In Search of the Child: Children’s Books Depicting World War II in Singapore

Lee Kong Chian Research Fellow Khoo Sim Lyn sets out to discover children’s books written in English depicting World War II in Singapore.

Introduction

To people of my generation, World War II (WWII) in Singapore and Malaya was more than just a historical fact studied in history books because our parents had lived through the war. From their sporadic recollections, we created our images of what the war must have been like for them: for some, a time of terrible atrocities, and for most, a time of hardship and deprivation. However, as an avid child reader growing up in Malaysia and Singapore, and later as an adult reader of children’s books, it struck me that most of the books I had read depicting WWII were all set in Europe. Thus, the mental images created through my parents were not reinforced in the books I was able to lay my hands on. Imaginatively, at least, it seemed as if WWII in Europe, with images of children sent to the countryside to escape the bombing, of children coming upon an injured German pilot, of kind families sheltering Jewish refugees, was more real to me than WWII in my own region.

Thus, the focus of my research fellowship at the National Library of Singapore is on children’s books written in English which depict WWII in Singapore. As the focus is on imaginative literature, purely factual materials were excluded, but autobiographies were included as they resemble fiction in the way the narrative is used. The Asian Children’s Collection’s definition of children’s books to mean books “for children up to 14 years of age” (National Library Board, 2005a, p. 33) has also been adopted.

Two Main Categories

The books that portray WWII can be divided into two main categories:

• books that portray the war from the autobiographical or biographical point of view; and

• books written as fiction set during the war years.

Within these two categories, the books set in Europe cover an impressive range, from books suitable for older children to picture books for young children. Moving from older to younger children, autobiographical books include Anne Frank’s The Diary of a Young Girl (first published in 1947), The Upstairs Room by Johanna Reiss (1972) and When Hitler Stole Pink Rabbit by Judith Kerr (1971). Many good fiction books have been written, and continue to be written. These include Robert Westall’s The Machine-Gunners (1975), which won the Carnegie Medal, Michelle Magorian’s Goodnight Mister Tom (1981), which won the 1982 Guardian Fiction Award, and Number the Stars (1989), which won the 1990 Newbery Award. Other notable books include Friend or Foe (1977) and Waiting for Anya (1990) by Michael Morpugo, and James Riordan’s Escape from War (2005).

