Negotiating the Cultural and the Religious: The Recasting of the Chinese Indonesian Buddhist

Lee Kong Chian Research Fellow Setefanus Suprajitno investigates the predicament faced by Buddhism in Indonesia through studying the Chinese Indonesian Buddhist community in Surabaya.

Travelling down Jalan Darmo – the arterial road through downtown Surabaya – you will pass by a mosque. It is not very big, but its identity can be instantly discerned from its facade. Further north, near the junction between Jalan Darmo and Jalan Polisi Istimewa, you will see a building that resembles a church. A few minutes’ journey later, you will come across the Buddhist temple, or vihara. The temple will appear to be like an ordinary building. A former shophouse, it has since been converted to a vihara. There are no outer signs that it is a vihara except for the small stupas1 on the two pillars in the sidewalls. The three places of worship above illustrate the situation Buddhism faces in Indonesia.

With the exception of some Buddhist temples – especially those with a large number of non-Chinese devotees – and old Chinese temples, most Buddhist temples are originally commercial buildings or houses converted into temples. For this reason, they usually do not resemble Buddhist temples from their exteriors. The indicators that they are Buddhist temples are usually small Buddhist icons, such as stupas. Even then, there are temples that display no outer sign that they are Buddhist temples, except in their name. People may conclude that these structures present a low-profile image. However, the extent of this low-profile may be some indication of the challenges that Buddhism – a state-sanctioned religion – faces, despite the Indonesian constitutional guarantee of freedom of religion.

My investigation of the Chinese Indonesian Buddhist community in Surabaya shows the predicament that Buddhism faces in Indonesia. In this article, I shall examine these problems.

Historical Entanglements

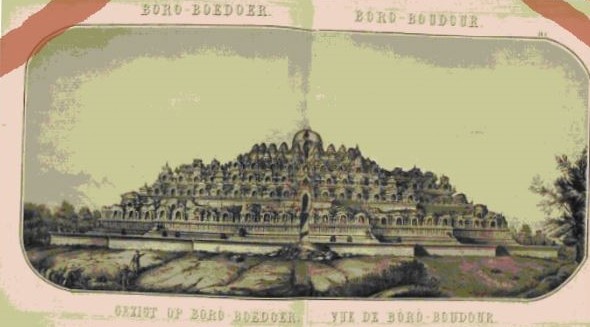

Historical records show that Buddhism has been in Indonesia for centuries. A well-known Chinese monk, Fa Xian (also known as Fa-hien) visited Java during his journey back to China after acquiring Buddhist texts from India in 399–414 CE. He observed that there were a number of Buddhists on the island (1984, p. 113). Yi Jing (I-tsing), a Chinese monk of the Tang-dynasty era who travelled to India in 671–695 CE, noted that Sriwijaya, an ancient kingdom in Sumatra, had become the centre of learning in the Buddhist world (2007, pp. 183–184). Buddhism also spread to the neighbouring island of Java during the golden age of the Sailendra dynasty (750–850 CE). The monumental Borobudur temple that was built in around 800 CE by the Sailendra kings is a testament to the growth of Buddhism in Java. The site is also listed in the World Heritage List of the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO).

However, the fall of the last Hindu-Buddhist kingdom in the 15th century and the spread of Islam changed the religious landscape in the archipelago and ushered in the demise of Buddhism (Barnes, 1995, p. 171). Nevertheless, Buddhist influence still remains, at least in the Javanese people’s worldview and in the form of their traditional beliefs and rituals such as meditation, known as kejawen (Javanese mysticism). Anthropologist Niels Mulder writes that many aspects of Javanese mysticism inform Javanese “ethics, customs, and style” and “are generally thought to hark back to the Hindu-Buddhist period of Javanese history” (2005, p. 16). Another scholar, Robert W. Hefner, states that Hindu-Buddhist traditions still survive in Islamised Java (1983, p. 666). With these deep roots into society, how can Buddhism still face problems in modern Indonesia? The answer lies in the history of the reappearance of Buddhism.

