Early Tourist Guidebooks: The Illustrated Guide to the Federated Malay States

Senior Librarian Bonny Tan examines the Illustrated Guide to the Federated Malay States, an early tourist guidebook available at the National Library.

The Audience: Early-20th-Century Globetrotters

By the first decade of the 20th century, round-the-world tours had become popular especially among wealthy Americans. These globetrotters often made a pit-stop at Singapore where they fuelled up on Western luxuries and tasted aspects of Malayan life, travelling by train as far up as Johor’s plantations before proceeding to the more exotic Far East.

To attract these tourists to stay on longer, government agencies in the region began publishing travel guides, lauding the attractions of their respective colonies and opening up sites for visits. In 1908, Java: The Wonderland was released by the Java Tourist Association,1 and at about the same time, the famed Cook tourist agency included Java in its world-tour itinerary.2 By 1909, strong colonial support led to the opening of the Angkor ruins to tourists.

The Federated Malay States, however, had yet to become a priority for Western tourists, although the Straits Settlements remained convenient stopovers. The only known guides to the Malay Peninsula were the Jennings’ Guides (1900), offering descriptions of Singapore, Penang, Melaka and the Malay States, published by the Singapore Passenger and Tourist Agency.3

Even as late as 1929, it was still felt that tourists pouring into the region had little knowledge of it nor desire to explore it, only because of a lack of information and incentive rather than the country’s lack of beauty: “As a country we don’t advertise as much as we ought to do. We are even foolish enough to think that we have nothing to advertise – that if we inveigle people into visiting this country merely as sightseers we shall be taking their money by false pretences. And yet visitor after visitor is astonished by the picturesqueness of the scenery, the attractions offered by the sight of many races mingling in a busy and more or less thriving community, and the real pleasantness of life here.”4

The Context: The Federated Malay States

The Illustrated Guide to the Federated Malay States was one such attempt to promote the attractions of the peninsula, proving to be as much a window into the politics and people of the newly cobbled Federated Malay States as it was a guide for tourist travel.

The Malay Peninsula in the late 19th century was then a patchwork of colonial rule and control, with initially only the Straits Settlements directly under British wings. Wild animals, wild men and wild habits still prevailed in interior Malaya. Author and editor of the guide, C.W. Harrison highlights the fact that “[u]p to some thirty years ago those of the Native States of the Malay Peninsula which are now the Federated Malay States, had little or no dealings with the civilizations lying east and west of them. They were unknown to history, scarce visited by other races, except the Chinese, heard of only as the wild lands forming the hinterland of Penang, Malacca and Singapore… In the Straits Settlements they were known certainly as places somewhat unsafe to visit, but for treachery and bloodthirstiness they were never comparable to the islands further south from which the sea-rovers came. Merely they were shockingly misgoverned by rulers perpetually infirm of purpose” (Harrison, 1910, pp. 4–5).

