Women and Warfare in Malaysia and Singapore, 1941–89

Lee Kong Chian Research Fellow Mahani Awang explores the involvement of women in warfare in Malaya and Singapore from 1941 until the 1989 Hat Yai Peace Accord. She also considers how women differ from men in various activities connected to war.

Introduction

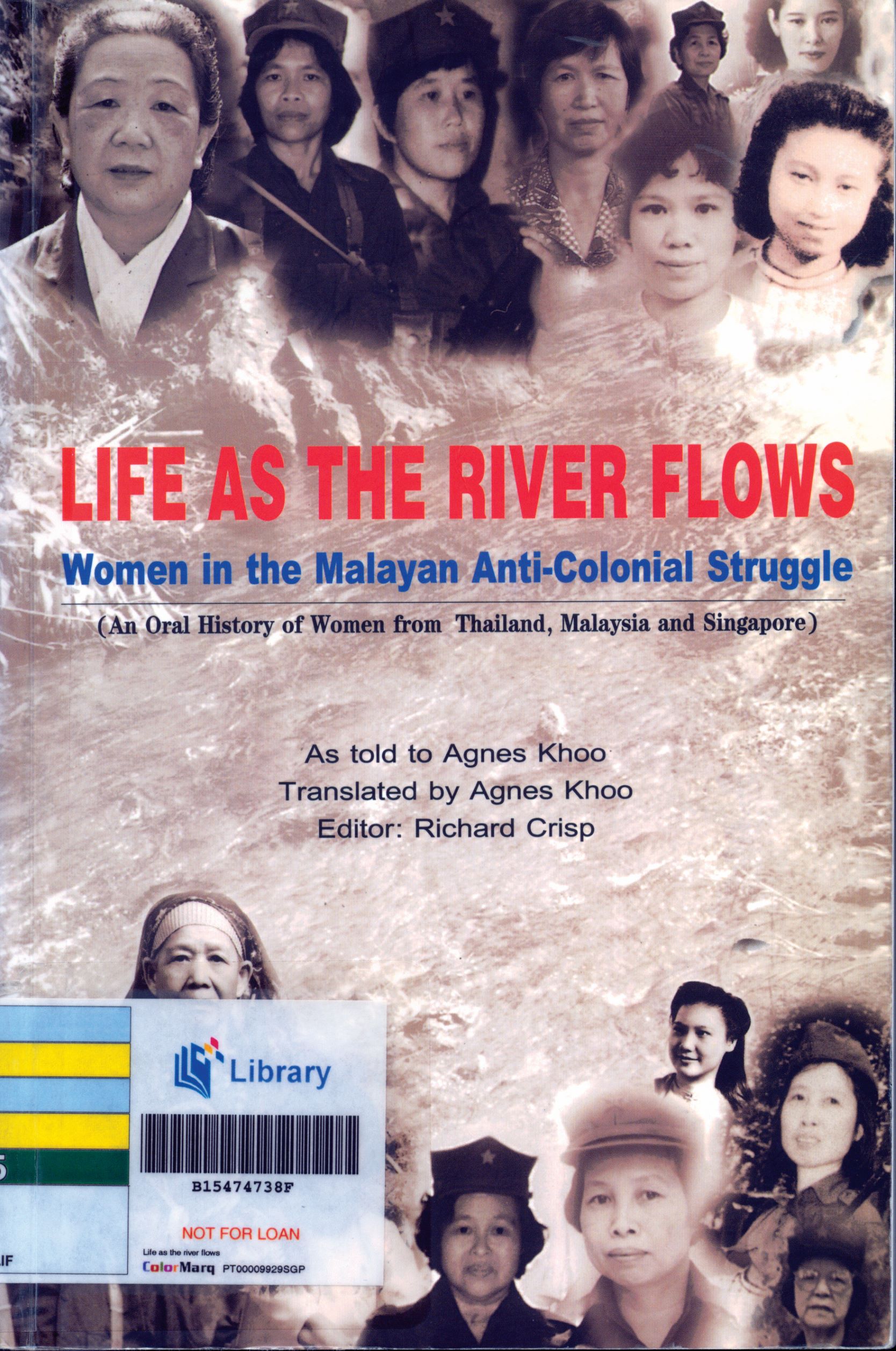

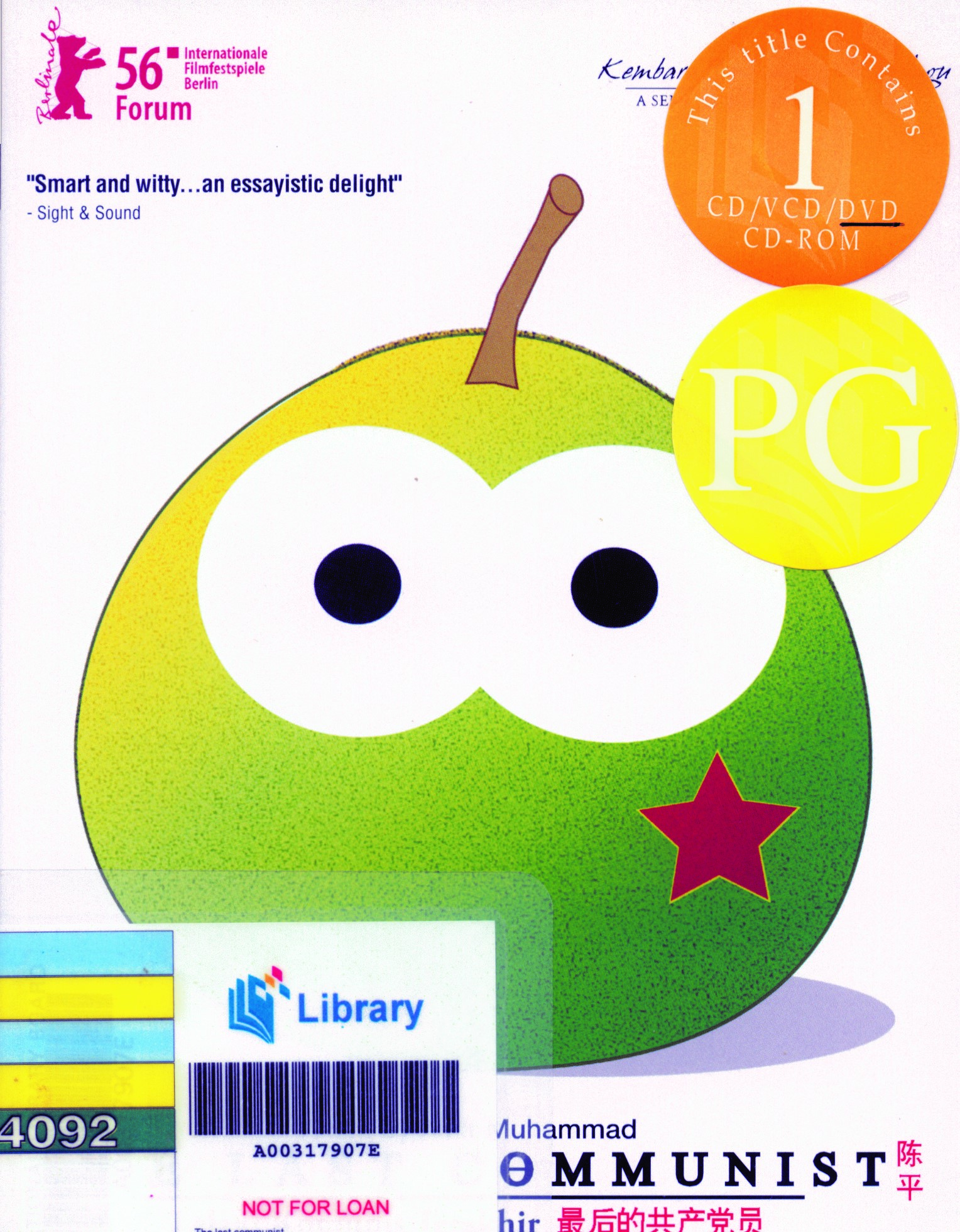

Much has been written about warfare – conquest and revolution, heroes and enemies. Yet women’s experience in warfare remains an uncharted area in Southeast Asian history. The paucity of records was partly rooted in patriarchal bias and ignorance on the part of historians when constructing new “autonomous” national histories after independence which sidelined those (including women) who did not fit into the new emerging national narratives, and was often cited as the main reason for this unfavourable situation. This led to misconceptions about women’s involvement in war. In the case of the Vietnam war, women soldiers remained invisible to most Americans and to the public gaze despite their contributions to the war and despite being an important facet of the most photographed war in history. With regard to Malaya (including Singapore before their separation in 1965), the groundbreaking study on former Malayan Communist Party (MCP) women guerillas by Agnes Khoo (2004) in Life As the River Flows remains unchallenged, although there were efforts to compile stories on the life of former guerillas through video documentary.

This paper explores the involvement of women in warfare in Malaya and Singapore (also in southern Thailand after the relocation of the MCP to the Malaya-Thai border in 1953) since 1941 until the 1989 Hat Yai Peace Accord. Using both historical method and gender as analytical tools, the study attempts to see how women differ from men in various activities connected to war.

