Education for Living: Epitome of Civics Education?

Lee Kong Chian Research Fellow Chia Yeow Tong examines the reasons for the emergence of Education for Living, regarded as the de facto civics education programme in 1970s Singapore, and why it was subsequently abandoned.

Forging a sense of national identity has always been high on the agenda of the Singapore government. Ever since the country’s independence, various civics and citizenship education programmes have been set in motion, only to be subsequently discontinued and replaced with other initiatives. Education for Living (EFL) was regarded as the de facto civics education programme in 1970s Singapore. We look at the reasons that led to the emergence of the programme and why it was abandoned.

Advent of EFL

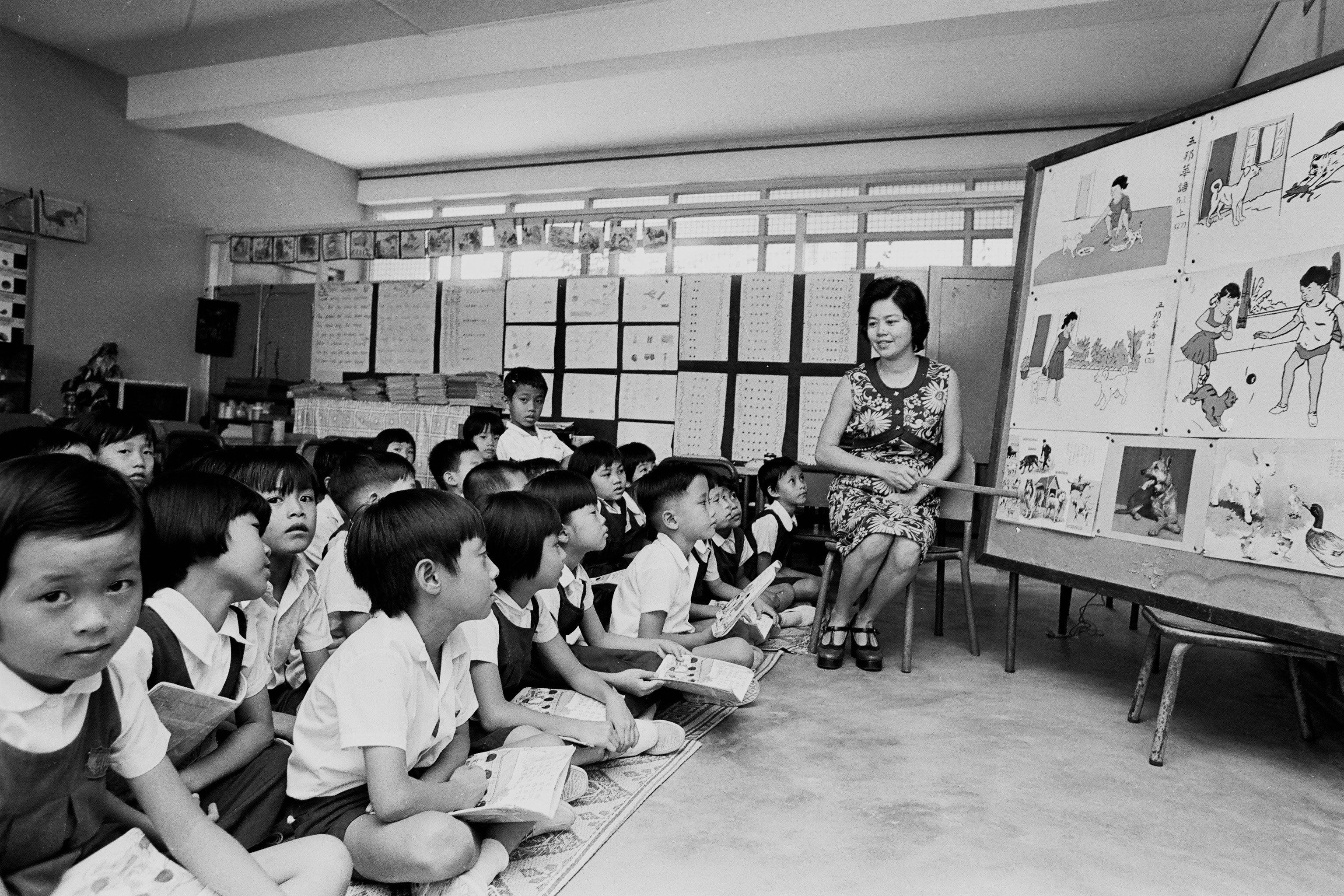

Developed for the purpose of imparting social and moral education, EFL integrated civics with history and geography. This was considered necessary to “help pupils to understand and live under the changing conditions” (Chew, 1988, p. 72; Ong, 1979, p. 2).

The objectives of EFL were as follows:

• To help pupils become aware of the purpose and

importance of nation building and their duties as

loyal, patriotic, responsible and law-abiding citizens.

• To enable pupils to obtain a better understanding of

how [Singapore] developed and of [its] geographical

environment.

• To help pupils to understand and appreciate

the desirable elements of Eastern and Western

traditions.

• To guide pupils to perceive the relationship between

man and society and in turn, between society and

the world, so that they would be able to live in a

multi-racial and multi-cultural society in peace and

harmony. (Ong, 1979, p. 3)

It is interesting to note that while the EFL syllabus aimed to introduce students to the best of Eastern and Western values, there was to be a shift in orientation towards the end of the 1970s wherein the West was demonised and the East valorised.

Like Civics, EFL was taught in the mother tongue. The government believed that “Asian moral and social values, and the attitudes such as closeness in family ties, filial duties and loyalty [could] be conveyed and understood better in Asian languages”, and that pupils would become more aware of their cultural roots and develop a stronger sense of nationhood “if they knew their own language” (Gopinathan, 1991, p. 279). Christine Han (1996) challenged this assumption:

The insistence for moral and civic values to be taught in

the mother tongue raises questions, first, as to whether

there is a necessary link between language and values

and, second, as to whether there is a conflict between

attempts to build a nation and the fostering of ethnic

culture and identity through an emphasis on ethnic values

and languages.1

