Using Graphic Novels to Teach English Language in Secondary Schools in Singapore

Novelist Clarence Lee investigates the effectiveness, plausibility and implications of using graphic novels in the teaching of English.

In the classroom, books can be used as media for transmitting knowledge, studied as objects for their own value – as might happen in a literature lesson – or take students on a journey with their imagination. Educators have often debated about introducing new books into the classroom because they have different views as to which books fulfil those three roles well, and the debates often reveal what books are considered culturally or politically acceptable (Carter, 2008, pp. 52–55). Most educators have shunned graphic novels because they supposedly lack merit as a medium for knowledge or skills transmission or are unfit for study as artistic objects (ibid., pp. 49, 54). But do these assumptions have any rational basis? To see if this is the case in Singapore, a study was conducted in Singapore to look at the effectiveness of using graphic novels to teach descriptive writing in English Language lessons in a neighbourhood secondary school.

Graphic novels – also popularly known as comics – comprise pictures and words.

Children and adults have been reading them for over a century because they combine words and visual images to stimulate the imagination in ways that mere words are probably unable to do.

Most educators have been using books as media to assist in the teaching of skills or content. Books such as classical novels or textbooks have always dominated education syllabi because they are safe choices as they have been used by many generations of teachers and are perceived to have more direct instructional value. The content of textbooks is similar to that which appears in national or international high-stakes examinations. Literature texts may be selected because educators believe that they are precious objects that should be studied for their cultural value or because they contain some significant moral messages. A book list published annually by the University of Cambridge Local Examinations Syndicate determines the texts taught to Secondary Three, Four and Five students in Singapore. The literature texts are often not written by Singaporeans but by more esteemed writers who are usually from the West. Although the teaching profession deals with the young on a daily basis, it is notoriously resistant to renewal. Shakespeare, for example, has remained in many education syllabi for as long as anyone can remember.

Literature Review

On the other hand, teachers tend not to use graphic novels because they are seen to be less useful for teaching. Educators perceive them as merely focusing on the supernatural and/or horror, and they are merely “expressions of the male power fantasy” or tasty morsels that will lure students away from reading other supposedly more serious genres of literature (Bucher & Manning, 2004, p. 68). Yet there are examples of graphic novels that have received critical acclaim from literary critics. Maus, which is Art Spiegelman’s retelling of the Holocaust, has won the Pulitzer Prize; Barbara Brown, a high-school teacher in America, used the book to teach race relations and to help students understand the core text in their literature syllabus, William Faulkner’s Light in August (Carter, 2007, p. 51).

Many students read graphic novels (Majid & Tan, 2007), yet there seems to be a dichotomy between what they voluntarily read outside of school and the books that teachers use in class. In spite of this, many educators who are willing to go beyond the normal scope of accepted literature in the classroom have often found that using books that engage students’ imagination and interest yields positive results (Downey, 2009, p. 184). Librarians like Michele Goman, Michael R. Lavin and Stephen Weiner have shown that students are very interested in graphic novels (Carter, 2007, p. 50). Research conducted by Frey and Fisher (2004, pp. 19–25) showed the effectiveness of using graphic novels to teach low-ability ninth graders – equivalent to Secondary Three in Singapore – English in an urban American high school. Scholars such as Stephen Cary, Stephen D. Krashen and Jun Liu have conducted research that demonstrated how sequential art like graphic novels aids learners of English as a Second Language (Carter, 2007, p. 50). Many students in Singapore can be considered to belong to this category since they do not usually communicate in Standard English and often use a different language, such as Chinese, Malay or Tamil, when at home.

Examinations will change in the next few years after the 2010 English syllabus has been rolled out in schools. It clearly demands that students be taught the necessary skills for reading multimodal texts (MOE, 2008, p. 9). These are texts that combine words with images, moving images or sound. It is imperative that our students develop multimodal literacy skills because these multimodal texts are what everyone, including adults, has to deal with on a day-to-day basis in every aspect of our lives in both work and play (Kress & van Leeuwen, 1996, p. 3). For example, most of our media is delivered via the internet, television, radio, newspapers or magazines where words always interact with pictures or sounds to produce meaning. Unfortunately, teachers in Singapore are not yet familiar with teaching multimodal literacy, and school literacy practices remain based on the printed word (Kramer-Dahl, 2005, p. 233). If our students are to be expected to become independent, critical thinkers who can analyse these multimodal texts instead of taking them at face value, then we have to make the teaching of multimodal literacy explicit instead of assuming, as we have in the past, either that students will naturally develop multimodal literacy outside of school or that verbal literacy is the only important literacy.

