Drying Fish in Singapore Art: Making Sense of the Nanyang Style

The act of drying fish appears in many works of the Nanyang style. National Art Gallery’s Yeo Wei Wei explores this recurring motif and suggests how it can help our understanding of “Nanyang”.

“Nanyang”: Nostalgia and Longing

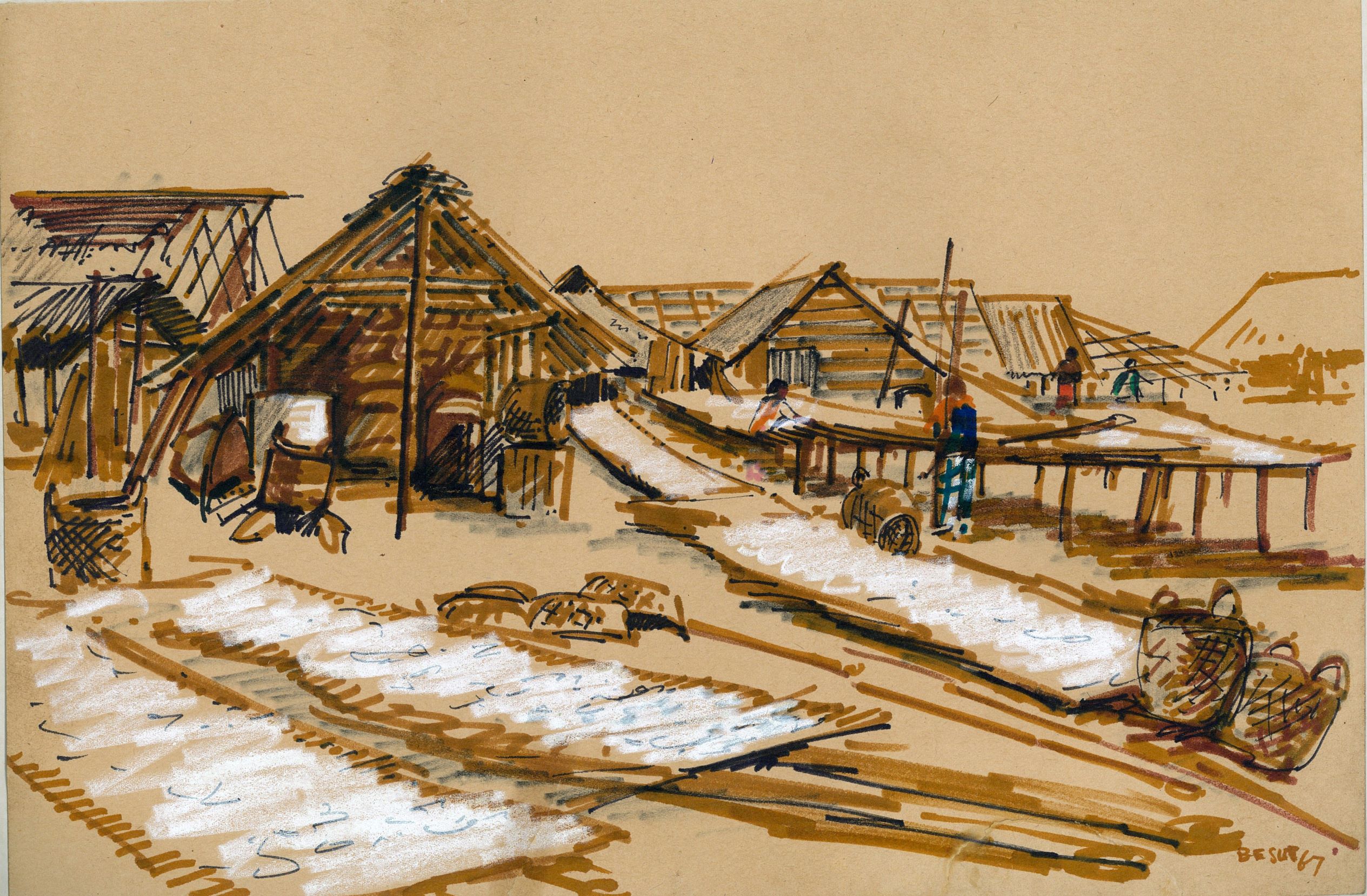

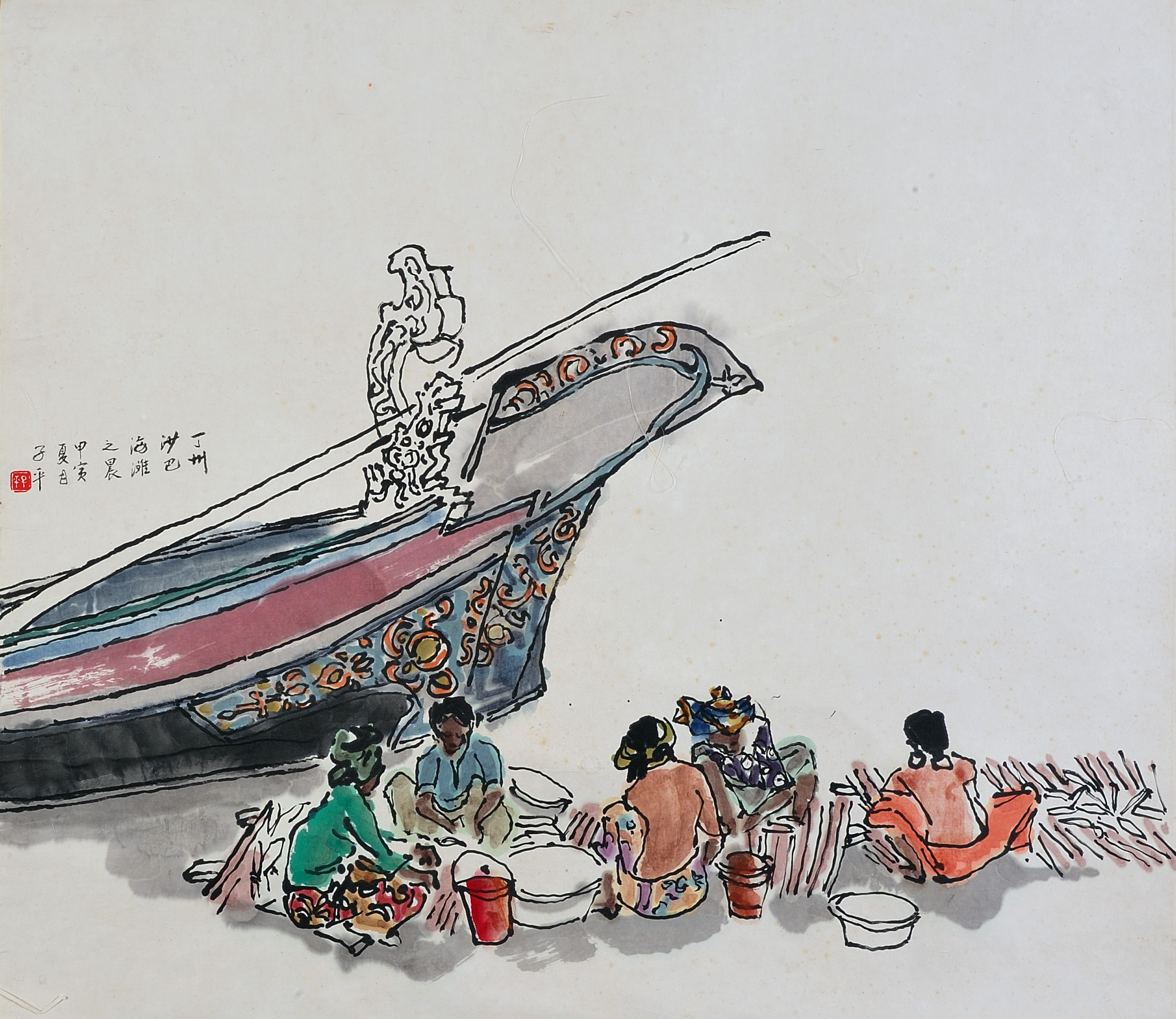

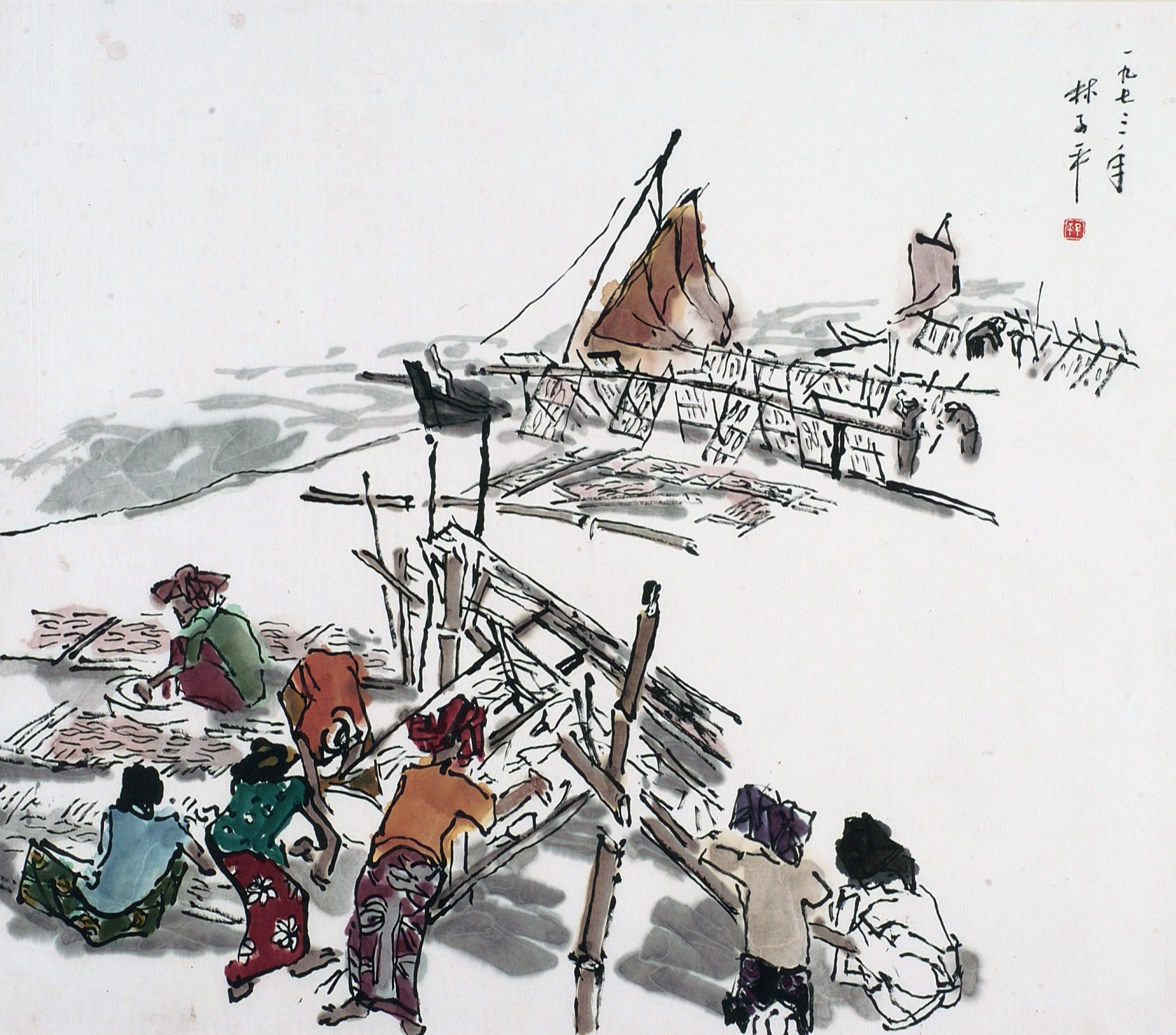

The subject of drying fish appears with remarkable frequency in the works of modern Singapore artists in the 1960s and 1970s. During that time, artists such as Chen Chong Swee, Cheong Soo Pieng, Lim Tze Peng and other members of the Ten Men Art Group, travelled to fishing villages in Terengganu, Kelantan and Kukup. These outdoor sketching trips and the works produced in their course form part of the evolution of the Nanyang style. Finding themselves surrounded by attractive and fresh subject