The Growth of Imagination in Singapore Children’s Literature in English (1965–2005)

Lee Kong Chian Research Fellow Noel Chia Kok Hwee traces the trajectory and importance of imaginative Singapore children’s literature in English.

My research is on imaginative Singapore children’s literature in English (SCLE) with an emphasis on children’s prose fiction, which can be divided into fantasy and realism (see Lynch-Brown & Tomlinson, 2008; Tomlinson & Lynch-Brown, 2010). Both fantasy and realism involve two literary processing channels1 – imagination and verisimilitude, which provide a link between the world grounded in reality and the meta-world in our minds. Through this meta-cognitive link, readers are able to experience the episodes as described in the stories and through the characters.

The term imagination is defined as that literary process of the mind to generate mental images of objects, states or actions not felt or experienced by the senses. Imagination is usually synonymous with “fancy, and commonly opposed to the faculty of reason, either as complementary to it or as contrary to it”.2 According to Sewall (1999) and Roth (2004), imagination helps bridge readers and their environment to create meaningful experiences and understanding of knowledge. It is a fundamental facility through which readers make sense of the world (Norman, 2000; Sutton-Smith, 1988) and also plays an important role in the learning process (Egan, 1992; Norman, 2000).

The other term verisimilitude (also known as truth-likeness) is the semblance of truth or reality in literary works or the literary principle that requires a consistent illusion of truth to life. It encompasses both the exclusion of improbabilities (as in realism) and the careful disguising of improbabilities in nonrealistic works.3 Verisimilitude also refers to the other literary process that is “often invoked in fantasy and science fiction inviting readers to pretend such stories are true by referring to objects of the mind such as fictional books or years that do not exist apart from an imaginary world” (Roth, 2004, p. 10). This imaginary world is also known as meta-world (Chia, 1991).

By seeing the world around them in new ways and by considering ways of living other than their own, children increase their ability to think divergently. Stories often map the divergent paths that our ancestors might have taken or that our descendants might someday take. “Through the vicarious experience of entering a world different from the present one, children develop their imaginations. In addition, stories about people, both real and imaginary, can inspire children to overcome obstacles, accept different perspectives, and formulate personal goals” (Lynch-Brown & Tomlinson, 2008, p. 5).

Moreover, children’s books with a high degree of imaginativity4 provide the highest level of reader enchantment, which is an endogenous process that stimulates a reader’s mind. This process throws readers into that meta-world where they can take part in any adventure, journey or exploration (Chia, 2004). It makes readers want to go on and not stop reading. In this sense, they have gone beyond automaticity. They are now a part of that story and have become either like avatars participating in the fantasy world, or like morpheus watching the events gradually unfolding. The final outcome is a sensitive awareness of imaginativity in children’s literature.

Promoting SCLE by encouraging reading for pleasure among our children demands special effort in translating written language or print into meta-worlds (or realms of fantasy) – “worlds within worlds whose reality is primarily in the mind” (Roloff, 1973). Though a meta-world is a reality only within the mental boundaries of the mind, the existence of such realms can be readily accepted by most readers (Chia, 1991, 1996). Regardless of how peculiar or remote it may seem, readers should be sufficiently convinced that the meta-world really exists – they must believe in it and need to suspend their disbelief (just as if they were role-playing). This is the power of imagination that good children’s literature can help promote.

The Changing Landscape (1965–2005)

SCLE evolved as ideas surrounding it and perspectives changed. In the past, SCLE “was largely concentrated on reading materials rather than fiction proper, [whereas] the current trend shows a move towards better fiction though it is largely folktales and picture book fiction” (National Library Board, 2005, p. 3). For SCLE to attract a wider readership there is a need for our writers, illustrators and/or publishers to expand the scope of imagination.

My original research surveyed the changing landscape of SCLE from 1965 to 2005, using the Imaginativity Rating Scale (IRS) to measure changing levels of imaginativity. However, my focus in this article is the descriptive findings of the study; I reserve its quantitative findings for another paper. I examine the development of SCLE over time, looking for that which “would ideally represent the authentic voice of the Singapore child” (Hassan, 2006, p. 16), and the various significant historical events that affected it. I have divided the 40 years into five periods: the Didactic Period (1960s), the Pioneering Period (1970s), the Emergent Period (1980s), the Progressive Period (1990s) and the New Millennium (2000s)

The Didactic Period (1960s)

One of the early roadblocks to the growth of Singapore children’s literature has been its poor commercial viability, due to the small local market. As early as 1966, then Minister for Education Ong Pang Boon said:

A scan of the SCLE available during the 1960s at the Lee Kong Chian Reference Library reveals that basal readers were used in many English-medium schools and outnumbered quality children’s fiction on all counts. This reflected the Singapore government’s policy during this period “to get the general populace to put a premium on education, and the habit of reading began to be developed as part and parcel of the learning process” (Kong & Tay, 1998, p. 8). Besides, the parents, being very pragmatic, “look only for books ‘useful’ in boosting their children’s school performance” (Khoo, 1992, p. 101).

I was able to identify only one trade book published during this period: Sylvia Sherry’s Street of the Small Night Market (1966). Others were merely basal readers such as Federal Supplementary Readers Third Year (Book 3) (1961), Federal Readers Book 1 (1963) and Structural English Course Reader 4 (1968). It was in a third course reader that I found an interesting story, The King of Fishes (1968), by Chia Meng Ann and Chia Hearn Chek. “Although the literature addressed reading discovery, it was positioned to address reading needs first and often the tone of the materials was didactic if not dull” (National Library Board, 2005, p. 2).

The Pioneering Period (1970s)

A serious effort to promote the writing of children’s books began with the Workshop on Children’s Books “organised by the National Book Development Council of Singapore (NBDCS) to coincide with a week’s visit of Ivan Southall, an Australian children’s writer, at its invitation from 8–15 October, 1971” (Anuar, 1972, p. 3). In the opening speech, the late principal of the Teachers’ Training College, Dr Ruth Wong, stressed the role of books for children:

In other words, books can provide a glimpse of imagination experienced by avid readers if they immerse themselves into that fictive world.