Comics are useful in the classroom for several reasons. The first is that their multimodal nature makes them a perfect means of teaching multimodal literacy. Comics use pictures and words together to generate meaning. The reader cannot rely merely on the words or the images alone to understand the storyline. One extreme example of how a reader could make a mistake by relying only on the words or the pictures is when the words and pictures have divergent effects. This can create a certain kind of irony and it is often used to great effect in political cartoons, which incidentally, are already part of the history “O” Levels examination. Teaching graphic novels with a cross-curricular or interdisciplinary approach can help students make connections between their learning in multiple subjects, with English and history being just two of the more pertinent examples (Carter, 2007, p. 51).

Many students already read comics as they are a part of popular culture (Majid & Tan, 2007). Texts with elements of popular culture seem less foreign to the students than the verbal texts often used in schools and can engage the interest and intellect of students better (Grainger, Goouch & Lambirth, 2005, p. 39). Popular culture in and of itself need not be a bait to lead students on to so-called legitimate works of art, though there is much matter for analysis in advertisements, blockbuster films, horror novels and, even the subject of our investigation, graphic novels (ibid., p. 40).

Reading comics actually requires more complex cognitive skills, since readers have to deal with the interplay of words and pictures, and attempt to construct logical transitions from one panel of a comic to another (Schwarz, 2002, p. 263; Bucher & Manning, 2004, p. 68). In spite of this complexity, many young students who have grown up reading multimodal texts like comics and webpages might actually already possess the necessary skills to manage this complexity, whereas adults who are used to traditional verbal texts might feel frustrated by the lack of a distinct linear progression in a multimodal text.

Dual-coding theory proposes that our brains are reliant on not just verbal processes to produce meaning but on a complex interplay between nonverbal and verbal faculties (Sadoski & Paivio, 1994). Even when reading a purely verbal text that has only words and no accompanying pictures or sounds, our brains create mental images that aid us in imagination and comprehension. The opposite is true when we view pictures without words. In other words, to neglect the training of the visual faculties of our brain with the visual images found in multimodal texts would be to forsake an important aspect of our minds that helps us decode texts that contain only words.

Furthermore, according to theories of multiple intelligences, there are many students who learn more readily through listening, kinesthetic action or viewing images rather than through reading verbal texts, and it is the visual learners who will benefit substantially from the use of multimodal texts like comics (Carter, 2008, pp. 48–49). Our education system has given verbal learners higher esteem for centuries, while the visual, aural and kinesthetic learners have been put at a disadvantage and scorned for their seeming incompetence and stupidity simply because they cannot learn as readily, since schools almost exclusively depend on using words to teach students knowledge and skills (Jacobs, 2007, pp. 19–25).

Using multimodal texts gives students with different strengths a chance to interact and test their theories against each other. Visual learners are often resigned to their fate as slower learners in the education system as they see their more verbally literate peers constantly perform well, while they find the verbal texts used for every lesson insurmountable. With multimodal texts like comics, students can collaborate, and those whose visual literacy had constantly been ignored can now play a more active role in class by helping their classmates. This sort of collaborative learning, which can include elements of peer teaching, can foster a culture of democracy in schools where pupils recognise each other’s strengths and learn that they have to rely on each other (Chai et al., 2011, p. 44).

Research Methodology

The research was undertaken by teachers of Yishun Secondary School. It can be classified as an action research project since the researchers are the actual practitioners on the ground who are looking to improve the knowledge base of their professional community. Although research conducted by academics is more common, action research has a long history as a valid research methodology in the social sciences, especially in the field of education research. It has contributed much knowledge to both the communities of academics as well as those of professional practitioners (Jungck, 2001, p. 340). When conducted in the proper manner, the findings of an action research project do not merely have local relevance but can be generalised for wider populations (Hui & Grossman, 2008, p. 4).