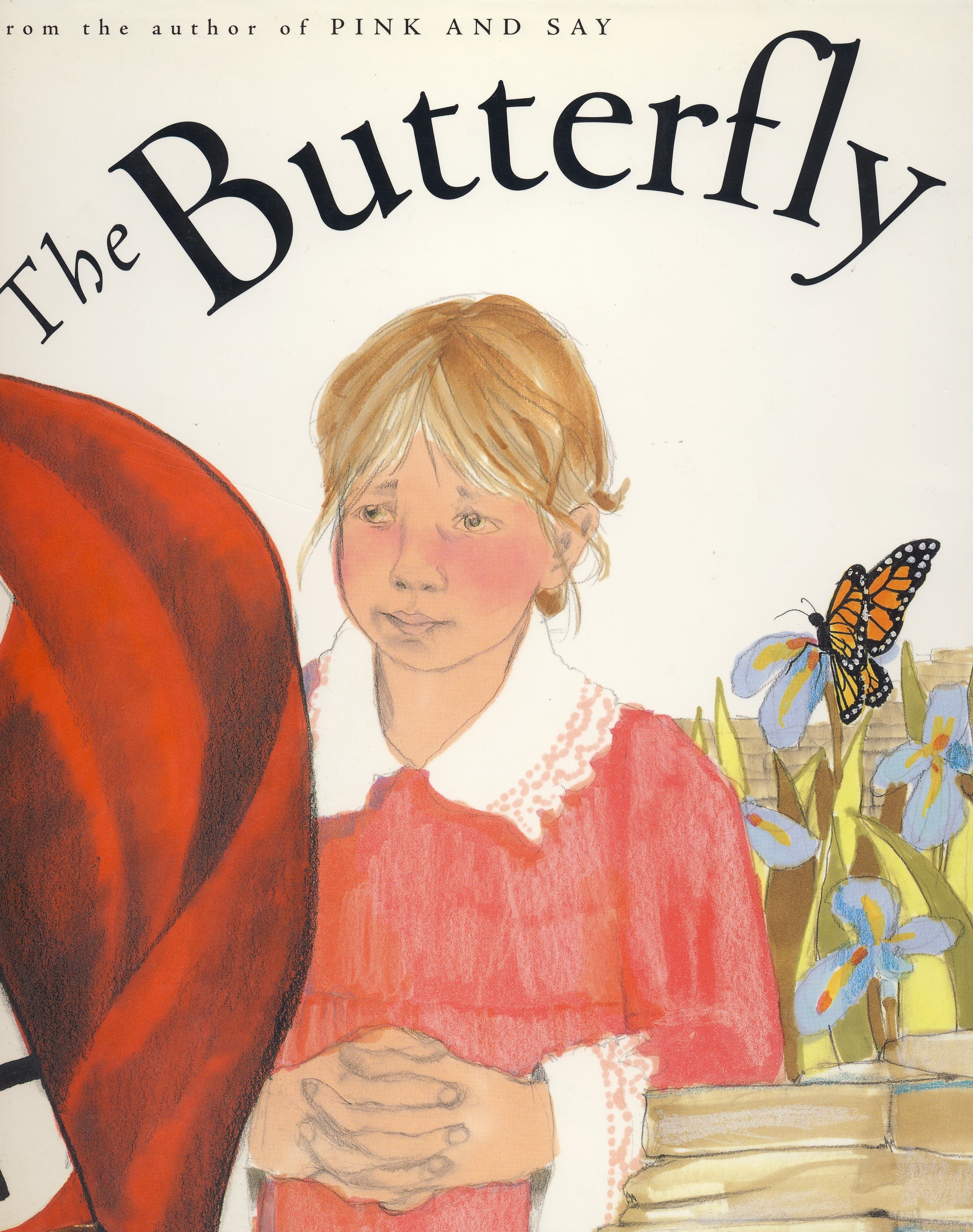

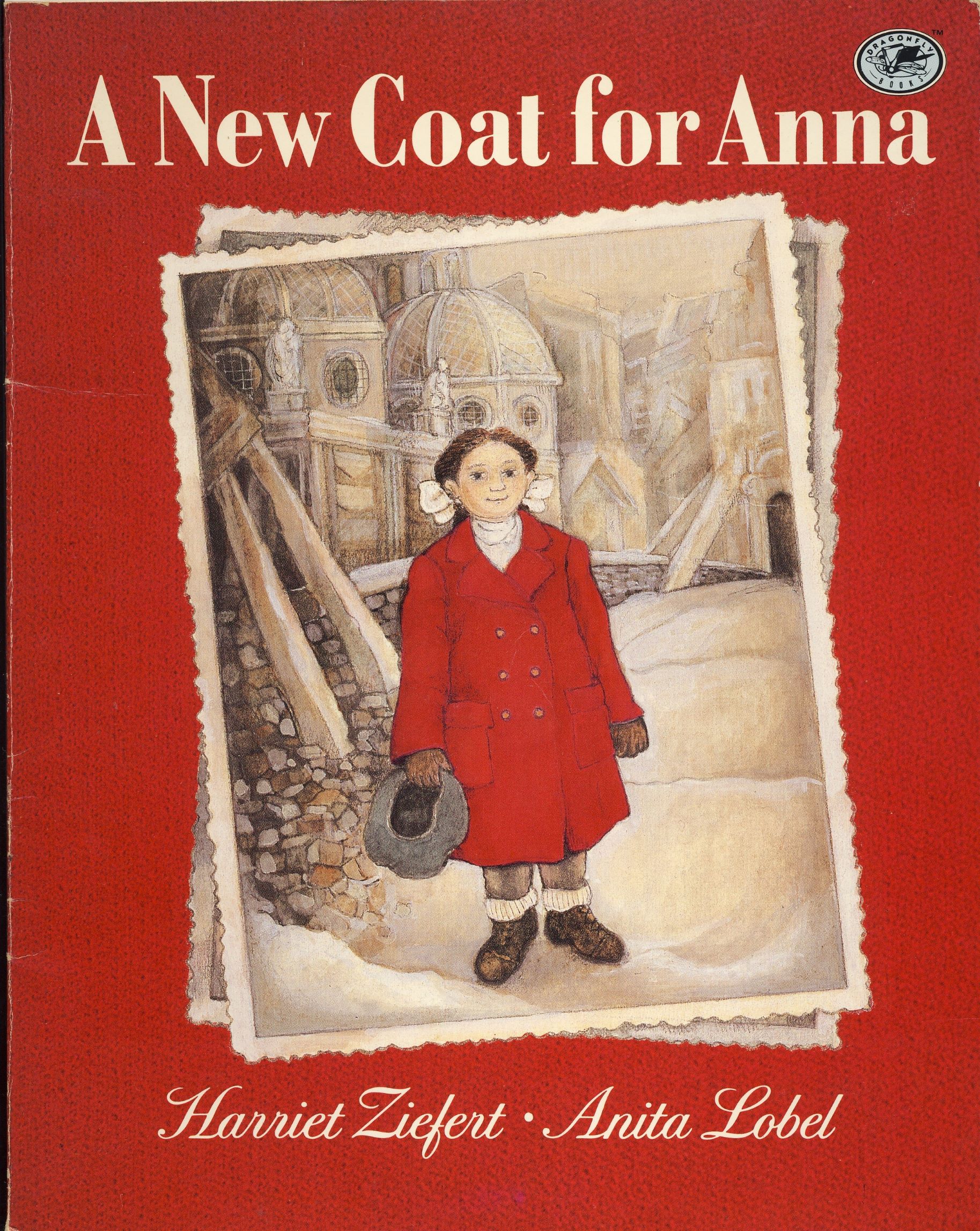

What is especially interesting is that there are also well-crafted picture books set during the war, which could be appreciated by younger children.

In The Butterfly by Patricia Polacco (2000), Monique, a young girl living in Nazi-occupied France, discovers that her mother has been sheltering a little Jewish girl in their house. The eventual discovery of the Jewish girl by the next-door neighbour leads to a dangerous journey at night to take her to another refuge. Polacco’s illustrations are hauntingly evocative, and capture the emotion of her young protagonists clearly. The book could easily be read to a child as young as six years old.

A New Coat for Anna (1986), written by Harriet Ziefert and illustrated by Anita Lobel, would appeal to an even younger child. The war has ended but people still have to cope with the shortage of food and goods of any kind. When Anna needs a coat for the winter, her mother uses her ingenuity to exchange various treasured items to obtain first the wool, and then the workmanship for the coat. It is a moving story of a mother’s love and perseverance during the difficult postwar period.

Apart from simply being stories poignantly told, such picture books help younger readers to gain an understanding of the impact the war had on the lives of children like themselves.

Sadly, the search for books set during the war in Singapore indicates that this broad range is missing. There are some books suitable for teenagers, a handful suitable for children, and hardly any for young children. Almost all the books are autobiographies or biographies. Therefore, there appears to be a dearth of children’s fiction depicting the war in this part of the world.

The Historian’s Viewpoint