Introduced to all primary schools in 1974, the instructional materials for EFL came in the form of 12 textbooks, which worked out to two textbooks per grade level, with accompanying teacher’s guides. The themes covered in the syllabus included the following: our family, our life, our school, our culture, our environment, how our people earn a living, our public services, our (role) models, our society, our community, our country, our world, and our moral attitude. The chapters in the textbooks were written in the form of short passages, like previous civics textbooks, with questions for discussion at the end of each passage. Although the EFL syllabus was organised more systematically than the previous primary school civics syllabus, it covered most of the contents of the previous syllabus, including topics associated with history and geography.

Dr Lee Chiaw Meng, the Education Minister, went to great lengths to explain why “the teaching of civics and moral education” was not “an examination subject”. This was because “[Singapore’s] examination system is… too examination-oriented. By adding another subject, we could make matters worse. They might learn it by heart without really wanting to know why certain things ought to be done” (Parliamentary Debates, 26 March 1975, vol. 34, col. 1000). Moreover, the subject matter of the EFL syllabus was rather extensive since it incorporated the study of civics, history and geography.

It was clear that the Ministry of Education (MOE) intended EFL to be the epitome of the civics curriculum. This was clearly indicated in the MOE’s Addendum to the Presidential Address at the opening of the Fourth Parliament:

Moral and civics education is mainly taught through the

subject Education for Living (which is a combination of

Civics, History and Geography) in the pupils’ mother

tongue. The aim of the subject is to inculcate social

discipline and national identity and to imbue in pupils

moral and civic values. (ibid., 8 February 1977,

vol. 36, col. 40).

The addendum conveniently ignored the presence of the existing civics syllabus for secondary schools, giving the impression that the subject was only taught at the primary level.

Therefore, it came as no surprise when a Member of Parliament suggested that the MOE extend “Education for Living to the secondary schools and that the historical development of Singapore, in particular, the periods of crises and hardships be included in the curriculum… [and] should be taught as a compulsory subject in the secondary schools” (ibid., col. 90). The Senior Minister of State for Education responded to this by stating that subjects like Civics, History and Geography assumed the role of EFL by imparting values to students at the secondary school level (ibid., 23 February 1977, col. 390–91).