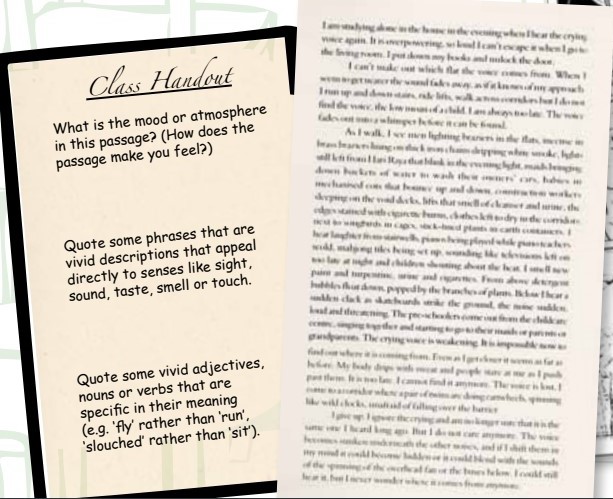

Twenty-three male and 13 female Secondary Two students from the Express stream in Yishun Secondary School participated in this experiment. The hypothesis was that using graphic novels would have a greater effect on teaching pupils descriptive writing skills in an English Language lesson compared to using only a purely verbal text. The pupils had previously learnt the basics of descriptive writing earlier in the year that the research was conducted but not the more advanced descriptive skills that this lesson covered. A pre-test was first conducted in which the students had to write a brief response to the question, “Write a description of your neighbourhood to convey a particular mood.” This was chosen as it eliminated the possibility of assessment bias since it made no assumptions about prior knowledge and no student would be at a disadvantage (Witte, 2011, p. 108).

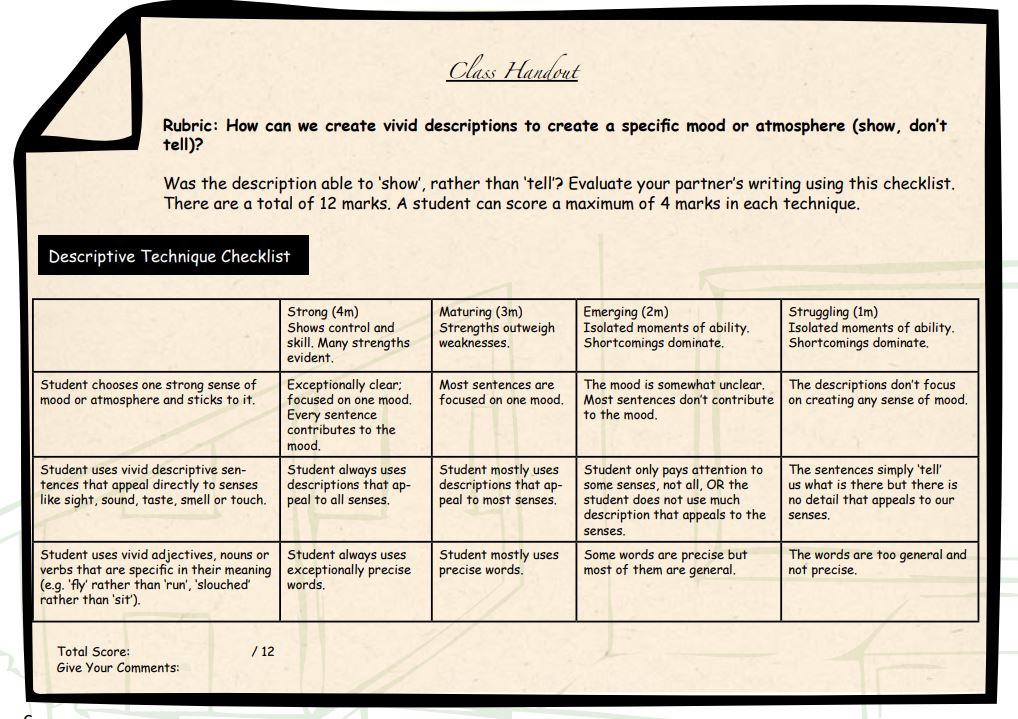

This pre-test was marked using a 12-mark rubric with distinct numerical grades for each fulfilment of the desired skills of descriptive writing. Rubrics contain criteria and performance scales that help students or assessors define the important components of a performance or product. Analytic rubrics divide the criteria into separate scoring sections, whereas holistic rubrics combine the criteria to give a general grade (Witte, 2011, p. 151). In this case, an analytic rubric was used since both student and assessor had to be absolutely sure which particular descriptive skills were areas of weakness or strength. The rubric was designed based on those for creative writing (Witte, 2011, p. 193; Hanson, 2009, p. 106).