matter, these artists spent their days fruitfully; many sketches were the basis for full-fledged works in oil, watercolour, Chinese ink and colour, and even wood carving.

“Nanyang” literally means “south seas”, yet the term’s significance goes beyond mere geographical denotation. From the time of the earliest huaqiao (华侨; emigrants who came largely from southern China), “Nanyang” served as a potent signifier for a certain projected way of life in the tropics, a more rewarding life with less hardship. It was a word loaded with hope and aspirations, but interestingly, by the early 1950s, it also seemed to evoke longing for an idyllic pastoral paradise in the tropics. The passion for tropical beauty had clearly grown since the 1920s. Back then, the writer Chen Lianqing lamented the absence of “local colour” in the literature of that time: “Look where you will in these magazines, you will find scarcely anything that conveys in any satisfactory way the colour of the South Seas” (Fang, 1977). It was the search for “local colour” that spurred the four major first-generation artists Cheong Soo Pieng, Chen Chong Swee, Chen Wen Hsi and Liu Kang to embark on their now-famous field trip to Bali in 1952. They stayed in Bali for more than three weeks, travelling extensively across the island. The works from that Bali trip became emblematic of the Nanyang style. The four artists were aware of Bali’s special place in the hearts of artists like Le Mayeur; Chen Chong Swee wrote about Le Mayeur’s exhibition in Singapore in 1938. The spotlight on Bali as a holy grail of sorts in the quest for the “Nanyang” in art, shifted to Malaysia in the 1960s. Bali was sought after, but it was also costly to travel there; second-generations artists who aspired towards the Nanyang style found it more economical to travel to Malaysia.