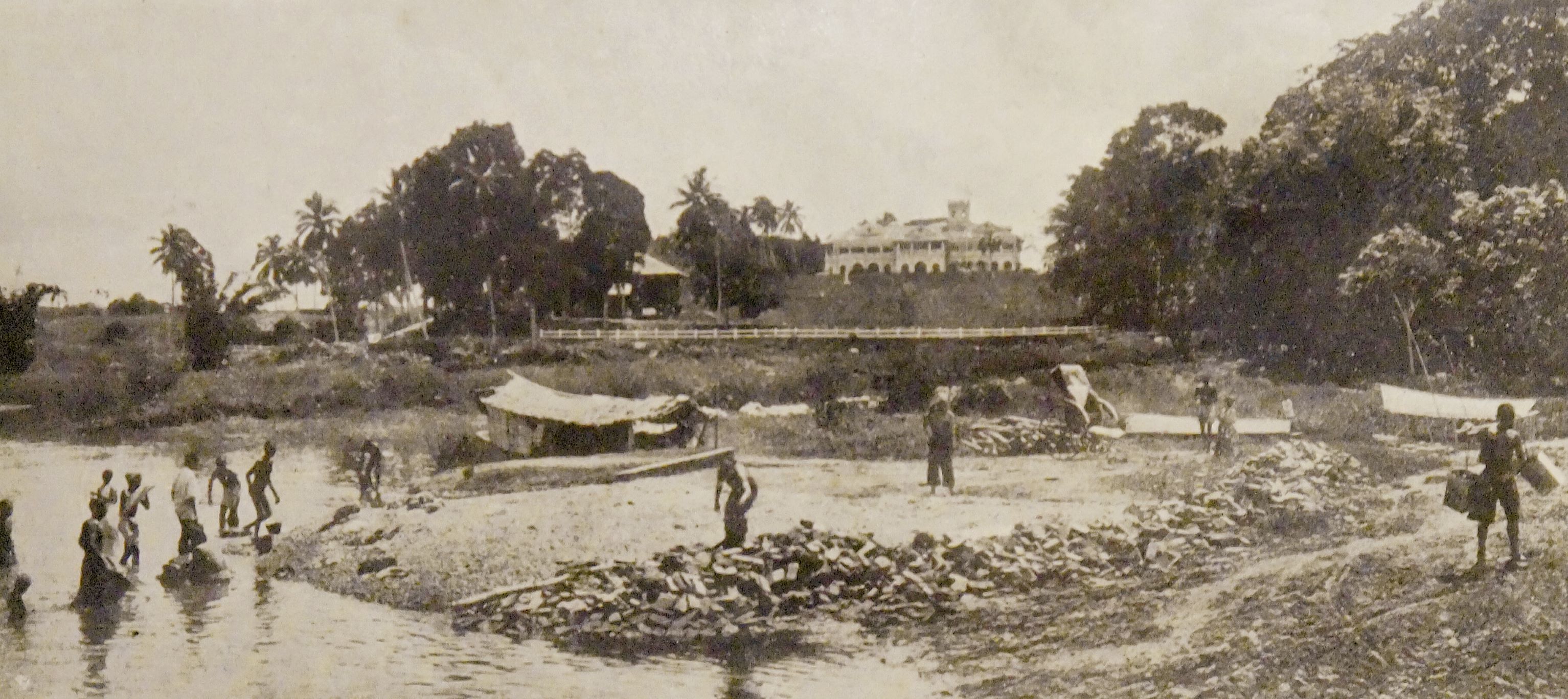

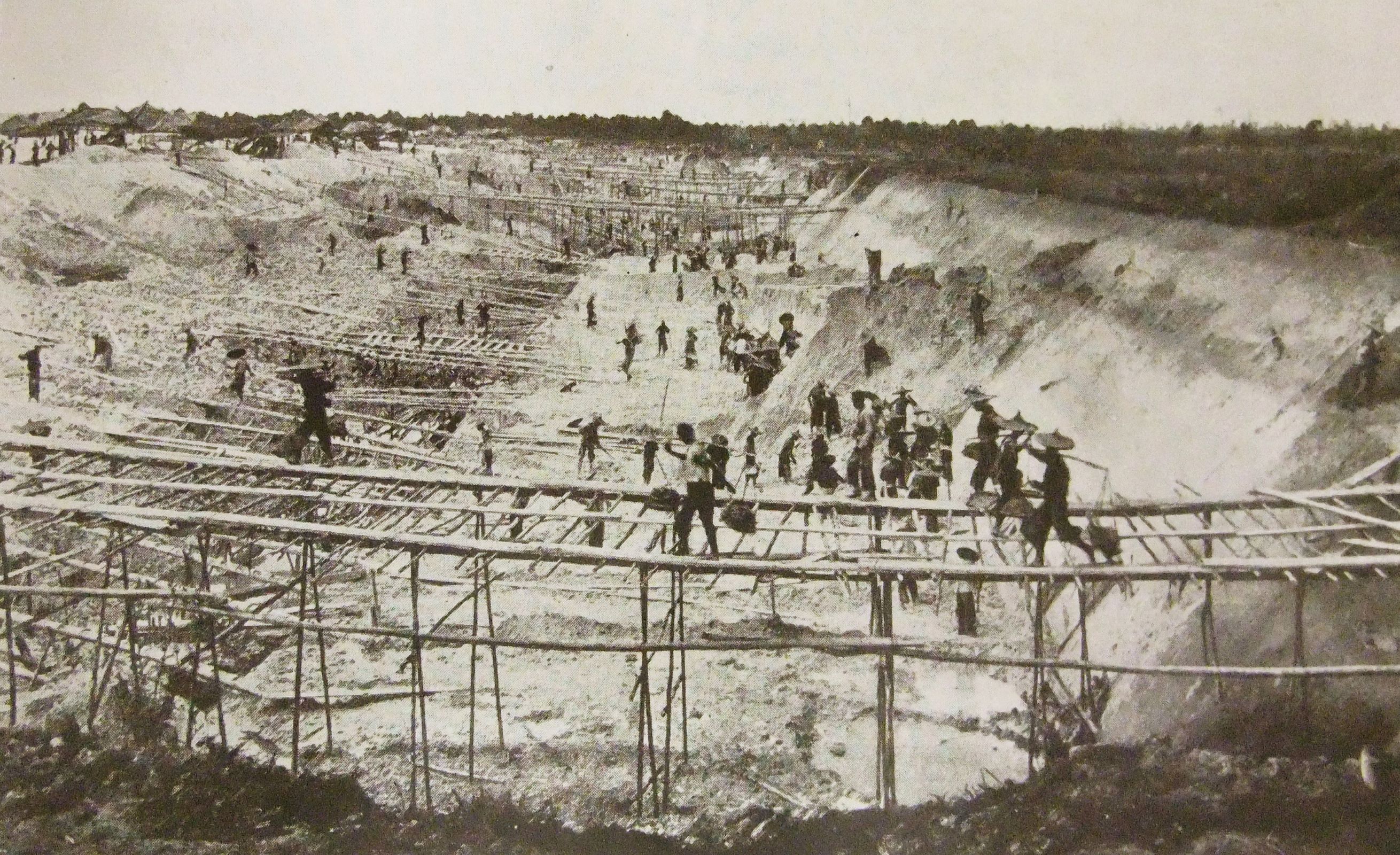

Tin mining and rubber plantations, however, were quickly transforming the landscape and society of Malaya. The guide offers details of the labour-intensive task of open-cast mining and of the Chinese coolies who worked them. “Roughly 40 percent of the world’s tin comes from the Federated Malay States. ‘Imagination boggles at the thought’ that from this little more that [sic] twenty-five thousand square miles of country, two-thirds of which are unexplored or unworked, there should be won in a year tin worth £12,244,000… and it is primarily the revenue so derived which has made the country the wealthy land it now is, and will yet make it wealthier” (Harrison, 1910, pp. 78–79). But conflicts concerning this growing wealth began to get out of hand and the ruling sultans sought the British to alleviate this problem.

When on 1 July 1896, Pahang, Perak, Selangor and Negeri Sembilan signed a treaty to form the Federated Malay States under British advisers, the British gained control over these rich industries in return for ensuring good governance and mediation over riotous conflicts which invariably arose where great wealth and anarchy were present. Meanwhile, Malayans began to taste the benefits of British influence in the development of modern infrastructure such as roads and railways as well as a strong government.

In the 1920 edition of the guide, it states that the Federated Malay States had “732 miles of railway and 2,344 miles of motor road. This makes them easy to visit, either from Penang or from Singapore… Certainly it is 8,000 miles or more overseas and takes three weeks from Marseilles, but it comes just in the middle of the grand tour between Ceylon and China or Japan and you ought not to miss it. You can rush through it in 24 hours by rail… or take the inside of a fortnight over it” (Harrison, 1910, pp. 25 –26).

