Women’s Perspectives on Malaya: Emily Innes on the Malay States

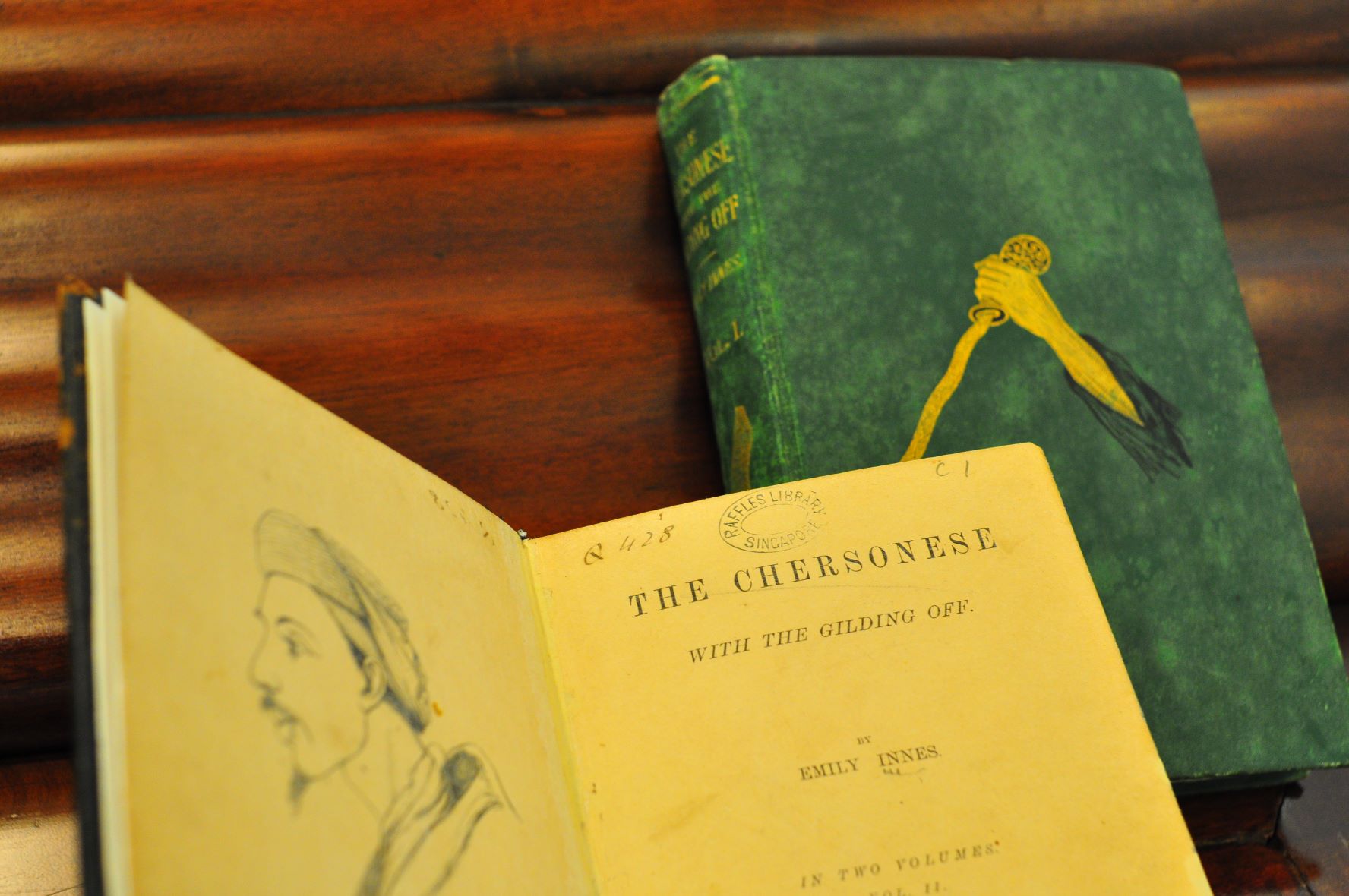

Senior Librarian Bonny Tan spotlights Emily Innes’ The Chersonese with the Gilding Off (1883), a work that stands apart from those of her female compatriots because she wrote as the wife of a minor British official at a time when few colonial wives had their insights published.