The lack of interest in WWII is not new to historians, who have noted that when compared with Europe, there was “a relative absence of public commemoration of the war in this region” (Wong, 2000, p. 1). Not surprisingly, then, while WW II was well documented in Europe, the situation was quite different in Asia. Historian Wang Gungwu found that “some dramatic personal experiences did go on record, and some novels and short stories were set during periods of Japanese Occupation, but they were few” (2000, p. 11). P. Lim Pui Huen found that 50 years after the war, only about “50 odd volumes” (1995, p. 121) of autobiographies and memoirs of the war had been written by members of the local population of peninsular Malaysia and Singapore. While more autobiographies have surfaced from the intervening years, there has not been a significant increase.

Intended Audience

Among this relatively small number of autobiographies, few were written with the child reader in mind. Most were written for the general public. Many of the writers, who were children at the time of the war, wrote about their childhood memories of the war as adults looking back upon their childhood, so that the child protagonist is seen through the eyes of the adult narrator. Most writers who expressed the hope that their memoirs would enable young readers to better understand this period of Singapore’s history appear to have written for readers of approximately 14 and above. This is seen in Diary of a Girl in Changi (1941–1945) by Sheila Allan (1994, 2004), Rosie’s War: Escape from Singapore 1942 by Rosalind Sharbanee Meyer (2007), In the Grip of a Crisis by Rudy Mosbergen (2007), A Cloistered War: Behind the Convent Walls During the Japanese Occupation by Maisie Duncan (2004) and Escape from Battambang: A Personal World War II Experience by Geoffrey Tan (2001).