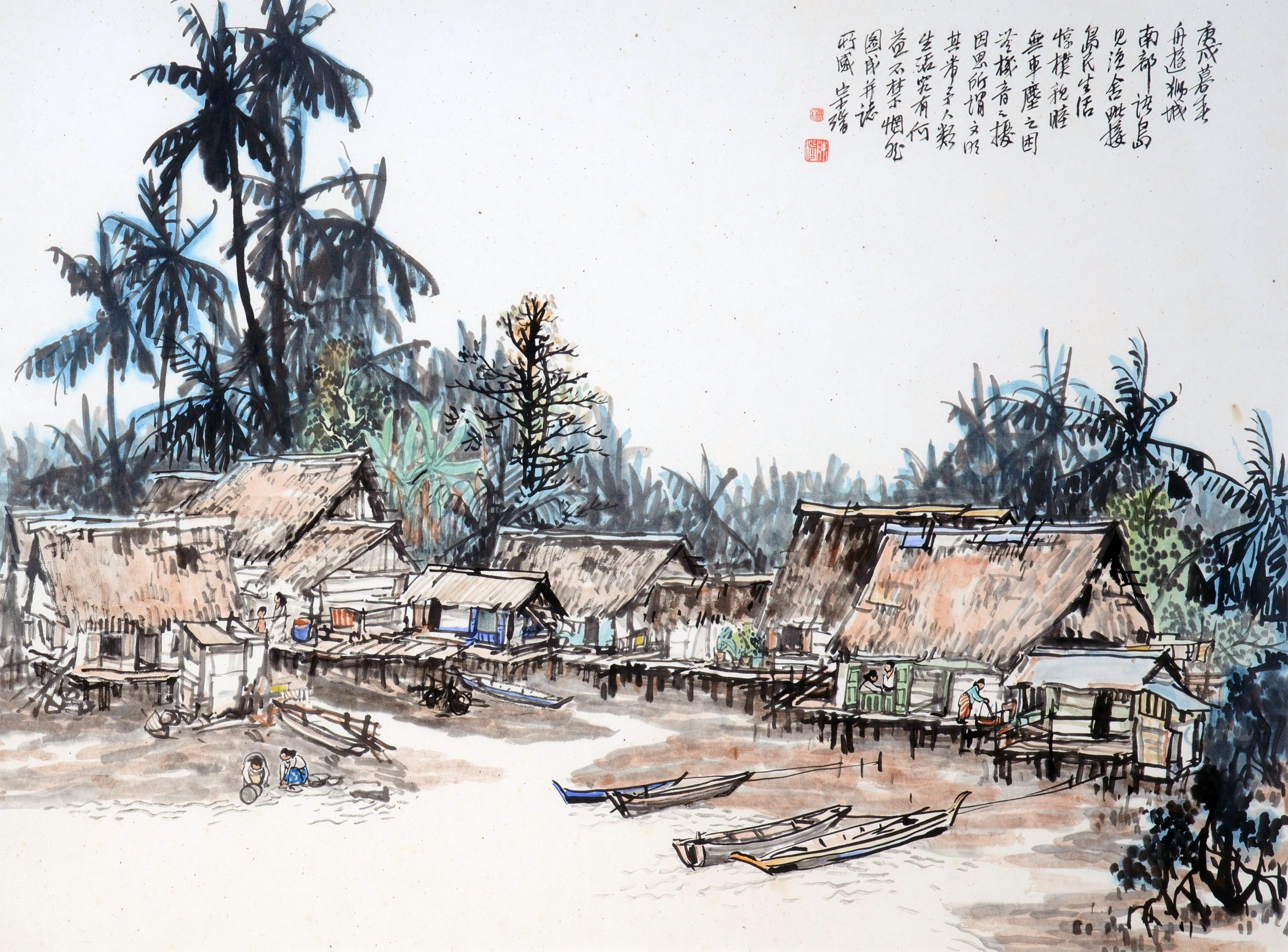

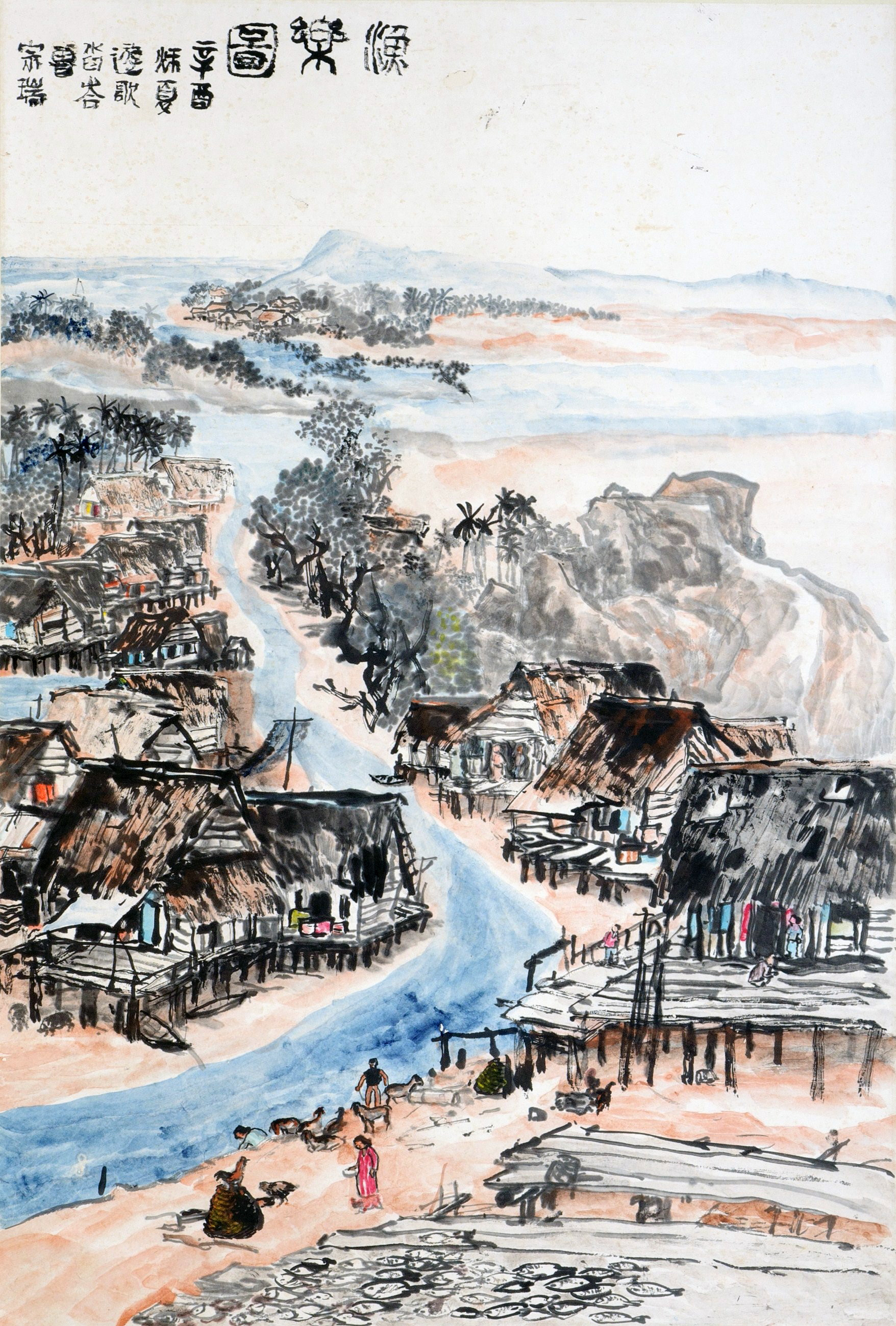

In a way, the “Nanyang” art of the 60s and 70s acts as a mirror, catching reflections of the responses by artists and the community to dramatic political changes on both sides of the strait. Singapore’s relationship with Malaysia was being dramatically reconfigured. In Singaporean artists’ representations of Malaysian fishing village life during that time, there is no shadow of separation; “Nanyang” continues to encompass the nations of Singapore and Malaysia, uniting them through nostalgia and new works of art. On their visits to fishing villages on the east coast of Malaysia and other nearby places in the 1960s and 1970s, the artists were attracted by sights that no longer existed in Singapore due to its rapid industrialisation. Chen Chong Swee had painted the fishing villages in the west coast of Singapore in the 1960s, for example, in Singapore West Coast (1962). However, the development of the west coast led to the disappearance of these scenes and the artist began to travel to the east coast of Malaysia, often accompanied by his students such as Tan Teo Kwang (personal communication in Mandarin with Chen Chi Sing, 21 January 2011). In the colophon of his painting, South Islanders (1970), Chen Chong Swee celebrates the peace and harmony of village life on the Southern Islands:

The fisher folk live in simple joy and harmony

No cars, no dust, no

noise

One might ask if civilisation

brings any good

The question

persists, and this picture was made

(Chen, 2010; trans. Yeo, 2011)

In another painting, Fishing Village (1981), the title in Chinese literally translates as “Happy Fishing Picture”; the first two characters “渔乐” (yule) have the same sound as the characters for recreation “娱乐”, a pun expressing Chen Chong Swee’s appreciation of the leisurely and relaxed pace of life in Kota Bahru. In the foreground, fishes are laid out to dry.

