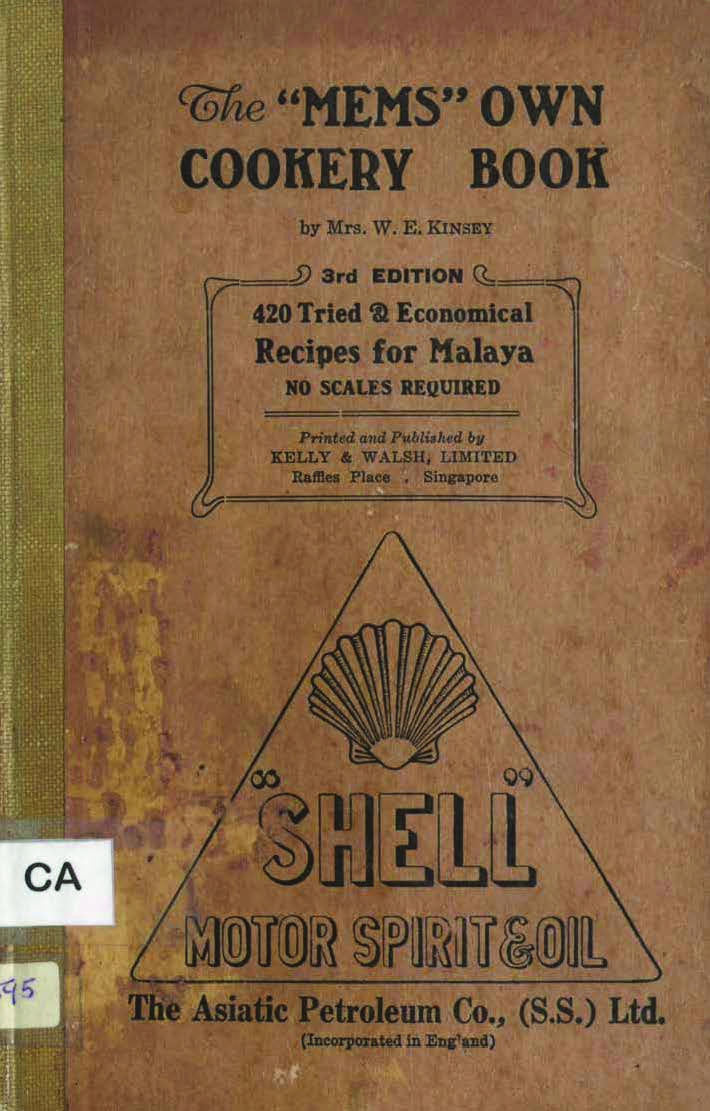

Malayan Cookery Books: The “Mems” Own Cookery Book (1929)

Senior Librarian Bonny Tan delves into The “Mem’s” Own Cookery Book (1929).

— [Untitled]. (1922, May 5). The Straits Times, p. 10, NL 494

A Colonial Family in Malaya

Much more is known of Mr Kinsey and his family than of Mrs Kinsey herself. William Edward Kinsey’s father had come from Liverpool to Malaya in 1892 to manage the Pahang Exploration and Development Company. The company had set up several sawmills in the midst of violent local reactions to the presence of the British. W.E. Kinsey, aged 22, joined his father in 1898. In 1902, he switched to the government service as Inspector of Mines in Negri Sembilan and remained a civil servant until his retirement in 1925 as Deputy Conservator of Forests of Negri Sembilan and Melaka.

What is known today about Mrs Kinsey is that she could cook! “Her skill as a maker of delicious dishs [sic] was well known. She did her own cooking on an oil-stove on the back verandah behind her dining room.”1 This was considered unusual as “Mems”2 usually had a cook and servants to do the actual kitchen work. She was also known for her fruit preserves and had been recognised by the Wembley Exhibition for an exhibit of pickles, chutney and jams made of Malayan fruit.3 Again, her determination to make her own preserves won her admiration amongst those who reviewed her recipes almost a decade later. “What strikes me is that a European ‘mem’ should have found the time to make kundangan chutney. European women today have just as much spare time as they had in Mrs Kinsey’s day – perhaps more, if you take into account the car and the telephone and provisions delivered at your door – but can you see them making kundagan chutney in their own kitchens?”4 It was her passion for churning out these dishes by herself that enriched every one of her recipes.