The Writers and Illustrators: Products of an Empire

Harrison, along with the other writers of the guide – J.H. Robson, T.R. Hubback, H.C. Robinson and F.J.B. Dykes – had all joined the Federated Malayan Civil Service around the time of the federation.5 They were recognised as pioneers of the Federated Malay States (FMS), forging its shape while serving in more than one of the Malay States or holding a post in the main FMS government. Their writing carries the weight of personal experiences and the insights from their executive positions.6

The guide thus goes beyond giving functional descriptions of places and providing a practical itinerary. Harrison’s style particularly recalls that of travelogue writers a generation prior, with anecdotal descriptions spiced with saucy details, frank opinions and romanticised landscapes. An early review of the book notes that a “guide book is not as a rule a production which can be described as literary. If it gives accurate information it generally accomplishes all that it claims to do, and the reader looks for nothing more. The F. M. S. therefore, is particularly fortunate in having at its service a writer of the ability of Mr Harrison, who has made his guide a book which can be enjoyed for its literary qualities alone”.7

Harrison anchors the guide with two solid chapters. The first chapter captures the history of the Malay Peninsula along with a narrative of a tour by road, rail and boat from Penang to Singapore, with highlights of main towns in the Federated Malay States, namely Taiping, Kuala Kangsar, Ipoh, Tanjong Malim, Kuala Lumpur, Port Swettenham, Port Dickson, Klang and Seremban. In his descriptions, Harrison often takes the reader off the beaten track like his account of an adventure through Malaya’s jungles: “Go fifty yards off the path and you are probably lost and can only recover it by happy chances, probably will not recover it, and most likely will be obliged… to follow one of the numerous streams down the hill and emerge at the foot on to the plain with your clothes torn and your temper frayed… However much the modern traveller may long for a new sensation he is not advised to seek it in losing himself in the jungle” (p. 49). The advisory comes from Harrison himself having lost his way in the jungles in November 1908 during an organised raid on tin poachers in the Taiping hills, spending a night there before he was found the following morning.

The second chapter, entitled “Notes for the traveller”, deals with the practicalities of touring the Malay States, from what to expect at local hotels, appropriate clothing to take along, the purchase of curios and important health tips such as how to set up one’s mosquito nets. More interestingly, he gives descriptions of the agricultural and mining industries as well as of the people who work them “for the people you, as a passing traveller, will never know (for you will not leave those beaten tracks, the railway, the road, the river)” (p. 187). For example, Harrison mentions the peculiarities of the Chinese cooly (coolie) and the Malays, their food, dress, methods of work, showing an intimate knowledge of both communities. “You will see plenty of him (the Chinese cooly) in the mines and in the towns, but he is in the jungle too. You will never know him there, but think of him with his load of two bags of tin ore… Yet he is cheerful with it all and ready with a grin for anyone who, passing him, remarks sympathetically ‘Hayah, chusah-lah’ (Anglice – ‘hard work, what?’)” (Harrison, 1910, pp. 187–188).

The Malays he characterises as “senang” – a quality he sees as a strength. “This is not laziness; it is not indolence; it is not slackness; with all of which the race is unintelligently reproached. It is race-intelligence, and it means and it results in senang, and senang is the Malay for salvation, mental and physical, in this climate… The white man comes, the Chinese comes, the Indian comes, to the Malay’s country, and they live their alien strenuous lives. They make material progress and show material death and sickness rates. That is their way of being happy. It is not the Malay’s way. He rejects, and in some sense despises other people’s way, for the vast majority of him consists of ‘people in humble circumstances,’ like those described by Renan, ‘in the state so common in the East, which is neither ease nor poverty. The extreme simplicity of life in such countries, by dispensing with the need for comfort, renders the privileges of wealth almost useless and makes everyone voluntarily poor…’” (Harrison, 1910, pp. 198–199).

In chapter three, Robson describes a fascinating 11-day journey by motorcar down the peninsula, beginning at Penang, traversing through Ipoh to Kuala Lumpur and ending at Melaka via Seremban, followed by a short train ride to Singapore. This pioneer motorist who was one of the first to drive a car in Malaya,8 gives practical advice such as the appropriate type of cars to use, loading cars onto ships and trains, hiring Malay drivers and paying them.