By 1976, members of Parliament (MPs) were beginning to raise concerns with EFL during the annual budget and Committee of Supply debates. Chang Hai Ding, who advocated the teaching of history in schools, while acknowledging that “[patriotism] is… included in our Education for Living” (ibid., 20 March 1978, vol. 37, col. 1226), argued that “the misbegotten subject Education For Living” was unable to inculcate patriotism amongst students (ibid., 14 February 1977, vol, 36, col. 68). Another MP criticised EFL for developing into “neither a civics lesson, nor an Education for Living lesson but in many schools, it has become a second language lesson”, and called it “a failure” (ibid., 23 March 1976, col. 830). There was a call for “Education for Living [to] be taught by Education for Living teachers, not by second language teachers” (ibid., 23 March 1976, vol. 35, col. 821). One MP sarcastically even referred to it as “Education for the Living” (ibid., 15 March 1976, col. 292). The Senior Minister of State for Education did not address the criticisms of EFL in his reply. He merely reiterated the aims of EFL – “to inculcate moral and ethical values in our young pupils” (ibid., 23 March 1976, col. 855) – and gave an overview of the EFL topics.

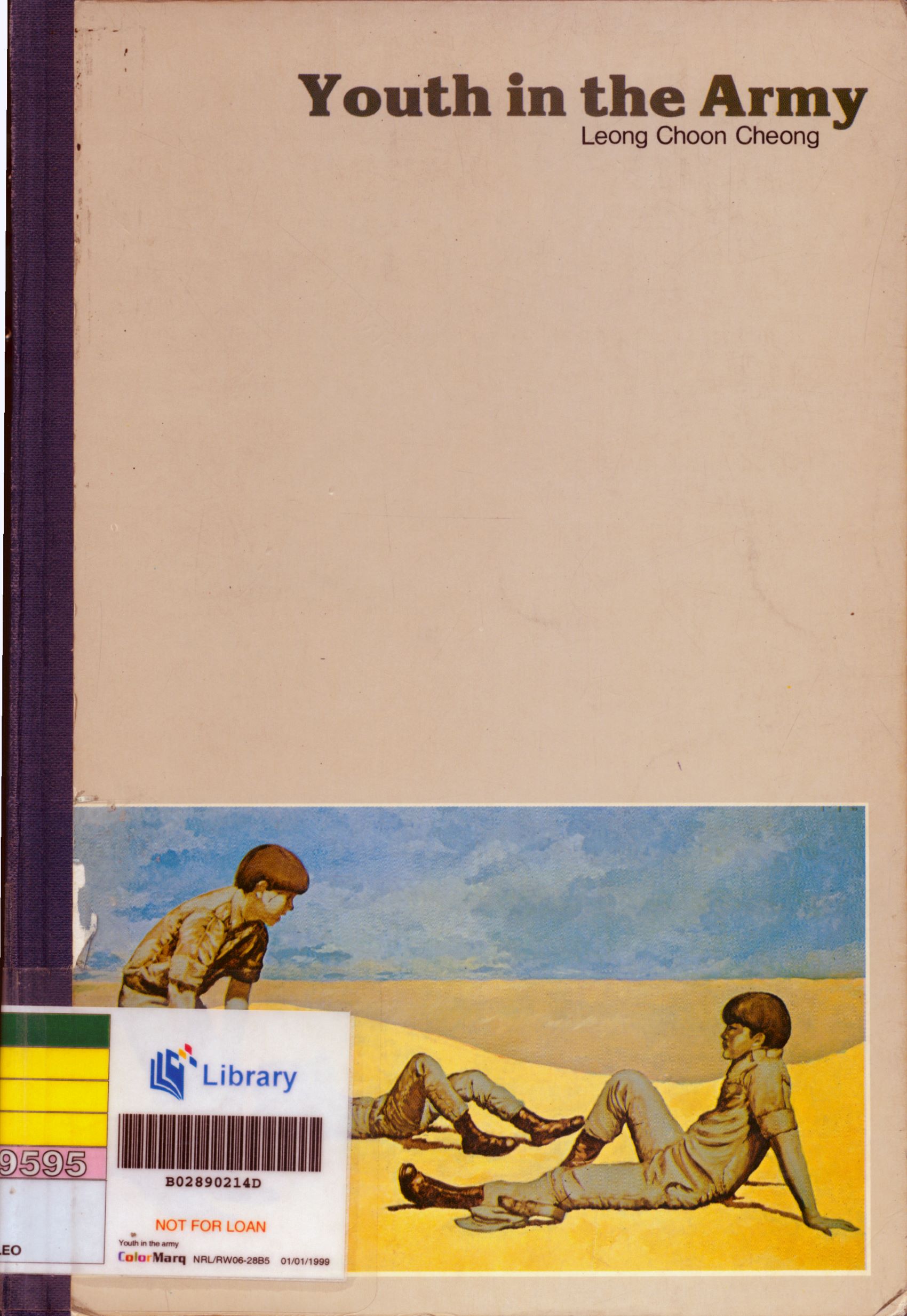

The criticisms of EFL by MPs were echoed by Leong in his study on youths in the army, where he argued that the teaching of EFL in Mandarin essentially became a second-language lesson rather than a civic one. Students in the English stream of English-medium schools would be more focused on deciphering the language rather than contemplating the message of the lesson because of their predilection towards English learning. Another reason for the ineffectiveness of the teaching of EFL in Chinese is that only teachers proficient in Chinese could teach it, which could result in the concepts of being taught within a language lesson framework instead of through a civics lesson paradigm (Leong, 1978, p. 9).2 In short, Leong was highly critical of EFL, contending that “the explanation of aims is couched in generalities”, of which “[s]ome of the generalities are nebulous in character” (ibid., p, 8).