Myriad Facets of Women in War

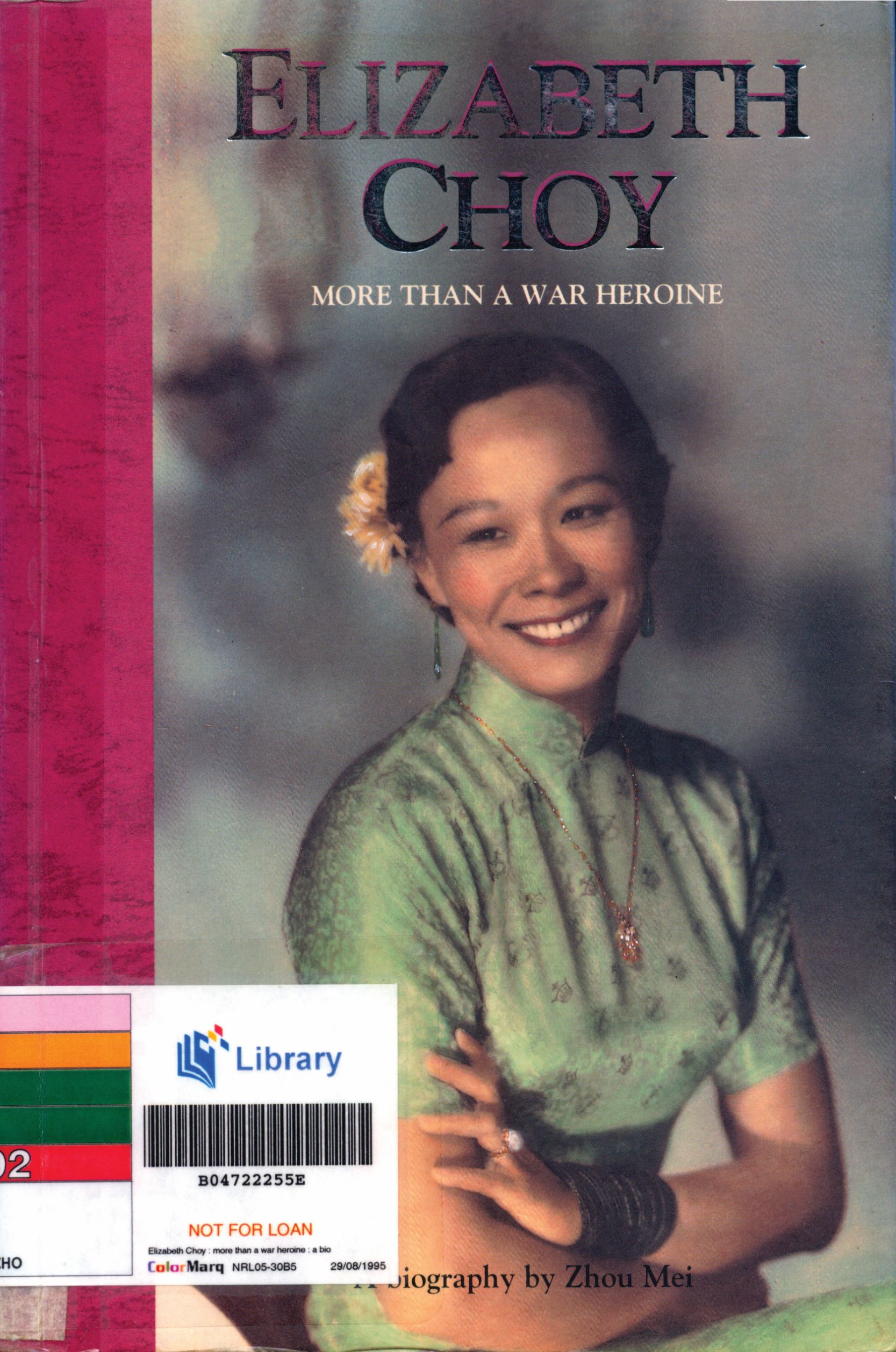

History has shown the involvement of women in war in a myriad facets ranging from warriors, fighters and spies to women as wives, daughters, lovers and war victims (including internees). In Southeast Asia, the Japanese Occupation during World War II saw women entering the war zone as fighters, internees and war victims and some were involved indirectly by providing various assistance to the anti-Japanese guerillas without their entry into the war zone, such as in the case of two famous war heroines of Malaya and Singapore – Sybil Kathigasu and Elizabeth Choy.1 Across Asia more than 100,000 women became victims of enforced prostitution known as “comfort women”; it took more than half a century after the war had ended for the victims to come forward and reveal their painful past (Hicks, 1995).2 Following the fall of Singapore, there were 2,800 civilian (mostly Europeans) internees at Changi prison; out of this, 430 were women and the number increased to 700 the following year. This number was actually small compared with the 7,000 women and children and 35,000 men interned in prison camps in Indonesia. Leaving the memory of pampered life behind, these internees lived under very harsh conditions – women and children were separated from their loved ones (except those interned in mixed family camps). They were no strangers to hunger, diseases, lack of medical supplies and a stressful life that resulted in recurring and sometimes violent bouts of despair and melancholy, with a few having gone mad and committed suicide (Allan, 2004).

