Comic Books as Windows into a Singapore of the 1980s and 1990s

Singapore comic books and graphic novels are mediums that allow us to glean a vision of the recent past. Lim Cheng Tju spotlights Unfortunate Lives and Mr Kiasu and unpacks what they reveal about the past two decades.

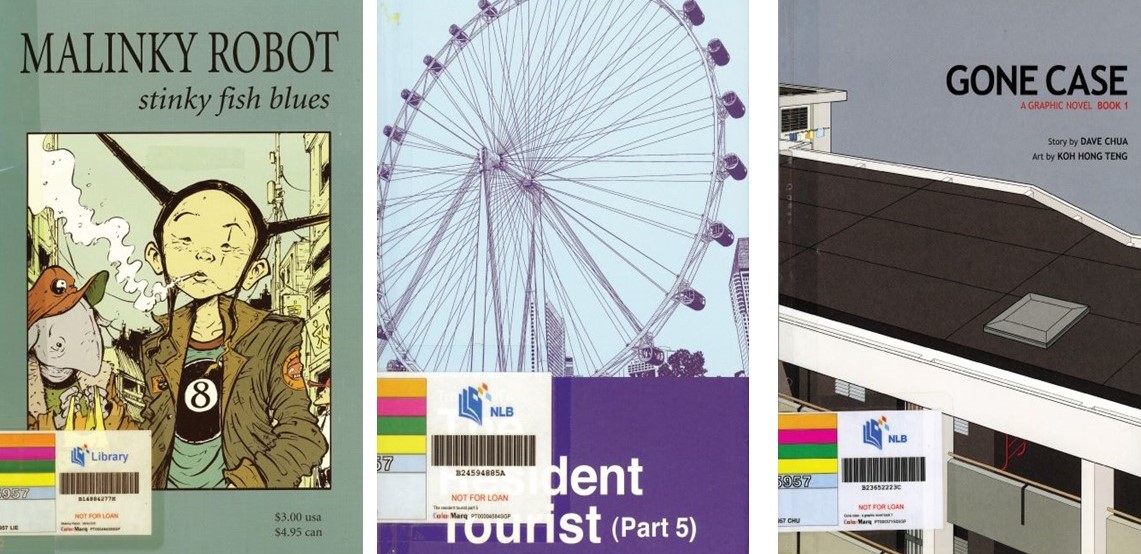

Credits from left: Red Robot Productions, 2002; Dreary Weary Comics, c. 2011; Dave Chua & Koh Hong Teng, c. 2010. All rights reserved.

Since the 1980s, the writing of Singapore’s postwar history has been dominated by the stories of Big Men and the political struggles of the 1950s and 1960s. John Drysdale’s Struggle for Success (1984) and Dennis Bloodworth’s The Tiger and the Trojan Horse (1986), were narratives of the Singapore Story produced in the 1980s, while former Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew published his memoirs in the late 1990s. The latest of such ventures was Men in White (2009).

However, there have been recent attempts to re-examine the postwar period through social and cultural lenses. Rather than being dependent on British Colonial Office records and state archival papers, works on the history of popular culture such as films (Latent Images: Films in Singapore by Jan Uhde and Yvonne Ng Uhde; Singapore Cinema by Raphael Millet) and rock music (Legends of the Golden Venus and Apache Over Singapore, both by Joseph Pereira) focus on the medium itself and they ask the question: what does a movie or a throwaway pop song tell us about ourselves and the past?[^1] Even the National Museum of Singapore in 2010 mounted an exhibition on “Singapore 1960”, using cultural artefacts and social memories to give us a sense of what lives were like back then.

Insight into the past can certainly be gained through music, movies, literature, and art. In 2006, the National Library held an exhibition commemorating the 40th anniversary of the original 1966 Six Men Woodcut Show, featuring the print works of artists Lim Yew Kuan, See Cheen Tee, Foo Chee San, Tan Tee Chie, Choo Keng Kwang and Lim Mu Hue.[^2] Looking at these prints with their depictions of street hawkers, night street scenes and the Singapore River 40 years later, one was able to glimpse the socioeconomic conditions of 1960s Singapore.