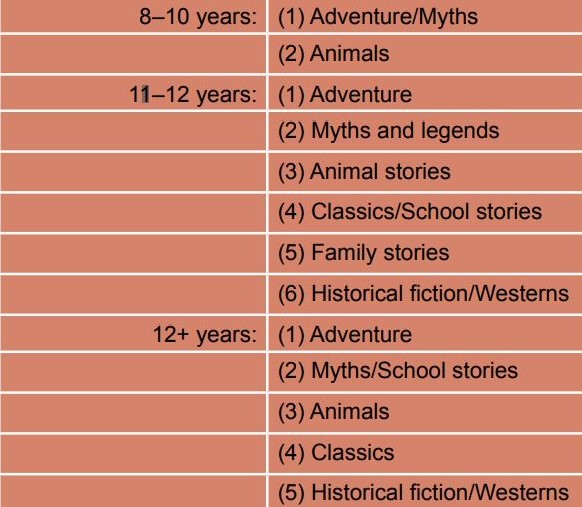

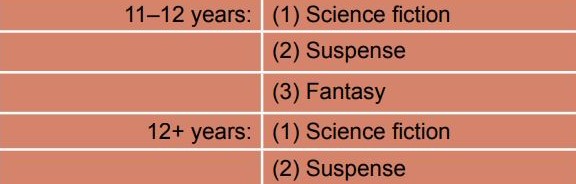

Folktales, fables and basal readers dominated SCLE in the 1970s. Didacticism from the previous period was also carried over into this period. According to Nair et al. (1977), a survey study done by the National Library covering three age groups showed their reading preference in the following order of appreciation (p. 11):

The adventure story was the hot favourite for all three age groups during that time, followed by myths and legends. According to Nair:

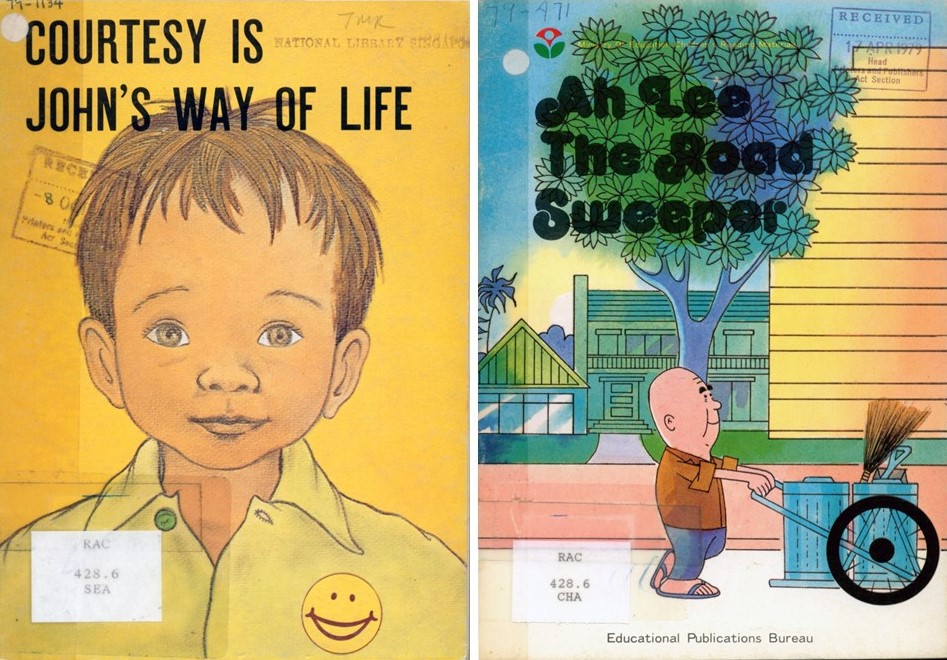

In the 1970s, children’s books tended to adopt the themes of national campaigns; some of these included the ban on firecrackers during the Lunar New Year; Keep Singapore Clean; bilingualism in schools; multiracial and multicultural identity and so on (Lim, 2009). Hence, it is not surprising to find many basal readers such as the Active Reader series (Federal Publications, 1970) and New Way Readers series (Pan Pacific, 1978) propagating these national agendas. Examples of such books include Ah Lee the Road Sweeper (1979), The Singapore Youth Festival (1975) and Courtesy Is John’s Way of Life (1979). There are other books devoted to the interests and culture of Singapore as an independent nation that date back to Srivijayan times in the early 14th century, such as Chia Hearn Chek’s The Redhill (1974) and The Raja’s Crown (1975).

One reason why SCLE during this period lacked imaginativity was also partly due to children’s reading abilities and power of imagination. Mature or sophisticated readers were few. Literary genres such as fantasy, suspense and science fiction (FSSF) that appeal to creative imagination, curiosity or wonder had limited appeal to our young readers then (Nair et al., 1977). From the reading survey done by the Children’s Services of the National Library in 1976, the youngest group of readers in Singapore did not read books in the FSSF category at all, while the other two groups showed the following preferences (Nair et al., 1977, p. 11):

It should be noted that titles in the science fiction category were of limited availability compared to adventure stories and myths and legends (in the ratio of 9:99). Nair et al. (1977) explained why FSSF had such poor appeal:

Another important contributing factor during the 1970s was that not all children were attending English-medium schools. This might explain why Singapore writers rarely ventured into fantasy, suspense and science fiction, and the publishers were not keen to publish books of this category.

During the 1970s, important changes had been made to the primary school curriculum. The emphasis in the English syllabus was on language enrichment through storytelling, poetry, creative writing and educational drama. The new enrichment programme created excellent opportunities for the publishing of children’s literature in Singapore (Girvin, 1976).

At a seminar on the role of educational materials in Singapore schools, held in 1973, the late Marie Bong, principal of Katong Convent, emphasised the urgent need for a variety of interesting books that would appeal to children so as to expose them “to the rich resources of language and stimulate them to read and write stories of their own” (cited in Girvin, 1976, p. 6). This exposure was seen as vital and schools began to break away from the rigid textbook course of study, but success of the system, as Girvin (1976) argued, “will depend on there being sufficient supply of general literature for children to meet the demands at each level of the child’s understanding. Publishers must answer these needs” (pp. 6–7).

