Unveiling Secrets of the Past Through the Passage of Malay Scripts

Teaching Fellow Mohamed Pitchay Gani Bin Mohamed Abdul Aziz explores the heritage of the rich Malay civilisation through its enchanting and spellbinding aksara (scripts).

“They neither built pyramids of copper,

Nor tombstones of bronze for themselves […],

But they left their heritage in their writings,

In the exhortations that they composed.”

— From the ancient Egyptian “Praise to the Scribes”1

Introduction

Early civilisations have left behind vestiges of their existence such as artefacts and monuments that glorify their achievements and accomplishments. Their scripts especially allow modern researchers to peer into the soul of their civilisations. Tham2 deduced that there are interplays between language and culture, and between culture and the environment, with regard to the Malay language and its scripts. Such synergies can be observed in the journey of the Malay manuscript from its earliest form to its modern-day script. Consequently, the interaction culminates with the oldest Malay script in the world, the oldest manuscript in Southeast Asia, and, more importantly resurrecting new insights on ancient stone inscriptions.

The Tarumanegara Stone in West Java is believed to bear the oldest known Malay script dating as far back as 400 CE. Such stone inscription artefacts are widely found in and around the Indonesian islands of Sumatra: Kota Kapur in West Bangka (686), Karang Brahi between Jambi and Sungai Musi (686), Kedukan Bukit in South Sumatra (683) and Talang Tuwo in South Sumatra (684).

Forming part of the Austronesian language family, which includes Polynesian and Melanesian languages, Malay is widely used in the Malay archipelago among some 300 million speakers in Indonesia, Malaysia, Brunei and Singapore as well as the diaspora in Thailand and other parts of Southeast Asia, Asia, East Timor and the Malay people of Australia’s Cocos-Keeling Islands in the Indian Ocean. It is understood in parts of the Sulu area of the southern Philippines and traces of it are found among people of Malay descent in Sri Lanka, South Africa and other places.

Unlocking the Secrets

Unlocking secrets of the past through critical interpretation of artefacts relating to the Malay world is the thrust of the book Aksara: Menjejaki Tulisan Melayu (Aksara: The Passage of Malay Scripts) published by the National Library Board in 2009.3 Edited by Juffri Supa’at and Nazeerah Gopaul, this book (Aksara4) traces the development of the Malay language from its earliest known source in 2 CE to the present. The evidence is captured in the form of manuscripts, books, magazines and newspapers. This coffee table book is divided into four parts: (i) the history and development of the Malay language, (ii) the coming of Islam, (iii) colonial encounters, and (iv) Singapore and modern writing. Each part is developed with a research paper on the subject and pictures of related artefacts. While this compilation may not be comprehensive, it is a valuable addition that forms an outstanding collection of bibliographical reference. The book documents the Malay heritage in the archipelago and contributes to the effort of generating more discussions and research into the world of the Malay language, literature, scripts and publications.

Evolution of the Malay Language and Scripts

Two thousand years ago, the Malay language probably started out with only 1575 words. Today, there are about 800,000 Malay phrases in various disciplines. Since 3 CE, the Malay language has undergone six stages6 of evolution: ancient form, archaic form, classic form, modern form, Indonesian form and the Internet form. These changes in forms derived from various influences that spread across Southeast Asia through colonisation and developments of new sociopolitical trends that come in tandem with globalisation.

Such waves brought with them changes to the Malay scripts as well. Scripts developed from the earliest known Rencong script, similar to the Indian script commonly used in Sumatra, the Philippines, Sulawesi and Kalimantan, to that of the pre-Islamic period, namely the Pallava, Kawi and Devanagari scripts. Later they develop into the Jawi script from the Arabic scripts and the modern Latin alphabet known as Rumi script. The Malay language evolved from ancient to the archaic form with the penetration and proliferation of Sanskrit into the local Malay language soon after the coming of the Hindu civilisation to the Malay archipelago. This was evident in the earliest stone inscriptions found in Kedukan Bukit dated 683 CE written in the Pallava script. The ancient form was also found in the Tarumanegara Stone written in ancient Malay and Javanese as well as the seven edits or yupas (long stone) discovered in Kutai, Kalimantan,7 in 400 CE.

It is the coming of Islam to Southeast Asia that elevated the Malay language to be the lingua franca. The infiltration of Arabic vocabulary into archaic Malay language turned it into the classical Malay whose usage spanned the golden age of the Malay empire of Melaka and Johor Riau. This period witnessed the flowering of Malay literature as well as the professional development in royal leadership and public administration. The Arabic language brought with it the Jawi script that became an enduring trend in the teaching and learning of Islam, especially in the Malay archipelago, till this day. The Jawi script survived the test of time even after the coming of the colonial masters and the introduction of the Romanised (Rumi) script around the 15th century.