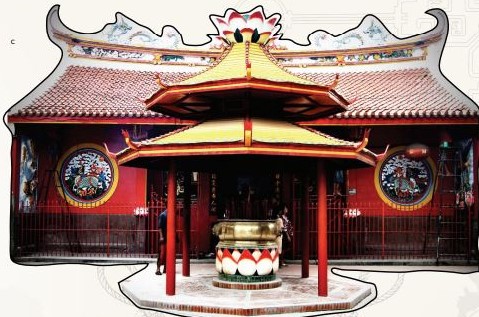

Buddhism started to resurface in the 17th century, although it was mixed with Daoism and Confucianism, thanks to the influx of Chinese immigrants in Indonesia. They brought their beliefs and established places of worship. The first Chinese Buddhist temple – Jin De Yuan (also known today as Dharma Bhakti vihara) – was built in 1650 in the Glodok area of Jakarta (Salmon, 2003, p. 18). Since then, Buddhism has grown in tandem with the Chinese community in Indonesia – mixed with Chinese traditional beliefs. In order to cater to the spiritual needs of the Chinese, more Chinese Buddhist temples were built.

The arrival of Dutch theosophists in colonial Indonesia in the late 19th century contributed to the revival of interest in Buddhism. They created The Theosophical Society, an avenue for exploring the esoteric eastern mysticism. This society became so popular that in a short time it attracted many new members from a variety of ethnic groups like the Dutch, the Chinese and local native elites (Nugraha, 1995, p. 19, 23). The popularity of the theosophical movement among the Javanese elites and the Chinese was due to its leanings towards eastern esotericism. For the Javanese elite, eastern esotericism referred to the Saivite and Buddhist philosophy of old Java. This philosophy also attracted many educated Dutch colonial administrators (Florida, 1995, pp. 27–28). For the Chinese, it was related to Chinese traditional beliefs. Nugraha writes that in the congress held on 1–2 April 1923, The Theosophical Society encouraged the Chinese to return to the teachings of their ancestors (1995, p. 32). An increasing number of wealthy Chinese joined The Theosophical Society, and many became important members as they supported the society financially. Some Chinese theosophists who had a deep interest in Buddhism began to revive it, although it was still mixed with Daoism and Confucianism. One of them was Kwee Tek Hoay, who published the bulletin Moestika Dharma (The Jewel of Dharma) in 1932.

By the mid-20th century, The Theosophical Society started to lose its lustre. It became the target of ideological attacks from the indigenous community, Muslims and Christians alike. They considered theosophy an occultism and a syncretistic belief of various religions. However, Buddhism continued to grow, due to the relentless efforts of some prominent Buddhist monks – among them, Bhante Ashin Jinarakkhita (who was of Chinese descent) and Bhante Girirakkhito (a local Balinese) – in spreading the Dharma in Indonesia.

Although there are natives who have embraced Buddhism, “the vast majority of the Buddhists are indeed ethnic Chinese” (Suryadinata, 2003, p. 124). Buddhism in Indonesia is not only a minority religion, but also one that is associated with a Chinese ethnic minority – and hence is often labelled as a Chinese religion. Although being labelled as a Chinese religion might not have been a problem during the colonial era, the Chinese were seen as allies of the colonialists after Indonesia’s independence. This was in spite of the fact that only a handful of the Chinese people had actually supported colonial rule and that many had instead joined the Indonesian nationalist movement. During the New Order regime (1966–98), the government adopted discriminatory policies against the Chinese.

Furthermore, Chinese culture was depicted as having destructive influences and as being inappropriate for Indonesians. In this political environment, the association with the Chinese was detrimental for Buddhism. In order to survive and grow in post-independence Indonesia, Buddhism needed to be able to attract other ethnic groups.

How does Buddhism in post-colonial Indonesia dissociate itself from the label of being a primarily Chinese religion? In no small part because of the historical entanglements described above, contemporary Buddhism has to show that it is a religion that transcends ethnic boundaries.