Demise of EFL and Civics

Leong’s criticisms of EFL found resonance with the report published by the Education Study team, more popularly known as the Goh Report, as the team was chaired by Goh Keng Swee, then Deputy Prime Minister and Minister for Defence:

Much of the material in the EFL textbooks, particularly

those for lower primary classes, are useful in

inculcating useful attitudes such as respect for honesty,

hard work, care for parents and so on. A good deal of it,

however, is irrelevant and useless. Subjects such as the use

of community centres, functions of government outpatient

clinics are of little value in inculcating moral beliefs

in children. (Goh, 1979, p. I-5).

The Goh Report’s observations on the secondary schools’ civics syllabus were even more scathing:

Much of the material taught relates to information,

some useful, others of little permanent value. For

instance, it seems pointless to teach secondary school

children the details of the Republic’s constitution, much

of which is not even known to Members of Parliament. It

is better that children are taught simple ideas about what

a democratic state is, how it differs from other systems

of Government and what the rights and responsibilities of

citizens of a democratic state are. (ibid.)

In 1978, the Prime Minister commissioned the Education Study Team to conduct a major review of the problems faced by Singapore’s education system. A reading of Singapore’s Parliamentary Hansard in the 1970s revealed that many aspects of Singapore’s education system were heavily criticised by the MPs during the annual Committee of Supply debates — the criticisms of EFL were but one of many items over which the MPs took issue with the MOE. What prompted the review was the high drop-out rate following the implementation of mandatory bilingual education, which the Goh Report termed as “educational wastage”. The major recommendation of the study team was the streaming of students at the Primary Three level according to English language ability. This was to have major implications on Singapore’s educational landscape in the years to come. The resultant education structure was referred to as the “New Education System”.3