Emily Innes: Depicting the Chersonese

By the late 19th century, travelogues, surveys and government studies had covered much of Southeast Asia but most of these publications were written by men. The only women writers published were famed travel writers like Isabella Bird or wives of missionaries like Harriette McDougall. Emily Innes’ publication, The Chersonese with the Gilding Off (1883), thus stands apart from the work of her female compatriots because she wrote as the wife of a minor British official at a time when few colonial wives had their insights published.

James Innes was appointed Collector and Magistrate at Kuala Langat in Selangor in 1877. He had previously served in Sarawak and quickly risen to become Treasurer. Research showed that he had, unfortunately, faced problems with money throughout his career.1 James also proved impractical,2 shortsighted3 and unable to relate with his superiors.4 In a way, Emily’s book was written as a defence for her husband who had resigned his post after six years; his conflict with the Resident, Captain Bloomfield Douglas, being the main reason, though Emily’s stated reason is James’ opposition to slavery in the Malay States.

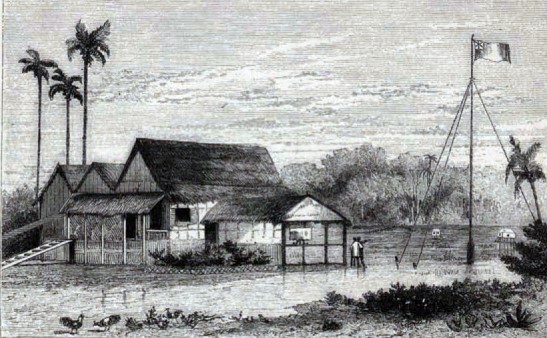

The two-volume work however depicts more than the Inneses’ dissatisfaction with the greater government and their acrimonious relationship with the Douglases. Tin mining production in Perak and Selangor had risen spectacularly in the 1870s, with the introduction of innovative tin mining methods adapted from Chinese rice planting irrigation techniques.5 In fact, the lucrative tin mining business saw Chinese immigrants increasing by large numbers in the Malay States.6 The explosive mix of wealth, new immigrants and old Malay rulers led to wars and conflicts. The British mediated at the invitation of local rulers, profiting at the same time – a period known as the British intervention. As the Inneses had resided at the Protected Malay States just after British intervention in 1874, Emily’s book gives a contemporaneous and vivid account from the unique perspective of the first British woman living in the interiors of the Peninsula. Self-taught in Malay, Emily’s descriptions of the Malay rulers, their villages and villagers as well as their initial reaction to British presence during intervention have proved valuable to historians studying this period (Gullick, 1993, p. 170).

Her publication is also interesting for its obvious play against the more famous work of Isabella Bird’s, The Golden Chersonese (1883).7 Giving the perspective of a resident instead of an acclaimed traveller, Innes wrote her piece “in contradistinction [to Bird’s] but with no aim of contradiction” (Doran, 2008, p. 175). Bird’s account of the Malay States was of five weeks between January and February 1879, while Emily’s is of her five-year residency from 1876 until her husband’s resignation in 1882.

Emily herself acknowledges the value and yet contrasting realities both authors portray in their writings:

.jpg)

Indeed, where Isabella visited the Malay States under the protection and support of government officials, “Emily Innes was… forced to endure – although with great bravado – the drudgery of swampy, lugubrious isolation, rickety atap-houses, a cretinous native society, deceitful servants and scarce food supply – not to mention a traumatic, near-fatal experience involving revolting Chinese coolies” (Wong, 1999).