While these books are certainly valuable accounts of the war years, they may not be books that the child reader would choose to read simply because the intended audience is not the child reader. Who the author writes for will naturally affect the way the story is told. Hence, there is a clear difference between the intended audience of The Upstairs Room and Rosie’s War. Both books were based on the true experiences of their writers, Jewish girls who had to flee their homes during the war, and both are first-person narratives.

In Rosie’s War, the narrator is an adult recalling how she felt as a child, and her reminiscences are coloured by her adult reflections on her childhood feelings and experiences. Recalling the home she lived in before the war, she comments:

This is the adult Rosie trying to make sense of her childhood experiences. In contrast, there is no sense of the intrusion of the adult self upon the child protagonist in The Upstairs Room. The writer returns to the time when she was a child, and tells the story through the voice of Annie, the child narrator, who has just begun to realise what having to be confined to a tiny room for an indefinite period of time will entail:

The viewpoint is that of Annie the child, for whom the frustration of being cooped up overshadows the danger of discovery. It would appear that Johanna Reiss made a conscious decision to write her story for children, even as Rosalind Sharbanee Meyer chose to write hers for the general reader.

The Voice of the Child

To further illustrate this point, let’s briefly look at the books of Japanese-American writer, Yoshiko Uchida. During WWII, although she was an American citizen, Yoshiko Uchida was interned together with other Japanese-Americans because of their Japanese ancestry. She wrote about this experience in an autobiography entitled Desert Exile: The Uprooting of a Japanese American Family (1982), writing as an adult looking back upon her life, but in The Invisible Thread (1991), she writes for children, beginning with the time when she was a six-year-old until the time she was incarcerated during WWII. Thus, Yoshiko Uchida chose to write about her experiences for two separate audiences, and tailored her stories accordingly.

Similarly, in her fiction for children, the decision to speak through a child protagonist is clearly a conscious one. Although she was an adult when she was interned, in order to write for children about her experiences, she created the character of 11-year-old Yuki Sakane in Journey to Topaz (1971) and the follow-up book, Journey Home (1978). The story is told through the eyes of Yuki, the child protagonist.

Intended Audience: The Child Reader

There are, however, only a handful of autobiographies set in Singapore during WWII that are written specifically for children. These include Aishabee at War (1990) by Aisha Akbar, From Farm & Kampong (1989) by Dr Peter H.L. Wee, A Young Girl’s Wartime Diary (2007) by Si Hoe Sing Leng, Sunny Days of an Urchin (1996) by Edward Phua, and Papa as a Little Boy named Ah Khoon (2007) by Andrew Tan Chee Khoon.

Of these, Aishabee at War is arguably the most successful. It is a lively account of the author’s life between 1935 and 1945, filled with details that a child growing up into a teenager would note. On the one hand, her account is of a childhood much like any other. She writes, for instance, of her struggle to establish a place for herself as the youngest member of a large family, and how she found solace in reading and music. On the other hand, it is a fascinating account of a child living in unusual times. The details of history are woven into the fabric of the story, and revealed through the story, rather than through authorial intrusion.

Aisha Akbar shows an awareness of her intended child audience, stating in her preface that her autobiography “is a true account, as far as I can remember, of the events before the war, and up till 1945, as seen through the eyes of a child.”

She writes about the war in a factual, unsentimental way, sometimes finding humour even in dark situations. She recalls the somewhat surrealistic response of her neighbours to the bombing of Singapore:

A Young Girl’s Wartime Diary contains the diary entries of the writer from 1942 to 1945. However, as the writer chooses to arrange her entries thematically rather than chronologically, her account lacks narrative strength, and the reader has to piece together the overall picture of the events unfolding in the book. There is also a rather jarring shift in perspective from the adult authorial introduction to each section and the subsequent diary entries of the young author. Nevertheless, the book gives a genuine glimpse into the thoughts and feelings of a girl living in Singapore during the war.

Edward Phua’s Sunny Days of an Urchin has a stronger narrative. Although the style of writing is not as elegant as in Aishabee at War, the book is peppered with interesting details of the author’s childhood. His account testifies to the sheer ingenuity shown by his family members in creating ways to cope with the shortages of food and basic necessities during the war. This included devising ways to grow padi in their backyard and to harvest the rice.