Transcending Ethnic Boundaries

Studies in the social sciences show that religion and ethnicity are closely related. In her study, Kuah-Pearce asserts that in the official categorisation in Singapore, the Chinese are associated with Buddhism/Daoism/Shenism, the Malays with Islam and the Indians with Hinduism, even though there are Chinese, Malays and Indians who do not embrace the religions associated with their ethnicity (2009, pp. 136–137). While the link between religion and ethnicity may not reflect the reality that members of a certain ethnic group may not belong to the religion associated with that group, religion has the capacity to socially organise groups of individuals, and religious beliefs and practices can create and strengthen communal bonds among members of the same faith (Durkheim, 1995, p. 41). These communal bonds, created and strengthened through religious rites and practices that transmit cultural values and tradition, can contribute to the preservation and development of ethnic identity.

As the majority of Buddhists in Indonesia are Chinese, in pre-independence Indonesia, many Chinese Buddhist temples played a role in preserving Chinese cultures in Indonesia. However, due to the wave of nationalism that followed the proclamation of the new state of Indonesia in 1945 and the growing anti-Chinese sentiment during the New Order period, Buddhism had to adjust itself to the new political climate. It wanted to be regarded as a universal religion, and one way to accomplish this was to disassociate itself from being labelled as a Chinese religion.

As the Buddhists in Indonesia were predominantly Chinese, and thus Buddhism was also rooted in Chinese culture, Chinese traditional holidays were celebrated as ethno-religious celebrations. In order to receive state recognition, Buddhism had to modify its Chinese-Buddhist rituals and practices. This modification of rituals and practices may find religious justification in the Buddhist belief in impermanence. Hence, everything can be modified and adjusted, depending on the circumstances. Chinese traditional celebrations, which used to be held as an ethno-religious activity, have been appropriated as Buddhist rituals. Many Chinese traditional celebrations fall in the first or the fifteenth day of the month of the lunar calendar. This calendrical cycle fits with the calendrical cycle of the Buddhist days of Uposatha. Thus, Chinese traditional celebrations are now celebrated as Uposatha days, not just as Chinese traditional rituals per se.

The appropriation of Chinese rituals as Buddhist rituals found support in the state-sponsored Buddhist movement, where the New Order regime introduced “modern” and “proper” Buddhism, not Buddhism accompanied by Chinese ritualism. This movement was also propelled by the fact that many Indonesian Buddhist monks underwent religious training in Sri Lanka and Thailand. They brought Theravada Buddhism to Indonesia along with its modernist ideas. Theravada’s modernist ideas even gained currency among the educated and the intellectual Chinese Buddhists who wanted to “purify” Mahayana Chinese Buddhism and rid it of its “non-religious traditional” elements.

An adaptation was also made to the liturgy. Although the New Order regime outlawed the use of the Chinese language and the public display of Chinese culture, Mahayana Chinese Buddhism provided the Chinese with a legitimate space for culturally Chinese rituals and practices. The liturgy was allowed to be conducted in Chinese. The Sutra was permitted to be chanted in Chinese. However, in order to accommodate the political situation, a Sanskrit version of the Sutra was introduced and used in the liturgy. To make it even more Indonesian, Indonesian translations were also provided. In Theravada temples, the Pali Sutta was chanted in its original Sanskrit, and then followed by its Indonesian translation.

In the process of adaptation, the Chinese Buddhists showed resistance as well as accommodation under the pressure of the “Indonesianisation” of Buddhism. The preservation of Chinese traditional celebrations and the use of the Chinese language served as a strategy of resistance that Chinese Buddhists used to express their ethnic identity. However, they also had to compromise as the process of “Indonesianisation” was inevitable and overall positive for the growth of Buddhism in Indonesia. It would make Buddhism more universal, instead of being identified as an ethnic religion, by giving emphasis to the religious aspects of the celebration – for example, Uposatha. The emphasis on Uposatha could create a new sense of Buddhist identity, and at the same time preserve the ethnic nuances of the celebration. To highlight the “Indonesian” content of the Buddhism practised by the Chinese, the Indonesian language, along with other languages important in Buddhism such as Chinese and Sanskrit, was also used.

However, the fall of the New Order regime in 1998 brought winds of change. The change of national leadership in 1998 opened a new chapter in the lives of the Chinese Indonesians, who were accustomed to feeling oppressed during the 32 years of the New Order administration. They found a channel to reclaim their sense of ethnicity. Since then, they have regained their space in public life. Chinese cultural celebrations have received a new lease of life in Indonesia, and the non-Chinese show greater acceptance towards all things Chinese.