Surviving the Chersonese

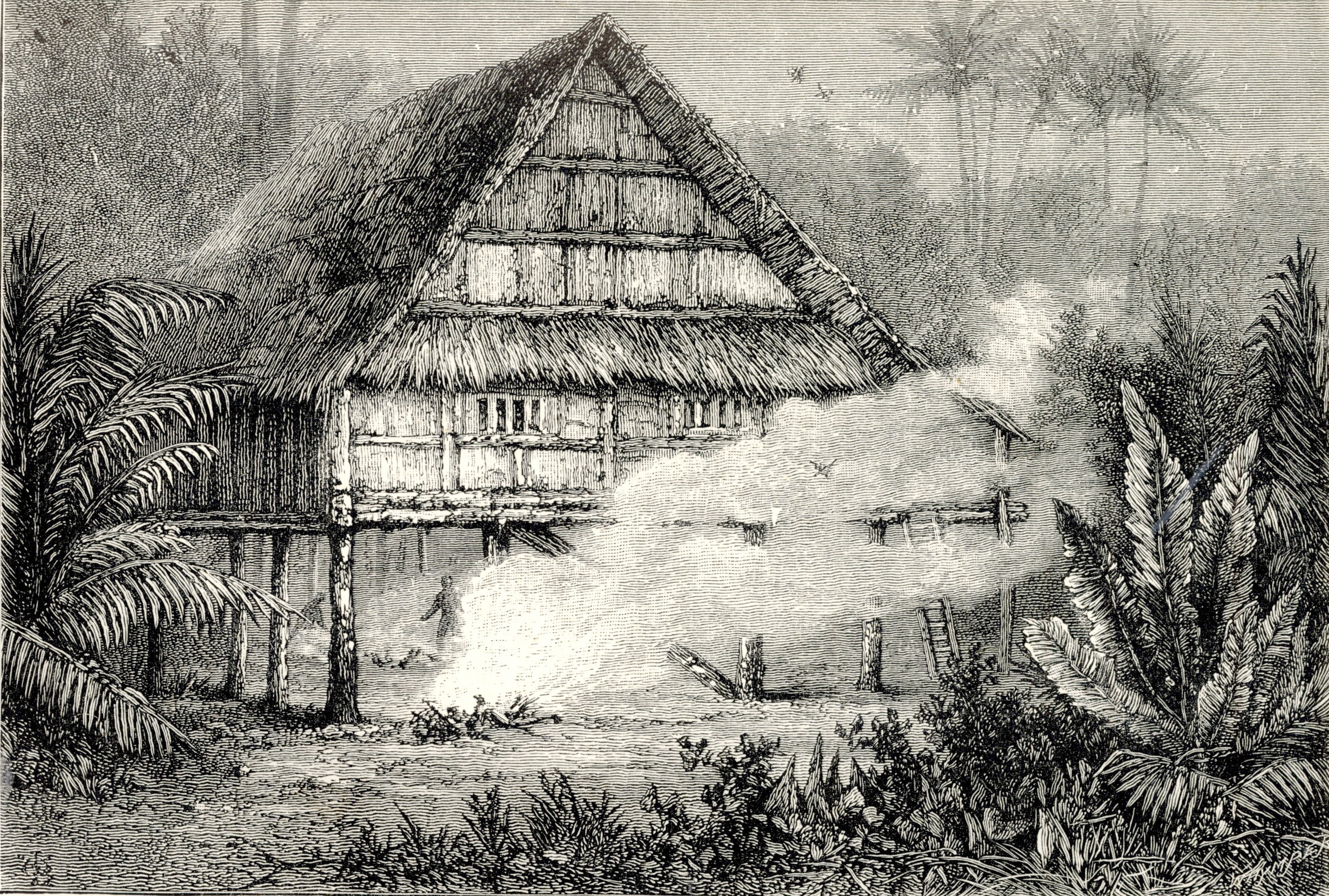

Volume 1 describes the Inneses at Langat,8 their first lodgings and experiences in the Protected Malay States while Volume 2 is of their stay at Durian Sabatang. Neither posting was comfortable, with the latter worse than the former. So depressing were their circumstances that, having just arrived at their “Malay wigwam” in Langat and taken a short walk to survey their surroundings in what little civilisation there was, they “agreed aloud that if [they] had to remain six months in this fearful place [they] must either leave the service or commit suicide” (Innes, p. 19). However, the Inneses survived not just six months but six years in the Malay States.