Colonial Food Conditions

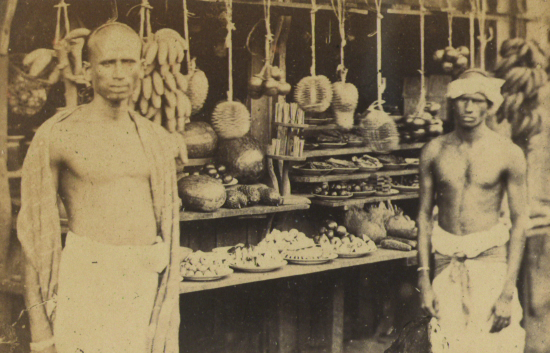

Mrs Kinsey first published The “Mems” Own Cookery Book in 1920. The preface notes that the five years, from 1915 to 1919, of testing the recipes in Seremban where the authoress lived, was a “difficult period”. The outbreak of World War I in Europe led to food shortages and inflated prices especially where luxury food items from the West were concerned. In fact, a certain “Gadfly” published The Slump Cookery Book in 1922 under the Methodist Publishing House to “show the mem fresh from home how to be most pleasantly economical… in these hard times”.5 Others in the East resorted to purchasing and cooking local meats, seafood and vegetables as an alternative to using imported foods to help manage their dwindling finances.6 This sense of frugality is reflected in Mrs Kinsey’s recipes where she often gives the estimated cost of the main ingredient and suggests local alternatives as well as pointing to local Asian stores where the ingredients may be purchased much more cheaply.

The war, however, brought a new appreciation of good cooking as many young British soldiers who had served in France began to savour the richness of French cuisine and in turn, noted the lack of it in their local meals.7 Improved technologies during this time allowed a wider range of food to be imported and prepared. Mrs Kinsey suggests a number of recipes using tinned foods,8 a process that had long been a means of preserving food from back home. Gas cooking was introduced to Malaya in as early as 1900,9 and was then promoted as an economical means of food preparation. However, it was refrigeration that revolutionised the kinds of dishes served in homes and restaurants. Foods previously vulnerable to the tropical climate could now remain fresh on the long sea journey to the East.

The Cold Storage, a famed supermarket chain today, was registered in 1903. Its first retail shop front along Orchard Road opened in 1905. Its first retail branch in Kuala Lumpur was opened in 1910, and soon after in various other cities throughout the Malay States. The opening of Cold Storage meant not only easier access to frozen foods,10 but also the availability of Western-style food products11 which in turn transformed the marketing habits of the expatriate wife. Now the “mems” could shop at these upmarket stores while the cooks did their marketing at the wet market. So significant were the company’s products in preparing Western meals that a number of Mrs Kinsey’s recipes are prefixed with the adjective “Cold Storage” such as those for bloaters, haddocks, kippers (p. 28) and pheasant (p. 37). In fact, Cold Storage is the main establishment mentioned for unique provisions such as the Cold Storage sausages in the recipes for beef and sausage roll (p. 52), stuffed galantine of fowl (pp. 69–70) and plain sausage rolls (p. 89).12

Colonial Meals and Local Cooks

Mealtimes for the colonial family were often painfully monotonous, with the same dishes served up again and again, mostly for want of a variety of ingredients as well as a lack of skill. This was especially so in the estates “where the fare is usually simple and monotonous and the Chef equally so”.13 In an article in the Singapore Free Press14, “Makan ada” encouraged the lady of the house to make a list of a variety of dishes, “then armed with this catalogue daily confront the Chinese Soyer [the local cook], and turning a deaf ear to all remonstrances say calmly, ‘Mesti bikin itu macham, lu ada pandai, choba.’ [‘You must follow this, you are clever enough, try it.’]”15 The colonial cookery book became an important aid in training both “mem” and her cook to whip up new and delicious dishes to tantalise the colonial family’s taste buds using the same basic ingredients. Thus, Mrs Kinsey’s book has seven recipes for ikan kurau alone (pp. 20–23), some merely distinguished by numbers, alongside 24 recipes for sauces (pp. 111–118) and nine recipes for preserves, pickles and chutneys (pp. 120–125). She even has a listing of at least three recipes entitled “Remains of Cold Fish” (pp. 25–26) and “Remains of Cold Fowl” (pp. 84–85) each, along with several others that use leftovers as the main ingredient.

Besides catering to daily familial appetites, cooking amongst the expatriates in Malaya centred on the colonial dinner party. Leong-Salobir notes: “The colonial dinner party stands out as the social function that involved the most distinctive [social] characteristics and these were practiced from the earliest years of colonization right up to independence” (Leong-Salobir, 2011, p. 29). The responsibility of dinner entertainment fell to the women whether they were the governor’s wife or the merchant’s. They, however, had an army of domestic servants who assisted in the purchase, preparation and presentation of these lavish meals.