Despite the negative impact the war had on their lives, recent research on the “forgotten” or relatively neglected captives of war found that the lives of women and children internees in mixed family camps as “full of energy, industry, creativity, fun and freedom” (Archer, 2008). The women organised birthday parties, schools, cooking lessons, concerts, sports, dances, religious sessions as well as singing and music which helped sustain them while in captivity (Colijn, 1995). The women internees in the Changi prison even published a camp newspaper called POW WOW which appeared from 1 April 1942 to 15 October 1943 (Michiko, 2008). Researchers believed internment had totally changed the women’s attitude towards life: from always depending on others to becoming more independent, strong and capable. Their life seemed much better than those of the offspring of Japanese-Indisch.3 The mothers of these children insisted on covering up the Japanese origin of their children by “deliberately silencing and hiding it” as they could not endure the shame and fear of societal rejection for engaging in a relationship with the enemy (Buccheim, 2008). As a result, these mothers took their secret to the grave.

Overall, Malayan women, irrespective of their background, race or religion, suffered and endured dire hardship during the Japanese Occupation in 1942–45. Rapes took place before the eyes of their own family. Many survived the ordeal by disguising themselves as men and smearing their faces with mud and charcoal to make themselves unattractive to the Japanese soldiers (Sybil, 1983).

Women Guerillas

Since time immemorial, war with its masculine nature, has been defined as a male activity, while the culturally female biology of women and motherhood means women do not take part in war. The exclusion of women from war and organised violence was a result of the general exclusion of women from the formal societal apparatus of power and coercion and their involvement in motherhood (Pierson, 1987). This polarisation subsequently creates gender differences – with war and public domain being a male preserve, while the women became a natural symbol for peace, the home and the protected society (Macdonald, 1987).

However, besides being war victims, women did not distance themselves from the resistance movement in their locality. In the 1940s and 1950s, the call for revolution issued by both the Hukbalahap guerillas in Luzon and the Viet Minh in North Vietnam, for instance, saw many women entering the war zone. In Malaya and Singapore, the signing of the Hat Yai Peace Accord in 1989 between the Malaysian government and the MCP which ended the 40-year guerilla war for the first time brought to the surface the story of women involvement in underground activities and the guerilla war. Subsequently, most of them settled in the four peace villages in southern Thailand which was opened by courtesy of the Thai government. Sixteen of the women were interviewed by Agnes Khoo and became the main sources for Life As the River Flows. Khoo concludes that women, from different educational and social backgrounds joined the movement as “a form of rebellion against feudalistic, patriarchal oppression they experienced as young women” (Khoo, 2004).

Unknown to Khoo, many women had joined or followed their husbands, friends, relatives or lovers to join the guerillas without themselves having any understanding of the communist objectives/ ideologies, but who nevertheless were impressed with the MCP leaders who always harped on British bias and discrimination against the poor and women. Some of them, especially those who had joined after the MCP relocated to the Malaysia-Thai border in 1953 (referred here as the second generation), did so due to poverty; they believed life would be much better if they joined the guerillas because everything was provided for. After the relocation, which was made due to security reasons, access to food sources, which was the major problem for the MCP guerillas during the Emergency, had improved considerably because there was support from the local villagers (Ibrahim Chik, 2004). Undoubtedly, some were coerced to do so (Xiulan, 1983). There were cases in which women were kidnapped and taken to the jungle, such as the case of the 84-year-old Rosimah Alang bin Mat Yen from Kampong Gajah, Perak. Rosimah had spent 52 years of her life living with the communists after she was kidnapped while working on the padi field in Changkat Jering in Manjong, Perak, at the age of 17 (Utusan Melayu, 30 May 2009)

The understanding of communist ideology and military struggle was more discernible among the first batch of women guerillas (those who had joined before the MCP withdrawal to southern Thailand) who were born during the British colonial period and had witnessed the colonial domination in Malaya. The earliest involvement of Malayan women in the anticolonial movement had taken place in the 1930s. The Japanese invasion of China in 1937 led the MCP to mobilise the Chinese regardless of gender into the anti-Japanese movement which became more organised during 1941–45. The women specially targeted were those with education; they were then subjected to the occasional communist propaganda (Suriani, 2006). Initially the Chinese women became underground members of the MCP or the Malayan People’s Anti-Japanese Army (MPAJA), acting as couriers, assisting the communists in their propaganda work, purchasing food for its armed forces and carrying out subversive activities. Chapman, during three-and-a-half years of living with the guerillas in the Malayan jungle as liaison officer with the MCP, dubbed the MPAJA girls as great fighters who were committed to fighting the Japanese and were never afraid to hold guns. He related one case: when the Japanese ambushed MCP leaders during a meeting near Kuala Lumpur; a girl emerged as an unlikely heroine firing at the Japanese with her tommygun to enable the men to escape until she was shot (Chapman, 1963). By the end of the Japanese Occupation, MCP propaganda had succeeded in bringing about the involvement of women into their armed forces and to continue the struggle against British colonial rule. Through educated Chinese women comrades, the MPAJA and MCP struggles extended to the Malay villages where the anti-Japanese sentiment was strong (Abdullah C.D., 2005).

