Asian Confluence: Challenging Perceptions of European Hegemony

Visiting Senior Research Fellow at the Institute of Southeast Asian Studies Dr Arun Bala argues that a confluence of different Eastern cultures, along with the Western tradition, led to modern science and the Singapore that we know today.

The history of Singapore has traditionally been narrated from the perspective of its discovery by Stamford Raffles in 1819 and its subsequent development from a sleepy village to a modern metropolis. The passing of the colonialist regime and the developments that followed post-independence continued the basic narrative, showing how postcolonial Singapore built upon British colonial heritage. This narrative assumes that the major turning point in Singapore’s history occurred in the early 19th century when the forces that shaped Singapore’s future began to come into play and distinguish the new country from its antiquarian past.1

This narrative parallels the version of the history of modern science that most Singapore students imbibe at school. Students learn that modern science emerged in Europe in the 17th century and that the subsequent phenomenal advances Europeans made in this field exemplify why it was the Europeans – rather than any other people – who founded Singapore two centuries later, transforming it into a successful trading city. What is significant about these origin stories is that the major cultures that came to constitute the population of Singapore – Chinese, Malay-Islamic and Indian – are not recognised as having played significant roles as formative influences on the birth of either Singapore or modern science. Instead these cultures are seen as adapting themselves to the society and science that prevail in Singapore today, which are largely the creation of the West.

However, recent studies question this Eurocentric understanding of Singapore society and the science that drives it. These studies argue that the major Asian cultures – Chinese, Malay-Islamic and Indian – that contributed to Singapore’s identity played a far greater role in shaping its society and the science and technology upon which it is founded than hitherto suspected. Moreover, the developments and interactions between Singapore and these Asian cultures took place in an era predating colonial influence. These new approaches may be characterised as dialogical in contrast to traditional Eurocentric perspectives, suggesting that a confluence of different Eastern cultures, along with the Western tradition, gave birth to the Singapore and modern science that we know today.

Dialogical Histories of Singapore

This dialogical perspective on the birth of modern Singapore has been in the making for some time. Emerging from earlier studies, it contextualised the modern trading networks created by Europeans in Asia against the historical backdrop of trading networks developed by Asian pioneers in the previous millennium. In both modern and historical times, these trading networks linked East Asia with South Asia and West Asia, via Southeast Asia.2 To date, the most sustained attempt to reread Singapore’s history and locate its birth in the premodern era is documented in the study Singapore: A 700-Year History by Kwa Chong Guan, Derek Heng and Tan Tai Yong. They argue that the history of Singapore should be contextualised within the larger cycles of maritime history in the Straits of Melaka, and that its beginnings – as narrated in the Sejarah Melayu (Malay Annals) – should be traced back to its founding by Sri Tri Buana in the early 14th century. For nearly a century after its founding, Singapore – then known as Temasek – served as an emporium connecting its Southeast Asian hinterland with the Middle East, India and China.

However, the importance of Temasek as an emporium for the region declined over time. Its fifth ruler had to flee from attacks by the Thai people or the Majapahit empire (or both), and resurrect the emporium in Melaka. As Melaka’s secondary appendage in the 15th century, the fortunes of Singapore declined further when Melaka fell to the Portuguese in 1511 and Singapore came under the influence of the Johor Sultanate. Finally, trade through Singapore collapsed after the Dutch captured Melaka from the Portuguese in 1641 and diverted the Indian-Pacific Ocean trade from the Straits of Melaka to their port in Batavia via the Sunda Straits between Sumatra and Java.3

Singapore’s fortunes revived only after Stamford Raffles, recognising Singapore’s early historical position as an emporium in the 14th century, once again restored it to the centre of trans-Oceanic trade, which flourished as the British Empire increasingly consolidated its hold on India (as an imperial power) and China (through its unequal treaty ports). Singapore became the hub of these trade exchanges, and the premier entrepot for the Southeast Asian region.4

There are other historians who also endorse a dialogical account of the birth of Singapore. In their study Singapore: A Biography, Mark Ravinder Frost and Yu-Mei Balasingamchow write:

More significantly, John Miksic has argued that Raffles, as a scholar of Malay history, was profoundly aware of Temasek’s previous role as the emporium that preceded and laid the groundwork for trade in Melaka. It led him to select Singapore as the site for the British port in Southeast Asia.