The cookbook provided recipes for both domestic pleasure and official function. Additionally, it often gave useful advice for managing and supervising local cooks. In her preface, Mrs Kinsey writes: “The object of this book is to help those ‘MEMS’ who are keen on taking advantage of the possibilities of catering in this country, also with the hope that it will generally assist to combat the pernicious policy of the native cooks who not only overcharge in the prices of local commodities, but generally will not produce them, or attempt to raise non-existent difficulties.”16

Local cooks were often not seen in a positive light when it comes to purchasing ingredients, cooking, or even revealing the secrets of a local dish to their “Mems”: “It is true that the the average Chinese cook becomes as inscrutable as the Sphinx when asked by a ‘foreign devil’ for a recipe and even when under exceptional circumstances, he is induced to part with one he generally leaves out a vital ingredient, so that the American seldom really obtains the true Chinese dish. That is why many who have experimented with Chinese cooking at home complain it does not taste the same as the dishes served in the Chinese restaurants.”17

They were seen as stubbornly inadequate and thieving. They would even steal things such as the drippings of a roasting joint: “The native cooks’ idea of roasting joints is to sprinkle over freely Chinese sauce and salt… even if you give him good dripping for the joint, if he is not watched he will still do the same and steal part of the dripping too” (p. 170).

A reviewer of the book even suggests that Mrs Kinsey’s concluding tips on cooking “should be translated into Chinese for the benefit of the Autocrat of the Kitchen”,18 a reference to the Chinese cook. The book was highly recommended for “local housekeepers who believe in having a say in their own households and do not trust their’s and the Tuan’s digestions to the tender mercies of Cookie”.19

Colonial Dishes and Malayan Recipes

Mrs Kinsey’s cookbook presents dishes familiar to the British colonial palate – an amalgam of Western boiled and baked cheese dishes alongside curries and kedgerees – influences from British India that had become incorporated into the British dinner menu.

The 420 recipes are organised into broad categories, reflecting the main dishes eaten by expatriates: soups, fish, roasts, poultry and game, vegetables, entrees, hors d’oeuvres, potted meats, sandwiches, sauces, pickles and preserves, forcemeats, puddings, cakes and pastry. Each section lists the recipes alphabetically.

Besides describing some classic dishes such as scrambled eggs (p. 90) and cheese on toast (pp. 56–57), there are also less common dishes such as turtle soup (p. 12), sheep’s head broth (p. 11), pig’s cheek boiled (p. 80), sheep’s tongues braised (p. 90), sheep’s brains on toast or with bacon (p. 165) in the book. She also provides recipes for invalids and the ill such as chicken jell and chop (p. 62). Occasionally she even gives the seasonal availability of an item, noting for the reader’s benefit that “[mushrooms] may be bought at all Chinese kedais [stores] all the year round” (p. 46).

Of particular interest are her descriptions of Malayan dishes. Her recipe for “satai” (pp. 87–89), for example, spans three pages, beginning with the roasting of the nuts in a flat tin, thereafter flaking their skins off by rubbing them with a clean cloth. Then, she recommends setting up a good fire, preferably in a Chinese earthenware pot and basting “the sticks with a fowl’s feather” (p. 88). Even serving directions are given, detailing accompaniments such as rice, finely chopped pineapples and a cold peanut sauce although she notes that the Malays prefer to serve it with the much more familiar ketupat, a rice dish that is a “stiff square, wrapped in a leaf and usually sold one cent per piece” (p. 89). She also recommends that the dish be served with a soup – “if fowl sarti [sic], meat soup, if beef sarti clear or poultry soup” (p. 89). She further adds that “Sarti must be served very hot and sauce cold” (p. 89). Other local Malayan recipes she includes are rundang (rendang, a meat stew; p. 86), dry curry puff (p. 65) and ayam bakar (barbecued chicken; p. 68), which she also names “fried fowl in cocoanut”.

As promised, she uses many local ingredients, particularly for fish such as ikan bawal, ikan merah and ikan kurau where she describes both Western and Eastern styles of preparation. Such localisation of recipes gave the cookbook an edge over those written for audiences of a different climate who often had ingredients that were less likely available in the tropical climate.20

Local names or nicknames for ingredient kachang goring (Malay for fried nuts) give us colloquial insights into these food items. Of interest are Mrs Kinsey’s useful tips into food preparation, much of which may be forgotten today – “Add egg shell to help clear soup and strain through muslin”; “Always remember when cooking celery, to leave the lid off the pan otherwise there will be a slightly bitter flavour”.

Within the first few months of the publication of Mems, the cookbook was sold out and a second print was scheduled for 1929, with a third released the following year. Its popularity was also reflected in advertising within the book such as those for Bear Brand Swiss Milk, normally used in the cookbook’s recipes.21 In 1931, Mrs Kinsey published another cookbook, Next Meal Cook Book,22 which was sold as a double volume with Mems.