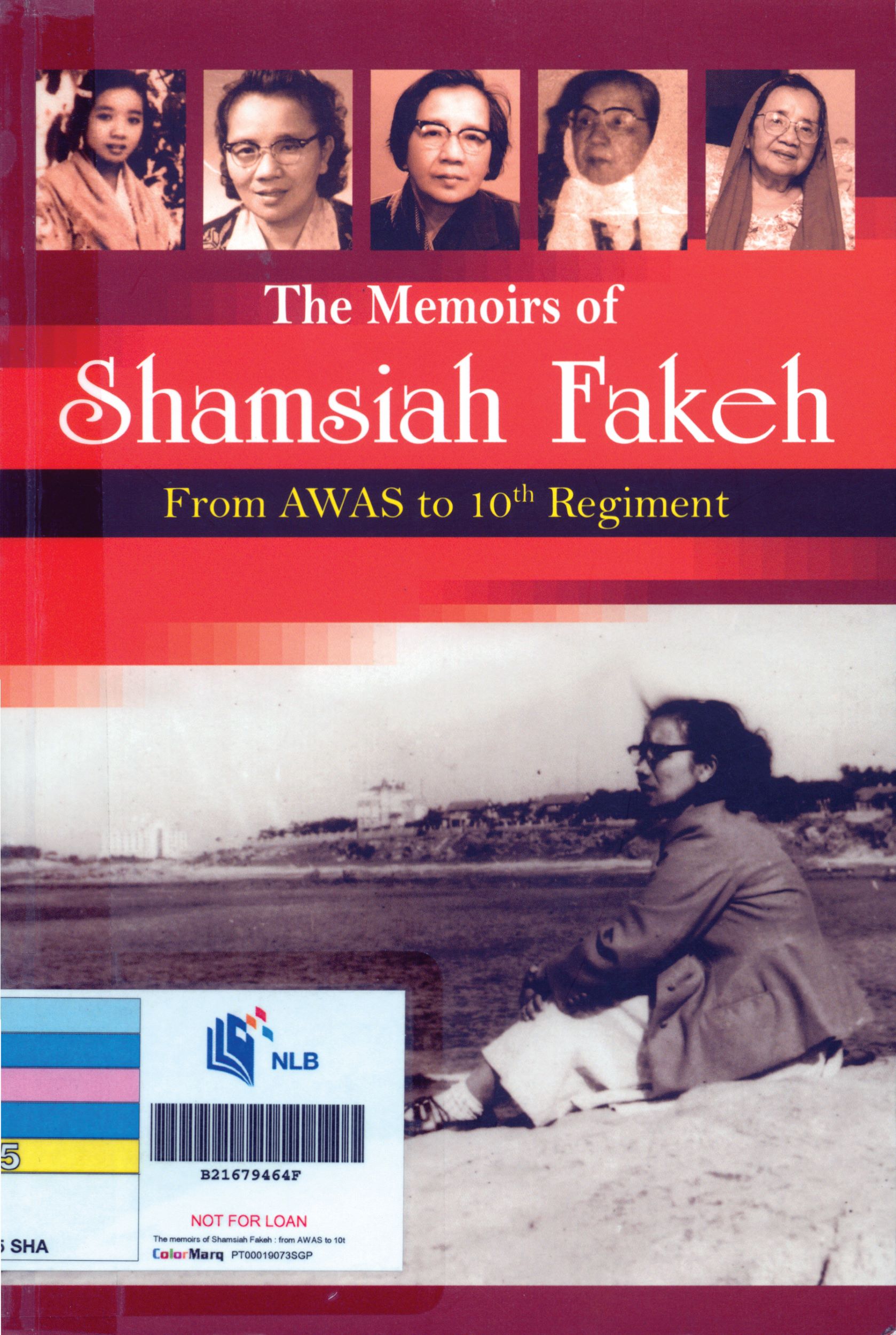

Compared with the Chinese community – which put kinship relations and friendship network above everything – that provided family members or close friends who had joined the guerilla movement with all kinds of support (Stubbs, 2004), the majority of Malays viewed Malay involvement in the radical movement as against Islam and many stayed away. Families that had members openly involved in such activities were often looked at with deep suspicion. In the end, many did secretly join the guerilla movement. Many Malay women who joined the guerilla movement were former members of the Angkatan Wanita Sedar (AWAS), the women wing of the Malay Nationalist Party (MNP). These women had their own philosophy and were pursuing aggressively the liberation of women from feudal oppression and negative social practices (Ahmad Boestamam, 2004). When the British banned all radical and leftist movements like MNP, Pembela Tanahair (PETA), Angkatan Pemuda Insaf (API) and AWAS in 1948, most of the radical Malays joined the MCP guerillas, including Shamsiah Fakeh and Zainab Mahmud, the leader and secretary of AWAS, respectively. This benefited the MCP enormously as these women were then widely accepted as “heroine” (srikandi) with their fluent and confident articulation, educational (religious) background, strong fighting spirit and unfazed by guns (Shamsiah, 2004).4

Women Comrades at Work

History has shown that each guerilla war has its own specific characteristics. However, a comparison among different guerilla wars shows that these wars do share some common traits. Like the Communist Party of the Philippines (CPP), female MCP cadres generally occupied a lower position in most of the military actions orchestrated by the party. Combat operations were normally handled by men and this became an impediment for women to climb to higher positions in the party hierarchy as combat experience was often taken into consideration for promotion (Hilsdon, 1995). The belief among female comrades that only those who were brave and intelligent could climb the ladder of success within the organisation was quite prevalent. This statement is quite true if we look at the “success” story of well known MCP women leaders like Shamsiah Fakeh and Suriani Abdullah or Eng Ming Ching before her marriage to Abdullah C. D., the commander of the Malay Regiment in the MCP – the 10th Regiment – in 1955. Starting as an MCP member in Ipoh in 1940, the urban-educated Suriani, who had fought for the liberation of Malaya (from the British) and also for the liberation of women, began the rapid climb in the MCP when she was entrusted to lead a propaganda team in Ipoh, and later in Singapore, and was directly responsible for the relocation of the 10th Regiment from Pahang to the Malaya-Thai border in 1953–54. The highest position Suriani had held was that of central committee member of the MCP (Suriani, 2006). Her charismatic way in handling the tasks and settling the problems given to her and her wide experience in wartime had led her to hold many important appointments within the MCP (Rashid Maidin, 2005). In other words, her marriage to the regimental commander was a mere coincidence. For Shamsiah, although it was not clear what her rank was within the MCP, her leadership was groomed by leaders of the 10th Regiment who were also former colleagues from the MNP, with the aim to attract more Malay women to join the movement (Dewan Masyarakat, August 1991).