Singapore comic books and graphic novels have been around since the late 1980s. They are another primary source we can review to glean a vision of the recent past. Last year, Malaysian-born comic artist Sonny Liew was a recipient of the Young Artist Award, the first time the award was given to a comic artist. This year, local comic artist Troy Chin received the same award. This signals a turning point for the medium as it is now being taken more seriously by the state.

By looking at two comic books (one produced in the 1980s and the other in the 1990s) and the context behind their creation, we can learn a lot about these two decades.

1980s – Unfortunate Lives

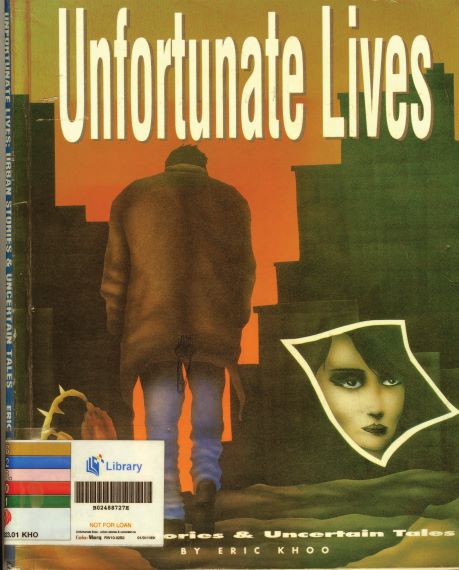

The first Singapore graphic novel comprising short stories was Eric Khoo’s Unfortunate Lives: Urban Stories, Uncertain Tales (1989), intended to be the first by the comics imprint of Times Books International.

Times Books International, c. 1989. All rights reserved.

The graphic novel was positioned as part of a cultural bloom in the arts in the late 1980s. The introduction of the book described the cultural scene as “artists, musicians, writers and producers creating works, stories, new myths about our people and our environment and lifestyle. They have been exploring the history and sociology of this young country; the tensions and conflicts of life in a new age – in ways that have never before been so visible in the public media”.

Seen in this light, Unfortunate Lives was part of the cultural spring of the mid to late 1980s. In 1986, BigO magazine organised the first alternative music gig, “No Surrender” at Anywhere, a pub in Tanglin Shopping Centre. In 1988, Kuo Pao Kun’s Mama Looking For Her Cat, Singapore’s first multilingual play, was staged.[^3] Two years later, Kuo founded The Substation.

It is now known that Khoo was inspired by the urban realism of the works of Japanese manga artist Yoshihiro Tatsumi, who is the godfather of alternative comics in Japan. Khoo faced writer’s block after being given the contract for the book Unfortunate Lives. He had to rush it out for the annual book fair in September, but the pages remained blank. After he read Tatsumi’s comics, Good-Bye and Other Stories (Catalan Communications, 1988), Khoo was so inspired by the gritty realism of Tatsumi’s works that he wrote all the stories for Unfortunate Lives in a matter of weeks. Khoo, now more well known as a film director than as a comic artist, was able to repay the debt he owed his sensei when he released his first animated feature, Tatsumi, based on the artist’s autobiographical graphic novel, A Drifting Life, as well as five of his short stories.

The nine short stories in Unfortunate Lives are bleak, drawn from the headlines of the day. “Victims of Society” retells the Adrian Lim murders of the early 1980s. “Prisoners of the Night” has a romanticised view of how young girls end up as prostitutes. The tension between art and commerce is played out in “Lost Romantics”. But the best stories are “The Canvas Environment”, “Memories of Youth”, and “State of Oppression”.[^4]

“The Canvas Environment”, a dark tale about a lonely youth, pits itself against the optimism of Singapore in the 1980s. In 1984, the country celebrated 25 years of self-government. History and academic books published then had the word “success” in their titles, such as the above-mentioned Struggle for Success and Management of Success: The Moulding of Modern Singapore, a report card on Singapore’s progress put out by the Institute of Southeast Asian Studies (ISEAS) in 1989.