Post–New Order Buddhism

The openness and acceptance of Chinese culture in post-New Order Indonesia has also influenced the religious sphere of the Chinese community. Chinese Christians and Chinese Muslims have begun to show interest in ethnic traditional celebrations. For example, the Chinese New Year is also celebrated in some churches and mosques where there is a substantial number of Chinese members. Chinese Buddhists have also begun to celebrate Chinese traditions openly, as well as incorporate the rituals of Chinese traditional religion in their Buddhist practices.

However, the modernist and scripturalist Theravadins question these practices. While they do not reject Chinese traditions and rituals and can accept the celebration of Chinese traditions – just as the Chinese may embrace other religions – they do not want Buddhism to blend with Chinese traditional religions and rituals. This creates a kind of tension between the religious elements and the non-religious, ethnically Chinese elements for the Chinese Buddhists in Indonesia.

How the Chinese Buddhists negotiate Buddhism and Chinese traditional rituals can be drawn from their interpretations of these rituals. Both the traditionalist (Mahayana Chinese) and the modernist (Theravada) Buddhists view Chinese traditions as a way of accumulating and generating merit, and are, for some, a way of worshipping gods and asking for divine blessings. But this also is the point of contention between the traditionalist and the modernist: the former places emphasis the symbolic meaning of the rituals, which they believe are in line with Buddhist teachings, while the latter believes that rituals are not part of the Buddhist religious tradition and cannot be used for generating merit.

An example of the contention between the traditionalist and the modernist are the food offerings made to the image of Buddha. The traditionalists say that in Chinese culture, food offerings are a traditional ritual way of showing devotion and respect. Thus, it is acceptable to do that in Buddhism. The modernists, however, think differently: such offerings are improper because they deviate from the teachings of Buddha, which emphasises logic and reasoning in search of truth, as seen in the Buddhist term of ehipassiko.2

Other things that trigger controversies are rituals such as celebrating religious holidays, and funeral rites. According to the modernists, there are many unnecessary aspects of the rituals that are not in line with Buddhist teachings. But in the traditionalists’ view, Buddhism is open to both local tradition and culture. A Chinese Buddhist can be a Buddhist and a Chinese at the same time. When a Chinese converts to Buddhism, it does not mean that he has to detach himself from his cultural background. The influences of Chinese cultural traditions are acceptable, as long as those rituals do no harm. This example shows that the importance of rituals depends on the religious orientation of each particular Chinese Buddhist, the different Buddhist schools of thought. Those with modernist leanings will view rituals as religiously improper, while traditionalists will emphasise the symbolic meaning of the rituals.

The controversies surrounding the influence of Chinese cultural traditions on Buddhism urge Chinese Buddhists to negotiate the cultural and the religious. In doing so, they transform and recast their ritual and religious practices through privatising the rituals that might trigger tensions. The rituals are separated from the religious, but are still practiced as cultural or traditional elements. In celebrating the Chinese New Year, for example, Chinese traditional rituals are conducted as private affairs, whereas the religious rituals for celebrating it (chanting sutra to invoke blessings) are conducted as public affairs.

Through transforming and recasting their ritual and religious practices, Chinese Buddhists are able to resist demands that they stay away from their traditional ritual practices. Like others who use religion to justify their stance, the Buddhist teaching of open-mindedness is often cited as a justification for Chinese Buddhists.

Conclusion

The trajectory of Buddhism in contemporary Indonesia cannot be separated from the “Chinese” factor. Although it was one of the religions of ancient Indonesia, Buddhism is often seen as a Chinese religion. This is due to the fact that it was the Chinese who reintroduced Buddhism after it had been dormant for a few hundred years, and the particular practice of Buddhism that the Chinese brought was a blend with Chinese traditional beliefs. The arrival of the Dutch theosophists in Indonesia revived interest in Buddhism. Yet, the majority of Buddhists are still ethnic Chinese and Buddhism in Indonesia remains heavily influenced by Chinese culture.