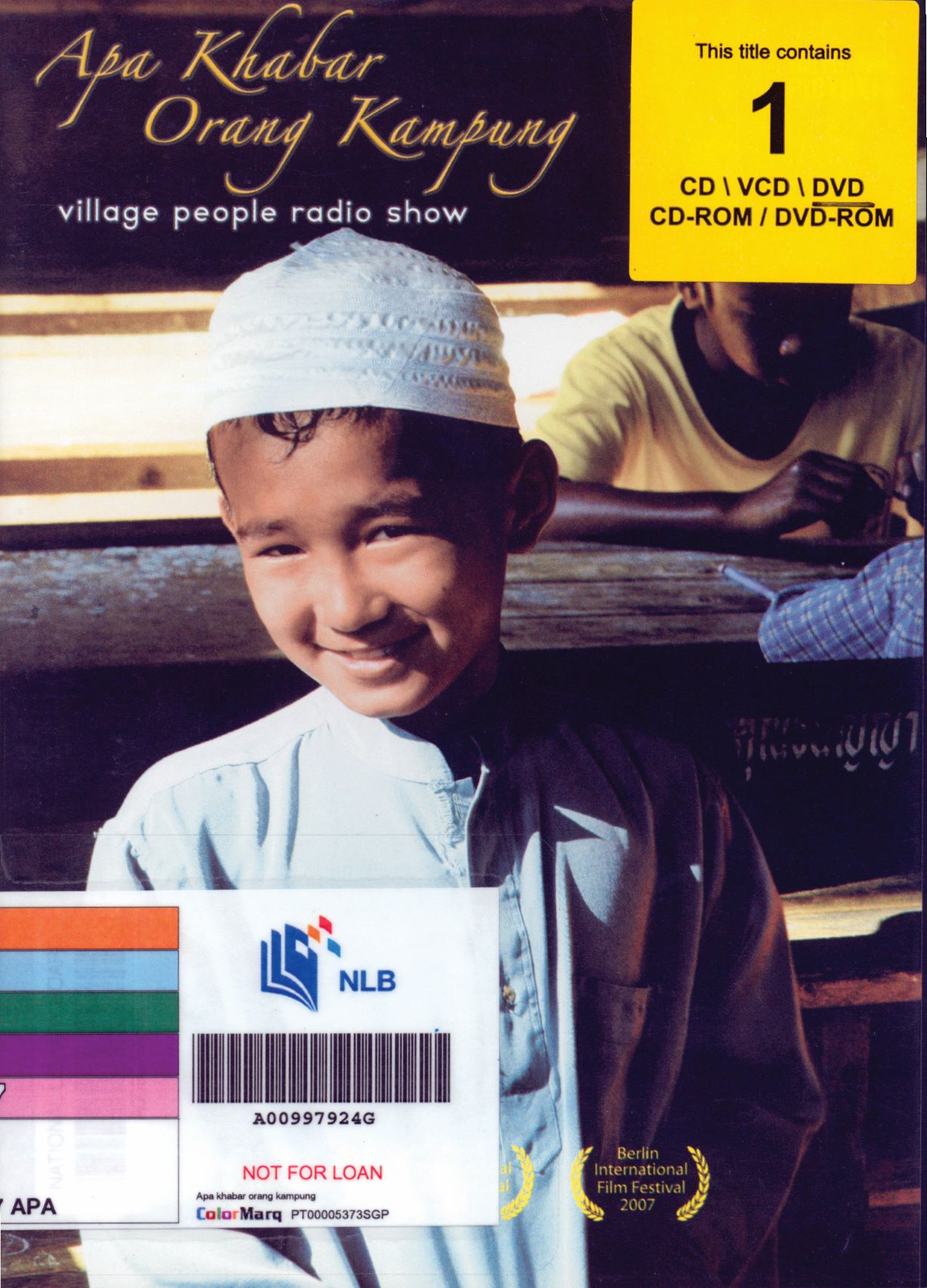

Before the MCP relocated to south Thailand, women comrades, although their exact number was not known, formed an important part of the fighting strength of the MCP, with a few heading platoons and fighting units. Interestingly, Abdullah C.D. (2007) viewed those women who had perished in the anti-colonial struggle as “Srikandi bangsa” (flowers of the nation), a label that was never accorded at the time by any other Malayan political movement to their women wing. They were also involved in the “long march” towards the Malaya-Thai border in 1953 which many MCP members dubbed the highest struggle when they had to march from one place to another through thick jungle and mountainous terrain, often at the risk of ambush by colonial forces, handicapped by shortage of arms, ammunition and food, and without the support of the Orang Asli and Chinese squatters who were moved to “New Villages” following the implementation of the “Briggs Plan” in 1950.5 The journey itself took a year and six months to complete (Apa khabar Orang Kampong / Village People Radio Show, 2007). For female comrades, they suffered more especially those who were pregnant, such as the case of Zainab Mahmud (Musa Ahmad’s wife)6 who was at an early stage of pregnancy when the long march began (Aloysius, 1995). During this testing period, all hygienic needs during birth or menstruation were secondary with jungle plants used widely to stop or delay this biological process while some women stopped menstruating due to the hardship. These plants were also used to facilitate abortion or to prevent hunger.7

Life in the Guerilla Camps

As stressed by Becket (1999), the word “guerilla” connotes war and wartime conditions in difficult terrains like mountain and jungle. Being well versed with the local environment provides mobility to the guerillas who favours “hit-and-run” tactics that would inflict damage. It also provides time and opportunity to evade the enemy. Guerillas also tend to enjoy local support, especially those living in the jungle, although at times this was secured through terror tactics which were a necessity so as to prolong the struggles (Beckett, 1999). This definition fits the nature of the MCP struggles. Its tactics of “attack and quick withdrawal” and “hide and survive” became the main feature of the MCP guerilla war which enabled it to survive until 1989. The MCP guerillas lacked both arms and food. Hunger and starvation were part of their lives and they also had to be constantly on the run and never camped for long in one place (Ibrahim Chik, 2004; Apa Khabar Orang Kampong, 2007).

Under this stressful and uncertain condition, both the MPAJA and MCP female guerillas lived their everyday life together with male comrades. During stressful times, such as the Japanese Occupation (1941–45) and the Emergency (1948–60) there was no clear boundaries or lines between gender especially during wartime as both male and female comrades had to combine their collective energy to ensure victory. Like the males, female combatants underwent a similarly difficult life; they had to abide by party discipline, undertake specific duties in the camps such as sentry duty, transporting food which many female comrades claimed as the most difficult task (Xiulan, 1983), cooking and nursing, besides attending military trainings and political courses. They were also exposed to offensive measures by Japanese intelligence apparatus and later British security forces and were liable to be killed if caught by the enemy as reported in the Straits Echo and Times of Malaya between the late 1940s and early 1950s.

Moving to urban guerilla warfare in Singapore (Singapore became the main base for propaganda work), the colonial response saw the arrests of many women including a Chinese woman who was responsible for directing all the MCP activities in Singapore (CO 1022/207). Many were also caught by the Singapore authority for their involvement in the “anti-yellow culture” campaign of the 1950s which saw the active involvement of the Singapore Women Federation (PRO 27 330/56). The campaign was directed against imported culture which corrupted the individual and public moral but was perceived by the colonial government as communist propaganda to raise political awareness in the intellectual class (Harper, 1999).

Even though their job seemed to be equal to that of the men’s, some of the former female guerillas claimed women were given comparatively easy tasks due to their physical built. Perhaps this refers to those from the second-generation combatants who saw fewer armed skirmishes and the women were given tasks such as sewing, breeding animals and nursing as well as tasks related to the kitchen; these job were less demanding whereas going to war was preferably given to men. Except for Chang Li Li, most of the women interviewed (most of them were from the second generation of MCP combatants) claimed they were never involved with any armed skirmishes and that women would be the last to be given weapon training compared with the men in their camp. They admitted the combination of bravery and intelligence would certainly enhance (in the eyes of their superior) the female cadres’ opportunity for success (namely, promotion) and to take part in military operations.

While war might break down gender boundaries especially during stressful times, and women were able to live in the hostile jungle, in reality, there was little to separate the women guerillas from womanhood or the emotion of motherhood. Of interest are their love life (to be in love and to be loved), marriage, procreation and children. Each camp conducted its everyday life in accordance with its own rules. Interestingly, while the Communist Party of the Philippines’ (CPP) practised a more liberal policy on sexual matters which created problem to the movement by allowing marriage and, in the end, many female CPP were engrossed in looking after their family while war became the responsibility of the men (Hilsdon, 1995), the MCP seemed to have a stricter general policy about family life within the camp although, towards the end of the struggle, this policy became more lenient. Marriage was allowed in most MCP camps but during the Japanese Occupation, husband and wife were not allowed to work in the same camp to avoid sexual complications. As reported by Force 136 (during the liaison with the MPAJA), these matters were unheard of during their war against the Japanese (Chin & Hack, 2004). This complication became common during the Emergency and thereafter with certain camps putting up a strict policy with regards to love, marriage and pregnancy. The 8th Regiment in Natawee district, for instance, prohibited its women cadres to be pregnant; if found to be so, they were forced to have an abortion.

As the hostile jungle and wartime conditions were not suitable for raising children, most camps had in place a rule of giving away babies to local villagers. Again female cadres had to face enormous emotional struggles to part with their loved ones. Although some interviewed women tried to hide their real feelings at the time of their involvement with the guerillas by saying they did not regret what they had gone through, there were women who refused to think or remember their life in the jungle, especially when asked about the separation with their children. Others simply could not resist motherhood and managed to escape from the camp. 68-year-old Khatijah, who was interviewed in March 2009 in Betong, southern Thailand, claimed many women had to endure sadness upon leaving their family behind but did not have the courage to leave camp for fear of possible punishment by the MCP. Some felt miserable at the time of separation with their babies but relented as the safety of the children became their main concern (I Love Malaya, 2006). The most tragic incident befell Shamsiah Fakeh when she was accused of killing her own baby in the jungle, an accusation, which she claimed was meant to smear her reputation, that she had repeatedly refuted in her memoir. In the memoir, she asked her readers “as a nationalist fighter, could a mother kill her own child?” (Shamsiah, 2004, p. 72).