The Emergent Period (1980s)

Strictly speaking, SCLE only emerged in the 1980s, as evidenced by two national reading surveys, one conducted in 1980 and the other in 1988. The survey findings showed an increase in readership over that period as well as changing reading habits and tastes. However, few were reading books written by Singapore writers and many simply responded with “don’t know” to the questions asked about local writers and their writings (National Book Development Council of Singapore, 1981). The Report of the Committee on Literacy Arts (Ministry of Community Development, 1988) pointed out that Singaporeans tended to have a utilitarian attitude towards reading. They read to increase general knowledge and to keep abreast of current affairs as well as to pass tests and examinations, not for pleasure.

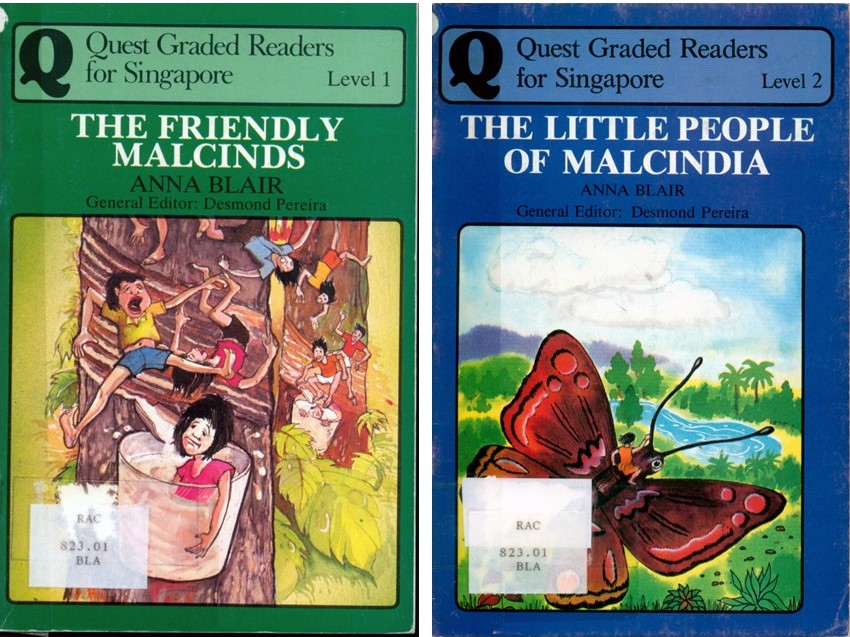

Despite the publication of books in the genre of imaginative children’s fiction such as The Friendly Malcinds (Blair, 1982) and The Little People of Malcindia (Blair, 1985), these works often read as forced and artificial in their attempts “to create a Singaporean multi-ethnic identity by incorporating qualities from each of the three main races in Singapore” (Khoo, 1990/91, p. 21). They were still lacking the kind of real imagination (also known as imagining or fantasising), which J.S. Mill (cited in Leavis, 1950), describes as that which enables us to voluntarily conceive the absent as if it were present, the imaginary as if it were real, and to clothe it in the feelings which, if it were indeed real, it would bring along with it. “This is the power by which one human being enters into the mind and circumstances of another” (Chia, 1991, p. 22) in somewhat a similar fashion like the main protagonist, Jake Scully, who entered into the body of an avatar in order to be in close contact with the Na’vi tribe, shown in the recent Oscar-award-winning blockbuster movie Avatar and described in James Cameron’s book entitled Avatar: The Na’vi Quest (2009).