The modern Malay language emerged in the 20th century with the establishment of the Sultan Idris Teacher Training College (SITC)8 in Tanjong Malim, Perak, in 1922. In 1936, Za’ba, an outstanding Malay scholar and lecturer of the SITC, produced a Malay grammar book entitled Pelita Bahasa that modernised the structure of the classical Malay language and became the basis for the Malay language that is in use today. The change was to the syntax, from the classical passive form to the current active form. Today the Malay language has evolved into its most complex form in the cyber and electronic world.

Unveiling the Inscriptions

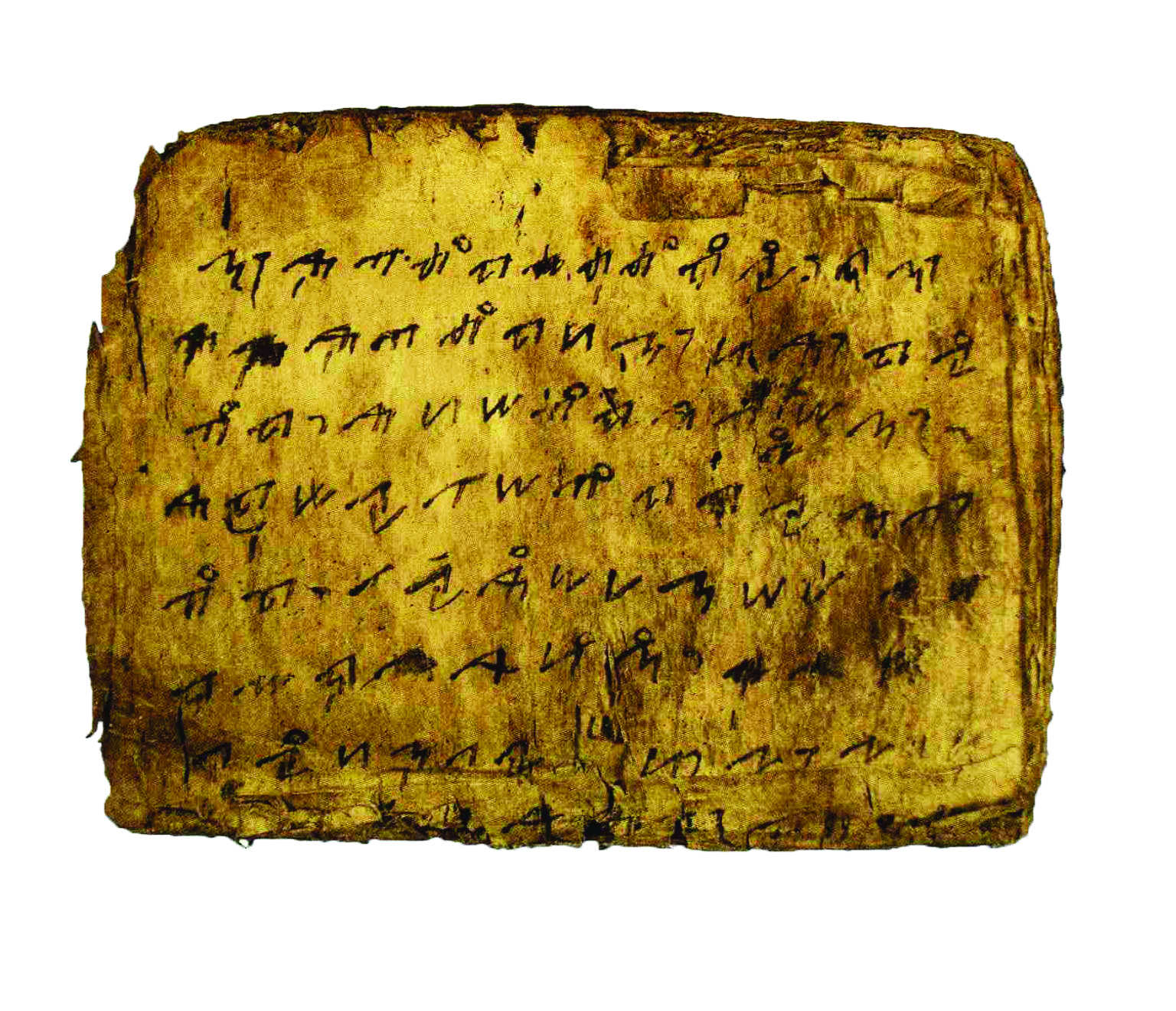

Ancient manuscripts are records written on raw and unfinished materials such as stones, palm leaves, stelae, bark and bamboo. Paper, too, became the medium of inscription for these manuscripts. The raw materials basically recorded the daily activities of the king and the people, warnings, punishments, journeys, instructions and guidance, as well as mystical elements of the king and his royal family. Perhaps beneath these recorded inkings lay much untapped potentials for a better life. For example, the Pustaha Laklak manuscript (14th century) written in the Batak script on a tree bark is a book of divination or healing written by the datu or guru (Batak magicians and healers) to record magical rituals, mantras, recipes and almanacs. The Sureq Baweng manuscript (18th century) written in the Bugis script on a Javanese palm leaf contains poda (advice) on mantras, information about how to defend oneself against bad omens, moral values and guidance for men seeking wives. Finally, the Surat Buluh manuscript (date unknown) written in Batak on bamboo is a Batak calendar. It is a divine instrument used to identify auspicious days for certain activities.

Perhaps such artefacts hold the key to some of life’s unexplained phenomena that have become of popular interest in anthropological research. In his research on Srivijaya kingdom stone inscriptions in Kota Kapur (686), Karang Brahi (686), Kedukan Bukit (683) and Talang Tuwo (684), Casparis (1975, p. 27) concluded: “they not only mark the beginning of the first great Indonesian (Malay) empire but also that of national language and of a script fully adapted to the new requirements”.9

Unveiling the Manuscripts