To satisfy the conditions for a truly experimental design, we had to assign the students randomly to one Control and one Treatment group, and to make the groups as equivalent as possible. Stratified random sampling of the students was conducted, dividing them into the two groups using their pre-test scores so groups would have an identical mix of students with similar scores (Fraenkel & Wallen, 2006, p. 100). Therefore, it can be assumed that the samples of both groups were mechanically matched and thus equal in their proficiency in descriptive writing (ibid., p. 236).

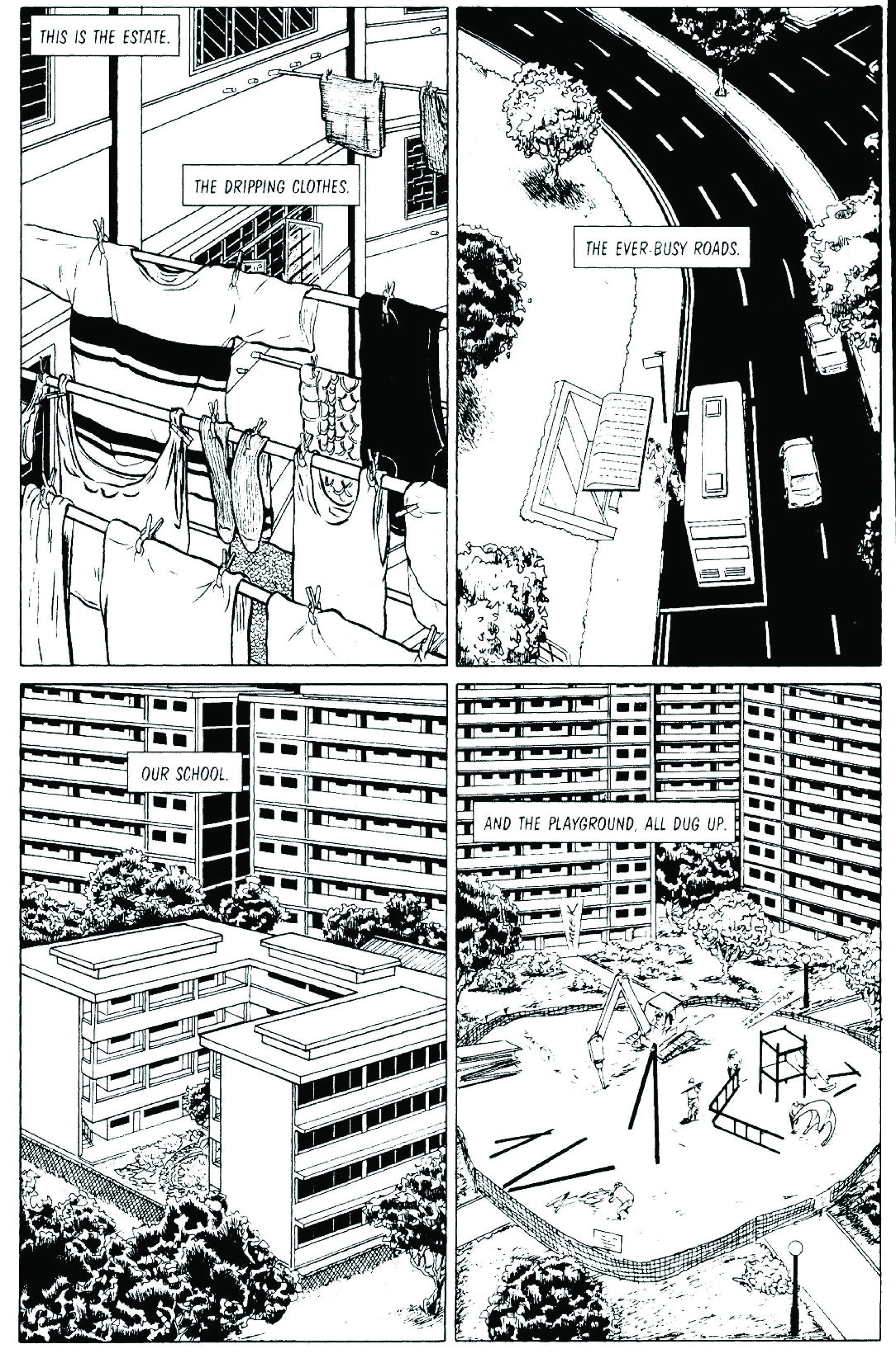

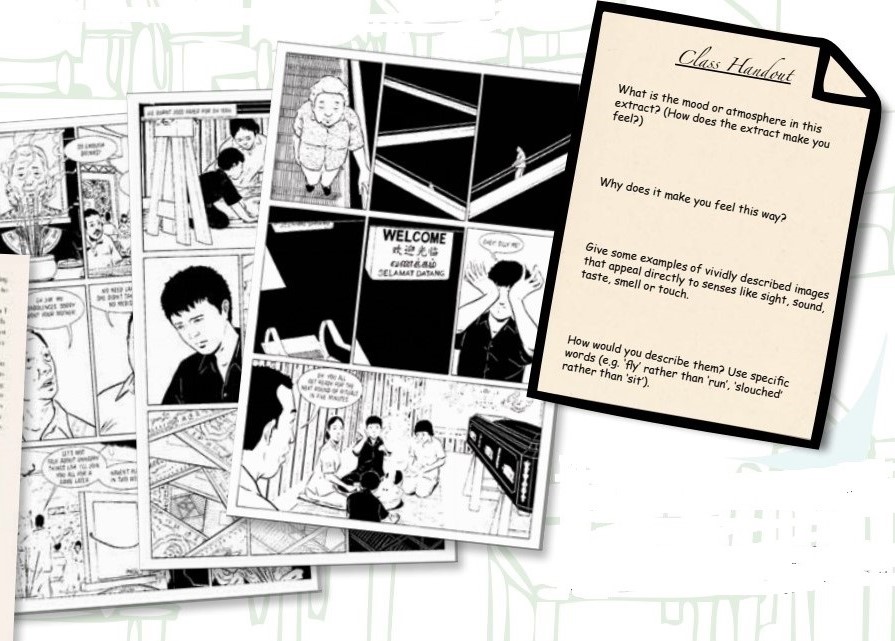

Between the pre-test and the day of the lesson which included the post-test – which was conducted a week after the pre-test – the students were not taught descriptive writing so as to reduce the risk of maturation of their writing abilities. On the day of the intervention, the students were divided into their groups, with the Control group being taught texts from Dave Chua’s novel Gone Case (Chua, 2002), which received the Singapore Literature Prize Commendation Award in 1996 (Lee, 2006). The Treatment group was taught with a graphic novel adaptation