Childhood Memories: Growing Up in the 1950s and 60s

Lee Kong Chian Research Fellow Phyllis Ghim-Lian Chew recounts her childhood memories growing up in the 1950s and 60s.

As my research is on the sociolinguistics of early Singapore, I’ll introduce myself by recounting some childhood memories which have contributed to my historical bent and the languages that underlay it.

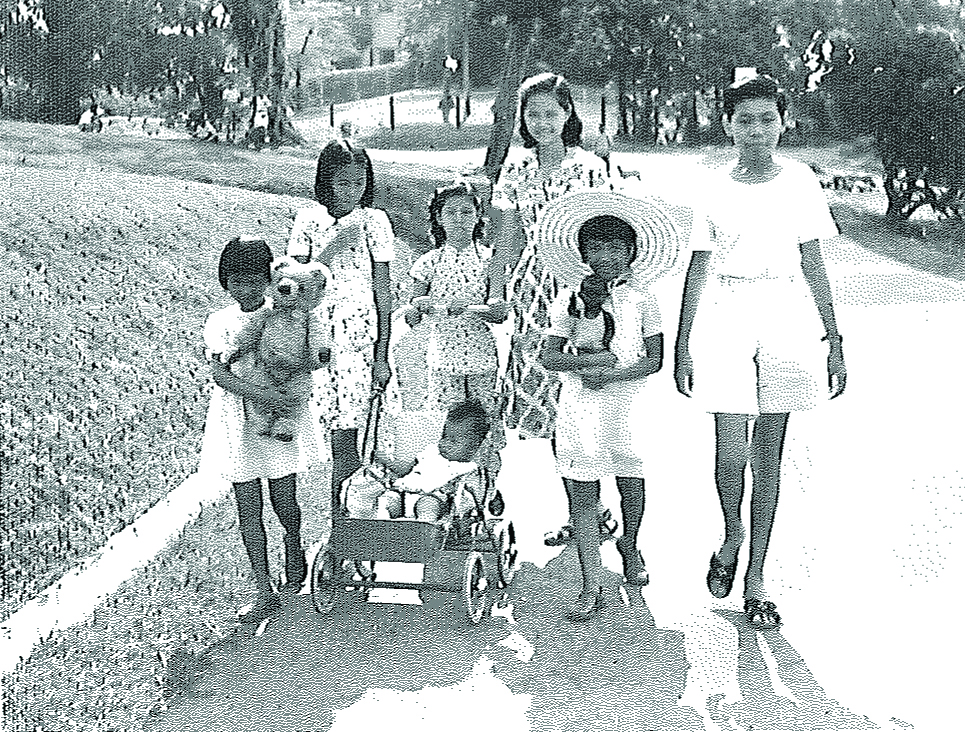

It is ironical that I should focus on languages for, as a child, I moved around more than I spoke. Instead of desk work, I would be playing marbles, gasing (Malay word for top), five stones and capteh (patois for shuttlecock). One morning at the age of nine, thinking I was Supergirl, I leapt from a kitchen window, but slipped as I landed, and saw twinkling stars upon reawakening. At 10, while exploring tombstone inscriptions behind the old National Library on Stamford Road, I tripped and rolled down Fort Canning slope, dislocating my elbow. In a game of “rounders” at 12, I broke my knee and was in a cast the rest of the year. The cast sent me to the library and I have been “hooked” ever since.

There were no casinos in Singapore then. I accompanied my mother Lee Poh Tin (1919–2008) on her rounds of mahjong with her Cantonese kaki (patois for friends) and cherki (Peranakan card game played with a pack of sixty) with her Peranakan relatives. It was the unspoken rule then that nurses were not to marry. Hence, my mother had to leave her job after marriage and turn instead to child-raising and other social activities common to married women of that era. I was immersed in their lively chatter and often futile but sometimes fruitful attempts at matchmaking. I became an expert in ordering noodles from the multilingual “tick-tock” hawkers, lowering the basket from the upper storeys down to the hawker at the five-foot way and raising it up again.

It was the custom for some families to assign the care of the child to a Cantonese maid and Ah Sun featured prominently in my baby photographs. However, she left shortly for the hairdressing trade just before I entered Primary One and I was assigned to the care of my maternal grandmother, Ang Lee Neo (1888–1962). Grandma was a niece of “Ah Kim”, a daughter of entrepreneur Wee Boon Teck (1850–88). Ah Kim had arranged that she would be the second wife of her husband Lee Choon Guan (1868–1924) following the custom of the time. Hence, at aged 11, my grandmother arrived as a child bride from Amoy to perform the tea ceremony to her parents-in-law, Mr and Mrs Lee Chay Yan (1841–1911). Unfortunately for her, Ah Kim would die shortly from childbirth. She being too young to manage the extended household, her in-laws arranged for Choon Guan to marry socialite Tan Teck Neo, an older woman who was deemed more able to assume the management of the big household. Unfortunately the two wives did not get along and, in later years, my grandmother left “the big house” with her three children to set up her own separate residence in Kampong Bahru. My interest in history and storytelling stemmed from listening to her elaborate tales of conspiracy and intrigue involving wives, concubines and mui tsai (young girls working as domestic servants) in ancestral houses through the lively medium of Malay, Hokkien, Teochew and Cantonese.

My father, Chew Keow Seong (1912–1995), worked as an accountant in the family ship-handling firm along Robinson Road, which catered mainly to KPM and P&O liners. Visiting my father at lunchtime, I was immersed in the lively babble there – Malay to the staff who were mostly Indians including the burly Sikh watchman who placed his charpoy (a type of bed made from ropes) right across the office door each night; English or Dutch to the Caucasians; and Hokkien and a host of Chinese dialects to the ship-riggers.

To my father, reputation was more important than money, and honour and gentility were the noblest goals. This had been drummed into him by his mother, a granddaughter of Tan Hay Neo, the eldest daughter of philanthropist Tan Tock Seng (1798–1850). Nenek (Malay for “grandmother”) Hay Neo was match-made to Lee Cheng Tee (1833–1912), a Melakan trader who named his steamer “Telegraph” after the latest technological craze of the time and which sailed o the Straits Settlements, Labuan and Brunei. His family home epitomised the Peranakan love for four-poster beds, opium couches, silverware, porcelain, plaster ornaments, coloured tiles and blackwood marble furniture trimmed with gold paint. I didn’t realise then, crawling among such towering furniture, I would only see them today at museums and antique shops.

I am told that my physiognomy descends from Cheng Tee as he was tall and well-built. When I see fireworks on National Day, I remember that Cheng Tee was recorded as having sponsored a grand public dinner with fireworks galore in 1869 in honour of his new gunpowder magazine factory at Tanah Merah. The entertainment was reported by Song (1902, p. 155) as “one of the most brilliant that had taken place in Singapore”.1

Today, there are no more slopes behind the National Library to roll down from. Steamships have been replaced by air carriers. Concubinage and child marriages have been outlawed. Nurses are “allowed” to marry. The “tick-tock” hawkers have long disappeared. One thing remains constant, though: the vibrancy, multilingualism and multiculturalism that form Singapore’s heritage.

Lee Kong Chian Research Fellow (2010)

National Library

NOTES

-

Song, Ong Siang, _One Hundred Years’ History of the Chinese in Singapore_ (London: John Murray, 1923) ↩