Important records of the early years of Singapore’s history after the British had set up a trading port in Singapore were well documented and elaborated on by Munsyi Abdullah in his autobiography Hikayat Abdullah published in 1843 in Jawi script. In fact, this book is a pragmatic document of the Malay language and the social situation of the people and the rulers then with candid yet critical accounts and observations of events. But more importantly is the true account of the concerns raised by Temenggong Abdul Rahman of Singapore prior to the founding of Singapore as documented in a letter from him to the Yang di-Pertuan Muda Riau (date unknown) written in Jawi script. The letter was written in light of the stiff competition between the British and the Dutch to secure influence in the region. The letter depicted a helpless Abdul Rahman who was administering Singapore when the British East India Company came looking for a new trading port in the Malay Archipelago. He wrote to the Riau ruler to alert him that two high-ranking British company officers, William Farquhar and Stamford Raffles, had landed in Singapore.

Nevertheless, the Temenggong finally capitulated to the British through the Treaty of 1819 written in Jawi and Rumi scripts. It was signed by Tengku Hussein and Abdul Rahman with the East India Company (EIC) recognising Abdul Rahman as sultan of Singapore and establishing EIC’s trading port in Singapore. The letter sparked a key hypothesis to engage in further research to uncover the actual scenario of the founding of Singapore. A closer scrutiny may just bring to light some unexpected conclusions.

The establishment of the British port in Singapore led to its development as an important publishing centre of the East, starting with the setting up of the Mission Press in 1819. With Munsyi Abdullah working closely with Stamford Raffles as his aide, many documents in Malay were printed, including bibles that were translated into the Malay language by Munsyi Abdullah himself. The earliest translated bibles into the Malay language published by Mission Press were: The Substance of of Our Saviour’s: Sermon of the Mount (1829) written in Rumi script, Kitab Injil al-Kudus daripada tuhan Isa al-Masehi (The Holy Bible of the Lord Jesus; 20th century) and Cermin Mata Bagi Segala Orang yang Menuntut Pengetahuan (The Eye Glass; 1859), both written in the Jawi script. It is noteworthy that the production of some bibles were in the Jawi script instead of Rumi.