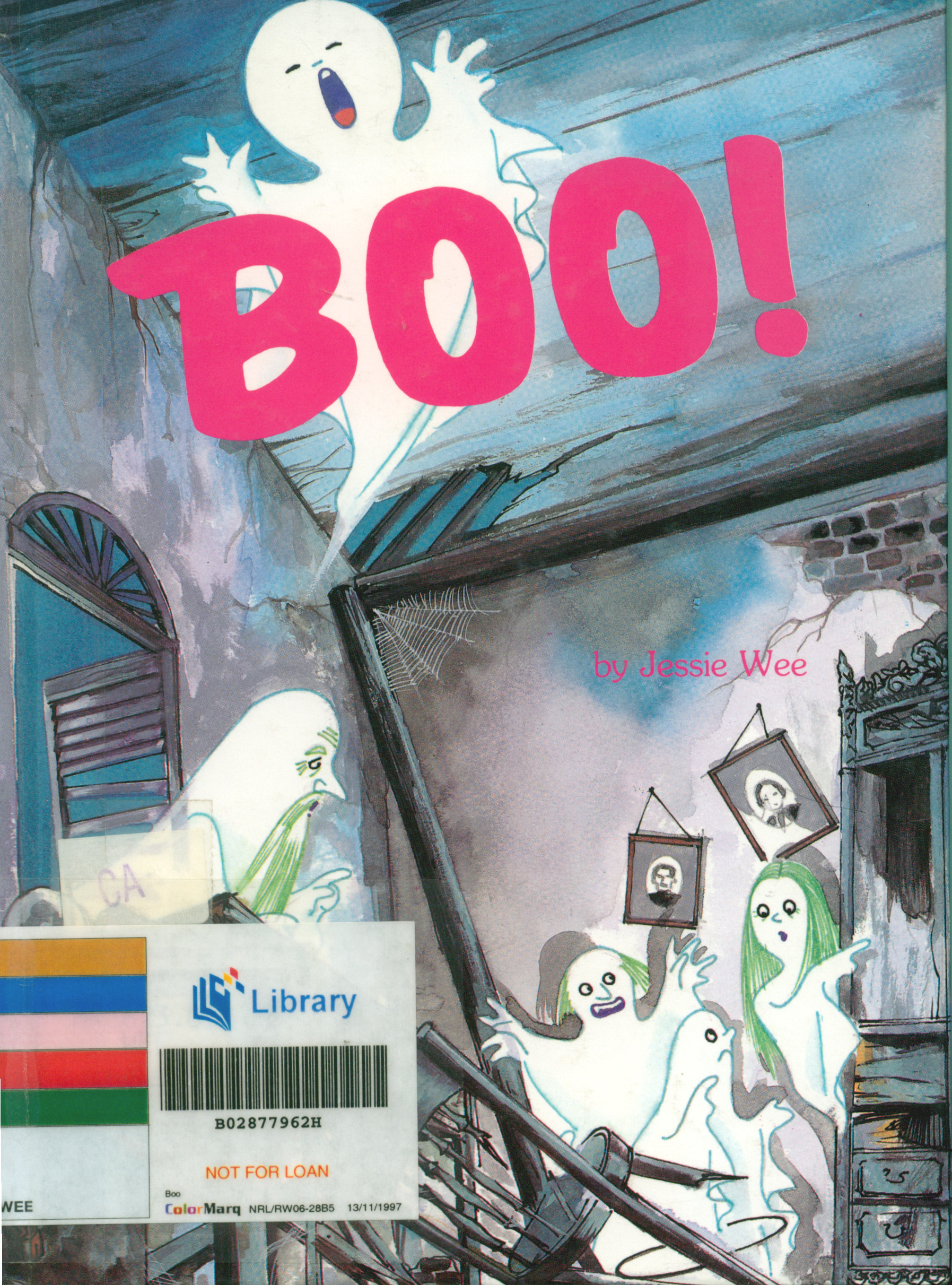

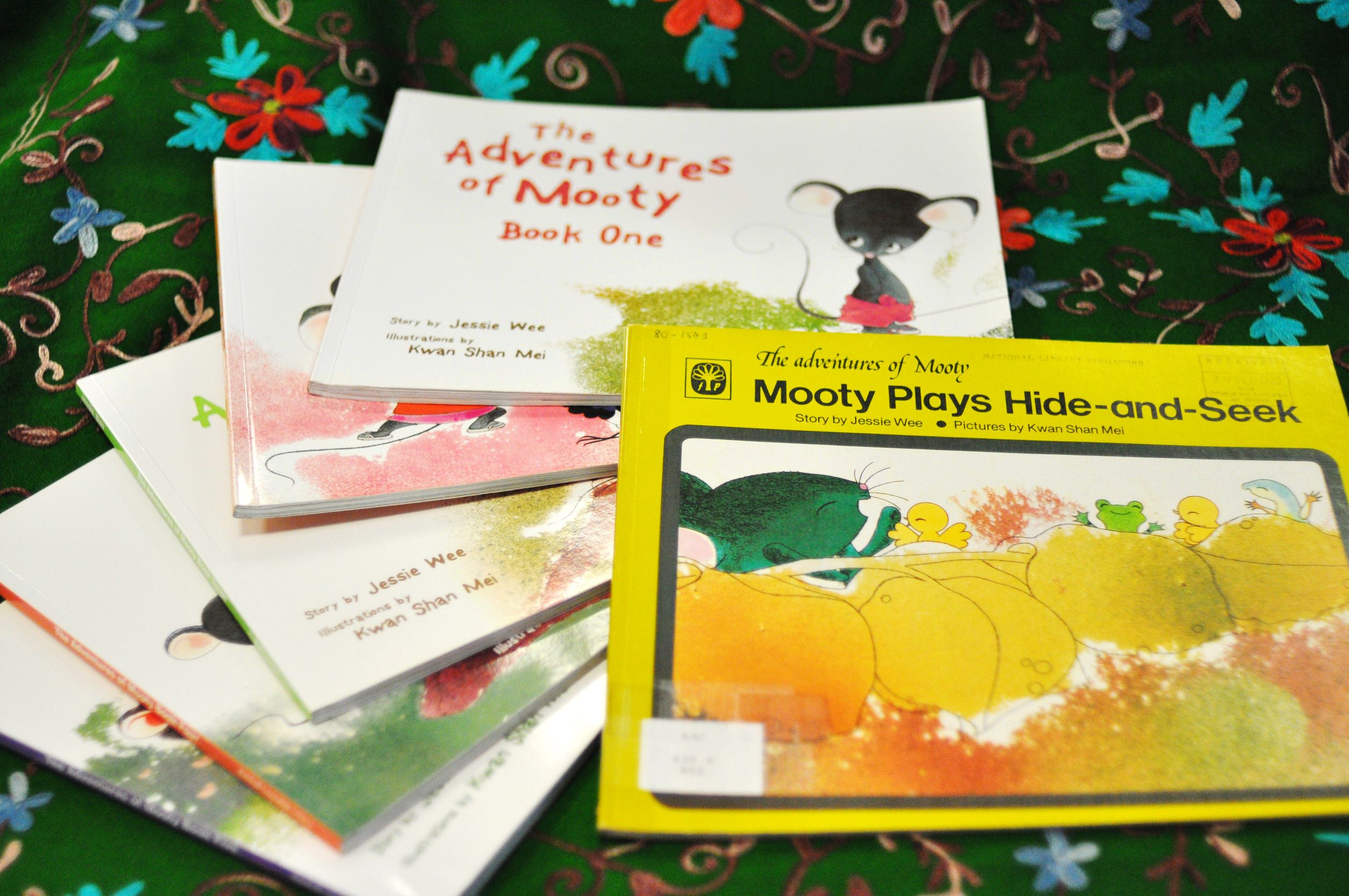

However, books published in the 1980s showed marked improvements in visual presentation. Publishers explored the use of quality colours and illustrations for children’s books, such as Jessie Wee’s Boo! (1984), which has an attractive cover illustration. Jessie Wee, undeniably a forerunner in writing for children in Singapore, is a significant contributor to SCLE. Her series, The Adventures of Mooty (1980,) has been popular from the time it was released and set a milestone in creative Singapore children’s literature. Wee’s focused attempt to write children’s stories in the context of Singapore is characteristic of her inimitable writing style.