Similarly, Peter Wee’s From Farm & Kampong testifies to the resilience shown by the local population in coping with the sudden changes to their lifestyles. Wee speaks appreciatively of his father’s readiness to buckle down to farm work:

For the whole family, life soon changed from the “cultured, middle-class and English-educated urban ways” to the “harsh exigencies of farm life” (p. 23). However, Wee also notes that their farm life did have its own rewards: He and his brothers soon became much more acquainted with nature (p. 25).

Wee has thoughtfully included black-and-white drawings of the two villages he lived in which are especially helpful as one of the villages no longer exists, while the other has changed substantially.

Similarly, Papa As a Little Boy Named Ah Khoon includes black-and-white illustrations which help the reader of today to bridge the gap between the Singapore of the 1940s and 1950s and the Singapore of today. As in Wee’s book, the war occupies the first part of Andrew Tan’s book, which is a record of the author’s childhood from 1943 to 1953.

The Lack of Fiction

While there are a handful of noteworthy autobiographies for children set during the war, there does not seem to be any book of fiction. The closest example would be the fictionalised biography, Son of an Immigrant (2007) by Joan Yap, which is based on the real-life story of a barrister, Lui Boon Poh. However, the part set during the war takes place in Batu Pahat, in then Malaya. The story shifts to Singapore only when the narrator, Ah Di, leaves Batu Pahat to find work in Singapore. It is an inspiring story about having the courage to pursue one’s dreams, with the war setting only occupying six of its 28 chapters.

While the book would have benefited from better editing, as there are numerous grammatical errors in the book, overall Joan Yap has done an admirable job of trying to “bridge the sobriety of history with the fun of fiction”.

Indeed, the marriage of both history and fiction is an area with much potential for exploration in storybooks for children in Singapore.

Conclusion

One of the obvious conclusions that can be drawn is that while some efforts have made to capture true experiences during WWII in autobiographies for children, little effort has been made to write children’s fiction set during this period. Similarly, little effort has been made to cater to the young child, as the books were written for children with fairly good reading stamina. It is hoped that with time, greater effort will be made to write fiction for children depicting this period of history, as well as other significant periods in the history of this region. Well-known Singapore writers like Lee Tzu Pheng and Edwin Thumboo have noted that there is a need for more support for Singaporean Literature in English. The need is not just for suitably talented Singaporeans to write literature for Singaporeans, but also for other Singaporeans to read their efforts, so as to bring about “a literature of our own of such quality and significance that we regard it as a substantial part of our national identity” (Lee, T.P., as cited in National Library, 2005b, p. 2). The need for a national literature was eloquently expressed by Margaret Atwood in 1972 in Survival: A Thematic Guide to Canadian Literature:

She also warned that if “a country of a culture lacks such mirrors it has no way of knowing what it looks like; it must travel blind” (p. 16). We need our own literature, too, so that we may navigate this significant period of history, that we may better understand how and why those “few years generated racial tensions, poverty, corruption and a whole host of social evils” while at the same time serving as an eye-opener, as “the Japanese Occupation helped Singapore’s migrants to define the meaning of ‘home’” (Lee G.B., 2005, p. 333). Good fiction for children set during this period will not only help fill the void in this area, but will also go some way in helping to build up the corpus of Singaporean literature for children in English.

The author wishes to acknowledge the contributions of Dr Sandra Williams, Senior Lecturer, School of Education, University of Brighton, in reviewing the paper.

Lee Kong Chian Research Fellow

National Library

REFERENCES

Aisha Akbar, Aisha Bee at War: A Very Frank Memoir (Singapore: Landmark Books, 1990). (Call no. RSING 959.57022 AIS)

Andrew Tan Chee Khoon, Papa As a Little Boy Named Ah Khoon (Singapore: Ring of Light Publishers, 2007). (Call no. RSING 959.5704092 TAN)

Ang Seow Leng et al., Asian Renaissance: The Singapore and Southeast Asian & Asian Children’s Collection Guide (Singapore: National Library Board, Publishing & Research Services, 2005). (Call no. RSING 025.21095957 ASS)

Anne Frank, The Diary of a Young Girl, trans. Susan Massotty (London: Penguin Books, 1997)