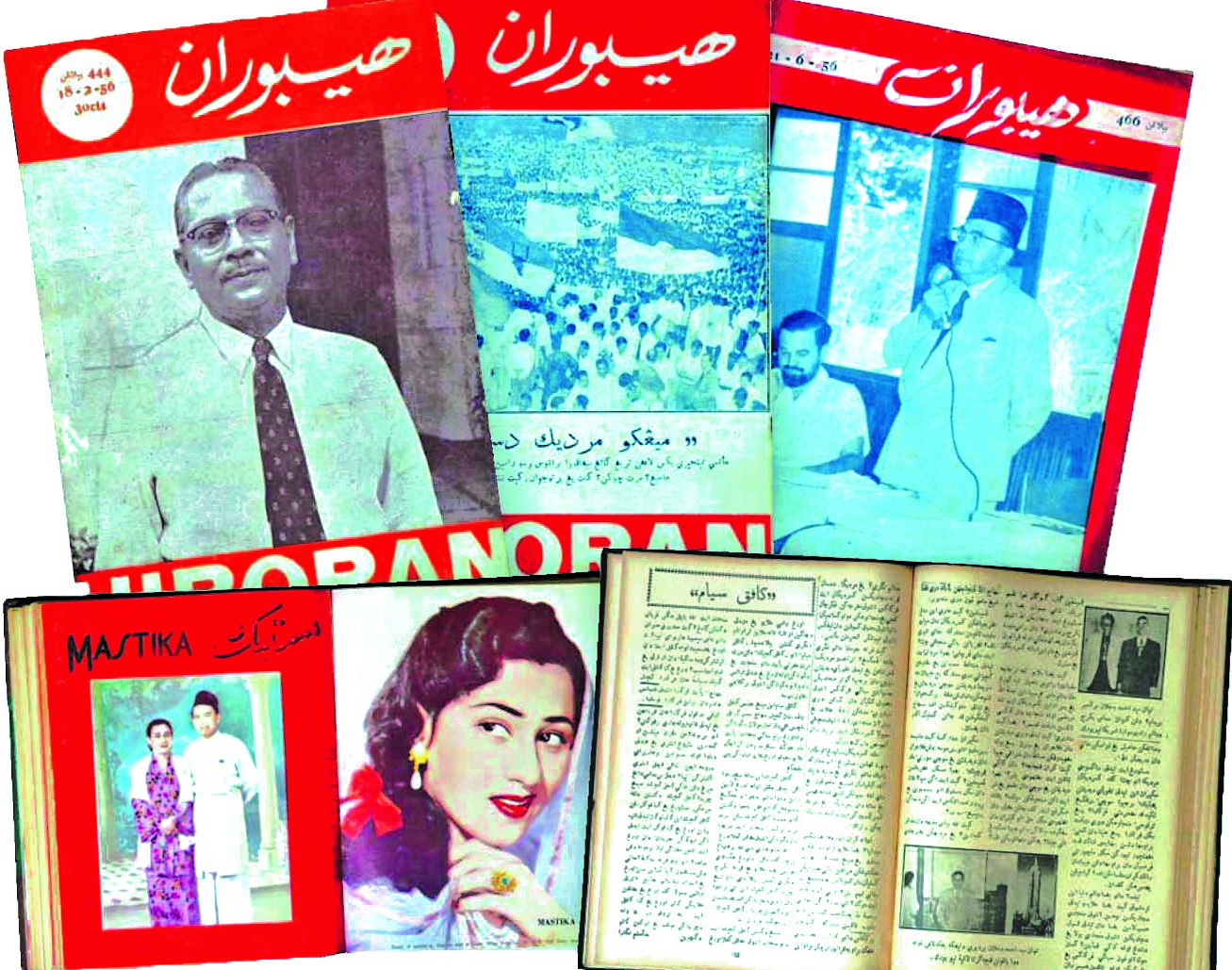

Another interesting observation is that Munsyi Abdullah, a Muslim, together with Rev. Claudius Henry Thomsen, who arrived in Singapore in 1815, translated the bible into Malay. Further research into the prominent Muslim figure Munsyi Abdullah will indeed be beneficial in understanding the link between religion and secularism. Inter-faith collaborations and intellectual pursuit were nothing new to Singapore when it became the centre of Malay films and publications. Entertainment magazines written in Jawi script such as Majalah Hiboran and Mastika flooded the market from 1956 onwards, together with novels such as Pelayan (Hostess; 1948) and Tidaklah Saya Datang ke Mari (Nor Would I Be Here; 1952) also written in Jawi script. This is on top of text books published in Jawi for educational purposes.

During the early years of Malay civilisation, documents were passed and preserved through oral tradition as Winstead10 has noted: “literature strictly came into being with the art of writing, but long before letters were shaped, there existed material of literature, words spoken in verse to wake emotion by beauty of sounds and words spoken in prose to appeal to reason by beauty of sense.” Prior to 1600, there was no collection of Malay writing in the world. According to Syed Muhammad Naquib al-Attas,11 the earliest Malay manuscript was a translated work written in 1590, Aqaid al-Nasafi. Legends, myths and folklore were constructed orally and presented through storytellers, or penglipur lara. With the coming of the colonial masters and advent of the printing machine, such genres were successfully printed into story books known as hikayat, kisah or cerita, all of which relate to stories and popular narratives.