The “Mem’s” Own Cookery Book is from the collection of rare and historical imprints at the National Library Singapore. A second edition of Mem’s can be found in the Rare Book Collection on Level 13. A copy is also accessible on microfilm (NL 9852).

The author acknowledges with thanks Ai Ling Devadas, Editor of the Singapore Food History website for reviewing the article.

Senior Librarian

Lee Kong Chian Reference Library, National Library

REFERENCES

Barber, A. (2007). Malaysian moments: A pictorial retrospective. Kuala Lumpur: AB&A. (Call no.: RSEA 959.5 BAR)

Goh, C.B. (2003). Serving Singapore: A hundred years of Cold Storage, 1903–2003. Singapore: Cold Storage. (Call no.: RSING 381.148095957 GOH)

Growing popularity of Chop Suey. (1913, March 1). Weekly Sun, p. 10. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Humble, N. (2005). Culinary pleasures: Cook books and the transformation of British food. London: Faber.

Leong-Salobir, C. (2011). Food culture in colonial Asia: A taste of empire. Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon: New York: Routledge. (Call no.: RSING 394.12095 LEO)

Lighter dinner. (1920, September 27). The Straits Times, p. 10. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Makan Ada. (1908, May 26). Careful cookery. The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, p. 1. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Notes of the day: Malay chutney. (1939, July 11). The Straits Times, p. 10. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Olver, L. (2011, July 4). The food timeline. Retrieved from Foodtimeline.org. website.

Page 2 Advertisements Column 1: Katz Brothers. (1900, March 30). The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, p. 2. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Some new books. (1922, May 6). The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, p. 9. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

The literary page – new books reviewed: Recipes for Malaya. (1930, January 31). The Straits Times, p. 17. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

The slump cookery book. (1922, May 17). The Straits Times, p. 8. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

The wanderer. (1932, April 24). Mainly about Malayans. The Straits Times, p. 4. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

The wanderer. (1933, September 10). Mainly about Malayans. The Straits Times, p. 5. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Tregonning, K.G. (1967). The Singapore Cold Storage, 1903–1966. Singapore: Cold Storage Holdings Ltd. (Call no.: RCLOS 664.02852 TRE)

Untitled. (1902, June 25). The Straits Times, p. 5. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Untitled. (1922, May 5). The Straits Times, p. 10. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Untitled. (1925, April 7). The Straits Times, p. 8. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Untitled. (1925, October 9). The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, p. 16. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

NOTES

-

“The wanderer”. (1933, September 10). Mainly about Malayans. The Straits Times, p. 5. ↩

-

“Mem” was a term of address used by employees of a colonial family for the lady of the house. It is a corruption of “Madam” and often used in conjunction with “Sahib” the Indian term of address for the man of the house – thus “mem” is a shortened form of “memsahib” commonly used amongst the British colonials in India. ↩

-

Untitled. (1925, October 9). The Singapore Free Press, p. 16; Untitled. (1925, April 7). The Straits Times, p. 8. ↩

-

Notes of the Day: Malay chutney. (1939, July 11). The Straits Times, p. 10 ↩

-

The slump cookery book. (1922, May 17). The Straits Times, p. 8. (The National Library does not have a copy of this title). ↩

-

Europeans in the east. (1919, October 22). The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, p. 12. ↩

-

Lighter dinner. (1920, September 27). The Straits Times, p. 10. ↩

-

For example her recipes for tinned salmon (p. 105) and sardines (p. 110). ↩

-

An advertisement of the Katz Brothers in The Singapore Free Press dated 30 March 1900 showed it offered gas stoves for sale. ↩

-

Cold Storage opened in Kuala Lumpur in 1910; in Singapore, by 1916, it was manufacturing ice. (Leong-Salobir, 2011, p. 31) ↩

-

Leong-Salobir, 2011, p. 31. ↩

-

However, she does mention Messrs H. Bolter for good French dried sausages (p. 105). ↩

-

Some new books. (1922, May 6). The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, p. 9. ↩

-

The article “Careful cookery” (26 May 1908) elaborates further on how new ideas, recipes and techniques can help the Hylam (Hainanese) cook in the employ of colonial families reinvigorate the flavours and variety of dishes served in the home. ↩

-

“Makan ada”. (1908, May 26). Careful cookery. The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, p. 1. ↩

-

Growing popularity of Chop Suey. (1913, March 1). Weekly Sun, p. 10. ↩

-

Some new books. (1922, May 6). The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, p. 9. ↩

-

The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, 6 May 1922, p. 9. ↩

-

Bear Brand Unsweetened Swiss Milk advertising in the month of March 1930 in The Straits Times. ↩

-

Unfortunately, the Library does not hold a copy of this. ↩