While the Goh Report commented on EFL and the civics syllabus, the teaching of civics was not the primary focus of the Education Study Team. The Prime Minister’s open letter to the Education Study Team, which was published in the Goh Report, reflected his thinking on the role of education in general, and on civics and citizenship education in particular. In his letter, the Prime Minister pointed out that he Goh Report did not touch upon moral and civics education. He regarded a good citizen to be “guided by moral principles” and imbued with “basic common norms of social behaviour, social values, and moral precepts which make up the rounded Singaporeans of tomorrow” (Goh, 1979, pp. iv–v). Thus, “[t]he best features of our different ethnic, cultural, linguistic, and religious groups must be retained…. No child should leave school after 9 years without having the ‘soft-ware’ of his culture programmed into his sub-conscious” (ibid., p. v). This is reminiscent of a speech he delivered in November 1966 where he decried the lack of social and civic responsibility in schoolchildren. The Prime Minister’s main concern was evidently based on the importance of instilling a sound moral upbringing in students, and not so much on teaching the theoretical aspects of civics and democratic values. Moreover, he apparently found the existing civics education programmes wanting in the teaching of moral values.

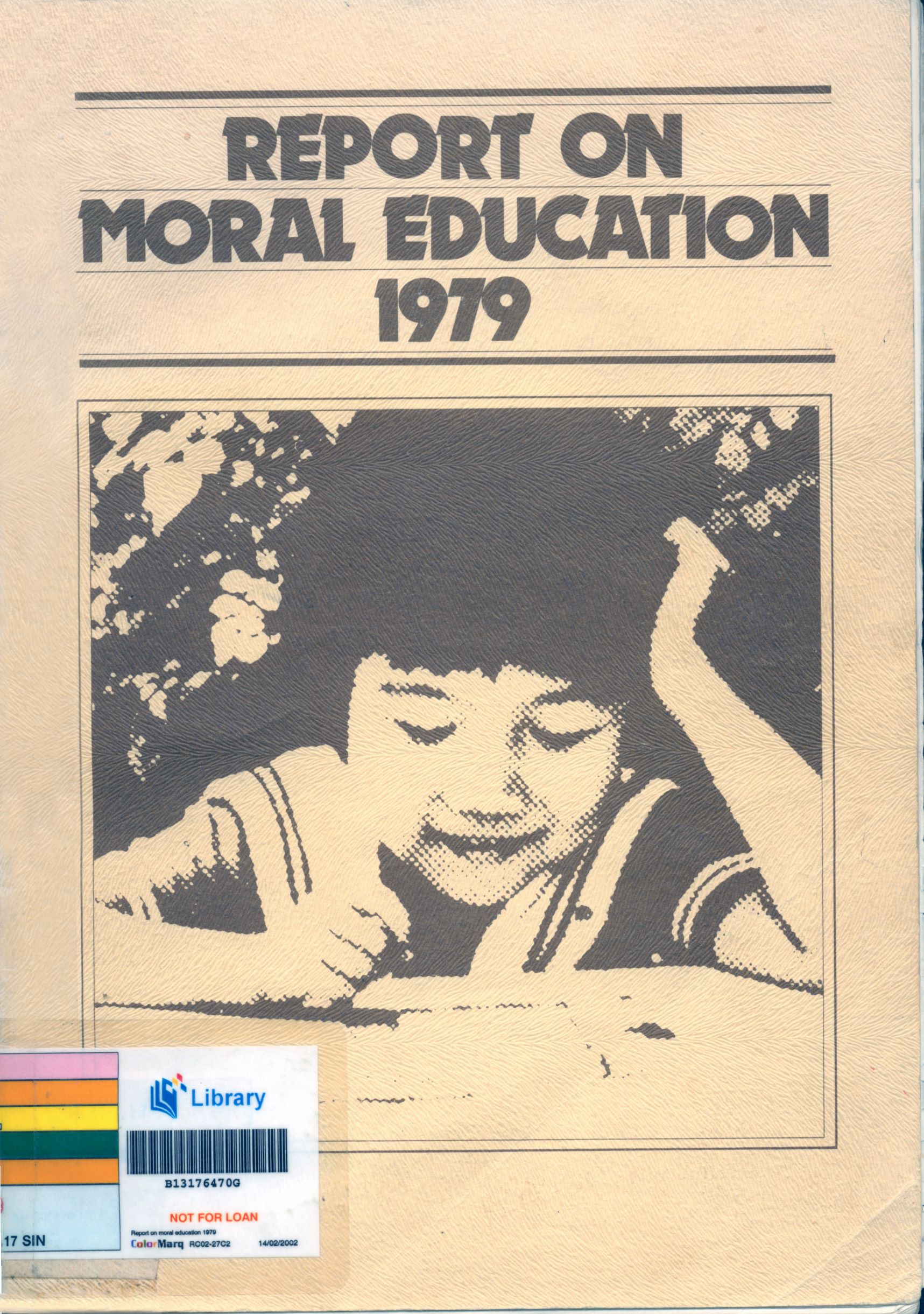

In response to the Prime Minister’s concerns on moral education, in October 1978, the Deputy Prime Minister appointed Ong Teng Cheong, Minister for Communications and Acting Minister for Culture, to head a team of parliamentarians to “examine the existing moral education programme in schools” (Ong, 1979, p. i). The objectives of this Committee were as follows:

• To identify the weakness and strengths of the

existing moral education programmes in schools.

• To make recommendations on the content of moral

education programmes and teaching methods to

be used in both primary and secondary schools.

• To make recommendations on the selection of

suitable teachers to carry out moral instructions in

schools. (ibid., p. 1).

Unlike the Education Study team, which had no terms of reference, the Moral Education Committee had specific guidelines. First, it had to determine the best ways in which to instill within students desirable moral values (honesty, industry, respect for family, cleanliness and thrift). Next, it had to reassess the existing Education for Living Program in primary schools and the Civics syllabus in secondary schools. The Committee also had to make recommendations on how to select teachers who could teach the moral education program in schools (ibid.).

