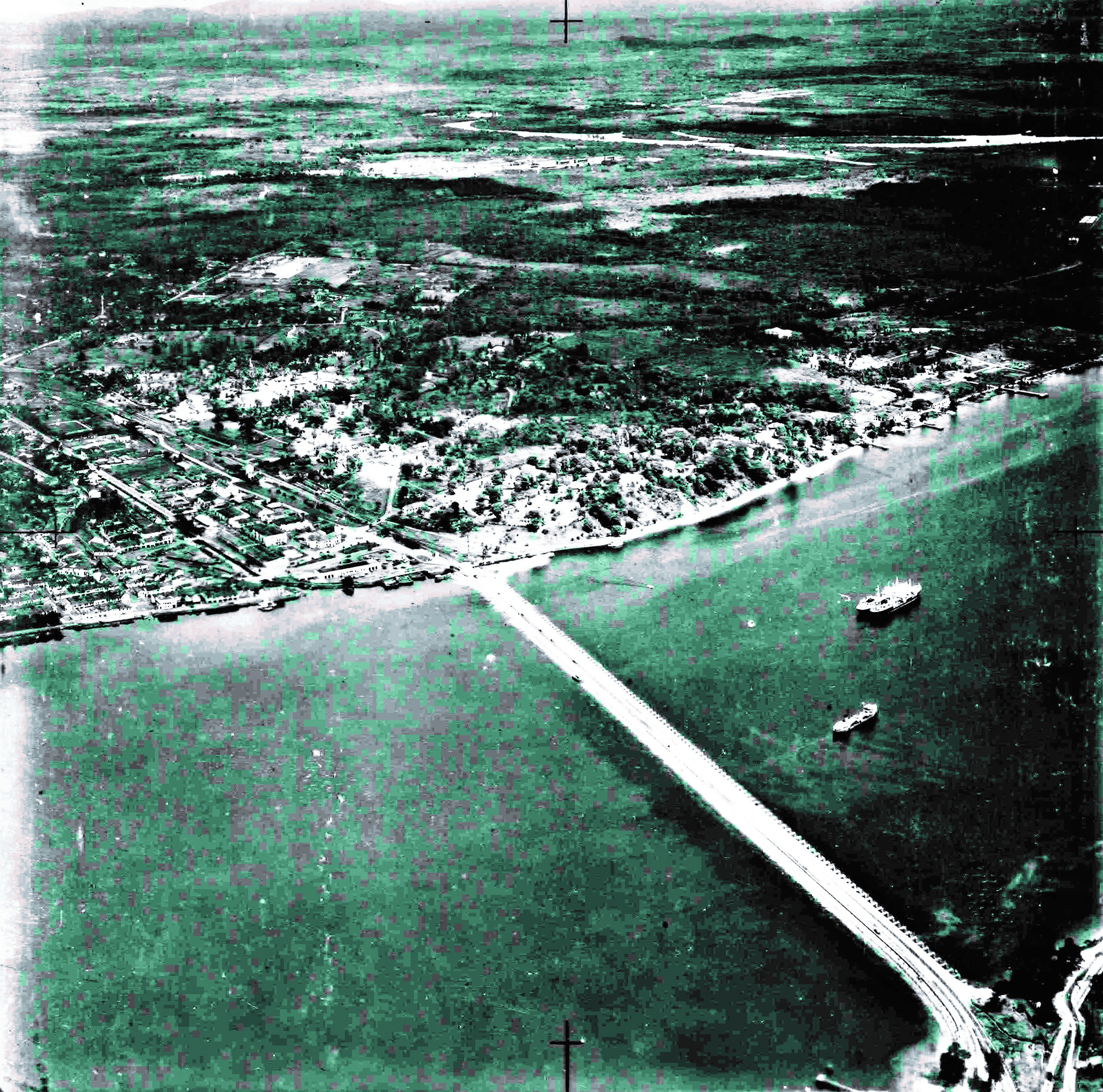

The aerial photographs on Singapore were mainly taken between 1947 and 1948 and are “all obliques” (McGregor, 1996, p. 208). The Singapore images depict aerial views of various parts of the island, including coastlines, waterfront areas, ports, warehouses, airfields, rural and suburban areas, and government, commercial and residential buildings.

The inventory listing that accompanied the Singapore photographs is based on the list Dr Moore created to sort the photographs in the Collection. A sample is provided below to show how the photographs were organised within the list.

The above list shows a broad organisation of the photographs by major locations in Singapore. Further investigation and research are required to identify the numerous details of Singapore landscapes evident in the images and to compare them with the current Singapore landscapes.