The accusation of killing her son (in the case of Shamsiah Fakeh) is probably the only case of its kind in the history of female guerillas in the MCP. But the problem of illicit sex, which led to unwanted pregnancy, was nothing new in guerilla life. Sometimes it also involved leaders of the movement, which led to morale decline in the party. Some party members regarded illicit love affairs as a serious problem that started when the MCP tried to strengthen the party after the withdrawal to southern Thailand by “accepting newcomers” (men and women) to the party, mostly local Thais. As there was no clear method to control recruitment, the MCP failed to differentiate the “good guys” from the “bad guys”. There were also members who believed women were manipulated as a tool to sabotage the MCP; these women were sent to create havoc by using illicit love affairs to ensure that leaders were engrossed in this distraction to the detriment of the political struggle and ideological purity (Ibrahim Chik, 2004, p. 202). Besides the issue of intimate relationship, MCP members also claimed the enemy (Thai government) used women to poison their leaders through food as women were in control of the kitchen. There were many cases of sabotage by poisoning which were highlighted in the memoirs of MCP leaders.8

Spies (including women spies) who had infiltrated the MCP had caused considerable chaos among party members at the end of the 1960s. In its effort to eliminate sabotage, the MCP conducted a rectification campaign to identify and capture spies. Orchestrating these efforts were a few leading figures of the North Malaya Bureau, including a female leader by the name of Ah Yen who admitted to using torture to get the truth from those arrested. This campaign saw many women caught and punished on suspicion of being spies (Bei Ma Ju Po Huo Di Jian Zheng Xiang, 1999). In 1968, the rectification campaign in the 12th Regiment saw 35 members massacred, 200 others “exposed and criticised” and another 70 sacked from the party. The same drive was targeted at the 8th Regiment.

The drive to capture spies in the MCP created cracks in the movement as some camp leaders claimed many combatants had become victims of unproven accusations. The rectification campaign, which affected every new recruit and later the veterans, brought about a major split in the MCP into factions, including the MCP central faction, 12th Regiment breakaway faction, the MCP (Marxist-Leninist) faction which was formed in August 1974 and the MCP revolutionary faction (formerly the 8th Regiment).

Conclusion

From the discussion, women do have their own “space” in war history whether as fighters, spies, wives, daughters and war victims. In the case of the guerilla movements in Malaya/Malaysia and Singapore, while the war broke down the boundaries between men and women as they had to fight for survival and victory, womanhood was never totally suppressed from the female comrades. To be in love and to be loved often ended in unwanted pregnancies, the sadness of being detached from motherhood as they were not allowed to raise children in the camps, and missing out on the “outside world”, which led many to escape, were among the issues that had appeared within camp life in the jungle. This perspective offers a new insight with regard to women involvement in the guerilla movement in Malaya, and is different from Khoo’s Life As the River Flows which is more concerned with the “voices” of these women collected through interviews without in-depth analysis.

The author wishes to thank Dr Cheah Boon Kheng, Honorary Editor, Journal of Malaysian Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society, for his constructive comments on an earlier draft of the paper.

Lee Kong Chian Research Fellow

National Library

REFERENCES

Primary Sources

Political Situation Reports From Singapore (Secret). CO 1022/206.

Political Situation Reports From Singapore (Secret). CO 1022/207.

Monthly Emergency and Political Reports on the Federation of Malaya and Singapore Prepared by S.E.A Department (Secret). CO 1022/208.

Anti-Yellow Campaign (Confidential). PRO 27 330/56.

Books and Articles

Abdullah C.D., Memoir Abdullah C. D.: Zaman Pergerakan Sehingga 1948, vol. 1 (Petaling Jaya: Strategic Information Research Development, 2005). (Call no. R 959.503 ABD)

Abdullah C.D., Memoir Abdullah C. D: Penaja Dan Pemimpin Rejimen Ke-10, part 2 (Petaling Jaya: SIRD, 2007)

Adrianna Tan, “The Forgotten Women Warriors of the Malayan Communist Party,” IIAS Newsletter, no. 48 (Summer 2008), https://www.iias.asia/sites/iias/files/nwl_article/2019-05/IIAS_NL48_1213.pdf

Agnes Khoo, Life As the River Flows: Women in the Malayan Anticolonial Struggle (Petaling Jaya: SIRD, 2004). (Call no. RSING 959.5105 LIF)

Ahmad Boestamam, Memoir Ahmad Boestamam: Merdeka Dengan Darah Dalam API (Bangi: Penerbit Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia, 2004). (Call no. RSEA 959.50923 AHM)

Akashi Yoji and Yoshimura Mako, eds., New Perspectives on the Japanese Occupation in Malaya and Singapore, 1941–1945 (Singapore: National University Press, 2008). (Call no. RSING 940.5337 NEW)

Aloysius Chin, The Communist Party of Malaya: The Inside Story (Kuala Lumpur: Vinpress, 1995). (Call no. RSING 959.51 CHI)

Anne-Marie Hilsdon, Madonnas and Martyrs: Militarism and Violence in the Philippines (Australia: Allen & Unwin, 1995). (Call no. RSEA 305.409599 HIL)

Anthony Short, The Communist Insurrection in Malaya 1948–60 (London: Frederick Muller, 1975). (Call no. RSING 959.5104 SHO)

Bei Ma Ju Po Huo Di Jian Zheng Xiang [The truth behind the detention of spies by the Northern Peninsular Department] (Thailand: The Committee of Kao Nam Khang Historical Tunnel, Sadao, 1999)

Bernice Archer, “Internee Voices: Women and Children’s Experience of Being Japanese Captives,” in Forgotten Captives in Japanese-Occupied Asia, ed. Karl Hack and Kevin Blackburn (London: Routledge, 2008), 224–42. (Call no. RSING 940.547252095 FOR)

C.C. Chin and Karl Hack, eds., Dialogue With Chin Peng: New Light on the Malayan Communist Party (Singapore: Singapore University Press, 2004). (Call no. RSING 959.5104 DIA)

Cheah Boon Kheng, Red Star Over Malaya: Resistance and Social Conflict During and After the Japanese Occupation, 1941–1946 (Singapore: Singapore University Press, 1987). (Call no. RSING 959.5103 CHE)

Chin Peng, My Side of History As Told to Ian Ward & Norma Miraflor (Singapore: Media Masters, 2003). (Call no. RSING 959.5104092 CHI)

Evelyn Buchheim, “Hide and Seek: Children of Japanese-Indisch Parents,” in Forgotten Captives in Japanese-Occupied Asia, ed. Karl Hack and Kevin Blackburn (London: Routledge, 2008), 260–77. (Call no. RSING 940.547252095 FOR)

F. Spencer Chapman, The Jungle Is Neutral (London: Chatto & Windus, 1963). (Call no. RCLOS 940.53595 CHA)

F. W. Beckett, Encyclopedia of Guerrilla Warfare (Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO, Inc., 1999)

George Hicks, The Comfort Women: Sex Slaves of the Japanese Imperial Forces (Singapore: Heinemann Asia, 1995). (Call no. RSING 364.138 HIC)

Helen Colijn, Song of Survival: Women Interned (Ashland: White Cloud Press, 1995). (Call no. RSING 940.547252 COL)

Ibrahim Chi, Memoir Ibrahim Chik: Dari API Ke Rejimen Ke-10 (Bangi: Penerbit Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia, 2004). (Call no. RSEA 355.0092 IBR)

Iskander Carey, Orang Asli: The Aboriginal Tribes of Peninsular Malaysia (Kuala Lumpur: Oxford University Press, 1976). (Call no. RCLOS 301.209595 CAR)

Jan Ruff-O’Herne, 50 Years of Silence (Sydney: Editions Tom Thompson, 1994). (Call no. R 364.153 RUF)