The Malay Annals, or Sejarah Melayu, is a very important document that puts together legends, myths and history of the Malays in an acceptable form that traces the Malays’ origin and royalties as well as their meetings with other countries such as China and strategic alliances. It becomes a vital document because the iconic character Hang Tuah is adorned as the ultimate Malay warrior. Phrases like Ta’ Melayu hilang di dunia (Malays will never vanish from the face of this earth), believed to be uttered by Hang Tuah, live on till today and became a dictum for many Malay leaders and activists in their oratorical debuts.

Unveiling Pioneers of Modern Manuscripts

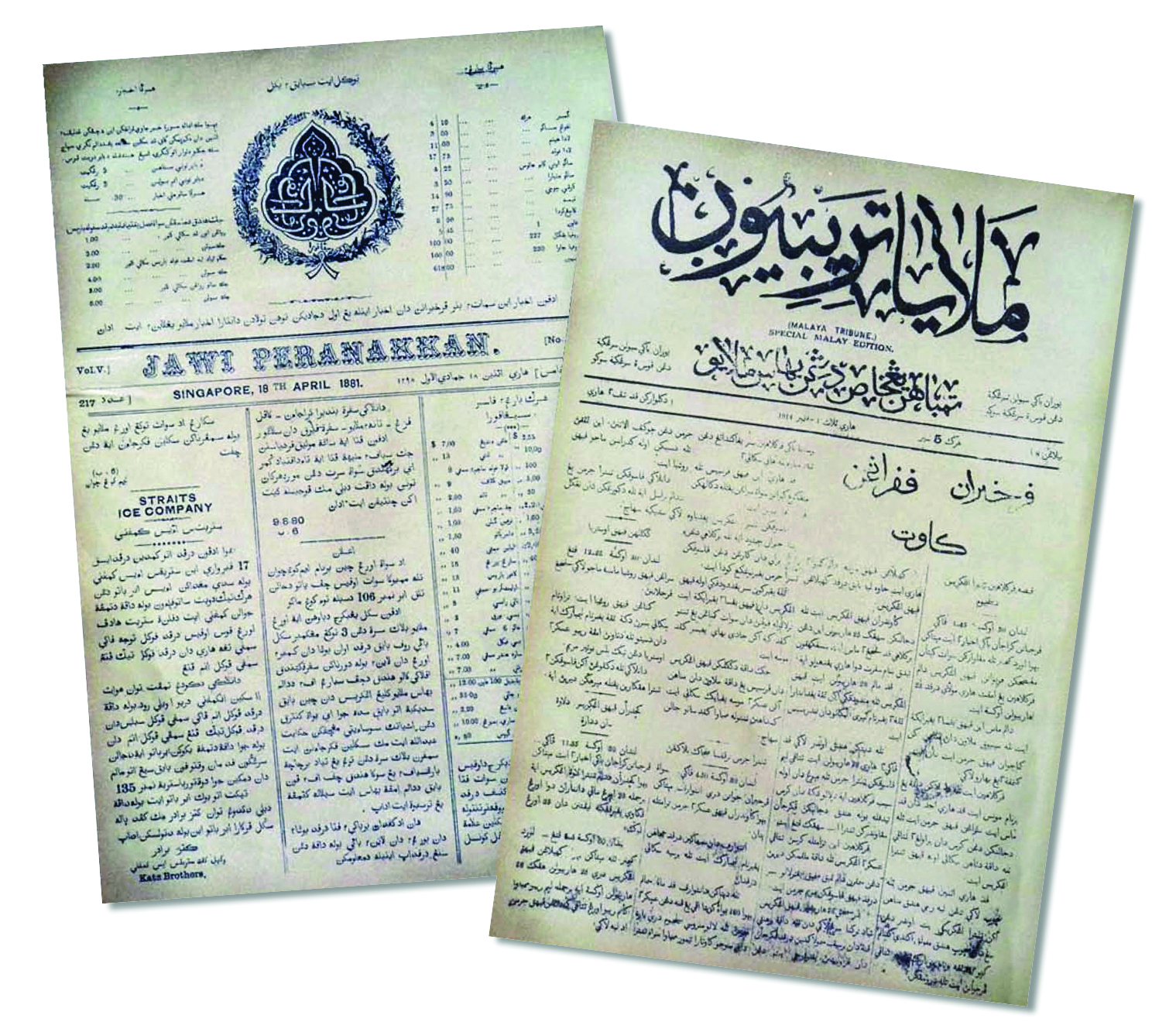

The first Malay newspaper to be published in Malaya was Jawi Peranakan (1876–95). Published in Singapore by an Indian-Muslim named Munsyi Muhammad Said Bin Dada Mohyiddin, it used the Jawi script. The first Malay newspaper to be published using Rumi script was Bintang Timor (1894) under the Chinese Christian Union with Song Ong Siang, a Chinese Peranakan, as writer. Prior to these, Munsyi Abdullah of Indian-Arab origin, wrote and published his travelogue Kisah Pelayaran Abdullah in 1838 and Hikayat Abdullah in 1840.