Dialogical Histories of Modern Science

The pioneering work that paved the way for dialogical histories of science was Joseph Needham’s monumental series Science and Civilization in China.5 Needham revealed the significant contributions made by China to modern science and technology, including the invention of gunpowder, printing, the compass and paper. Over the five decades since Needham began his study, others have been inspired to broaden the scope of his project in two directions. Firstly, there has been increasing documentation of not just Chinese, but also Indian and Arabic-Islamic contributions to modern science.6 Secondly, this has in turn led to a greater appreciation of how philosophical, theoretical and technological contributions from China, India and the Islamic world came to interact and combine with European tradition to form what we know as modern science today. Science is now seen as profoundly shaped by intercultural dialogue.7

The Copernican Revolution, often associated with the birth of modern science, best illustrates the significance of intercultural dialogue in science. The revolution began in 1543, when Copernicus proposed that the sun, moon and planets were not revolving around a stationary earth, but rather the earth, moon and planets were revolving around the sun. To accommodate this heliocentric (sun-centred) theory, scientists had to develop entirely new mathematics, physics and cosmology, culminating more than 140 years later in 1684 in Newton’s theory of gravitation and his laws of motion.

Historians in the past had often assumed that the Copernican Revolution built only upon the achievements of ancient Greek mathematics, physics and astronomy. However, more recent historical evidence suggests that the Copernican Revolution also drew on developments that took place earlier in the Islamic, Indian and Chinese astronomical traditions. Especially significant were the theoretical, philosophical and cosmological ideas associated with the Maragha School of astronomy in the Arabic world, the Kerala School of astronomy in India, and the infinite empty-space theory espoused by the neo-Confucian court astronomers of the Ming dynasty. The fusion of ideas from ancient Greece and these three schools made possible the Copernican Revolution.8

The Maragha School first emerged in the 14th century as a critique of the inadequacies of the geocentric theory, which the Arabs had inherited from the ancient Greeks. The Greek theory, which was central to the school, was satisfied with making mathematical predictions without offering a realist physical model of the universe. Conversely, the Maragha School achieved its objective with Ibn al-Shatir and his ingenious deployment of two new geometrical theorems discovered by Arabic mathematicians – the Urdi Lemma and the Tusi Couple. Despite the Maragha School’s sustaining of the earth-centred vision of the planetary system it had inherited from the ancient Greeks, its theoretical innovations paved the way for Copernicus’ heliocentric theory. It made it possible for Copernicus to develop a credible mathematical model in which the sun, rather than the earth, was made the centre of the planetary system. Although astronomers before Copernicus had been aware of the possibility of such a sun-centred model, they were unable to articulate it mathematically as a viable alternative without the new computational methods developed by the Maragha School of astronomers.9

Similarly, the Kerala School of astronomy developed powerful mathematical methods to express not only trigonometric functions as infinite series expansions, but also arrive at some proto-ideas of the calculus. There is evidence that these discoveries may have inspired modern European thinkers to build on these and develop the powerful ideas of the calculus that were integral to consolidating the Copernican revolution through Newton’s theory of gravitation.10

Equally significant was the contribution of Chinese astronomical and cosmological ideas to modern astronomy. When the European Jesuits made contact with Chinese astronomers in the late 16th century, they found many of the beliefs and ideas common to the Chinese absurd. The Europeans considered space finite and filled with air, but the Chinese believed in an infinite empty space. The Europeans believed the heavens to be unchanging except for the rotational motions of the sun, moon, planets and stars around the earth, but the Chinese believed the heavens to be ever-changing, with comets and meteors appearing and disappearing. Although Europeans had seen comets and meteors, they interpreted them as exhalations from the earth that had reached the upper atmosphere – likening them to meteorological phenomena like lightning and clouds rather than astronomical ones. These Chinese ideas would eventually be incorporated into modern astronomy with the Copernican Revolution.11

The Birth of Singapore and the Birth of Modern Science: Strange Parallels

A comparison of the dialogical histories of the birth of Singapore and the birth of modern science reveals a number of striking parallels. First, consider the cultures that are said to have come together from the outside at the birth of Singapore in revisionist 14th-century histories. Apart from the regional culture of Southeast Asia, others might include the Chinese, the Indian and the Islamic. In fact, it is likely that the last ruler of Singapore converted to Islam before leaving to found Melaka at the end of the 14th century. What is striking is that these cultures were also the ones whose astronomical traditions contributed to the advent of the Copernican revolution in Europe, which ushered in modern science.