of Gone Case, also written by Dave Chua and illustrated by Koh Hong Teng (Chua & Koh, 2010). These texts were chosen because they were closely related in terms of subject matter, namely life in Housing and Development Board neighbourhoods, which incidentally were where most of the students lived. The local setting did not demand the knowledge of foreign slang and it engaged the interest of the students who did not have many encounters with Singaporean literature.

Immediately after the lesson, students in both groups were given a post-test where they wrote brief descriptive responses to the same question given in the pre-test. They were assessed with the same rubric. A survey was conducted after the post-test to find out what the students thought about the lesson.

Data Analysis

Quantitative Analysis of Pre-test and Post-test Results

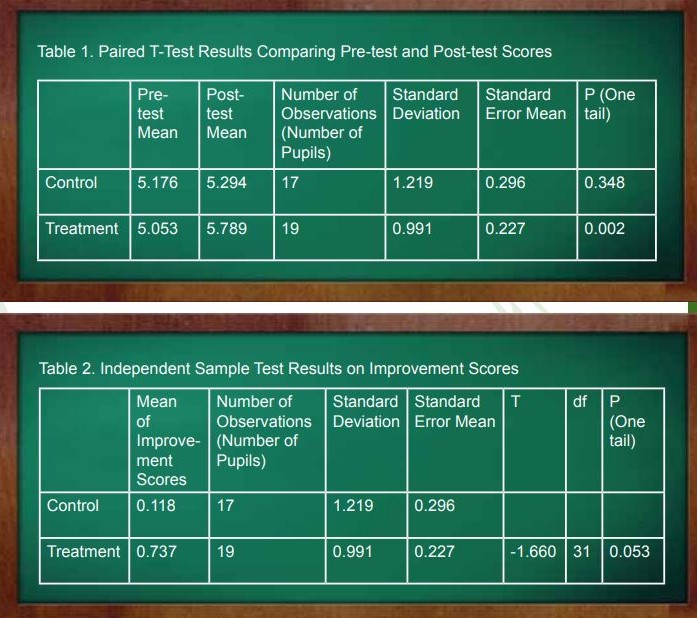

Using the conventional p-value of p≤0.05, a paired t-test comparing the pre-test and post-test scores of the Treatment group shows a statistically significant gain (p=0.002). However, a paired t-test comparing the pretest and post-test scores of the Control group shows no statistically significant gain (p=0.348) (Table 1).