Interestingly, the pioneers in Malay journalism, publication and research were mainly non-Malays. In fact, the early dictionaries on Malay language were researched and produced by colonial masters such as the Dutchman Herman von de Wall who researched and published the Malay-Dutch dictionary, Maleisch- Nederlandsch Woordenboak Volumes 1 & 2, in 1877–84. Others included Dictionary of the Malayan Language, in two parts, Malayan and English and English and Malayan by William Marsden in 1812; and the Malay-French dictionary, Dictionnaire Malais-Francais Volumes 1 & 2, by Pierre Etienne Lazare Favre in 1873 and 1875. An Arab, Syed Sheikh Al-Hadi, wrote and published the first novel in Malay titled Hikayat Faridah Hanum (Story of Faridah Hanum) in 1925. However, it is considered an adaptation of a Cairo publication rather than an authentic Malay novel.12

In 1920 Nor Ibrahim13 wrote the earliest Malay short story “Kecelakaan Pemalas” (Curse of the Lazy One) which was published in the Majalah Pengasoh [Pengasuh Magazine]. The first Malay novel Kawan Benar (True Friend; 1927)14 was written by Ahmad Rashid Talu. The father and pioneer of modern Malay journalism was Abdul Rahim Kajai.15

Unveiling Gatekeepers of the Scripts

A cosmopolitan city, Singapore embraces modernity and a globalised city outlook, yet it is also an abode for ancient scripts. Apparently, there are many individuals who have preserved the scripts that may have been passed on to them by their forefathers. These include manuscripts such as the 18th-century Qur’an; a 1921 Power of Attorney document; 1951 Jawi dictionary; 1958–86 school textbooks and 1957–64 storybooks. The Aksara documents not only the history of Malay scripts but also individuals who have developed their own archives of these priceless antique literary materials. It soon becomes evident that many individuals in Singapore hold such valuable sources of knowledge and history. Among them are Ahmad Sondhaji Muhamad, Harun Aminurashid, Ahmad Murad, Ahmad Lutfi, Imam Syed Hassan Bin Muhammad Al-Attas (Ba’alwie Mosque), Koh Seow Chuan and Mahmud Ahmad. Aksara has become a modern-day index not only for artefacts but its sources as well, which include the National Library of Indonesia, Vietnam History Museum, Singapore National Library Board, National Library of Malaysia, Bodleian Library, University of Oxford, National Museum of Singapore, British Library and the Malay Heritage Centre Singapore.

Conclusion

Aksara endeavours to be the most contemporary reference while documenting classics. This is very much the case in its listing of the Dr Uli Kozok treasure from University of Hawai’i. Known as the Tanjong Tanah Manuscript, it is the oldest Malay manuscript in the world found in 2002 in Jambi, Indonesia, by Dr Uli Kozok. It was written in the later Kawi scripts16 on the bark of a mulberry tree.

According to Kozok, the translation of the manuscript, and the analysis of the language it is written in will provide new insights into the early Malay legal system, the political relationship between the coastal Malay maritime kingdoms with the upstream communities in the Bukit Barisan mountain range, as well as into the development of the Malay language since this is the oldest existing substantial body of text available in the Malay language.

The Malay civilisation may not have left behind majestic monuments or fascinating artefacts, but its heritage continues to be relayed to our generation through its enchanting and spellbinding aksara (scripts) in more than 10,000 manuscripts17 to be deciphered and interpreted to unveil secrets of the past.

Teaching Fellow

National Institute of Education

Nanyang Technological University

REFERENCES

Asmah Omar, Ensiklopedia Bahasa Melayu (Kuala Lumpur: Dewan Bahasa dan Pustaka, 2008). (Call no. Malay RSEA 499.2803 ASM)

D.G.E. Hall, A History of SouthEast Asia (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1955). (Call no. RCLOS 959 HAL)

David Crystal, The Cambridge Encyclopedia of Language (USA: Cambridge, 1993)

George Quinn, The Learner’s Dictionary of Today’s Indonesian (St. Leonards, N.S.W.: Allen & Unwin, 2001). (Call no. R 499.221321 QUI)