In “The Canvas Environment”, a sensitive boy grows up to be a taxi driver by day and a tortured artist by night. No one understands him or his art. He shuts himself away from society and avoids the few childhood friends he has. In the end, he “escapes” into a canvas he is drawing, to be with the dream girl who exists only in his mind.

The characters Khoo favours in his stories are marginal figures, people who are downtrodden in life. He wrote on the back cover of Unfortunate Lives:

“The human personality has never ceased to fascinate me with all its complexities and charms. I am concerned about the welfare of the individual, the little man who awakens each morning to find solace in his life. These are the characters I care for and cherish… The dreamers and those who long for what they have lost.”

In Khoo’s stories, in order to survive, one either has to escape from reality into art like in “The Canvas Environment” or into the past like the protagonist of “Memories of Youth”. In the latter story, a middle-aged man is fired from his mundane job. He visits his old neighbourhood and meets his younger self and is reminded of the dreams he once had and the disappointment that his life has become.

Such bleakness begs the question: why the pessimism when things were turning around for the arts and the nation was in good shape? The answer lies in the last story of Unfortunate Lives, “State of Oppression”. One of the shortest stories in the book, it narrates, in the form of letters, the life of an old woman who has been detained without trial for 40 years in a South African country. Imprisoned for her political beliefs, she refuses to give in to the oppression of the state. In Khoo’s drawing, the character looks Chinese.

When Khoo studied at the United World College in the early 1980s, his art teacher was Teo Eng Seng, who influenced him a lot. In 1987, Teo’s sister, Teo Soh Lung, was arrested as one of the “Marxist conspirators”. Khoo wrote a story about her detention but changed the setting of the story to South Africa.[^5]

Khoo did not draw many comics after this. He went on to become an internationallycacclaimed filmmaker, with works like Mee Pok Man and Be With Me. But many of the stories he told in his films and the characters he created on screen had their origins in the hard-luck tales of Unfortunate Lives.

In his introduction to Joe Sacco’s Palestine (Fantagraphics Books, 2002), Edward Said, the late cultural critic, said: “I don’t remember when exactly I read my first comic book, but I do remember exactly how liberated and subversive I felt as a result.” Comic books have that effect and lend themselves to social criticism and satire.

1990s – Mr Kiasu

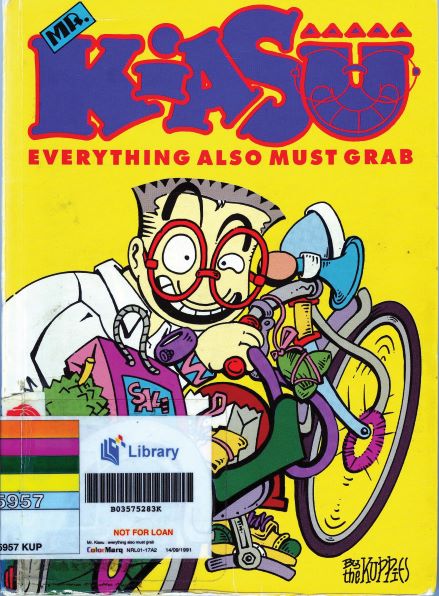

Kiasu, according to the Coxford Singlish Dictionary, is Hokkien for “afraid of losing”.[^6] Being kiasu often leads Singaporeans to behave ungraciously, such as rushing into Mass Rapid Transit (MRT) trains without waiting for other passengers to exit. Despite the fact that Singaporeans are not proud of such behaviour, it is also something good-naturedly laughed about. It took three young men who met during their national service days to bring this to national attention and allow Singaporeans to recognise this unpleasant trait in themselves.

One year after Khoo’s Unfortunate Lives premiered at the Singapore Book Fair, Johnny Lau, James Suresh and Lim Yu Cheng released the first Mr Kiasu book, “Everything I Also Want”, at the same event to great success. The first print run was 3,000 and the book sold out within weeks.[^7]

Comix Factory, 1991. All Rights Reserved.