A whole chapter of more than 20 pages on big game shooting is given by Hubback, a veteran hunter himself and who was later appointed Chief Game Warden of the FMS. Hubback advises that leopards and tigers, though fairly numerous, were less easy to hunt in the dense jungles. Instead elephants, seladang and rhinoceros made for better targets. Though Hubback advocates hunting to attract the Western traveller, he was a strong conserver of wild life in Malaya. Besides his involvement in drafting the game laws, he was the first to pursue the setting up of game reserves, with the Krau and Gunong Tahan Game Reserves in Pahang credited to his dogged determination in this matter.

Robinson, Director of the Federated Malay States’ Museums and Fisheries, solicited the help of I.H.N. Evans and C. Boden Kloss to write on the Perak and Selangor Museums respectively, giving interesting insights into the zoological as well as ethnographic collections.

F.J.B. Dykes was the Senior Warden of Mines for the Federation by 1903, having served in Malayan mines for more than a decade. He describes tin-mining methods, from hydraulic mining to basket dredging; sale and smelting of tin ore; general conditions of labour and details of legislation and export dues. He even has something to say of gold and coal mining in the Federated Malay States. By the time the guide was published, Dykes had retired to England where he served in the Malayan Information Agency, the same agency that published the guide. Updates to the article were given by F.J. Ballantyne for subsequent reprints of the guide because of Dyke’s untimely death in 1918.

Concluding the guide is a one-page glossary of Malay terms, an alphabetical listing of rest houses, details of tours with train services and various calculations of distances, monies and tariffs.