Hashim Musa, Epigrafi Melayu: Sejarah Sistem Dalam Tulisan Melayu (Kuala Lumpur: Dewan Bahasa dan Pustaka, 2003). (Call no. Malay RSING 499.2811 HAS)

J. G. de Casparis, Indonesian Palaeography: A History of Writing Indonesia From the Beginning to C.A.D. 1500 (Leiden: Brill, 1975). (Call no. RCLOS 499.2017 CAS)

Juffri Supa’at and Nazeerah Gopaul, eds., Aksara Menjejaki Tulisan Melayu = Aksara the Passage of Malay Scripts (Singapore: National Library Board, 2009). (Call no. Malay RSING 499.2811 AKS)

Li Chuan Siu, Ikthisar Sejarah Kesusasteraan Melayu Baru 1830–1945 [History of modern Malay literature 1830–1945] (Kuala Lumpur: Penerbit Pustaka Antara, 1966). (Call no. Malay R 899.23008104 LI)

Mohamed Pitchay Gani Bin Mohamed Abdul Aziz, “E-Kultur Dan Evolusi Bahasa Melayu Di Singapura” [E-culture and the evolution of Malay language in Singapore] (master’s thesis, National Institute of Education, Nanyang Technological University, 2004)

Mohamed Pitchay Gani Bin Mohamed Abdul Aziz, Evolusi Bahasa Melayu 2000 Tahun Dari Zaman Purba Ke Budaya Elektronik (Perak: Universiti Pendidikan Sultan Idris, 2007). (Call no. Malay RSING 499.2809 MOH)

Nicholas Ostler, Empires of the World: A Language History of the World (London. Harper Perennial, 2006). (Call no. R 409 OST)

Noriah Mohamed, Sosiolinguistik Bahasa Melayu Lama (Pulau Pinang: Universiti Sains Malaysia bagi pihak Pusat Pengajian Ilmu Kemanusiaan, 1999). (Call no. Malay R 499.2809 NOR)

Othman Puteh and Ramli Isnin, Sejarah Kesusasteraan Melayu Moden (Kuala Lumpur: Dewan Bahasa dan Pustaka, 2003). (Call no. Malay R 899.28309 OTH)

Richard Windstedt, A History of Classical Malay Literature (Kuala Lumpur: Oxford University Press, 1969). (Call no. RSEA 899.23 WIN)

Shamsuddin Jaafar, comp., Wajah: Biografi Penulis, 3rd ed. (Kuala Lumpur: Dewan Bahasa dan Pustaka, 2005). (Call no. Malay R 899.2809 WAJ)

Syed Muhammad Naquib al-Attas, The Oldest Known Manuscript: A 16th Century Malay Translation of the Aqaid of Al-Nasafi (Kuala Lumpur: Dept. of Publications, University of Malaya, 1988). (Call no. RSING 091 ATT)

Teuku Iskandar, Kesusasteraan Klasik Melayu Sepanjang Abad (Brunei: Universiti Brunei Darussalam, 1995). (Call no. Malay RCLOS 899.2309 ISK)

Tham Seong Chee, A Study of the Evolution of the Malay Language: Social Change and Cognitive Development (Singapore: Singapore University Press, 1990). (Call no. RSING 306.44089992 THA)

“UH Manoa Professor Confirms Oldest Known Malay Manuscript: Discovery Leads to International Academic Partnerships; Scholars To Gather in Jakarta in December To Attempt Translation,” University of Hawaii, 8 November 2004, https://manoa.hawaii.edu/news/article.php?aId=942

Vladimir Braginsky, The Heritage of Traditional Malay Literature (Singapore: Institute of South East Asian Studies, 2004). (Call no. RSEA 899.28 BRA)

William Gwee Thian Hock, Mas Sepuloh: Baba Conversational Gems (Singapore: Armour Publishing, 1993). (Call no. RSING 499.23107 GWE)

William R. Roff, “The Mystery of the First Malay Novel (and Who Was Rokambul),”

Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land-en Volkenkunde 130, no. 4 (1974): 450–64. From JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website.

Zalila Sharif and Jamilah Haji Ahmad, Kesusasteraan Melayu Tradisional (Kuala Lumpur: Dewan Bahasa dan Pustaka, 1993). (Call no. Malay R 899.2300901 KES)

Images reproduced from Juffri Supa’at and Nazeerah Gopaul, eds., Aksara Menjejaki Tulisan Melayu = Aksara the Passage of Malay Scripts (Singapore; National Library Board, 2009). (Call no. Malay 499.2811 AKS). All rights reserved, National Library Board. Kota Kapur Stone. Source: replica from the Museum National Indonesia. Jawi Peranakan. Source: National Library Board. Surat Buluh Manuscript. Source: National Library of Indonesia. Tanjung Tanah Manuscript. Source: Dr Uli Kozok, University of Hawai’i.