The results of this independent t-test show that the mean for the improvement of the Control group was 0.118, while the mean for that of the Treatment group was 0.737. Considering that the highest possible score is only 12 marks, the difference of 0.619 or 5.16% is relatively large (Table 2).

The hypothesis predicts that the Treatment group would show a greater improvement and that is why we analysed the scores using a one-tailed p-value. Although some would argue that the p-score of 0.053 is slightly above the conventionally desired 0.05, it is close enough that we can reject the null hypothesis, which is that graphic novels would have no larger effect on teaching descriptive writing compared to verbal texts. To not reject the null hypothesis in a case like this would be to commit a Type II error, which is to fail to reject a null hypothesis that is false, since “there is nothing sacred about the customary .05 significance level” (Fraenkel & Wallen, 2006, p. 231). The 0.053 significance level is largely due to the small sample size and a larger sample size is expected to yield a significance level below 0.05. As our results can be considered statistically significant, we can not only accept the hypothesis that using graphic novels had indeed helped in teaching the students in the experiment descriptive writing skills more than using only normal verbal texts, but also generalise these results to infer that using graphic novels can help students learn descriptive writing better than using verbal texts.

Qualitative Analysis of Survey Responses

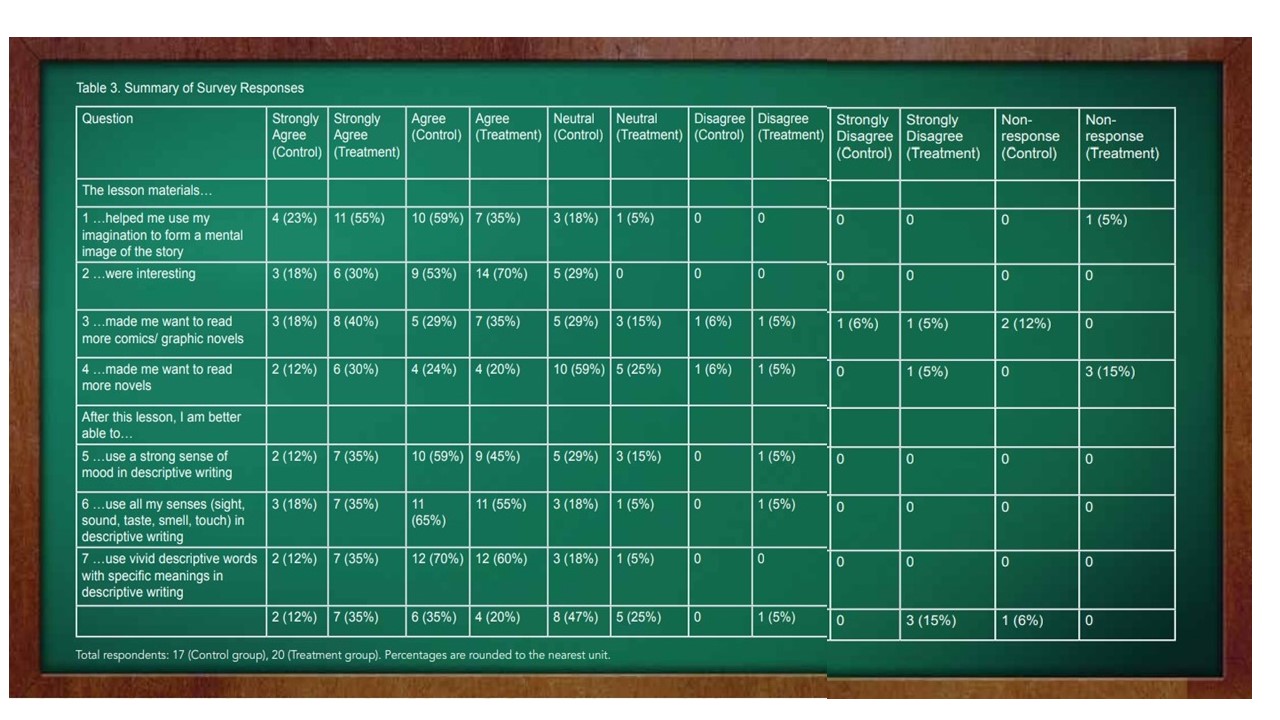

The responses to the survey were summarised and analysed (Table 3).