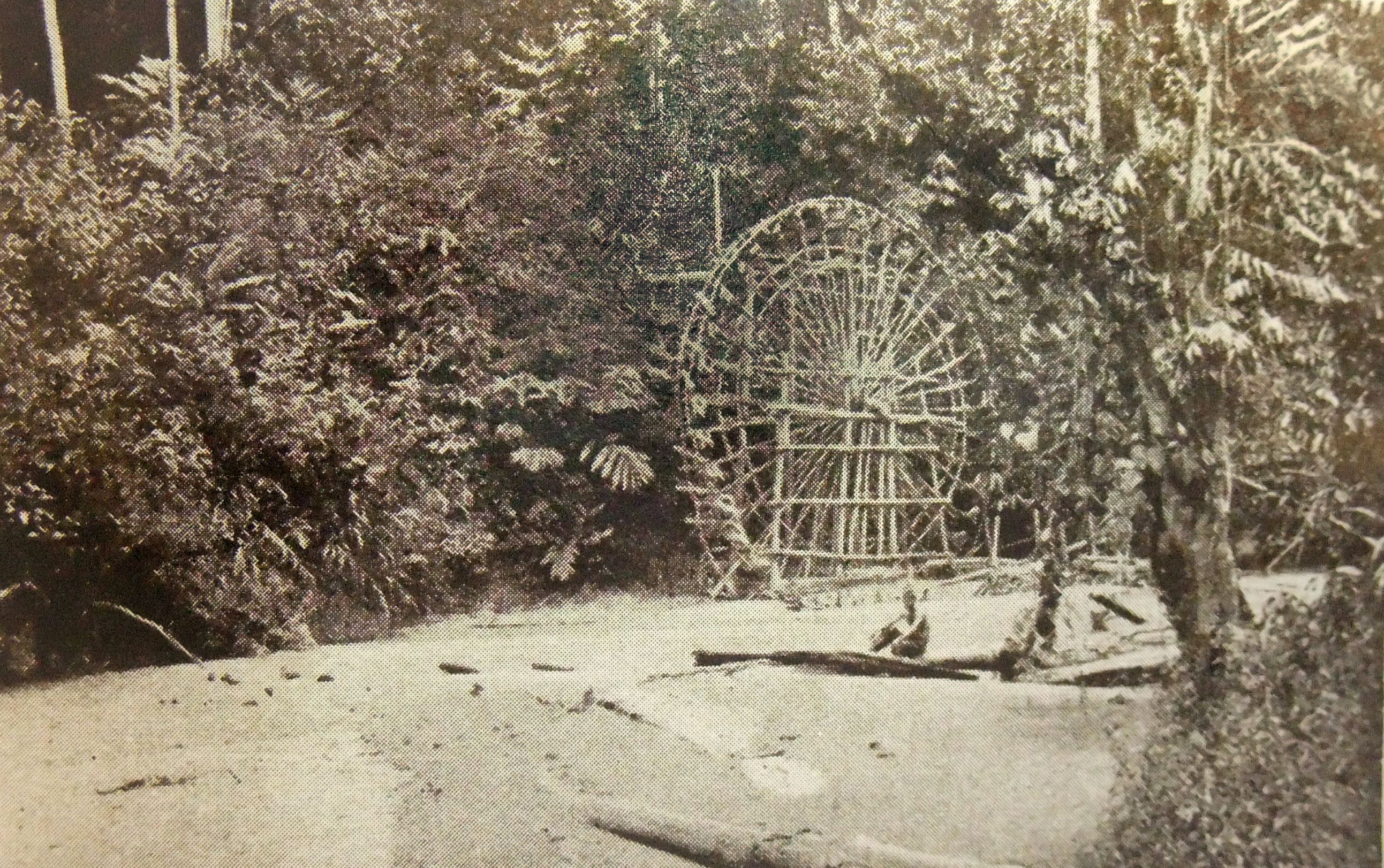

The guide is illustrated with the delicate watercolours of Mrs. H.C. Barnard and the classic photographs of the famed C.J. Kleingrothe. Barnard had accompanied her husband, who had been the divisional engineer of the FMS Railways since 1903, but was herself an active contributor to society, especially in fundraising activities. Kleingrothe was renowned for his photography of Sumatran Dutch East Indies and for his method of marketing his photography through the publication of photographic views. These photographs were originally published in the limited edition Malay Peninsula (1907), probably using the recently released Kodak Panoram camera, and are believed to date from 18849 until just a few months prior to publication. Outside of Lambert,10 Kleingrothe’s photographs are considered key visual records of colonial peninsular Malaya, especially of the tin-mining and rubber industries that were to fuel Malaya’s economic growth.

The Publisher: Malay States Information Agencies

In 1910, the Malay States Information Agency was established with the primary objective to “advertise the productions and attractions of the States of the Malay Peninsula under British protection”,11 whether to investor, government official, planter, miner, tourist or traveller. The agency, located in London, received all official publications from the Federation Malay States government. This gave it an advantage in offering useful information on statistical and trade data. If the information was not available at the agency, it had the necessary connections to contact relevant official departments in the federation to retrieve the required information. The Federated Malay States was the first among the British colonies to set up such an agency. Almost immediately upon its establishment, public interest peaked, especially in the mining and agricultural fields of the Malay Peninsula. It was such a success that soon similar agencies were established for other colonies and protectorates.

One of its first publications was the guide, printed in 1910, the same year the agency was established. Since it was released by the agency, the guide‘s contents were “officially revised and sanctioned… [and thus] regarded as a completely ‘authorised version’ of matters Malayan”.12 By the time the publication was in its fourth impression in 1923, the agency had become a well-respected institution, receiving several thousand visitors a year, offering lectures, brochures and other resources for visitors and potential investors.

In 1985, the guide was republished by Oxford University Press and it remains a vital reference for insights into the beginnings of the Federated Malay States and its growth. Copies from the first issue of 1910 to the more current reprints are available at the National Library on microfilm.

Senior Librarian

Lee Kong Chian Reference Library

National Library

REFERENCES

A Literary Guide – Mr C. W. Harrison’s Account of the F. M. S.” Straits Times, 17 July 1920, 10. (From NewspaperSG)

A. J Stockwell, “Early Tourism in Malaya,” in Tourism in South-East Asia, ed. Michael Hitchcock, Victor T. King and Michael J. G. Parnwell (London: Routledge, 1993), 258–70. (Call no. RSING 338.4791590453 TOU)

“Come to Malaya,” Malayan Saturday Post, 4 May 1929, 20. (From NewspaperSG)

Cuthbert Woodville Harrison, ed., An Illustrated Guide to the Federated Malay States (London: Malay States Information Agency, 1910). (Call no. RRARE 959.5 ILL; microfilm NL25918)