During this period, publishers would generally publish according to perceived market demand, such as catering “to the buying preference of parents for ‘useful’ reading by producing (1) folktales because these help children to learn about their culture, (2) stories with a moral so that children learn good values, and (3) supplementary readers with comprehension exercises so that children can improve their reading skills” (Khoo, 1990/91, p. 20).

The Progressive Period (1990s)

Although still very much in its infancy, the 1990s witnessed a relative boom in locally authored SCLE. According to Wee (1990/91), “it is the passionate belief that our children in Singapore need stories they can identify with, stories they can call their own” (p. 38). This is the driving force for many of the Singapore writers of children’s fiction. SCLE took on a contemporary edge with an increasing public interest and acceptance, and publishing output improved as more writers entered the scene in the 1990s.

At the beginning of the 1990s, there was a seminar, In Search of a Singapore Children’s Literature, 6–7 September 1990, organised by the National Book Development Council of Singapore (NBDCS) to create “public awareness of the need for good children’s books” (Anuar, 1990/91, p. 1). Anuar (1990/91) argued for the need to take writing for children as seriously as writing for adults, adding that “children are part of the human race, not a separate species. And children’s literature is or should be part of a country’s literature” (Anuar, 1990/91, p. 1).

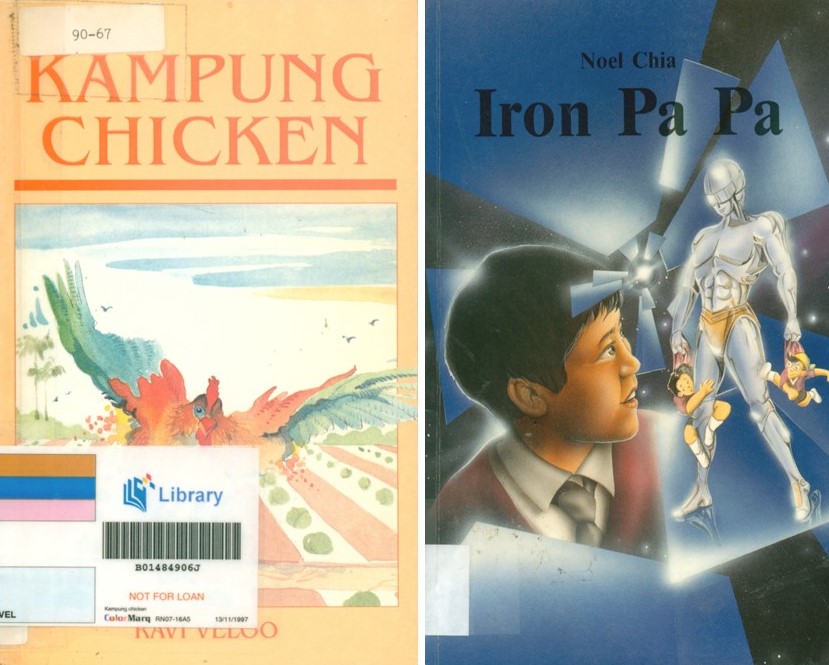

A new crop of writers and publications appeared on the literary scene during this period, such as Ravi Veloo with Kampung Chicken (1990), Noel Chia with Iron Pa Pa (1993) and Ramanathan Chandran with I Have Touched the Moon! (1997). It is also during this period that Singapore witnessed a boom in publications of SCLE. Singh (1993/94) reported that “[t]he situation… seems remarkably different in terms of the quantitative progress our fiction has witnessed in the passing years. Almost every bookshop, even the mama stalls which usually stock only magazines, carries [sic] Singapore titles” (p. 21). There were also a number of new authors who paid out of their own pockets to publish their books rather than go through a publisher. However, the quality of these children’s fiction books (e.g., editing and illustrations) was poor and mostly in the genre of ghost and horror stories.

In 1993, a reading survey conducted by the National Library found that “the percentage of literate persons who had read just one book in the last 12 months had decreased by 7% from 57% down to 50% over the last 13 years” (Butterworth, 1994, p. 5). Despite a drop in library membership, Koh (1994) reported that the fostering of the reading habit among children was being given a higher priority and had achieved some success. Figures from the National Library showed that loans of children’s books increased from 1.63 million in 1980 to 4.79 million in 1993, and “the expansion of the scheme to set up neighbourhood children’s libraries in the void decks of HDB flats… will give greater access to quality collections” (Koh, 1994, p. 4).

In other words, Singapore writers had to work even harder, tapping into their inspiration, imagination and creativity to produce higher, if not superb, quality children’s books like that of Michael Ende’s Die Unendliche Geschichte [translated from German: The Neverending Story] (1979) and Rick Riordan’s Percy Jackson and the Olympians (2008) series. Good SCLE should be able to enchant young readers into wanting more of such books; establishing quality SCLE begins the creation of the sense of one’s own literary landscape in our children (Lee, 1990/91).

This is also echoed by Singh (1993/94), who argued that “the years of following [from 1993 onwards] should see an increase in the output of ‘popular’ fiction; e.g., ghost stories, sensational stories of one description or another” (p. 21). He cautioned:

The New Millennium (2000s)

Since the beginning of the 21st century, SCLE has taken a more international perspective as more discerning and creative writers and illustrators enter the writing and publishing industry. The biennial Singapore Writers Festival, a major literary event in Singapore since the turn of the 21st century, has gained prominence in both domestic and regional literary landscapes. The writers’ festival is now restructured into an annual affair, attracting not only local published and aspiring writers of children’s fiction and adult fiction but also writers from overseas.