At first this did not create any problems. However, because of the wave of nationalism and growing anti-Chinese sentiments during the New Order regime, Chinese cultural influences in Buddhism became liabilities. The Chinese Buddhists thus needed to conform to the new social and political reality. Believing in the Buddhist teaching of impermanence, they adapted their rituals and practices. Rituals became a political tool for expressing their religious and ethnic identity.

The fall of the New Order regime in 1998 changed the Buddhist landscape in Indonesia. Buddhism imbued with Chinese tradition started to re-emerge. This triggered tensions within the Chinese community, especially between the traditionalists and the modernists. Once again, the Chinese Buddhists had to negotiate between the religious and the traditional cultural elements in their religion. In their negotiation, they used the Buddhist idea of open-mindedness to separate the religious and the cultural, and yet practise both at the same time. The cultural elements are practised “offstage” in the private sphere, while they allow the religious ones to be the “public transcript” of their beliefs. In this way, they transformed and recast their beliefs to come to terms with the problems created by the distinction between the religious and the cultural. By these means, they express both their religious and ethnic identities.

The author acknowledges with thanks Professor Esther H. Kuntjara from the Department of English, Petra Christian University for reviewing the article.

Lee Kong Chian Research Fellow 2010

National Library

REFERENCES

Barnes, G.L. (1995, October). An introduction to Buddhist archaeology. World Archaeology, 27 (2), 165–182. Retrieved from JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website.

Bowen, J.R. (1993). Muslims through discourse: Religion and ritual in Gayo society. Princeton: Princeton University Press. (Call no.: RSEA 297.095981 BOW)

Durkheim, E. (1995). The elementary forms of religious life. New York: The Free Press. (Call no.: 306.6 DUR)

Faxian. (1886). A record of Buddhistic kingdoms: Being an account by the Chinese monk Fa-hien of his travels in India and Ceylon (A.D. 399–414) in search of the Buddhist book of disciple. Islamabad: Lok Virsa. (Call no.: R 204.3438 FAH)

Florida, N.K. (1995). Writing the past, inscribing the future: History as prophesy in colonial Java. Durham: Duke University Press. (Call no.: RCLOS 959.82015 FLO)

Hefner, R.W. (1983, November). Ritual and cultural reproduction in non-Islamic Java. American Ethnologist, 10 (4), 665–683. Retrieved from JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website.

Iskandar P. Nugraha. (2001). Mengikis batas timur dan barat: Gerakan theosofi dan nasionalisme Indonesia [Eradicating the boundaries between the east and the west: Theosophical movement and nationalism in Indonesia]. Jakarta: Komunitas Bambu. (Call no.: Malay RUR 299.934 NUG)

Kuah-Pearce, K.E. (2009). State, society and religious engineering: Towards a reformist Buddhism in Singapore. Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. (Call no.: RSING 294.337095957 KUA)

Mulders, N. (2005). Mysticism in Java: Ideology in Indonesia. Yogyakarta: Penerbit Kanisius. (Call no.: RSEA 291.422095982 MUL)

Salmon, C., & Lombard, D. (2003). Klenteng-klenteng dan masyarakat Tionghoa di Jakarta [Chinese temple in Jakarta]. Jakarta: Yayasan Cipta Loka Caraka. (Call no.: Malay R 294.3435 SAL)

Shangharakshita. (2001). A survey of Buddhism: Its doctrine and methods through the ages. Birmingham: Windhorse Publication. (Call no.: R 294.3 SAN)

Suryadinata, L. (2004). The culture of Chinese minority in Indonesia. Singapore: Marshall Cavendish International. (Call no.: RSING 305.89510598 SUR)

UNESCO. (2005). The restoration of Borobudur. Paris: Unesco Publishing. (Call no.: RSEA 726.143095982 RES)

Yi, J. (2007). A record of the Buddhist religion as practised in India and the Malay Archipelago (A.D. 671–695). [Whitefish, Montana]: Kessinger Publishing. (Call no.: RSEA 294.363 YIJ)

NOTES

-

A stupa is a dome-shaped structure used for keeping Buddhist relics. However, in its development, it has become a symbol of Buddhism. ↩

-

Ehipassiko is a Pali word that literally means “come, see and prove it”. This word refers to the Buddhist teaching that encourages people to use logic and reasoning with mindfulness in search of truth, and not to use blind faith. ↩