The survey shows that while students in both groups found the verbal text and the multimodal text from the graphic novel interesting, a larger proportion of students within the Treatment group, which used the graphic novel, agreed that the lesson helped them achieve the learning objectives of improving their descriptive writing (Questions 5, 6 and 7). The responses included, “Through pictures, I can learn better”, “I like the ‘Singapore flavour’ in the comics” and “It helped me to use imagination to include inside the novel. I now can make my novel more interesting and real”. While the survey sample is small and we cannot easily make generalisations on larger populations based on this data, we believe that it can be used to give some indication that the use of graphic novels engaged the imaginations of students in the Treatment group and helped them improve between the pre-test and post-test more than the Control group did.

Limitations

There were a few limitations to the experiment. Only one class of pupils was available for the experiment. The sample size of 36 pupils fits the class size for most Singaporean classrooms, but to generalise with this small group size is an issue. The research had to be conducted within the school’s existing schedule and so a few days after the pre-test, the groups were separated and taught by different teachers – each with two years of teaching experience – in two separate classrooms at the same time. Two students from the Control group were absent on the day of the post-test. The survey had to be conducted a few days after the post-test due to schedule constraints. In addition, the results collected for the Treatment group contained one additional response because this student did not report that he had been absent during the lesson and post-test, and the anonymous nature of the survey prevented the researchers from identifying and removing his response from the consolidated responses.

Conclusion

The findings suggest that graphic novels can be a useful tool to aid learning in the Singaporean classroom. There are significant pedagogical implications. Multimodal texts like graphic novels should not replace traditional verbal texts completely, but they can be used as complements to traditional texts in education (Carter, 2007, p. 51). Considering that students need to develop literacies in reading multimodal texts, educators who wish to meet this need by using graphic novels need to know how to read graphic novels critically and learn how to choose the right resources that readers will appreciate and that will achieve learning objectives (Bucher & Manning, 2004, p. 68). Schools cannot assume that educators will be able to achieve this without training and the provision of resources in the school like a library of graphic novels.

There are implications outside of the classroom as well. Educators and public libraries have a symbiotic relationship and if public libraries stocked more graphic novels, students and educators would have better access to them and be able to read them for pleasure or use them in the classroom. The lack of access to graphic novels, which tend to be relatively more expensive than verbal texts, is one difficulty that educators face when trying to include graphic novels in a curriculum. Schools and libraries can also convince parents of the educational value of graphic novels and reassure them that these can help their children cultivate good reading habits as well as multimodal literacies.

We often distrust the products of popular culture such as comics that children seek voluntarily and enjoy outside of the curriculum (these also include film and animation). These traditional assumptions about how certain genres or text types are useless for education must be reassessed. The research literature has shown that the graphic novel can be an effective medium for teaching knowledge and skills as well as a literary object for in-depth study. The research project at a Singapore school appears to confirm these findings. Part of the graphic novel’s effectiveness arises from its potential for engaging the interest and imagination of the reader. With the right lesson design, any text that can bring the reader on a journey can be used. If we ignore the descriptive and narrative power of graphic novels and continue to teach students the way our generation and theirs have always been taught (i.e., with texts showing nothing but words), then it should be no surprise if they grow up unable to effectively decipher neither pictures nor even words.

Novelist

REFERENCES

Butcher, K.T., & Manning, M.L. (2004, November–December). Bringing graphic novels into a school’s curriculum. The Clearing House: A Journal of Educational Strategies, Issues and Ideas, 78 (2), 67–72. Retrieved from JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website.

Carter, J.B. (2007, November). Transforming English with graphic novel: Moving toward out “Optimus Prime”. The English Journal, 97 (2), 49–53. Retrieved from JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website.