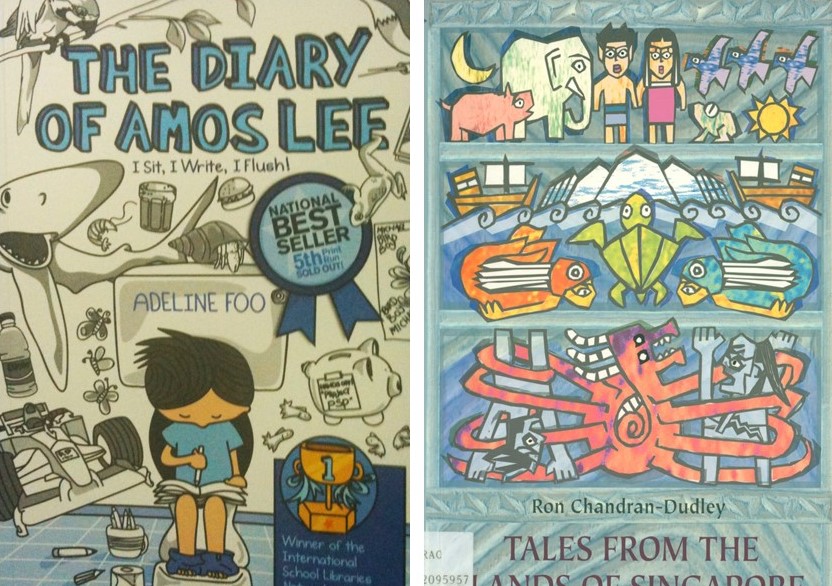

According to Ng (2010a), “judging by sales, children’s books are a lucrative field and more Singapore writers are making their mark in it” (p. 6). Today, children’s storybooks are selling better than Singapore adult novels. For instance, James Lee’s Mr Midnight series of illustrated horror stories has sold more than two million copies in Asia alone, and is now on its 67th book. Other children’s storybook successes, although on a smaller scale, are by writers such as Adeline Foo, whose book Diary of Amos Lee (2007) is not included in this study, has sold about 40,000 copies here.

One reason for the success of local children’s literature is that parents today are more willing to spend on their children’s education and “the young ones are also more willing to give new and unknown writers a chance” (Ng, 2010a, p. 6). Besides, parents have also found an increased attraction to the Asian context of Singapore writers’ stories. Another reason is that first-time writers of children’s fiction can now seek financial assistance through the First Time Writers and Illustrators Publishing Initiative. Launched in 2005, this initiative is jointly organised by the Media Development Authority and the National Book Development Council of Singapore (Media Development Authority, 2005). SCLE is still evolving slowly and gradually in terms of its quality and reader ownership. To quote Jessie Wee (1990/91), “children in Singapore need stories they can identify with, stories they can call their own” (p. 39).

Conclusion

Most books published in the 1960s were not trade books but basal readers whose aim was to improve the English proficiency of Singaporeans in both spoken and written forms. Hence, during the Pioneering Period (1970–79), it was an uphill task for writers of SCLE to be recognised, their creative works taken seriously by the publishers and appreciated by readers at large. SCLE only really emerged in the 1980s (Khoo, 1990/91) when more writers began to write for children. Although many of these books were badly written or poorly edited, it was a good sign that teachers and parents were beginning to take notice of locally published books for children. One big challenge during that period was that many teachers were reluctant to encourage their students to read local children’s literature because of its poor quality of written English. In fact, this problem persisted into the 1990s.

Between the late 1980s and the beginning of the 1990s, the Singapore book market witnessed a sudden increase in the number of new books published locally by new publishers such as VJ Times and Flame of the Forest. With more new writers trying their hand at writing for children, the local book scene saw a wider range of both new children’s fiction and nonfiction titles. It was also during the period 1990–99 that more new writers had their works printed through established publishers such as Educational Publications Bureau and Times Book International, although there were also a few others who chose to self-publish.