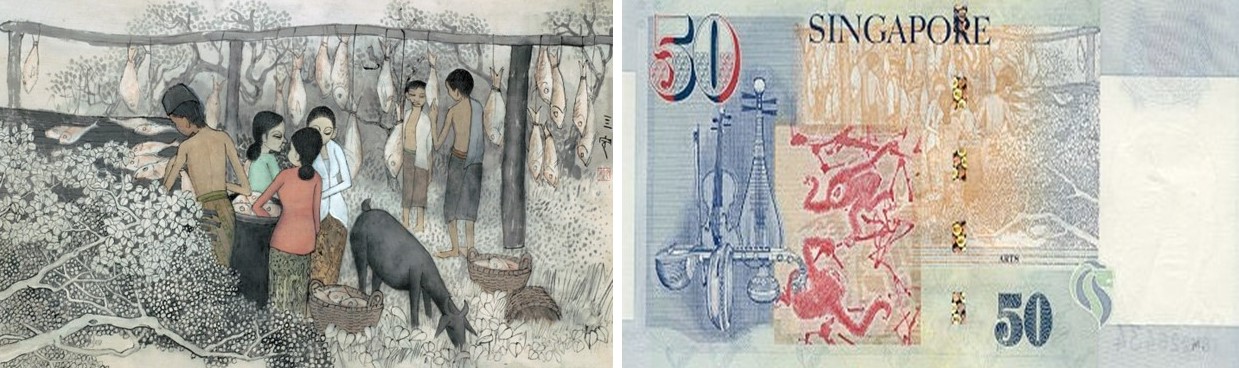

Born in the 1910s, 1920s and 1930s, these artists grew up knowing Singapore as part of Malaya. Scenes of drying fish were common in Malaysia, a familiar familial country, a place that was as homely as Singapore during the artists’ childhood. By the mid-80s, the appeal of the subject had begun to fade. However, the selection of Cheong Soo Pieng’s painting Drying Salted Fish (1978), featuring a scene from Terengganu, as part of the redesign of the Singapore fifty-dollar note in 1999 seemed to be a silent acknowledgement that Singapore had once been part of Malaya.

(Right) Singapore banknote in fifty-dollar denomination from the Portrait Series (reverse). Note inset of Cheong Soo Pieng’s Drying Salted Fish.

“Nanyang”: Phenomenology

The “south” (南, nan) in “Nanyang” refers to coordinates taken from the perspective of China. The term gestures towards an Elsewhere situated south from the mainland, serving as a catchall for a region made up of diverse cultures and communities. The artists who pursued the Nanyang style were not unaware of the cultural richness and diversity of their region. The genesis of the Nanyang style is seeded upon awareness and openness to difference: the different light in the tropics; the different colours of other races in their skin tones and dress; the different hues, forms, and textures of tropical plants and fruits. As first-generation artist Liu Kang put it:

(Liu, 1969; trans. Tan, 2011)

Even as the artists appreciated the simple pleasures of the villagers’ lives, they were acutely conscious of their differences from the fisher folk. Tay Boon Pin recalls that the villagers lived in huts without tiled flooring and that their meals were very basic (personal communication in Mandarin with Tay Boon Pin, 28 December 2010). The world of simple fishing folk, the tough conditions of their lives, scenes of physical labour – these landscapes retain their visibility in works by artists who were themselves employed in white-collar professions and lived in the urban city-state of Singapore.

Standing in front of the pictures set in fishing villages, the spectator is confronted by this other world that is deemed characteristically “Nanyang” despite its distance and disparity from the artists’ everyday life. “Nanyang” connotes an aesthetic sensibility and sensory impressions that are tied to the artists’ sense of a particular type of society and culture in the tropics. An openness to natural, cultural, and social environments that were at a remove from the alienation and pollution of modern city life – in other words, the embracing of another possible way of life in the tropics – underpinned the artists’ commitment to the Nanyang style. They opened not only their eyes, but also their hearts and minds to transporting the world of “Nanyang” into art.

The sense of sight is, of course, primary in the spectator’s encounter with a painting. Yet the artist’s encounter with his or her subject cannot be exclusively visual: there are also the other senses, shaping and informing the artist’s experience. Of course there was a fundamentally visual impact in many key aspects of the environment found in the Malaysian fishing villages. The artists were enthralled by the striking design and structure of the fishing boats. Another popular subject was that of the fishermen mending or drying their nets. The wooden kelong structures on which fishermen and their families lived as well as worked lent themselves to renderings of “beautiful lines” (personal communication with Lim Tze Peng in Mandarin, 5 January 2011).