NOTES

-

Vladimir Braginsky, The Heritage of Traditional Malay Literature (Singapore: Institute of South East Asian Studies, 2004), 1. (Call no. RSEA 899.28 BRA) ↩

-

Tham Seong Chee, A Study of the Evolution of the Malay Language: Social Change and Cognitive Development (Singapore: Singapore University Press, 1990), 16. (Call no. RSING 306.44089992 THA) ↩

-

Following an exhibition by the National Library Board in 2007 that traces the evolution and transformation of the Malay writing system. ↩

-

Aksara means script in Malay. It is a Sanskrit word absorbed into Malay vocabulary. ↩

-

Noriah Mohamed, Sosiolinguistik Bahasa Melayu Lama (Pulau Pinang: Universiti Sains Malaysia bagi pihak Pusat Pengajian Ilmu Kemanusiaan, 1999), 58–60. (Call no. Malay R 499.2809 NOR) explained that the archaic Malay language had 157 Malay words or Austronesia language in its natural form. ↩

-

Mohamed Pitchay Gani’s “E-Kultur Dan Evolusi Bahasa Melayu,” produced the six stages of Malay language evolution of which the most contemporary level is the Internet language. Prior to this finding, Abdullah Hassan (1994, pp. 7–9) identified four stages of evolution. Mohamed Pitchay has added the Indonesian language and the Internet language as two more important stages of evolution to the Malay language. ↩

-

Hashim Musa, Epigrafi Melayu: Sejarah Sistem Dalam Tulisan Melayu (Kuala Lumpur: Dewan Bahasa dan Pustaka, 2003), 27. (Call no. Malay RSING 499.2811 HAS) ↩

-

SITC is the first teacher training college in Malaya proposed Deputy Director of Malay Schools, R.O. Winstead. Before SITC, there was the Malay Training College in Telok Belanga (Singapore) in 1878, relocated to Telok Ayer in 1884 and closed in 1895. There was also a Malay Training College in Malacca (1900) and Perak (1913). These two colleges were amalgamated to form SITC. It was designed to provide teacher training and education to only the highest achieving Malay students in pre- independent Malaya. In 1997, it was upgraded to become the Sultan Idris Education University. ↩

-

Casparis (Musa, Epigrafi Melayu, 29) classified the scripts found in the Srivijaya manuscripts as the later type of Pallava scripts and much more developed compared with the earlier scripts. As such, it is also classified as the Bahasa Melayu Tua or the ancient Malay language. ↩

-

Richard Windstedt, A History of Classical Malay Literature (Kuala Lumpur: Oxford University Press, 1969), 1. (Call no. RSEA 899.23 WIN) ↩

-

Syed Muhammad Naquib al-Attas, The Oldest Known Manuscript: A 16th Century Malay Translation of the Aqaid of Al-Nasafi (Kuala Lumpur: Dept. of Publications, University of Malaya, 1988), 6–8. (Call no. RSING 091 ATT) ↩

-

William R. Roff, “The Mystery of the First Malay Novel (and Who Was Rokambul),” Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land-en Volkenkunde 130, no. 4 (1974): 451. (From JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website) ↩

-

Othman Puteh and Ramli Isnin, Sejarah Kesusasteraan Melayu Moden (Kuala Lumpur: Dewan Bahasa dan Pustaka, 2003), 3. (Call no. Malay R 899.28309 OTH) ↩

-

Shamsuddin Jaafar, comp., Wajah: Biografi Penulis, 3rd ed. (Kuala Lumpur: Dewan Bahasa dan Pustaka, 2005), 163. (Call no. Malay R 899.2809 WAJ) ↩

-

Jaafar, Wajah: Biografi Penulis, 80. ↩

-

It is believed to be the oldest existing Malay manuscript because it is written in the later Kawi scripts. The manuscript is a legal code of 34 pages completely written in Malay except for the first and last few sentences, which are written in Sanskrit. The material the text is written on is bark paper produced from the bark of the mulberry tree, and the script is an Indian-derived script, which developed locally in Sumatra. Kozok found the manuscript in 2002. It had been kept in a private collection in a remote part of Sumatra where villagers regard it to be a sacred heirloom with calamity befalling the village should it be removed. ↩

-

Braginsky, Heritage of Traditional Malay Literature, 1. ↩