In July 1979, the Moral Education Committee released its report, popularly referred to as the Ong Teng Cheong Report, or Ong Report. The report observed that “Civics and EFL are two different and distinct programmes handled by two different subject committees”, resulting in a lack of continuity and reinforcement of “the inculcation of desirable moral and social attitudes in Primary and Secondary Schools” (Ong, 1979, p. 4). This was because “each committee works on its own, each with a different approach and emphasis” (ibid.).

The Moral Education Committee found the EFL syllabus to be “on the whole quite appropriate and acceptable”, apart from these shortcomings:

• Since EFL combines the teaching of Civics, History and

Geography, some of the so-called social studies topics and

concepts such as the public services and the history

and geography of Singapore are irrelevant to moral

instruction.

• There is not sufficient emphasis on the more important

moral concepts and values.

• Some of the moral concepts dealt with at the lower

primary level such as concepts of “love for the

school”, “service” and “duty”, are highly abstract and may

pose difficulties for the six-year-olds conceptually.

They should be deferred to a later stage.

• It was also too early to introduce situations involving

moral conflict situations at the primary school level in the

manner adopted in the EFL textbooks. It will

probably be more effective to tell stories of

particular instances of moral conflicts with particular

solution or solutions, leaving generalisations to a later

stage in the child’s intellectual development (ibid.,

pp. 4–5).

With regard to the EFL textbooks, the committee found that at the lower primary level, EFL textbooks are adequate, although some lessons ought to be replaced with more suitable ones. In particular, more lessons in the form of traditional stories or well-known folktales should be included in the text to convey the desired moral values and concepts. At the upper primary level, the textbooks are dull and unimaginative, and it is doubtful that they can arouse the interest of the pupils. The link between the moral concepts being conveyed and their relevance in terms of the pupils’ experience is tenuous (ibid., p. 5).

Like the Goh Report, the Ong Report was more critical of the secondary schools’ civics syllabus:

• It has insufficient content on the teaching of moral

values. It includes too many varied subjects which

have little or nothing to do with morality…

unnecessarily detailed descriptions of trivial topics

tend to take up an inordinate amount of time at

the expense of other more important areas… key

issues such as good citizenry, the need for national

service and the inculcation of desirable moral

values are not given sufficient coverage and emphasis.

• The subjects and topics are repeated at each

level from secondary one to four without any substantial

changes or graduation of depth of treatment.