“Guide to the F. M. S.,” Straits Times, 17 December 1910, 7.(From NewspaperSG)

Han Mui Ling, “From Travelogues to Guidebooks: Imagining Colonial Singapore, 1819–1940,” Sojourn 18, no. 2 (October 2003), 257–78. (Call no. RSING 300.5 SSISA)

Java: The Wonderland (Weltevreden, Java: Official Tourist Bureau, 1910). (Call no. RSEA 915.98204 JAV)

“Jennings’ Guide,” Straits Times, 16 February 1900, 2. (From NewspaperSG)

John Falconer, “Introduction,” in Malay Peninsula: Straits Settlements & Federated Malay States (Kuala Lumpur: Jugra, 2009). (Call no. RSING 959.51 KLE)

“Lost in the Jungle,” Straits Times, 30 November 1908, 6. (From NewspaperSG)

“Malayan Outpost: The Work of the Malay States Information Agency,” British Malaya Magazine: Magazine of the Association of British Malaya (May 1926), 27–28. (Microfilm NL 7599 (1926–30)

Nan Hall, “The Tall Boy Who Came Back With an Album,” Straits Times, 17 June 1956, 1. (From NewspaperSG)

Paul Kratoska, “Introduction,” in An Illustrated Guide to the Federated Malay States, ed. Cuthbert Woodville Harrison (Singapore: Oxford University Press, 1985). (Call no. 959.5 IL)

“Pioneering Days of Motoring in Singapore,” Straits Times, 2 February 1933, 16. (From NewspapeSG)

“The Passenger Agency,” Straits Times, 10 November 1899, 3. (From NewspaperSG)

“The Story of Malayan Journalism,” Straits Times, 5 August 1934, 5. (From NewspaperSG)

“Tourist Tour in Java,” Straits Times, 13 July 1908, 7. (From NewspaperSG)

“Untitled,” Straits Times, 24 May 1920, 8. (From NewspaperSG)

“Untitled,” Straits Times, 18 August 1908, 6. (From NewspaperSG)

NOTES

-

“Untitled,” Straits Times, 18 August 1908, 6. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Tourist Tour in Java,” Straits Times, 13 July 1908, 7. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Jennings’ Guide,” Straits Times, 16 February 1900, 2. (From NewspaperSG). It was compiled by F.K. Jennings who had established the agency at 3 Finlayson Green in 1899 – “The Passenger Agency,” Straits Times, 10 November 1899, 3. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Come to Malaya,” Malayan Saturday Post, 4 May 1929, 20. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Harrison in 1897, Robson in 1889, Hubback in 1895 and Dykes in 1892. It is uncertain when H.C. Robinson arrived in Malaya. ↩

-

Harrison had been Secretary to the Residents of Selangor (1919) and Perak (1921) as well as Commissioner of Lands of the FMS (1923). Robson was a member of the Federal Council (1909) and founder and editor of the Malay Mail (1896). Hubback became Chief Game Warden of the FMS in 1933 while Robinson was Director of Museums, FMS since 1908. Dykes was appointed Senior Warden of Mines for FMS in 1903. ↩

-

A Literary Guide – Mr C. W. Harrison’s Account of the F. M. S.” Straits Times, 17 July 1920, 10. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Namely a 6 h.p. de Dion-Bouton in 1903 – “The Story of Malayan Journalism,” Straits Times, 5 August 1934, 5. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Nan Hall, “The Tall Boy Who Came Back With an Album,” Straits Times, 17 June 1956, 1. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

G.R. Lambert, well known for his black-and-white photographs of Singapore and the Malay Peninsula, was a contemporary of Kleingrothe. Kleingrothe had in fact begun his career in Southeast Asia as manager of the Deli branch of G. R. Lambert and Company. ↩

-

“Malayan Outpost: The Work of the Malay States Information Agency,” British Malaya Magazine: Magazine of the Association of British Malaya (May 1926), 27–28. (Microfilm NL 7599 (1926–30) ↩

-

“Guide to the F. M. S.,” Straits Times, 17 December 1910, 7.(From NewspaperSG) ↩