Diana Wong, ed., “Introduction,” in War and Memory in Malaysia and Singapore, ed. P. Lim Pui Huen and Diana Wong (Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, 2000), 1–8. (Call no. RSING 959.503 WAR)

Edward Phua, Sunny Days of an Urchin (Singapore: Federal Publications, 1996). (Call no. RSING 959.5704 PHU)

Fauziah Hassan et al., Singapore Children’s Literature: An Annotated Bibliography (Singapore: National Library Board, 2005). (Call no. RAC 015.5957 SIN)

Geoffrey Tan, Escape From Battambang: A Personal WWII Experience (Singapore: Armour Publishing, 2001). (Call no. RSING 940.54815957 TAN)

Harriet Ziefert, A New Coat for Anna (New York: Dragonfly Books, 1986). (Call no. ZIE)

Ian Serraillier, The Silver Sword (London: Heinemann Educational Books, 1957). (Original work published 1956)

James Riordan, Escape From War (London: Kingfisher, 2005)

Jerry Kerr, When Hitler Stole Pink Rabbit (London: Collins, 1998). (Original work published 1971)

Joan Yap, Son of an Immigrant (Singapore: Joan Yap, 2007). (Call no. YAP)

Johanna Reiss, The Upstairs Room (England: Puffin Books, 1979). (Original work published 1972)

Lee Geok Boi, The Syonan Years: Singapore Under Japanese Rule 1942–1945 (Singapore: National Archives of Singapore and Epigram, 2005). (Call no. RSING q940.53957 LEE)

Lois Lowry, Number the Stars (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Co., 1989). (Call no. J LOW)

Maisie Duncan, A Cloistered War: Behind the Convent Walls During the Japanese Occupation (Singapore: Times Editions, 2004). (Call no. RSING 940.5425092 DUN)

Margaret Atwood, Survival: A Thematic Guide to Canadian Literature (Toronto: Anansi, 1972)

Michael Morpurgo, Friend or Foe (London: Egmont Books, 2001). (Original work published 1977)

Michael Morpugo, Waiting for Anya (London: Egmont Books, 2001). (Original work published 1990)

Patricia Lim Pui Huen, “Memoirs of War in Malaya,” in Malaya and Singapore During the Japanese Occupation, ed. Paul H. Kratoska (Singapore: Journal of Southeast Asian Studies, 1995). (Call no. RSING 940.5425 MAL)

Patricia Polacco, The Butterfly (New York: Philomel Books, 2000)

Peter H.L. Wee, From Farm & Kampong (Singapore: Graham Brash, 1989). (Call no. RSING 959.57 WEE)

Rosalind Sharbanee Meyer, Rosie’s War: Escape From Singapore 1942 (NSW: Sydney Jewish Museum, 2007). (Call no. RSING 959.5704092 SHA)

Rudy Mosbergen, In the Grip of a Crisis: The Experiences of a Teenager During the Japanese Occupation of Singapore, 1942–45 (Singapore: Printed by Seng City Trading, 2007). (Call no. RSING 940.54815957 MOS)

Sheila Allan, Diary of a Girl in Changi, 1941–1945, 3rd ed (N.S.W.: Kangaroo Press, 2004). (Call no. RSING 940.547252092 ALL)

Si Hoe Sing Leng, A Young Girl’s Wartime Diary: The Journal of a Teenager Written During the Japanese Occupation of Singapore (Singapore: Lingzi Media, 2007). (Call no. RSING 959.5703 SIT)

Wang Gungwu, “Memories of War: World War II in Asia,” in War and Memory in Malaysia and Singapore, ed. P. Lim Pui Huen and Diana Wong (Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, 2000), 11–22. (Call no. RSING 959.503 WAR)

Yankev Glatshteyn, Emil and Karl, trans. Jeffrey Shandler (Connecticut: Roaring Book Press, 2006). (Original work published in Yiddish 1940)

Yoshiko Uchida, Journey to Topaz: A Story of the Japanese-American Evacuation (Berkeley, California: Heyday Books, 1971)

Yoshiko Uchida, Journey Home (New York: Aladdin Paperbacks, 1978)

Yoshiko Uchida, Desert Exile (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1982)

Yoshiko Uchida, The Invisible Thread (New York: Beechtree, 1991)