Karen Gottschang Turner with Phan Thanh Hao, Even the Women Must Fight: Memories of War From North Vietnam (New York: John Wiley & Sons, 1998). (Call no. RSEA 959.70430922 TUR)

Michiko Nakahara, “The Civilian Women’s Internment Camp in Singapore: The World of POW WOW,” in New Perspectives on the Japanese Occupation in Malaya and Singapore, 1941–1945 (Singapore: NUS Press, 2008) (Call no. RSING 940.5337 NEW)

Rashid Maidin, Memoir Rashid Maidin: Daripada Perjuangan Bersenjata Kepada Perdamaian (Petaling Jaya: Strategic Information Research Development, 2005). (Call no. R 323.04209595 RAS)

Richard Stubbs, Heart and Minds in Guerilla Warfare: The Malayan Emergency, 1948–1960 (Singapore: Eastern Universities Press, 2004). (Call no. RSING 959.504 STU)

Ruth Roach Pierson, “Did Your Mother Wear Army Boots?: Feminist Theory and Women’s Relation to War, Peace and Revolution,” in Images of Women in Peace and War: Cross-cultural and Historical Perspectives, ed. Sharon Macdonald and Peter Holden (London: Macmillan Education, 1987), 205–27.

Shamsiah Fakeh, Memoir Shamsiah Fakeh: Dari AWAS Ke Rejimen Ke-10 (Bangi: Penerbit Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia, 2004). (Call no. RSEA 923.2595 SHA)

Sharon Macdonald, “Drawing the Lines – Gender, Peace and War: An Introduction,” in Images of Women in Peace and War: Cross-cultural and Historical Perspectives, ed. Sharon Macdonald and Peter Holden (London: Macmillan Education, 1987)

Sheila Allan, Diary of a Girl in Changi, 1941–1945, 3rd ed. (New South Wales: Kangaroo Press, 2004). (Call no. RSING 940.547252092 ALL)

Shirley Fenton Huie, The Forgotten Ones: Women and Children Under Nippon (N.S.W.: Angus & Robertson Publishers, 1992). (Call no. RSEA 940.547252 HUI)

Suriani Abdullah, Memoir Suriani Abdullah: Setengah Abad Dalam Perjuangan (Petaling Jaya: Strategic Information Research Development (SIRD), 2006). (Call no. R 322.4209595 SUR)

Swee Lian, Tears of a Teenage Comfort Women (Singapore: Horizon Books, 2008). (Call no. RSING 940.5405092 SWE)

Sybil Kathigasu, No Dram of Mercy (Singapore: Oxford University Press, 1983). (Call no. RSEA 940.547252 KAT)

T. N. Harper, The End of Empire and the Making of Malaya (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999). (Call no. RSING 959.5105 HAR)

Xiulan, I Want To Live: A Personal Account of One Woman’s Futile Armed Struggle for the Reds (Petaling Jaya: Star Publications, 1983). (Call no. RU RCLOS 322.4209595 XIU)

Yuki Tanaka, “Introduction,” in Maria Rosa Henson, Comfort Women: A Filipina’s Story of Prostitution and Slavery Under the Japanese Military (Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 1999). (Call no. RSEA 940.5405092 HEN)

Zhou Mei, Elizabeth Choy: More Than a War Heroine (Singapore: Landmark Books, 1995). (Call no. RSING 371.10092 ZHO)

Newspapers & Magazines

Dewan Masyarakat (February–August, 1991). (Call no. RCLOS q059.9923 DM)

Straits Echo and Times of Malaya, 1949–1951

Utusan Malaysia (2009, May 30).

Videorecording/CD-ROM

Amir Muhammad, Apa Khabar Orang Kampong [Village people radio show], Objectifs Films, 2004, videorecording. (Call no. RAV 791.437 APA)

Amir Muhammd, The Last Commununist, Comstar Entertainment, 2006, videorecording. (Call no. RSEA 959.5104092)

Chan Kah Mei, et al., I Love Malaya, Objectifs Films, 2006, videorecording. (Call no. RSING 320.5320922595 I)

Interviews

Aishah @ Suti, personal communication, 7 January 1998.

A’Ling @ A’Yu, personal communication, 11 March 2009.

A’Por @ Wun Jun Yin, personal communication, 11 March 2009.

Chang Li Li, personal communication, 1 January 2009.

Khadijah Daud @ Mama, personal communication, 25 February 2009.

Leong Yee Seng @ Hamitt, personal communication, 14 March 2009.

Maimunah @ Khamsiah, personal communication, 25 February 2009.

Muna or Mek Pik, personal communication, 14 March 2009.

Shiu Yin, personal communication, 14 March 2009.

Ya Mai, personal communication, 1 January 2009.

NOTES

-

See, Sybil Kathigasu, No Dram of Mercy, intro. Richard Winstedt and Preface by Cheah Boon Kheng (Singapore: Oxford University Press, 1983) (From PublicationSG); Zhou Mei , Elizabeth Choy: More than A War Heroine (Singapore : Landmark Books, 1995). (Call no. RSING 371.10092 ZHO). Sybil and Elizabeth suffered direct physical and psychological torture in the hands of the Japanese kempeitai (military police). Sybil died in June 1949 due to the torture. ↩

-

The revelation was made through the publication of memoirs by victims. See, for instance, Maria Rosa Henson, Comfort Women: A Filipina’s Story of Prostitution and Slavery Under the Japanese Military (Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 1999). (Call no. RSEA 940.5405092 HEN); Swee Lian, Tears of a Teenage Comfort Women (Singapore: Horizon Books, 2008). (Call no. RSING 940.5405092 SWE); Jan Ruff-O’Herne, 50 Years of Silence (Sydney: Editions Tom Thompson, 1994). (Call no. R 364.153 RUF) ↩

-

‘Indisch’ denotes both Europeans and Eurasians who had settled in the Netherlands East Indies. They were born through the intimate relationship of their mothers with Japanese soldiers. ↩

-

This information was based on interviews with former female MCP guerillas now residing in Betong, southern Thailand, between January 2009 and March 2009. ↩

-

Iskander Carey, Orang Asli: The Aboriginal Tribes of Peninsular Malaysia (Kuala Lumpur: Oxford University Press, 1976), 311. (Call no. RCLOS 301.209595 CAR). It was reported that by 1953, 30,000 Orang Asli were already under communist influence. ↩