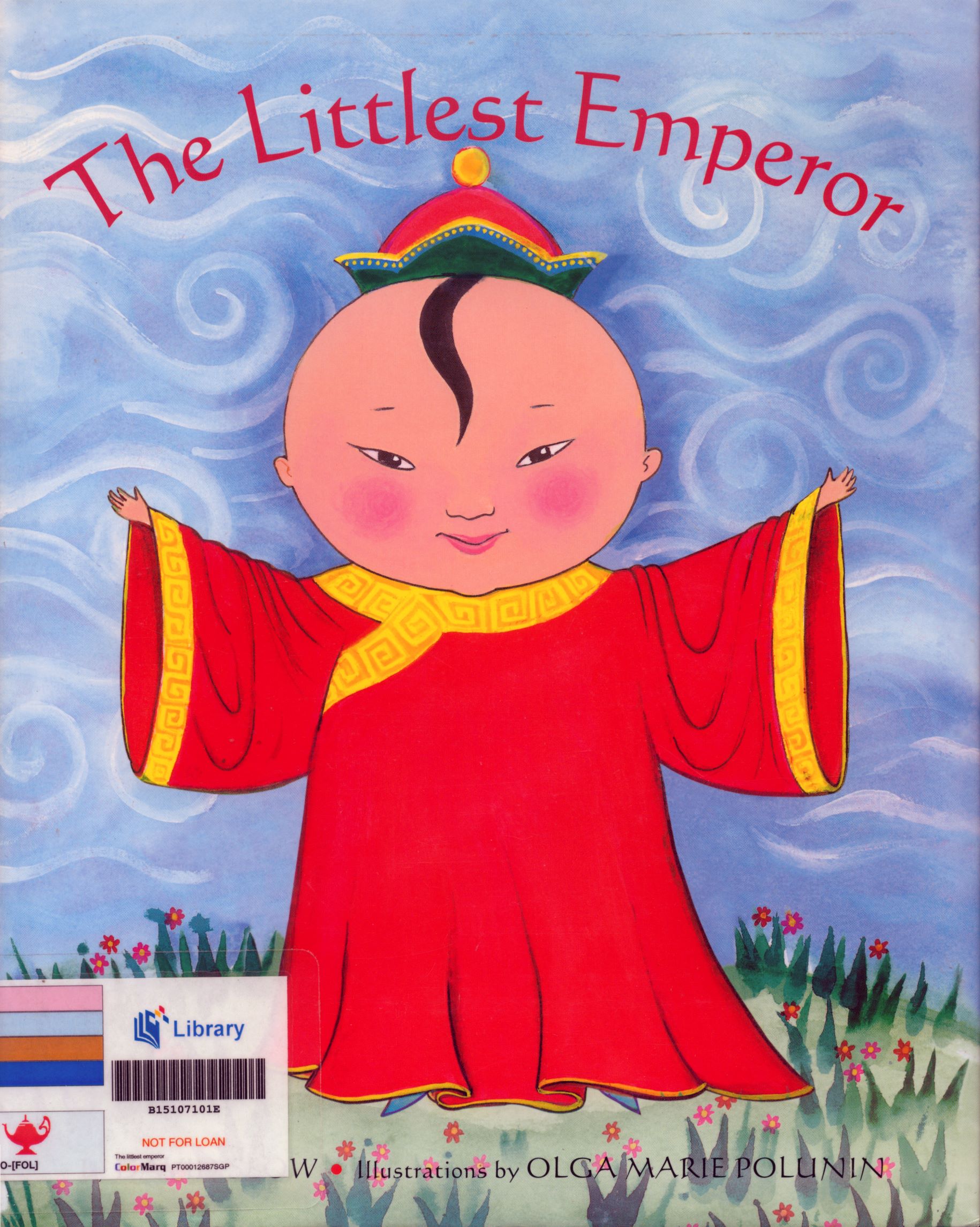

As we enter the new millennium (i.e., 2000s), better and more interesting books are published locally, such as Linda Gan’s A Treasury of Asian Folktales (2000), Chandran Dudley’s Tales from the Islands of Singapore (2001) and David Seow’s The Littlest Emperor (2004). However, a new challenge has emerged: there are now more distractions (e.g. online and video gaming, and movies on video) than before. Claire Chiang, chairperson of the Asian Festival of Children’s Content Advisory Board, highlighted a very real and challenging issue we are facing today: “Reading habits have decreased because of new social media platforms. We need relevant and interesting books to recapture the imagination of our children” (cited in Ng, 2010b, p. C6).

The author wishes to acknowledge the contributions of Dr Wong Meng Ee, Early Childhood and Special Needs Education, National Institute of Education, Singapore, in reviewing this article.

Lee Kong Chian Research Fellow (2010)

REFERENCES

Anuar, H. (1972, November). Workshop on children’s books, Singapore 11–13 October 1971. Singapore Book World, 3, 3–4. (Call no.: RSING 070.5095957 SBW)

Blair, A. (1982). The friendly Malcinds. Singapore: Longman Malaysia. (Call no.: RCLOS 823.01 BLA)

Blair, A. (1985). The little people of Malcindia. Singapore: Longman. (Call No.: RCLOS 823.01 BLA)

Butterworth, M. (1994). The book behind the terminal: Electronic tools help children find what they want in bookshops and libraries. Singapore Book World, 24, 5–10. (Call no.: RSING 070.5095957 SBW)

Cameron, J. (2009). Avatar: The Na’vi quest. New York, NY: HarperCollins.

Chandran, R. (1997). I have touched the moon! Singapore: NTUC Childcare Co-operative. (Call no. JRSING 428 SHA)

Chia, N.K.H. (1991). The imaginative creation of metalworlds in the recreational reading process. Education Today, 41 (3), 22–25.

Chia, N.K.H. (1993). Iron Pa Pa. Singapore: Cobee Publishing House. (Call no.: JR S823 CHI)

Chia, N.K.H. (1996, November/December). The Neverland of fantasy. Family Tree, 14. (Call no.: RCLOS q052 FT)

Chia, N.K.H. (2004). R=T(D+C)+M… and what else? SRL newsletter, 17 (3), 3–9. (Call no.: RSING 372.405 SRLN)

Dudley, C. (2001). Tales from the islands of Singapore. Singapore: Landmarks Books. (Call no.: RSING 398.2095957 CHI)

Ende, M. (1979). Die unendiiche geschichte [The neverending story]. Stuttgart, Germany: Thienemann Verlag.

Egan, K. (1992). Imagination in teaching and learning. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Gan, L. (2000). A treasury of Asian folktales. Singapore: Earlybird Books.

Girvin, M. (1976). Planning, production and distribution of children’s books: The Singapore situation. Singapore Book World, 7, 6–10. (Call no.: RSING 070.5095957 SBW)

Hassan, F. (2006, July). Beyond the readers and folktales: Observations about Singapore children’s literature. BiblioAsia, 2 (2), 16–19. Retrieved from BiblioAsia website.

Khoo, S.L. (1990/91). Children’s literature in English. Singapore Book World, 20, 20–25. (Call no.: RSING 070.5095957 SBW)

Khoo, S.L. (1992). A study of the problems inherent in attempting to define a literature for children. [n.p.]. (Call no.: RSING 809.89282 KHO)

Koh, B.S. (1994, July 4). Private sponsorship of libraries can spur the reading habit. The Straits Times, p. 4. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Kong, L., & Tay, L. (1998). Exalting the past: Nostalgia and the construction of heritage in children’s literature. Area, 30 (2), 133–143. Retrieved from JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website.

Leavis, F.R. (1950). Mill on Bentham and Coleridge. London, UK: Chatto.

Lee, T.P. (1990/91). Keynote address by Lee Tzu Pheng at the seminar: In search of a Singapore Children’s Literature, 6–7, September 1990. Singapore Book World, 20, 8–17. (Call no.: RSING 070.5095957 SBW)

Lim, P.H.L. (Ed.). (2009). Chronicle of Singapore: Fifty years of headline news 1959–2009. Singapore: Editions Didier Millet & National Library Board. (Call no.: RSING 959.5705 CHR)

Lynch-Brown, C., & Tomlinson, C.M. (2008). Essentials of children’s literature. Boston, MA: Pearson Education.