Though some have said Emily’s writings reflect “the mark of acute paranoia” (Heussler, 1981, p. 67), one must consider her dire circumstances. There was no ladies’ club or any other foreign women to commiserate with – only the intrusive locals and the overbearing sounds and sights of village life. Without children and at times, even a husband at home to occupy her, boredom was her constant companion.

.jpg)

Though her life was painfully boring, she wrote of her experiences and encounters with the wry sense of humour peculiar to the British:

For the well-read Emily, the only recourse to fighting the boredom was turning to books, but unfortunately her attempts at obtaining reading materials were unsuccessful:

Unable to escape into some form of leisure, Emily turned to studying the local habits and dispassionately describing her own struggles.

Much of Volume 1 thus documents mundane activities such as her attempts at cooking a decent meal with limited and poor-quality resources, the native behaviour of her Malay neighbours and the level of hygiene in the village or rather the lack of it. This volume also provides details about James Innes’ work and relationships with the locals and his colleagues, along with insights on personalities such as Bloomfield Douglas, Resident of Selangor, and Tunku Dia Udin, the Viceroy of Selangor – a critical character in the history of modern Selangor. The characters are rendered from a biased perspective because of the relationship she had with each of these personalities. Even so, they present unique angles for researchers, particularly as she wrote these descriptions from the perspective of a woman, and that of a wife of a British official.

Volume 2 describes the Inneses’ reluctant transfer to Durian Sabatang, the “white man’s grave”9 (Innes, p. 55), just as their more comfortable bungalow, designed by James Innes himself, was completed at Langat. A large part is devoted to an account of the tragic murder of Captain Lloyd, Superintendent of Dindings, at Pangkor and to the injuries sustained by Emily during the attack. Being new to the district and facing some discomfort, Emily had been invited to the Lloyds’ home: “I had never seen either of them, but that was of no consequence in a country where English are so rare that all are to a certain extent brothers” (Vol. 2, p. 91). In fact, the day Emily arrived, the Lloyds’ servants had not yet returned since receiving their pay and Mrs Lloyd, with three young children on hand, was in a quandary. The Lloyds’ troubles were only just beginning, as unemployed Chinese labourers in nearby Lumut saw the isolated Lloyds as a vulnerable and attractive target for a robbery. Unfortunately, Emily was a guest of the Lloyds on that fateful day such occurred. Mrs Lloyd and Emily were seriously injured in the attack on the family home but both survived the assault.

The tragedy saw Emily return on home leave, followed soon after by James who had become ill due to the conditions at Durian Sabatang. Although James returned to Bandar, he resigned within two years because of continued poor relations with the Resident. James’ departure from his position in the Malay States and the resultant loss of his much desired pension gave Emily the impetus to write this explanatory autobiography commenting on the injustices the Inneses had suffered under the poor leadership of their British compatriots.10

The author wishes to acknowledge the contributions of Dr Ernest C.T. Chew, Visiting Professorial Fellow, Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, in reviewing this article.

Senior Librarian

Lee Kong Chian Reference Library

National Library

REFERENCES

Anson, A.E.H. (1878, December 12). Topics of the day. The Straits Times Overland Journal, p. 2. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Bird, I.L. (1883). The golden Chersonese and the way thither. London: John Murray. (Call no.: RCLOS 959.5 BIS)

Bird, I., & Chubbuck, K. (Ed.). (2002). Letters to Henrietta. London: John Murray.

Chew, E.C.T. (1966). Sir Frank Swettenham’s Malayan career up to 1896. Singapore: University of Singapore Library.

Doran, C. (2008). Golden marvels and gilded monsters: Two women’s accounts of colonial Malaya. Asian Studies Review, 22 (2), 175–192.