Second, the period that saw the founding of Temasek in the 14th century also coincided with the establishment of the Maragha School in the Arabic world and the Kerala School in India. Although the theory of infinite empty space had been proposed in China earlier, it only became accepted as the dominant view in Chinese astronomy during the Ming dynasty in the 14th century.

Can we explain these strange parallels? Why are the cultures that came together at the time of Singapore’s birth in the 14th century also the cultures that came together at the genesis of modern science? A likely explanation is that around the 14th century, the maritime Silk Road connecting the Middle East, India, Southeast Asia and China became a significant corridor of trade and, possibly, intellectual exchange. Increasing wealth and the need to traverse vast distances across the oceans also led to astronomical studies, which were crucial for navigation. It is therefore not surprising that the era saw important astronomical discoveries made in China, India and the Arabic-Muslim world that came to be fused together with the emergence of modern science and astronomy in 17th-century Europe.12

Finding the Future in the Past: Rethinking National Education and Science Education

It is widely acknowledged that among the many concerns in Singapore education, two of the most critical pertain to national education and science.13 National education is concerned with fostering a common identity among the various cultural and ethnic groups in the nation-state in order to sustain social peace and harmony. Science’s concern is nurturing a culture of scientific innovation and creativity that goes beyond the rote-learning model that has characterised education in the past. However, strategies that have been formed to deal with these problems often presume Eurocentric conceptions of the birth of modern Singapore and modern science. Such strategies may have to be reconsidered in light of the more recent dialogical histories of both the origin of Singapore and that of modern science.

The Eurocentric account of Singapore’s history suggests that the coming together of the diverse cultures of Singapore was an incidental by-product of the European imperative set in motion by Raffles in 1819, and that these cultures must find ways to form a common identity. These cultures also do not have any deep history of coexisting with each other. National education must therefore find ways of moving away from these separate pasts in order to forge a common future.

Similarly, the Eurocentric history of science suggests that in order to nurture a culture of innovation and creativity in science and technology we must break away from the rote-learning that is assumed to characterise Chinese, Indian and Malay-Islamic traditional education. It seems that the overarching assumption is that to nurture creativity, Singaporeans must learn from the cultures that have shown visible achievements in the modern era, namely Europe and the United States.

However, dialogical histories of both Singapore and modern science also suggest that the answers may be found in the past. In the first place, forging unity out of diverse cultures may well be central to Singapore’s success as an emporium in the 14th century and its continued success as a global city today. The issue is not about creating a common identity out of separate identities by fusing cultures together, but discovering how the different identities that make up Singapore’s culture made Singapore’s success over its 700-year history possible, particularly by enabling it to draw upon diverse cultural resources to advance trade and promote development.

Nurturing scientific creativity need not involve repudiating the scientific traditions in Singapore’s heritage as an Asian civilisation. After all, if modern science drew on the resources of the Chinese, Islamic and Indian cultures at its dawn, then these cultures did create reservoirs of knowledge to advance science. We could therefore ask: What can we learn about creative and innovative thinking from the different Asian cultures in their time of pioneering achievements – in the premodern era?

Clearly, dialogical histories of Singapore and modern science suggest that we need not turn away from Singapore’s multicultural heritage to find solutions to the concerns of designing a national education curriculum that unites, and a science education that nurtures creativity and innovation. We may also find solutions by studying how our different cultures – Chinese, Malay-Islamic and Indian – engaged in intercultural dialogue to produce Singapore’s successful and globalised emporium culture and the scientific tradition that drives it today.

Visiting Senior Research Fellow

Institute of Southeast Asian Studies

REFERENCES

Arun Bala, The Dialogue of Civilizations in the Birth of Modern Science (Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, 2010). (Call no. RSING 509 BAL)

Arun Bala, “Eurocentric Roots of the Clash of Civilizations: A Perspective From the History of Science,” in Rajani Kannepalli Kanth, The Challenge of Eurocentrism: Global Perspectives, Policy and Prospects (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2009), 9–23.