When the artists travelled out of Singapore, they went in search of new inspiration, for fresh air, as it were. As Chen Cheng Mei (also known as Tan Seah Boey) put it, “We were looking for new subject matter… artists have to see the world and learn from the world” (personal communication with Chen Cheng Mei, 21 January 2011). The artists paid attention to every aspect of village life by the sea, spending days and nights in this environment; this is recounted in interviews and also evident from their sketches. Yet it has to be said that the attraction of the drying fish subject is curious: not only were the artists not deterred by the terrible odour emanating from the fish, they were also not put off by the negative association – in idiomatic Cantonese – of salted fish with death and misfortune. While the artists can be said to have responded with enthusiasm to the pictorial opportunities availed by the spectacle of many fish hung up or laid on the ground, the etymology of inspiration as something that is breathed in (from the Latin spirare) also comes into play. The drying of salted fish provided the artists with an intense olfactory experience.

It was not a pleasant smell. Lim Tze Peng remembers the unbearable odour emanating from the huts used for the cleaning of the fish:

(personal communication in Mandarin with Lim Tze Peng, 5 January 2011)

Yeh Chi Wei wrote about the nauseating odour of drying salted fish that permeated the air during the Ten Men Group’s first sketching trip to the east coast of Malaya in 1961. The artists spent their days sketching outdoors in the fishing villages, undeterred by the relentless heat and glare of the sun, and the stench:

(Yeh, 1961; trans. Yeo, 2010a)

Tay Boon Pin recounts that before the fish were dried, they had to be cleaned, their heads and organs removed. The fish would then be soaked in salted water for a few days before they were hung or laid out for drying under the sun. Apart from the stench, there were many flies buzzing around the fish (personal communication in Mandarin with Tay Boon Pin, 28 December 2010).

The point that is being made here is not that an awful, nauseating odour inspired all these works. Rather, there is an implicit reminder of the nature of transport that art-making affords and entails; a transcending of harsh or uncomfortable conditions in which the artists worked. As Thomas Yeo put it, “The appeal is not the smell. Your brain is not thinking of the smell. Your brain is concentrating on the subject matter. That is the priority” (personal communication with Thomas Yeo, 23 January 2011).

To transcend the physical conditions of art-making is not to detach oneself from the object, but to be immersed deeply within it and to thus express what is “seen” from that position. For Lim Tze Peng, the representation of smell can be an indication of an artist’s deep understanding of his or her subject – phenomenological understanding. Lim praised the still-life paintings of Georgette Chen, Singapore’s most renowned first-generation woman artist, in these terms; he also drew a parallel with his own paintings of salted fish:

Speaking of Cezanne’s achievement in his still-life paintings of apples, Lim referred to the French artist’s ability to render smell through these works:

“Nanyang”: Mythologies

Nostalgia and phenomenological fullness have been explored above as layers of significance in the Nanyang style. Yet the common ground yielded not a single result but much variety. The monolithic univocality of the “Nanyang Style” is specious; it is more appropriate to speak of Nanyang styles. Surveying the drying fish works reveals the singularity of each artist’s approach towards a shared subject matter. Cheong Soo Pieng’s Drying Salted Fish (1978) reflects the influence of Song-dynasty painting on the artist in his later years; the foliage in the foreground bears a striking resemblance to the Song painter Ma Hezhi’s depiction of leaves (Yeo, 2010b). With their elongated arms and rounded eyebrows, the female figures are also characteristic of Cheong’s decorative phase in the late 70s and early 80s.

These works by Chen Chong Swee and Shui Tit Sing were the result of a group trip to Terengganu in 1961. Their distinct ways of handling the same subject resulted in distinctive artworks. There are two different representations of time or chronology in these two works. In Shui Tit Sing’s oil painting, four different stages of preparing salted fish are assembled in the four sections. The figures are flat, rendered in a naive manner; coupled with the use of colours in the painting, it bears a resemblance to folk art. Life passes in repeated cycles, represented by the clockwise sequence of tableaux – the fishermen return, the women clean the fish, the fish are laid out or hung to dry; there is nothing new under the sun. The Chen Chong Swee watercolour, on the other hand, is a representation of an impression, of a scene of communal labour witnessed with sympathy and portrayed as such. Although the features of their faces are not clear, the figures are not depicted as anonymous or homogeneous; each bent back is laden with the weight of each person’s individual consciousness, personal hopes and worries, and memories both happy and sad. Time passes in daily routines, mundane activities and chores, yet it passes differently for each of us, in the minutiae of inner thoughts and feelings, in the vagaries and vicissitudes of every individual life. Chen’s works carry this signature sense of storytelling, of narratives coursing through a scene; his is a way of seeing that delves beyond observations of surface scenic attractions to suggest the pulse and eventfulness of life.