The National Archives of Singapore (NAS) holds a similar collection of Royal Air Force aerial photographs transferred to them by the Ministry of Defence, Singapore. These photographs span the period from 1946 to 1968. In their book, Over Singapore 50 Years Ago, Brenda Yeoh and Theresa Wong researched on the aerial photographs taken between 1957 and 1958. They meticulously identified the places and buildings portrayed within these images, as they existed then in the 50s. The authors have also added a current map of each of the areas studied to better understand the changes that have occurred (Yeoh & Wong, 2007, p. 7).

Conclusion

The aerial photographs of Singapore offer unique insights into how the island looked in the 1940s and 50s, and a view of the buildings that are long gone. They serve as a testimony to how Singapore’s landscape has changed over the years. Though originally taken for reconnaissance purposes, the aerial photographs provide an important visual study of the historical and socioeconomic development of Singapore.

On the whole, the Williams-Hunt Collection of Southeast Asian aerial photographs has been useful in researching into land utilisation in Southeast Asia, especially with the use of GIS technology. It has also proved useful for archaeological, anthropological and environmental studies. It is a unique and remarkable collection and “represents the oldest known freely available regional aerial photographic record of South-East Asia” (McGregor, 1996, p. 208).

The author would like to acknowledge the following people for their assistance with this article:

Azizah Sidek, Lee Kong Chian Reference Library, National Library Board; Associate Professor Robert J. Madden, Keene State College; Professor Brenda Yeoh, National University of Singapore; Yvonne Chan, National Archives of Singapore; Hayati bte Abdul, Central Library, National University of Singapore; Lim Ah Eng, Aodhfionn Quinn, Tony Lim Buck Chye, Malena Abdul Manaf & Rahmah Abdullah Bamadhaj, National Library Board for their assistance in interpreting the aerial photographs on Singapore; Dr Elizabeth Moore, School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London, for providing information and images readily.

Senior Librarian

Professional Services

National Library

REFERENCES

“Aborigine Burial of Mr Williams-Hunt: Jungle Rites,” The Times, 15 June 1953, 5.

Brenda Yeoh and Theresa Wong, Over Singapore 50 Years Ago: An Aerial View in the 1950s (Singapore: Editions Didier Millet in association with National Archives of Singapore, 2007). (Call no. RSING 779.995957 YEO)

Cultural Affairs Division, Ministry of Culture, Singapore 1870s–1940s in Pictures (Singapore: Ministry of Culture, Cultural Affairs Division, 1980). (Call no. RSING 779.995957 SIN)

D. McGregor et al., “Mapping the Environment in South-East Asia: The Use of Remote Sensing and Geographical Information Systems, in Environmental Change in SouthEast Asia: People, Politics and Sustainable Development, ed. Michael J.G. Parnwell and Raymond L. Bryant (London: Routledge, 1996). (Call no. RSEA 304.20959 ENV)

Elizabeth Moore, “Peter Williams-Hunt Remembered,” Purba (Journal of Persatuan Muzium Malaysia) 3 (1984), 98–103.

Elizabeth Moore, Inventory of Williams-Hunt Collection of Aerial Photographs of Mainland Southeast Asia (London: Institute of Archaeology of the University of London, 1986)

F. M. Underhill, “Obituary: Mr. P. D. R. Williams-Hunt: Devoted Worker Among Malayan Aborigines,” The Times, 16 June 1953, 8.

“Geo-Spatial Digital Archive for the Southeast Asia,” accessed 5 February 2009, https://intriguing-history.com/geo-spatial-digital-archive-se-asia/

Gretchen Liu, Singapore: A Pictorial History 1819–2000 (Singapore: Archipelago Press in association with the National Heritage Board, 1999). (Call no. RSING 959.57 LIU)

Ian Lloyd and Irene Hoe, Singapore From the Air (Singapore: Times Editions, 1985). (Call no. RSING 779.995957 LLO)

John Bradford, “Peter WilliamsHunt: 1918–1953,” Man 53 (November 1953), 175–76. From JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website)

“Mr P. D. R. Williams-Hunt,” The Times, 13 June 1953, 8.

“Mr Williams-Hunt Memorial,” The Times, 12 October 1953, 7.

Surat Lertlum and EliZabeth Moore, “WilliamsHunt Aerial Photograph Collection,” accessed 2 February 2009, http://www-archive.cseas.kyoto-u.ac.jp/www/2016/wp-content/uploads/2013/02/Williams-Hunt_collection.pdf.

“The “Tuan Jangot” Is Dead,” Straits Times, 13 June 1953, 1. (From NewspaperSG)

“The Sakais Weep,” Straits Times, 15 June 1953, 1. (From NewspaperSG)

William Fagg, “Obituary: Mr. P. D. R. Williams-Hunt: Devoted Worker Among Malayan Aborigines,” The Times, 16 June 1953, 8.