Carter, J.B. (2008). Comics, the canon and the classroom (pp. 47–60). In N. Frey & D. Fisher. (Eds.), Teaching visual literacy: Using comic books, graphic novels, anime cartoons, and more to develop comprehension and thinking skills. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press. (Call no.: 372.6044 TEA)

Cheah, H.S., et al. (2011). Advancing collaborative learning with ICT conception, cases and design. Singapore: Ministry of Education, Educational Technology Division.

Chua, D. (2002). Gone case. Singapore: Ethos Books. (Call no.: RSING S823 CHU)

Chua, D., & Koh, H.T. (2010). Gone case A graphic novel. Book 1. Singapore: s.n. (Call no.: RSING 741.595957 CHU)

Chun, C.W. (2009, October). Critical literacies and graphic novels for English language learners. Teaching Maus. Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy, 53 (2), 144–153. Retrieved from JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website.

Curdt-Christiansen, X.L., & Silver, R. (2011). Learning environment: The enactment of educational policies in Singapore (pp. 2–24). In C. Ward (Ed.), Language education: An essential for a global economy. Singapore: SEAMEO Regional Language Centre. (Call no.: RSING 418.0071 APE)

Curriculum Planning and Development Division. (2010). English language syllabus. Singapore: Ministry of Education. (Not available in NLB holdings)

Downey, E.M. (2009, Winter). Graphic novels in curriculum and instruction collections. Reference & User Services Quarterly, 49 (2), 181–188. Retrieved from JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website.

Fraenkel, J.R., & Wallen, N.E. (2000). How to design and evaluate research in education. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Frey, N., & Fisher, D. (2004, January). Using graphic novels, anime, and the internet in an urban high school. The English Journal, 93 (3), 19–25. Retrieved from JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website.

Grainger, T., Goouch, K., & Lambirth, A. (2005). Creativity and writing: Developing voice and verve in the classroom. Abingdon: Routledge. (Call no.: R 372.6230440941 GRA)

Hanson, A. (2009). Brain-friendly strategies for developing student writing skills. Thousand Oaks: Corwin Press.

Harris, K.R., & Graham, S. (1996). Making the writing process work: Strategies for composition and self-regulation. Brookline: Brookline.

Hui, M.F., & Grossman, D.L. (Eds.). (2008). Introduction. In improving teaching education through action research (pp. 1—6) New York: Routledge. (Not available in NLB holdings)

Jacobs, D. (2007, January). More than words: Comics as a means of teaching multiple literacies. The English Journal 96 (3), 19–25. Retrieved from JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website.

Jungck, S. (2001). How does it matter? Teacher inquiry in the traditions of social science research. In G. Burnaford, J. Fischer & D. Hobson. (Eds.), Teachers doing research: The power of action through inquiry (pp. 329—324). Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Kramer-Dahl, A. (2005, Summer). Constructing adolescents differently: On the value of listening to Singapore youngsters talking popular culture texts. Linguistics and Education, 15 (3), 217–241.

Kress, G.R., & van Leeuwen, T. (1996). Reading images: The grammar of visual design. London: Routledge. (Call no.: RART 701 KRE)

Lee, G. (2006). Dave Chua. Retrieved from Singapore Infopedia.

Majid, S., & Tan, V. (2007, Winter). Understanding the reading habits of children in Singapore. Journal of Education Media & Library Sciences, 45 (2), 187–198.

Malinowski, D., & Nelson, M.E. (2007). Hegemony, identity and authorship in multimoda discourse. In M. Mantaro (Ed.), Identity and second language learning: Culture, inquiry and dialogic activity in educational contexts (159—187). Charlotte: Information-Age Publishing. (Not available in NLB holdings)

Moore-Hart, M.A. (2010). Teaching writing in diverse classrooms K-8: Enhancing writing through literature, real-life experiences and technology. Boston: Pearson. (Not available in NLB holdings)

Sadoski, M., & Paivio, A. (1994). A dual coding view of imagery and verbal processes in reading comprehension. In R.B. Ruddell, M.R. Ruddell & H. Singer. (Eds.), Theoretical models and processes of reading (pp. 582—601). Newark: International Reading Association. (Not available in NLB holdings)

Schwarz, G.E. (2002, November). Graphic novels for multiple literacies. Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy, 46 (3), 262–265. Retrieved from JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website.