This makes the lessons uninteresting and boring … .

• Some subjects are far too advanced and are

therefore beyond the comprehension of the

students, e.g. topics like the constitution, legislation

and international relations (which are introduced

as early as Secondary one and two). (ibid., p. 4)

As for the Civics textbooks, they were found to be “generally dull and somewhat factual and dogmatic… There is also insufficient illustration of the desired moral values… through the use of stories… Where this is done, it is… boring and unimaginative” (ibid., p. 5).

In short, the Ong Report criticised “[t]he present moral education programme [to be] inadequate and ineffective, particularly in the case of the Civics programme in the secondary schools” (ibid., p. 8). The only saving grace lay with the objectives for EFL and Civics, which were deemed “appropriate and relevant” (ibid., p. 4). In the light of the strong criticisms from the Moral Education Committee, its recommendation came as no surprise:

It is recommended that the present EFL and Civics

programme be scrapped and replaced by one single

programme covering both the primary and secondary

levels under the charge of a single subject standing

committee. The subject should be called “Moral Education”

and it should confine itself to moral education and

discipline training of the child. (ibid., p. 8)

Thereafter, the affective aspect of civics and citizenship would be imparted by moral education, while the more cognitive domains would be covered in social studies and history.

Conclusion

Introduced with much promise, the EFL programme was initiated with the objective of combining history, geography and civics, in addition to imparting moral values. However, it was eventually scrapped since the government was more concerned with instilling strong moral ideals rather than offering theoretical lessons in civics and democratic values. Another reason for the programme’s failure was the fact that EFL lessons were used to teach Chinese – since the booklets and the accompanying teachers’ manuals were published in Chinese. EFL was the epitome of civics education in Singapore in the 1970s, but only for a very short time.

The author wishes to acknowledge the contributions of Dr Ting-Hong Wong, Institute of Sociology, Academia Sinica, Taiwan, in reviewing the paper.

Lee Kong Chian Research Fellow (2010)

National Library

REFERENCES

Christine Mui Neo Han, “Education for Citizenship in a Plural Society: With Special Application to Singapore,” (PhD diss., Oxford University, 1996)

Goh Keng Swee and The Education Study Team, Report on the Ministry of Education 1978 (Singapore: Ministry of Education, 1979). (Call no. RSING 370.95957 SIN)

Joy Ooni Ai Chew, Moral Education in a Singapore Secondary School (Monash: Monash University, 1988)

Leong Choon Cheong, Youth in the Army (Singapore: Federal Publications, 1978). (Call no. RSING 155.532095957 LEO)

Ong Teng Cheong and [the] Moral Education Committee, Report on Moral Education 1979 (Singapore: Ministry of Education, 1979). (Call no. RSING 375.17 SIN)

Parliament of Singapore, Parliamentary Debates: Official Report (Singapore: Government Printer, 1965–). (Call no. RSING 328.5957 SIN) (various volumes)

S. Gopinathan, “Education,” in A History of Singapore, ed. Ernest C.T. Chew and Edwin Lee (Singapore: Oxford University Press, 1991). (Call no. RSING 959.57 HIS)

Soon Teck Wong, Singapore’s New Education System: Education Reform and National Development (Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, 1988). (Call no. RSING 370.95957 SOO)

Wendy D. Bokhorst-Heng, Language and Imagining the Nation in Singapore (Toronto: University of Toronto, 1998). (Call no. RSING 306.44095957 BOK)

NOTES

-

This assumption continues to this day. See Wendy D. Bokhorst-Heng, Language and Imagining the Nation in Singapore (Toronto: University of Toronto, 1998). (Call no. RSING 306.44095957 BOK) ↩

-

Leong was examining the problems faced by the conscript soldiers, and found that the failure of bilingual education was one of the contributing factors. Leong’s criticism of EFL meant also that bilingual education was not working as well as it should. ↩

-

For an explanation of streaming and the New Education System, see Soon Teck Wong, Singapore’s New Education System: Education Reform and National Development (Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, 1988). (Call no. RSING 370.95957 SOO) ↩