One of the main reasons for the success of the comic was that its creators struck a chord with the 1990s zeitgeist. The early 1990s was a time when money was easily made at the stock and property markets in Singapore. The mood was one of much optimism both locally and internationally. The Berlin Wall had come down. The “evil empire” that was the Soviet Union had collapsed. The international coalition force led by the United States had successfully ended Saddam Hussein’s occupation of Kuwait. In Singapore, the economy had rebounded after the 1985 recession. Lee Kuan Yew had handed over the reins of power to Goh Chok Tong. It was a smooth transition and we were all ready for The Next Lap.

Mr Kiasu epitomised the typical Singaporean of the early 1990s. Short, stumpy and bespectacled (looking somewhat like its artist, Lim Yu Cheng), Mr Kiasu was brash, obnoxious and a die-hard bargain hunter always on the lookout for discounts, free samples and the best deals.

The character of Mr Kiasu was meant to make fun of Singaporeans’ fear of losing out and their desire to be Number One in everything. His creators were aware that mainstream publishers did not want to publish their first book because the character projected an unflattering image of Singaporeans. But the other reason why they went into self-publishing was that they feared losing control of their character.[^8] In other words, they were being kiasu themselves. The Kuppies, as Mr Kiasu’s creators called themselves, promoted this negative trait of Singaporeans and ended up being very well-off. Such a trend reflected the heady economic climate of the 1990s.

The Mr Kiasu character expanded into a brand with merchandising galore – there was a radio show, magazines, a regular strip in The Sunday Times, McDonald’s meals, a TV show, a CD and a musical. In 1993, Mr Kiasu recorded an annual turnover of $800,000 from merchandising. A year later, Kiasu Corners were set up in 7-Eleven stores islandwide.[^9] By that time, the Kuppies had signed up to 40 licences for their character.[^10]

But there was already a backlash. In 1993, The Straits Times held an essay competition for National Day and many readers wrote in to condemn kiasu behaviour. Forum letters to The Straits Times also said that McDonald’s Kiasu Burgers left a bad taste in the mouth because of the way they mocked society.[^11]

But the going remained good for the Kuppies. Up to 1998, a new Mr Kiasu book was released almost every year like clockwork. They were bestsellers, which put paid to the argument that Singaporeans hated Mr Kiasu; how could they when they were still lapping it up? The bestsellers in a country reflect its national character. We were buying and consuming ghost stories and Mr Kiasu books, which said something about what we wanted for entertainment. Mr Kiasu was a product of its time and its demise had everything to do with the times. The 1997 Asian financial crisis was a wake-up call that the good times were over. The following year, The Straits Times reported that the Mr Kiasu merchandising company had gone into debt.

The eighth and final book of the Mr Kiasu series, “Everything Also Act Blur”, was released in 1998. The death knell was heard in a parliamentary speech made by then Minister for Education Teo Chee Hean: “Let the icon of the Kiasu Singaporean fade into 20th century history, and in its place emerge the Active Singapore – the Singaporean of the 21st century.”[^12]

So how does the Mr Kiasu series read after all these years? One thing that will strike you is that Mr Kiasu is not as hateful as the media then made him out to be. He is rather likeable, if irritating. He doesn’t win all the time and his kiasu-ness often lands him in trouble. Of course, he doesn’t learn, which makes him truly a comic book character. The books score high points in their digs at the way Singaporeans behave. The second Mr Kiasu book published in 1991, “Everything Also Must Grab”, made fun of the people who refused to give up their seats to the elderly on MRT trains – the “sleeping beauty”, the “absorbed” newspaper reader and the fake old man (Mr Kiasu disguises himself as one to ensure that he need not give up his seat on the train). Today we still see such antisocial behaviour on MRT trains.

Conclusion

If Unfortunate Lives represents the artistic potential of comics to reflect real lives and social concerns, issues that also characterise more recent comics like Dave Chua and Koh Hong Teng’s Gone Case and Troy Chin’s The Resident Tourist, then Mr Kiasu highlights the commercial viability of doing comics in Singapore. This viability is further underscored by the current success of Sonny Liew, who makes a more than decent living by drawing for DC and Marvel Comics, and also that of Otto Fong and his Adventures in Science series.

Both Unfortunate Lives and Mr Kiasu present a slice of the political and social milieu of Singapore in the late 1980s and 1990s. The Singapore Memory Project, spearheaded by the National Library Board, was launched last year to capture and document the memories of Singapore and Singaporeans. Comic books are a natural medium to do just that.