George Gheverghese Joseph, The Crest of the Peacock: Non-European Roots of Mathematics (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2000)

George Saliba, Islamic Science and the Making of the European Renaissance (Cambridge: The MIT Press, 2007)

Janet L. Abu-Lughod, Before European Hegemony: The World System A.D. 1250–1350 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1989) (Call no. RCLOS 330.94017 ABU)

John M. Hobson, The Eastern Origins of Western Civilisation (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004). (Call no. R 909.091821 HOB)

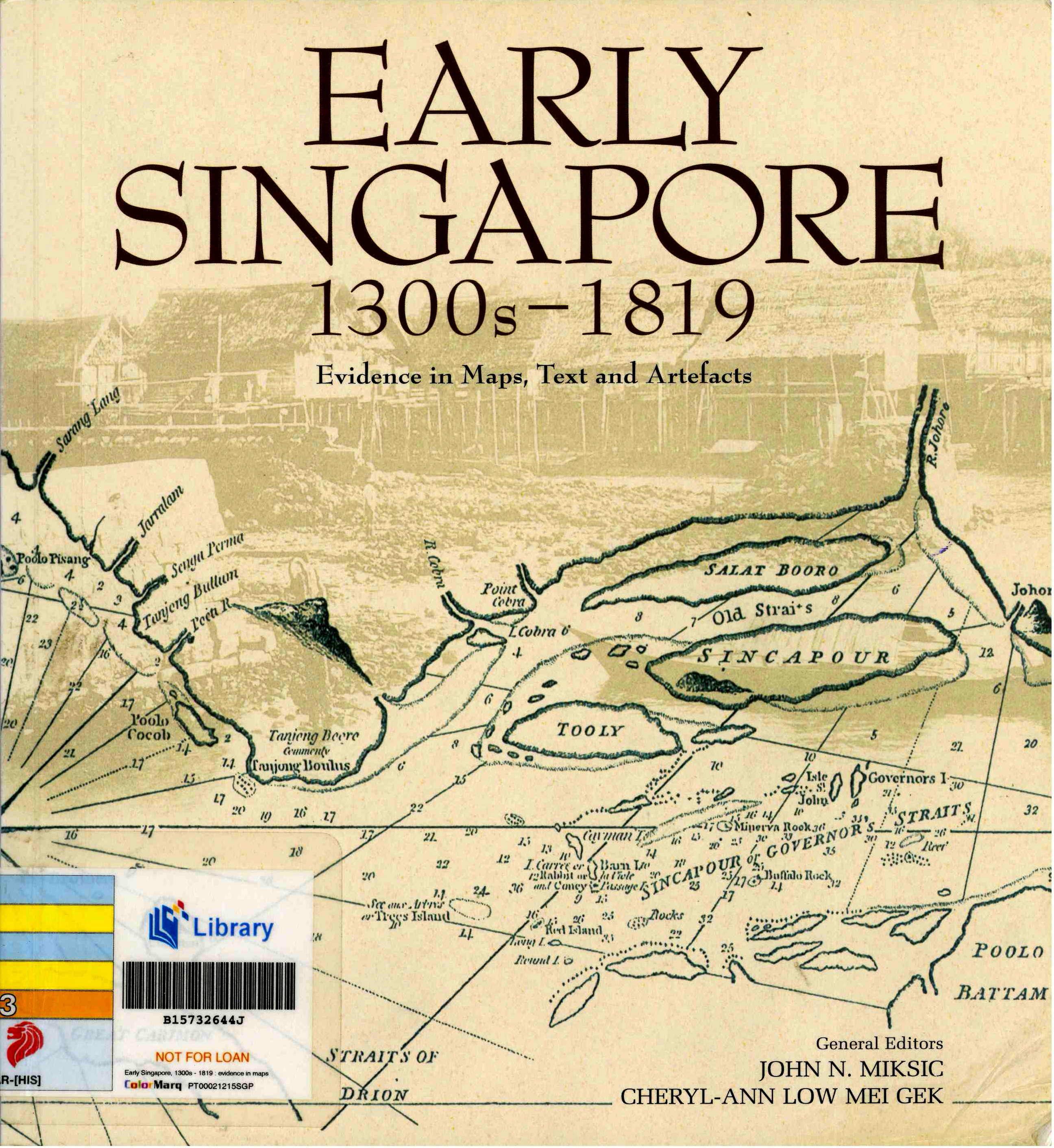

John N. Miksic and Cheryl-Ann Low Mei Gek, eds., Early Singapore, 1300s–1819: Evidence in Maps, Text and Artefacts (Singapore: Singapore History Museum, 2004). (Call no. RSING 959.5703 EAR)