-

Musa Ahmad was one of the important leaders in the 10th Regiment. ↩

-

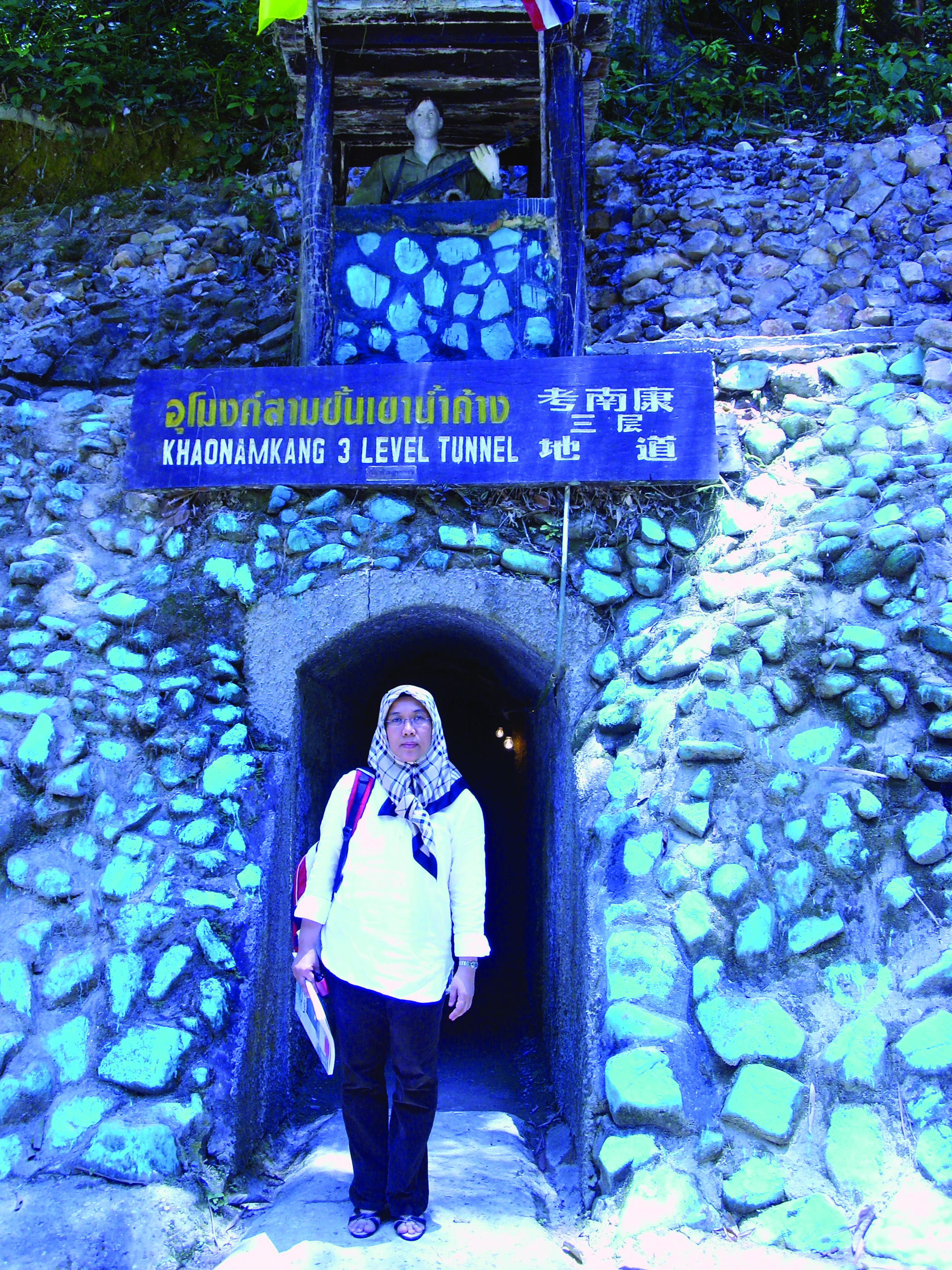

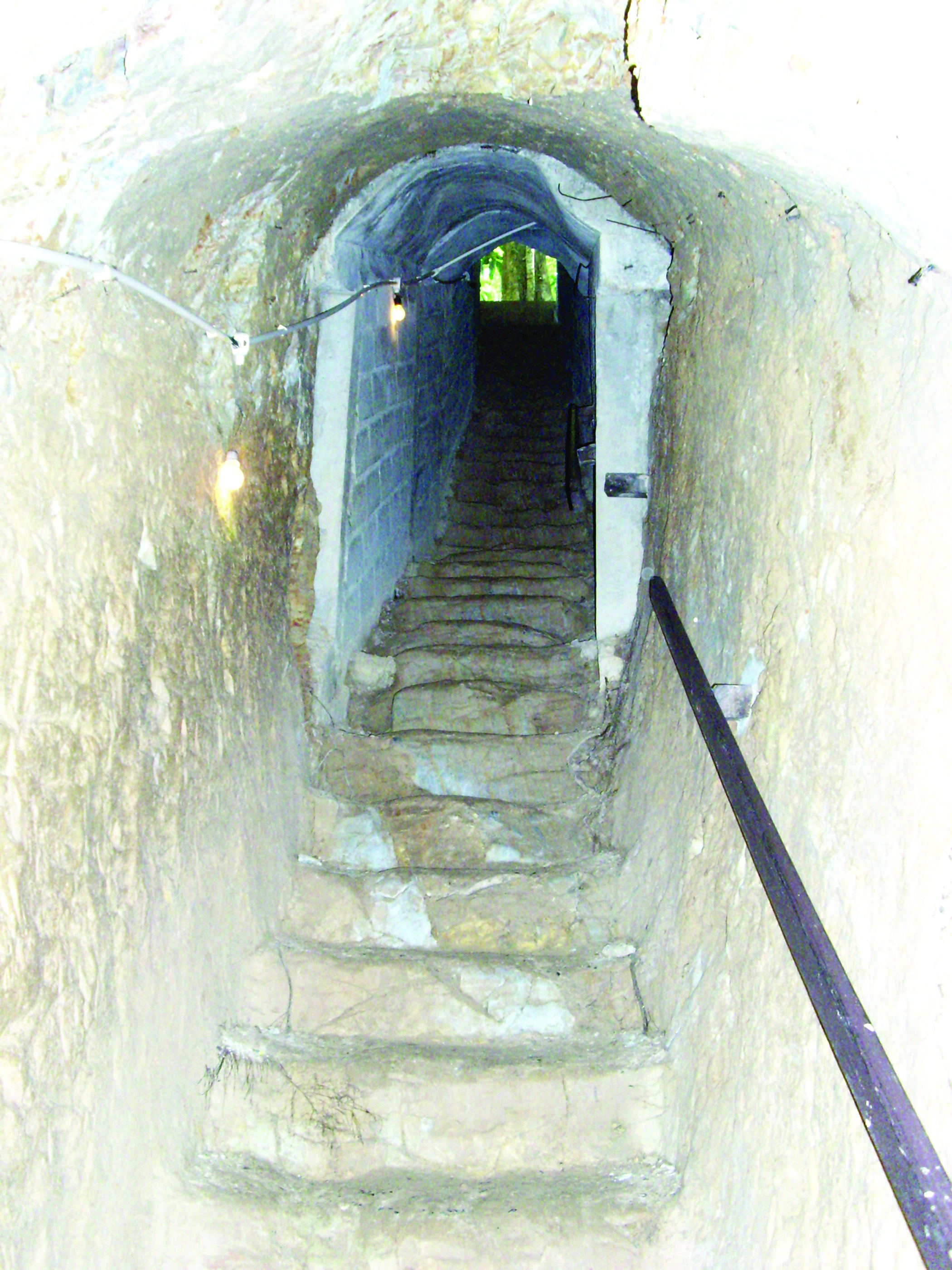

This information was provided by Leong Yee Seng, the former members of the 8th Regiment who managed the Khao Nam Khang Historical Tunnel in the Natawee District of Songkhla Province during an interview on 14 March 2009. The Khao Nam Khang Historical Tunnel was formerly a main base for the 8th Regiment. ↩

-

Ibrahim Chik, Abdullah C.D. and Suriani Abdullah were among MCP leaders who had first-hand experience of sabotage through poisoning. ↩