The National Library Board started building its comics collection in 1999

with the opening of library@orchard on the top floor of Ngee Ann City.

The idea for starting such a collection came out of a desire to offer something

different at the new library in the heart of Orchard Road, and capturing

the youth market was a key consideration. Following the successful introduction

of comics in the library@orchard, comics collections were rolled out at

other public libraries islandwide and the genre has steadily risen in popularity

among library users.

Display of comics collection at a public library.

From 2006 to 2010, manga series such as Ranma by Rumiko Takahashi

and Zatch Bell! by Makoto Raiku, and Case Closed by Gosho

Aoyama dominated the top 30 most-read lists in the earlier years together

with a smattering of English titles such as Garfield and Hellboy.

However, in 2009 and 2010, English-language comics such as The Amazing Spider-Man, The Mighty Avengers and

game-based adaptations like World of Warcraft began appearing in

the lists of popular comics.

Besides building its print collection, the National Library Board has

also been offering comics electronically through databases such as I-Manga

and OverDrive, which are available from its eResources website (http://eresources.nlb.gov.sg).

Although library@orchard closed in 2007, comics have become a staple of

the National Library Board’s collection.

Sebastian Song, Lynn Koh, Roy See and Reena Kandoth, National Library Board

The author acknowledges with thanks the contributions of Associate Professor Ian Gordon, Department of History, National University of Singapore, in reviewing this article.

Lim Cheng Tju

Country Editor (Singapore), International Journal of Comic Art

REFERENCE

Lim, C.T. (1995). Cartoons of lives, mirrors of our times: History of political cartoons in Singapore 1959–1995. Singapore: Department of History, National University of Singapore. (Call no.: RSING q741.595957 LIM)

NOTES

[^1]: For example, see my article on the significance of Elvis Presley in Singapore in 1964. Lim, C.T. (2007, August 29). Elvis and Singapore. Citizen Historian. Retrieved from Citizen Historian website.

[^2]: Disclosure: this recreation was curated by Foo Kwee Horng, Koh Nguang How, Lai Chee Kien and me. Foo, K.H., Koh, N.H. & Lim, C.T. (2006, October). A brief history of woodcuts in Singapore. BiblioAsia, 2 (3), 30–34. Retrieved from BiblioAsia website. The original exhibition was held at the old National Library at Stamford Road in 1966. For more information, see Imprints of the past: Remembering the 1966 Woodcut Exhibition, 2006, found at the Lee Kong Chian Reference Library.

[^3]: Nureza Ahmad. (2004, May 10). First multilingual play in Singapore. Retrieved from Singapore Infopedia. In 1988, the Ong Teng Cheong Advisory Council on Art and Culture completed its extended study and recommended the setting up of the National Arts Council and the building of the Esplanade.

[^4]: In a recent exchange, Khoo said his favourite story is the “Modern Man”, a Twilight Zone-type story where an arrogant yuppie is transported to the past, chased by dinosaurs and finally eaten by cavemen who digest and shit him out. Things can’t get more literal than this.

[^5]: Teo has written about her experiences being detained without trial in Beyond The Blue Gate (2010). Lim, C.T. (2010, June 27). Unfortunate lives still [Web log comment]. Retrieved from Singapore Comix website.

[^6]: Talking cock.com (n.d.). Retrieved from Talkingcock.com website.

[^7]: Gurnani, A. (2009, September 3). In conversation with Mr Kiasu creator Johnny Lau. Retrieved from axapac website.

[^8]: Lent, J. (1995). “Mr Kiasu”, “Condom Boy” and “The House of Lim”: The world of Singapore cartoons. Journal Komunikasi, 11, 73–83.

[^9]: Zhuang, J. (2011, June 14). Mr Kiasu: Why So Like Dat? The life and times of being scared to lose. Retrieved from Justinzhuang website.

[^10]: “In conversation with Mr Kiasu creator Johnny Lau.”

[^11]: “The World of Singapore Cartoon.”

[^12]: “Mr Kiasu: Why U So Like Dat?”