Joseph Needham, Science and Civilisation in China, vols. 1 and 2 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1991). (Call no. RCLOS 509.51 NEE)

Kwa Chong Guan, Derek Heng and Tan Tai Yong, Singapore, a 700-Year History: From Early Emporium to World City (Singapore: National Archives of Singapore, 2010). (Call no. RSING 959.5703 KWA)

Mark Ravinder Frost and Yu-Mei Balasingamchow, Singapore: A Biography (Singapore: Editions Didier Millet Pte Ltd, 2009) (Call no. RSING 959.57 FRO)

Rajani Kannepalli Kanth, The Challenge of Eurocentrism: Global Perspectives, Policy and Prospects (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2009)

NOTES

-

For a critique of this approach to the writing of Singapore history, which began in colonial times but continued into the postcolonial era, see Kwa Chong Guan, Derek Heng and Tan Tai Yong, Singapore, a 700-Year History: From Early Emporium to World City (Singapore: National Archives of Singapore, 2010), 1–8. (Call no. RSING 959.5703 KWA). Their revisionist account traces earlier beginnings from the 14th-century founding of Temasek at the mouth of the Singapore River. Similar efforts to locate history by beginning with Temasek can be found in Mark Ravinder Frost and Yu-Mei Balasingamchow, Singapore: A Biography (Singapore: Editions Didier Millet Pte Ltd, 2009) (Call no. RSING 959.57 FRO) and John N. Miksic and Cheryl-Ann Low Mei Gek, eds., Early Singapore, 1300s–1819: Evidence in Maps, Text and Artefacts (Singapore: Singapore History Museum, 2004). (Call no. RSING 959.5703 EAR) ↩

-

These studies include Wolf (1982), Janet L. Abu-Lughod, Before European Hegemony: The World System A.D. 1250–1350 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1989) (Call no. RCLOS 330.94017 ABU) and John M. Hobson, The Eastern Origins of Western Civilisation (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004). (Call no. R 909.091821 HOB) ↩

-

Kwa, Heng and Tan, Singapore, a 700-Year History, 79–81. ↩

-

See “Raffles and the Establishment of an East India Company Station on Singapore,” ch. 7, in Kwa, Heng and Tan, Singapore, a 700-Year History. ↩

-

Especially significant in this regard are the first two overview volumes published in 1954 and 1956. They give the philosophical, historical and sociological background for the phenomenal growth of science in Chinese civilisation from the early Han dynasty to the 16th century. Although Chinese science continued to grow thereafter, it was quickly overtaken by the more rapid growth of modern science. See Joseph Needham, Science and Civilisation in China, vols. 1 and 2 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1991). (Call no. RCLOS 509.51 NEE) ↩

-

See George Gheverghese Joseph, The Crest of the Peacock: Non-European Roots of Mathematics (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2000) and George Saliba, Islamic Science and the Making of the European Renaissance (Cambridge: The MIT Press, 2007) ↩

-

This dialogical fusion of modern scientific knowledge from many cultural traditions is documented in the field of mathematics by Joseph, 2000; in technology by Hobson, The Eastern Origins of Western Civilisation; and in mathematical astronomy by Arun Bala, The Dialogue of Civilizations in the Birth of Modern Science (Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, 2010). (Call no. RSING 509 BAL) ↩

-

See Bala, The Dialogue of Civilizations for a more detailed account of how different mathematical astronomical traditions from ancient Greece, the Arab world, China and India came to be combined together by modern European thinkers to give birth to the astronomical revolution that jump-started modern science. ↩

-

For more details, see Saliba, Islamic Science and the Making of the European Renaissance. ↩

-

A defense of these claims can be found in Bala, The Dialogue of Civilizations, 68–78. ↩

-

For more elaborate discussion of these issues, see Bala, The Dialogue of Civilizations, 131–44. ↩

-

A good and influential study of these maritime Silk Road linkages is Abu-Lughod, Before European Hegemony. ↩

-

For more information see the Singapore Ministry of Education site, especially https://www.moe.gov.sg/education-in-sg/our-programmes/national-education on National Education and https://www.moe.gov.sg/education-in-sg/desired-outcomes#:~:text=Be%20innovative%20and%20enterprising.,have%20an%20appreciation%20for%20aesthetics on Desired Outcomes of Education. ↩