Media Development Authority. (2005, September 15). New publishing initiative for aspiring writers and illustrators. Retrieved from Infocomm Media Development Authority website. Ministry of Community Development. (1988). Report of the committee on literary arts. Singapore: Ministry of Community Development. (Call no.: RSING S820 SIN)

Nair, C. et al. (1977). Common elements in books children like; The Singapore experience. Singapore Book World, 8, 9–18. (Call no.: RSING 070.5095957 SBW)

National Book Development Council of Singapore. (1981). A guide to writing of children’s books: Proceedings of the writer’s workshop on children’s books (pp. 36–42). Singapore: Educational Publications Bureau. (Call no.: RSING 808.0683 WRI)

National Library Board. (2005). Singapore children’s literature: An annotated bibliography. Singapore: National Library Board. (Call no.: RSING 015.5957 SIN)

Ng, M. (2010, May 2). Writing bestsellers for kids. The Straits Times, p. 6. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Ng, M. (2010, March 1). J.K Rowling of our own? The Straits Times, p. 6. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Norman, R. (2000). Cultivating imagination [Unpublished paper presented at the Adult Education Proceedings of the 41st Annual Adult Education Research, Vancouver, Canada, June 2–4].

Riordan, R (2008). Percy jackson and the olympians, books i-iii [electronic resource], books 1–3. New York, NY; Hyperion Books for Children. Retrieved from OverDrive. (myLibrary ID is required to access this ebook)

Roloff, L.H. (1973). The perception and evocation of literature. Boston, MA: Scott & Foresman.

Roth, I. (2004). World of the mind: Imagination. Retrieved from answers.com website.

Seow, D. (2004). The littlest emperor. Boston, MA: Tuttle. (Call no.: JRSING 398.2 SEO)

Sewall, L. (1999, Autumn). Imagination: Creating a new reality. Orion, 17 (4).

Singh, K. (1993/94). Singapore fiction in English: Some reflections…”. Singapore Book World, 23, 21–23. (Call no.: RSING 070.5095957 SBW)

Sutton-Smith, B. (1988). In search of the imagination. In K. Egan & D. Nadaner (Eds.), Imagination and education (p. 22). New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

Tomlinson, C.M., & Lynch-Brown, C. (2010). Essentials of young adult literature. Boston, MA: Pearson Education.

Wee, J. (1990/91). The writer’s view. Presented during session 3: The creation and distribution of children’s literature, at the Seminar: In search of a Singapore Children’s Literature, September 6–7 September, 1990. Singapore Book World, 20, 38–40. (Call no.: RSING 070.5095957 SBW)

Wong, R. (1972, November). Speech by Dr Ruth Wongat the opening of the workshop on children’s books. Singapore Book World, 3, 5–6. (Call no.: RSING 070.5095957 SBW)

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Active readers series. (1970). Singapore: Federal Publications.

Akbar, A. (1961). Federal supplementary readers. Third year (Book3). Singapore: Federal Publications. (Available via PublicationSG)

Blair, A. (1982). The friendly Malcinds. Singapore: Longman Malaysia. (Call no.: RCLOS 823.01 BLA)

Blair, A. (1985). The little people of Malcindia. Singapore: Longman. (Call no.: RCLOS 823.01 BLA)

Chan, K.I. (1979). Ah Lee the road sweeper. Singapore: Education Publications Bureau. (Call no.: RCLOS 428.6 CHA)

Chia, H.C. (1974). The Redhill (Moongate Collection: Folktales from the Orient). Singapore: Federal-Alpha. (Available via PublicationSG)

Chia, H.C. (1975). The Raja’s crown: A Singapore folktale (Moongate Collection: Folktales from the Orient). Singapore: Federal-Alpha. (Available via PublicationSG)

Chia, M.A., & Chia, H.C. (1968). The king of fishes. Singapore: Donald Moore Press. (Call no.: RCLOS 428.6 CHI)

Courtesy is John’s way of life. (1979). Singapore: Seamaster Publishers. (Call no.: JRSING 428.6 SEA)

Federal readers. Book one. (1963). Singapore: Federal Publications. (Call no.: RCLOS 428.6 FED)

Ministry of Education. (1975). The Singapore Youth Festival. Singapore: Educational Publications Bureau. (Not available in NLB holdings)

Sherry, S. (1985). Street of the small night market. Singapore: Times Books International. (Call no.: RSING 823.914 SHE)

Tan, B.Y., & Chia, H.C. (1978). New way readers 1A. Singapore: Pan Pacific Book Distributors. (Available via PublicationSG)

Veloo, R. (1990). Kampung chicken. Singapore: Angsana Books. (Call no.: RSING S823 VEL)

Wee, J. (1980). The Adventures of Mooty the Mouse Series. Singapore: Federal Publications.

Wee, J. (1980). Mooty and grandma. Singapore: Federal Publications. (Available via PublicationSG)

Wee, J. (1980). Mooty and the satay-man. Singapore: Federal Publications. (Call no.: JRSING 428.6 WEE)

Wee, J. (1980). Mooty falls in love. Singapore: Federal Publications. (Call no.: JRSING 428.6 WEE)

Wee, J. (1980). Mooty goes to school. Singapore: Federal Publications. (Call no.: JRSING 428.6 WEE)

Wee, J. (1980). Mooty has a son. Singapore: Federal Publications. (Call no.: JRSING 428.6 WEE)

Wee, J. (1988). Mooty moves out. Singapore: Federal Publications. (Available via PublicationSG)

Wee, J. (1980). Mooty plays hide-and-seek. Singapore: Federal Publications. (Call no.: JRSING 428.6 WEE)

Wee, J. (1980). Mooty saves a life. Singapore: Federal Publications. (Call no.: JRSING 428.6 WEE)

Wee, J. (1980). Mooty the space-mouse. Singapore: Federal Publications. (Call no.: JRSING 428.6 WEE)

Wee, J. (1984). Boo! Singapore: Educational Publications Bureau. (Call no.: RCLOS S823 WEE)

NOTES

-

Literary processing channels, also known as fantasising (see Chia, 1991, 1996a), are unlike literacy processing channels which involve reading and writing processes. ↩

-

See http://www.answers.com/topic/imagination ↩

-

The term imaginativity is coined here to denote the ability to reproduce mental images as a result of apprehending the textual and/or non-textual experiences by means of the senses or of the mind, or to recombine previous experiences in producing new images directed at a specific goal or aiding in solving a problem. ↩