Gullick, J.M. (1993). Emily Innes 1876–1882. In Glimpses of Selangor, 1860–1898 (pp. 157–192). Kuala Lumpur: Malaysian Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society. (Call no.: RSING 959.5104 GUL)

Gullick, J.M. (Ed.). (1995). Emily Innes: Keeping up one’s standards in Malaya. In Adventurous women in South-east Asia – six lives (pp. 147–195). Kuala Lumpur: Oxford University Press. (Call no.: RSING 959 ADV)

Heussler, R. (1981). British rule in Malaya: The Malayan Civil Service and its predecessors 1887–1942. Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press. (Call no.: RCLOS 354.5951006 HEU)

Innes, E. (1885). The Chersonese with the gilding off. (2 vols.). London: Richard Bentley & Sons. (Call no.: RRARE 959.51033 IN; Microfilm nos.: NL26023, NL7462)

Innes, E. (1974). The Chersonese with the gilding off: With an introduction by Khoo Kay Kim. Kuala Lumpur: Oxford University Press. (Call no.: RCLOS 959.5 INN)

Innes, E. (1993). The Chersonese with the gilding off. (2 vols.). Kuala Lumpur: Oxford University Press. (Call no.: RSING 915.951043 INN)

Jedamski, D. (1995). Images, self-images and the perception of the other women travellers in the Malay Archipelago. Hull, England: University of Hull, Centre for South-East Asian Studies. (Call no.: RSING 155.33309598 JED)

Knowles, M.I. (1935). The expansion of British influence in the Malay Peninsula, 1867–1885: A study in nineteenth century imperialism. Madison: University of Wisconsin. (Call no.: RSING q959.51033 KNO)

Port Klang Integrated Coastal Management Project. (2004). Background: Klang District-General. Retrieved from Port Klang ICM Project Management Office website.

Sadka, E. (1968). The protected Malay States, 1874–1895. Kuala Lumpur: University of Malaya Press. (Call no.: RSING 959.51034 SAD)

Sutton, H.T. (1959, March 7). The Lumut tragedy. The Straits Times, p. 9. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Tay, E. (2008). Discourses of difference: The Malaya of Isabella Bird, Emily Innes and Florence Caddy. In S. Clark and P. Smethurst, Asian crossings: Travel writing on China, Japan and Southeast Asia. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press. (Call no.: RSEA 915 ASI)

Wong, Y.S. (1999, May). Bibliography: 19th century AD. The Canadian Review of Sociology and Anthropology.

NOTES

-

Gullick details some of James Innes’ inadequacies in managing finances, a characteristic which likely led to problems with his superiors particularly in his role as Treasurer and Collector. (Gullick, 1993, pp. 162–164, 167–169) ↩

-

For example, Emily was made to trudge through the wilderness at her husband’s whim, a supposedly short few miles to the main town. However, her flouncy and uncomfortable English dress, the muddy conditions, the failing light of twilight and James’ forgetting his way meant the party was soon lost in the dark and Emily left in great discomfort. ↩

-

James resigned his post in Malaya only to regret this much later as he forfeited a pension subsequently linked to his position. ↩

-

Although initially the Inneses seemed to get along with the Resident at Selangor, Bloomfield Douglas, relations quickly deteriorated. ↩

-

The women had never met but Isabella was escorted through Selangor by James. Isabella notes that James was in “dejected spirits, as if the swamps of Durian Sabatang had been too much for him” (Bird, 1883, p. 276) though in her private letters, Isabella mentions that she found James “a main with a feeble, despairing manner and vague unfocussed eyes… a very dreary and unintelligent companion”. (Bird & Chubbuck, 2002, p. 273). ↩

-

Today, the district is known as Kuala Langat. The Klang Wars of 1868 saw the royal town move from the ancient centre of Jugra to Bandar Temasya and the town became key to the development of Selangor during the reign of Sultan Abdul Samad Ibn Almarhum Raja Abdullah (Port Klang Integrated Coastal Management Project). ↩

-

A name given for the “unhealthiness of its climate”. (Innes, 1885, p. 55) ↩

-

A note from this article’s reviewer, Ernest Chew: “Captain Bloomfield Douglas was succeeded as British Resident of Selangor by the youthful and more efficient Frank Swettenham, who subsequently became Resident of Perak, Resident-General of the four Federated Malay States, and finally Governor of the Straits Settlements and High Commissioner for the Malay States.” ↩