A shared nostalgia, a shared longing, the phenomenological experience of life and art, the individual artistic will and vision: all these layers of the Nanyang style come together in Seah Kim Joo’s Malayan Life (1968). Almost seven metres long and over two and a half metres tall, the entire work consists of five panels of batik painting, offering a visual feast of aspects of the “Nanyang”. The title is poignant. The sun had already set for Malaya, an obsolete referent in 1968 when this work was made. The dominant hue in the backdrop is a warm orange, like the light of a setting sun at dusk. It gestures, perhaps, to an analogy: the ending of a day with the ending of an era.

The phenomenological fullness of experience that is captured in art is also exemplified by the images Seah has depicted, images that relate the ways in which life captivates through much more than the sense of sight. Smell, touch, hearing – all these are evoked. The scene of drying fish stretches across the background of three of the five panels, making it probably the largest rendering of the subject around. On the second and third panels, villagers with upturned faces toward the hanging fishes seem to be inhaling deeply; three of them reach out their hands to hold or touch the fish. It is also curious that the artist includes the durian in the work, a fruit known for its overwhelming fragrance or pungent odour, the perception of which is dependent on one’s preference. In the bottom-right corner of the second panel, a small Malay boy has his head bent over a durian held between his palms, with an expression that resembles that of durian sellers who hold the fruit in exactly this manner and smell it to see if it is ripe.

The work is a phantasmagorical amalgamation of various aspects of life in different parts of rural Malaysia. Dayaks, an indigenous people from Borneo, are represented on the fourth and fifth panels in a riverside setting. One of them plays a musical instrument while the others stalk prey with their hunting implements at the ready. Birds are found on every panel: fluttering pigeons, flying canards, egrets, a rooster, an owl. Other animals include an ox and deer. The effect is of enchantment: recognisable ordinary features of the simple rural life are transformed into jigsaw pieces that fit together in a magical narrative, a picture of humankind and nature in harmony, the teeming tuneful life when all senses are awakened, unjaded. Everything is connected, even as they maintain their distinct form and function. Culture and nature are merged. The lines on which the fish are hung extend from the fishing net lines, but they are also the lines of string that bind flying birds to villagers; they are also the lines of string that make the solitary wayang kulit figure on the first panel dance.

Studying the representations of drying fish leads to a reexamination of the Nanyang style, to a reminder of the difference among its many proponents as well as their shared values and concerns. The mythologies of “Nanyang” that emerge from these artworks have become historical: the works themselves are a chronicle of a past time and past sentiments. As a chapter in Singapore art history, they demonstrate the surprise element that is characteristic of creativity, when something new is born out of the known. Who would have imagined that the scene of drying fish in humble fishing villages, the making of salted fish, a common and humble foodstuff, could be a source of inspiration for so many artists? Sometimes, art does not require the sublime for its subject, nor are its expressions confined to the lofty. The artworks have outlasted, and continue to outlive, the fish they portray.

The writer wishes to thank Chen Cheng Mei, Chen Chi Sing, Tan Wee Lee, Cheong Leng Guat, Huang Kaiquan, Koh Nguang How, LASALLE College of the Arts, Bryan Law, Lim Tze Peng, Charmaine Oon, Sara Siew, Tay Boon Pin, Rofan Teo, Xu Qingzhao, Wang Zineng and Thomas Yeo, for their assistance.

Assistant Director

Publications And Resource Centre

National Art Gallery, Singapore

REFERENCES

Chen, W., Chen, Q. & Qihua, Z. Yuancheng & Huang, J. (Eds.). (2010). Huashishicao – Chenzongruitihuashi. Singapore: Chen Chi Sing.

Fang, X., & Kazuo, E. (Eds.). (1977). Notes on the history of Malayan Chinese new literature, 1920–1942. Tokyo: Centre for East Asian Cultural Studies. (Call no.: RSEA 895.1 FAN)

Liu, K. (2011). Eastern and Western Cultures and Art in Singapore. In S. Siew (Ed.), T. T. Tan (Trans.), Liu Kang: Essays on art and culture (pp. 111—20). Singapore: National Art Gallery. (Original work published in 1981). (Call no.: RSING 709.50904 LIU)

Yeh, C.W. (1961). Preface. Shirenhuaji. Singapore.

Yeo, W.W. (Ed.). (2010). The story of Yeh Chi Wei. Singapore: National Art Gallery. (Call no.: RSING 759.95957 STO)

Yeo, W.W. (Ed.). (2010). Cheong Soo Pieng: Visions of Southeast Asia. Singapore: National Art Gallery. (Call no.: RSING 759.95957 SOO)